One Hundred Years Ago, a Lynch Mob Killed Three Men in Minnesota

The murders in Duluth offered yet another example that the North was no exception when it came to anti-black violence

:focal(754x274:755x275)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/a8/07a815af-40a5-4528-94cd-8ce5ab57264d/duluth.png)

Over the years, the horror of June 15, 1920, when three black men were lynched by a white mob in Duluth, faded away behind a “collective amnesia,” says author Michael Fedo. Faded away, at least, in the memories of Duluth’s white community.

In the 1970s, when Fedo began researching what would become The Lynchings in Duluth, the first detailed accounting of the night’s events, he met resistance from witnesses who were still alive. “All of them said, gee, why are you dredging this up again? All of them except the African American community in Duluth. It was part of their oral history, and all of those families knew of this event,” Fedo recalls.

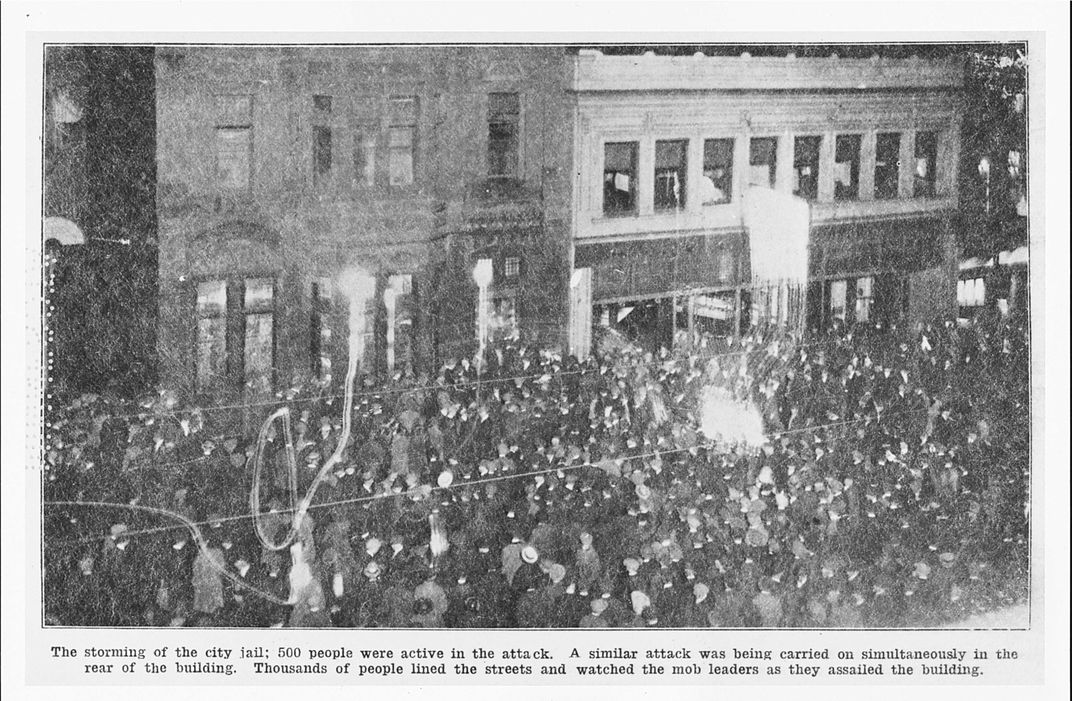

On that late spring night, 100 years ago, a crowd estimated at 5,000 people smashed their way into the Duluth police station and seized six African American men who had been arrested in connection with the alleged crime of raping a white teenager. After a mock trial in which three of them—Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie—were “convicted,” a crowd of men, women and children cheered as they were beaten and lynched, one by one. Photos of the macabre aftermath were later sold as postcards, while the national press reported on the incident with dismay.

For seven decades, their bodies remained in unmarked graves in a local cemetery until they were designated with proper markings in the early 1990s– accompanied by the words “Deterred but not Defeated.” The site of their deaths is now home to the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial, both a standing tribute to the three men and the site of ongoing educational efforts. It bears an inscription etched next friezes of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie: “An event has happened upon which it is difficult to speak and impossible to remain silent.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/04/3c04cefa-e326-4e95-8f09-a07549d42652/cjjm2.jpg)

Protesters have gathered daily at the memorial in recent weeks to protest the killing of George Floyd, another tragedy in Minnesota that elicited a nationwide reaction. On Monday night, artists gathered to paint muralsof Floyd, Breonna Taylor—who was shot in her Louisville home on March 13— and a Black Power salute.

Treasure Jenkins, a board member with the memorial, said the group wanted to provide those communities feeling anger and frustration with a “safe platform in which to express their feelings, express their frustration, and have a vision for creating a different world.”

**********

The descent into collective violence had begun just the night before, when Irene Tusken and her companion, James Sullivan, had rendezvoused at the traveling John Robinson Circus during its brief stop in Duluth. What happened behind the circus’ tents that night will never be fully known, but the pair later claimed that a group of African American laborers employed by the circus had held Sullivan at gunpoint and raped Tusken. According to newspaper reports and notes from a private investigator, however,the family physician who examined Tusken said he found no evidence of the assault, nor had Tusken mentioned to her parents that anything was amiss when she got home that night.

It was only after Sullivan had begun working his overnight shift on the docks and spoke to his father that they began making calls police, culminating in the middle-of-the-night arrests of the six men – and a handful of others who were pulled off of the circus train, already bound for the next town, and interrogated.

