The Oldest Structure on the National Mall Is on the Move

But don’t worry, it’s only going about 30 feet away

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/2f/8f2f9d51-665f-46e2-b2ac-a3b85dc5f140/photo_lockkeepers_house_cropped7_copy.jpeg)

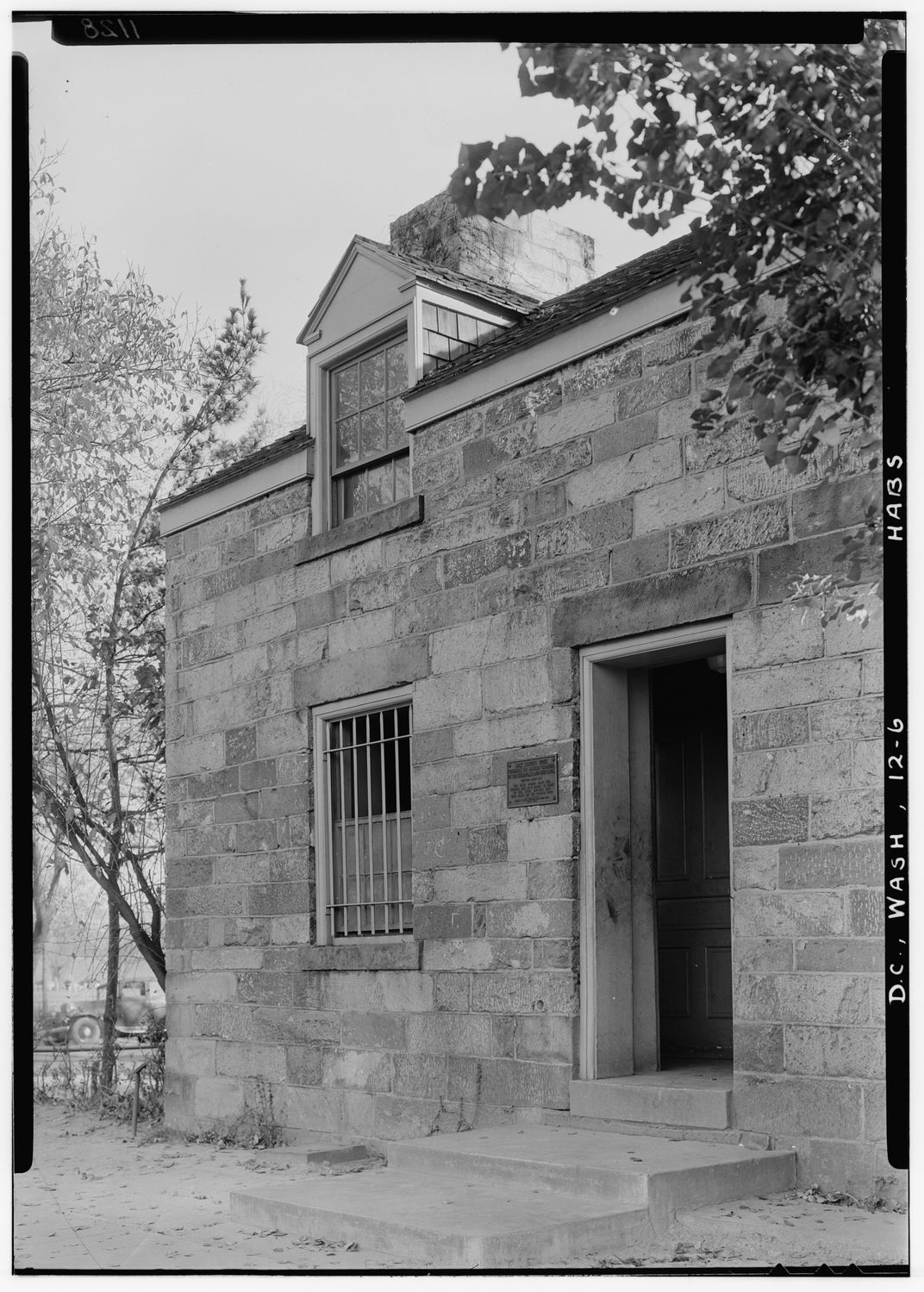

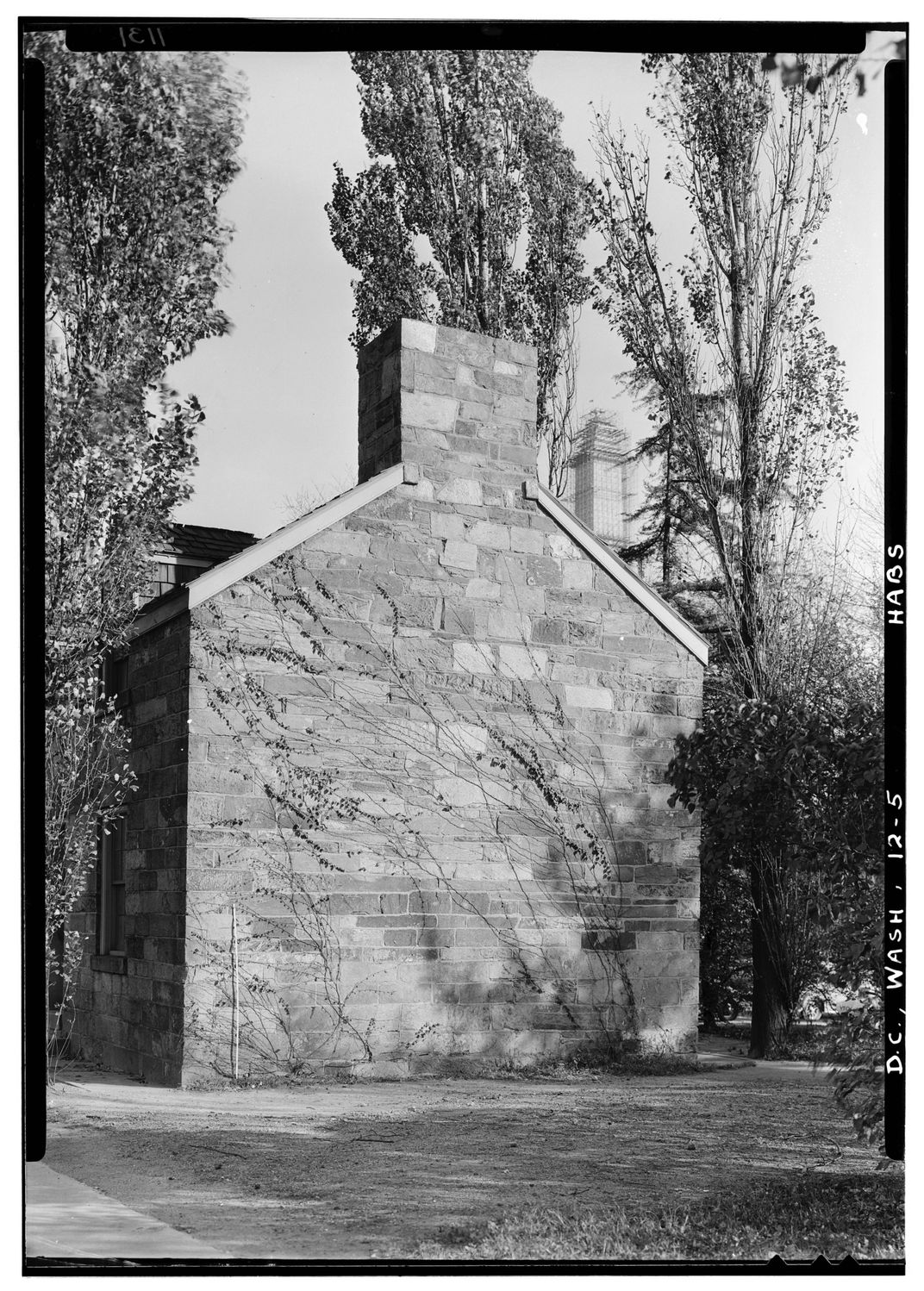

It’s easy to miss the Lockkeeper's House, a modest stone building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. With so many storied monuments and museums to visit at the heart of the nation's capital, most don't spare the 730-square-foot building on the corner of 17th and Constitution Avenue NW, a glance. But the few who do walk over and read the plaque emblazoned in front of the building learn that the small structure has lived through some of the greatest moments of American history. It is the oldest building on the Mall—and now, it's on the move.

On a blustery December day in Washington, D.C., representatives from the National Park Service and the Trust for the National Mall gathered in front of the building and dug into the damp earth. The groundbreaking symbolically ushered in a new chapter for the crumbling, 181-year-old structure that tells a fascinating story about the slow machinations of 19th-century commerce.

This isn’t the first time the Lockkeeper's House has been relocated (it was moved once before in 1915), but those in charge of the project hope that this latest move, part of an ambitious project to rehabilitate the grounds between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, will be its last.

Built around 1835, the Lockkeeper’s House was born out of the ambitions of George Washington and others who had pushed for a canal in the capital city. They believed a canal would serve as an important means of commerce by connecting the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers.

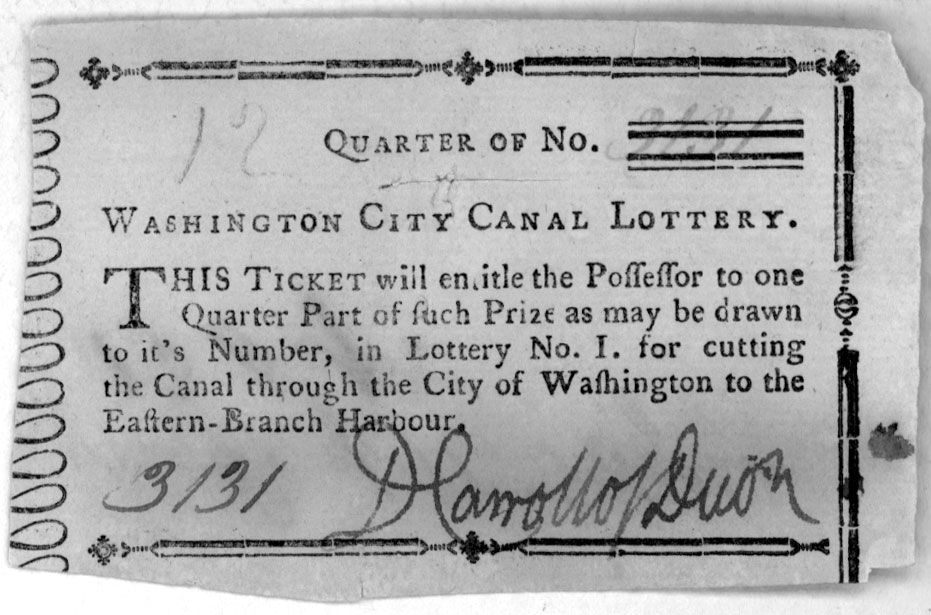

Lottery tickets were sold to raise money for the canal’s construction, but private fundraising proved dismal. Congress had to intervene multiple times to get work started, which officially broke ground in 1810 when President James Madison dug an inaugural spadeful of soggy ground.

The War of 1812 served as just one of the many delays during the Canal’s construction. In 1815, the Washington City Canal was completed, stretching 80 feet wide, and snaking from the mouth of the Goose Creek (later known as the Tiber Creek) and to the eastern branch of the Potomac (the name for the Anacostia River before the body of water was given its own independent title).

The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal would be built soon after in 1831. At first, that artificial waterway connected Georgetown—until 1871 a city of its own, separate from Washington—to Seneca, Maryland. Eventually, the C & O would go on to link up the Atlantic with the Midwest over the course of more than 180 miles. But initially, Georgetown's C & O didn't feed into the competing city canal, nor did those in charge of the C & O it have any interest in or intention to do so.

That could have been bad news for Washington City, which had taken over management of the city canal, but for the fact that the city was also an investor in the C & O. And, as J.D. Dickey writes in Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, DC, Washington had yet to pay its million dollar stock investment in the C & O. The parties reached an understanding: The money would be paid when the C & O created an extension to connect the waterways.

That extension went to what was then the wharf at 17th Street and was completed in 1833. The Lockkeeper’s House was erected at this juncture between the two canals. A lockkeeper named John Hilton was employed to live there with his wife and 13 children. He was paid an annual salary of $50 to operate the canal's lock and collect tolls, calculated in cents based on type of good, weight and length of travel.

But the city canal was quickly neglected; it festered during the Civil War and the advent of railroads changed the game for commerce. By the 1850s, excess waste had made the waterway unusable for commercial ships. The city also had no independent storm drain and sewer system, which had given the waterway an infamously putrid smell.

Washington’s dreams for the city canal would never be realized. In the 1870s, the Washington City Canal was filled in and paved over. But the Lockkeeper's House remained standing, a lasting testament to the days when Constitution Avenue was underwater.

The years haven’t been kind to the building—crumbling drywall, peeling paint and antiquated appliances don’t show off a house in its prime. But the groundbreaking on December 1 signals a new era for the house. Come June 2017, all 400,000 pounds of it will be lifted and moved on huge rollers to relieve it from some of the stress of being located so near to the traffic at the street intersection.

Davis Buckley, whose team of architects will be overseeing the project, says it's fitting that the house, which has witnessed so much history, will now be transformed into an educational space, allowing it to finally tell visitors its own story.

“It’s one of the most important contributions that could be made to the Mall in terms of having people understand what our history is,” says Buckley. “It is evocative of a time and history and place when the city first was evolving.”

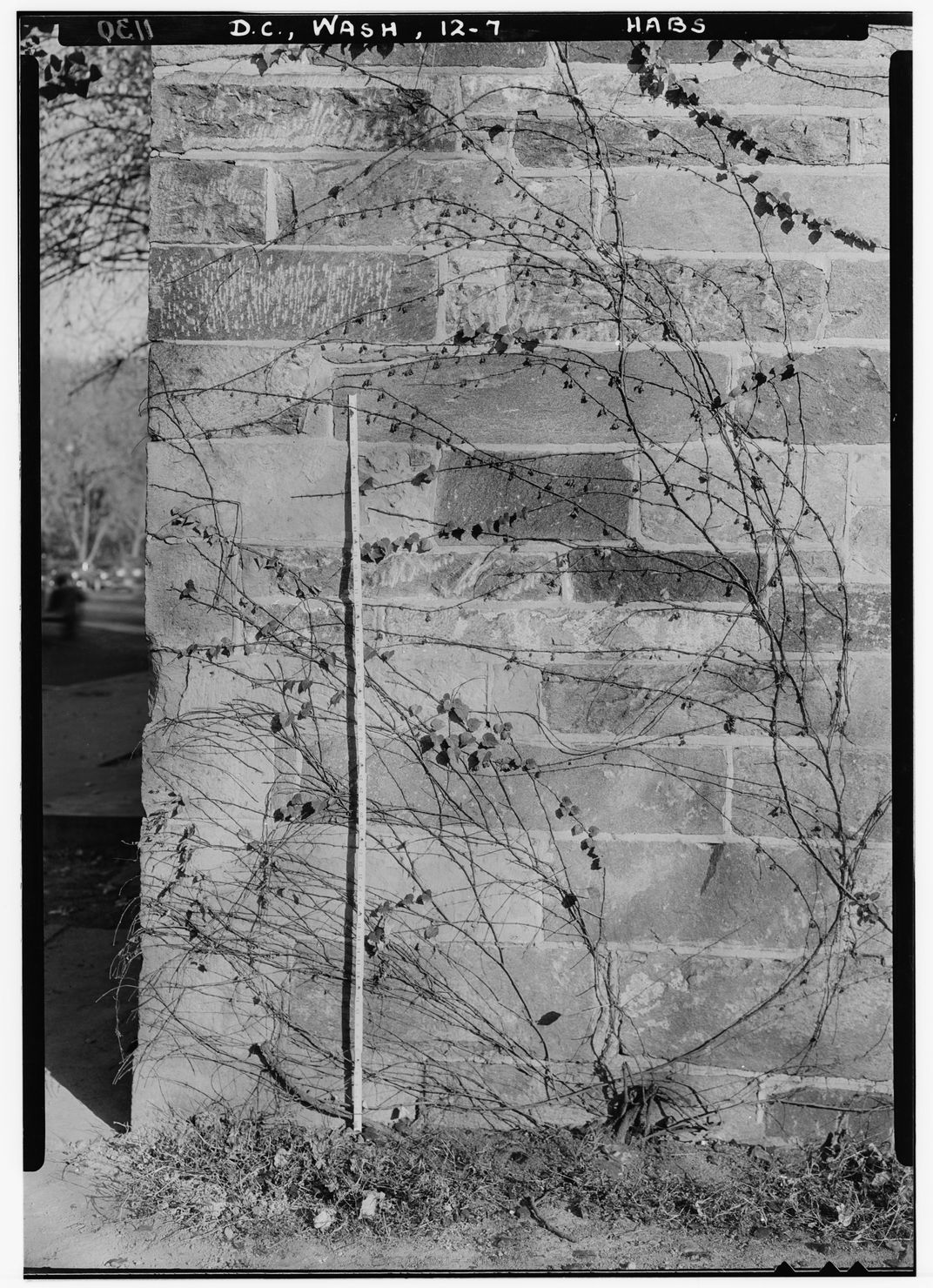

Indeed, if the walls of the small house could speak, they'd have plenty a story to tell. “John Adams used to come down here and skinny dip every morning in the Potomac River,” says Buckley, pointing toward the street. “There was a pier there, he’d go and he’d jump in.” For some time, the Historic American Buildings Survey notes, the building "served...as a squatters' tenenment, and later for the park police with a holding cell." Years after, Buckley adds, the building would witness the temporary buildings set up on the National Mall for World War II. But for the past several decades, the structure has been closed off to the public and essentially abandoned.

As part of the project, markers will be placed where the house first stood and its current location, where it's been for the past century.

The modest home’s legacy looms large. But for the time being, only its plaque (added in 1928 by the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks) tells its story. "The canal passed along the present line of B Street in front of this house emptying into Tiber Creek and the Potomac River," it reads—but when the house is restored and refitted, the world will finally learn that there’s much more to the history than that.