The next day, the 15th, a local resident named Louis Dondino drove his truck up and down Duluth’s Superior Street, inviting crowds to “join the neck-tie party,” witnesses recalled. As unverified rumors of Tusken’s rape spread, his ominous call became a bloodthirsty chorus.

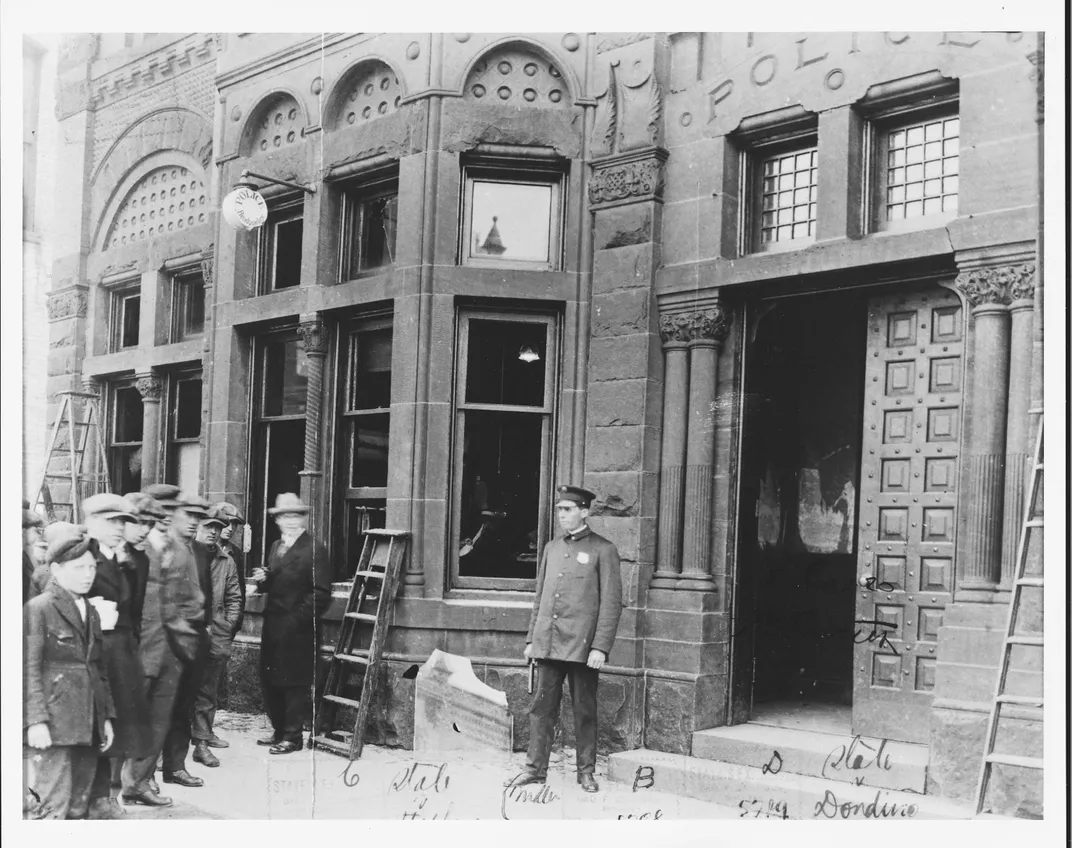

A swelling mob in the mood for vengeance descended upon the city’s police station. With the cacophony of the crowd growing louder and louder in the hours leading up to their deaths, the men trapped in their cells undoubtedly understood the horror that awaited. By approximately 9:30 p.m., the white rioters, throwing bricks and smashing in walls, overcame the undermanned police presence. Those officers left to contend with the crowd tried desperately to stave them off with a water hose, as their leadership had ordered them not to fire their weapons on the rioters.

In the final moments before the lynching, some tried to reason with the crowd. According to Fedo, two judges arrived to plead the case for the law to take its course, but to no avail. A local Catholic priest, William Powers, climbed the post himself. “In the name of God and the church I represent, I ask you to stop,” he entreated the crowd, according to a report in the National Advocate. His exhortation fell on deaf ears amid the din of rallying cries, which by then included false reports of Tusken’s death.

Duluth’s white population readily accepted the rape allegation, and were eager to condemn the African American prisoners. “It wasn’t as if [Powers] was dealing with a small group of people who were a minority in a society,” says William D. Green, professor of history at Augsburg Universityand a member of the Minnesota Historical Society’s Emeritus Council. “The mob of Duluth was made up of all classes, mothers taking their kids.”

The three victims had themselves barely reached adulthood. According to Fedo, pleas of innocence from McGhie—the first to be lynched—did nothing to dissuade the mob. Witnesses later recalled the second man, Jackson, coolly throwing a pair of dice from his pocket on the ground with the words “I won’t need these any more in this world.” Clayton was killed last, pleading for his life as he, too, was subject to merciless taunts and blows in his last moments.

After their murders, the perpetrators made no attempt to conceal their involvement, posing proudly for photographs and speaking openly with reporters at the scene. “People [were] willing and happy and crowding in, people standing on their tiptoes leaning in. They wanted to be recorded as part of this awful thing,” says Fedo.

News of the lynchings made headlines around the country. Other Minnesotans voiced a sense of disbelief that “the reproach of the South,” as theMinneapolis Journaldescribed it, could so easily happen in a northern state —placing an “ineffaceable stain on the name of Minnesota.” The gruesome killings defied their widely held sense of identity. In contrast to the violence that plagued African Americans in the South, “the North viewed itself as a separate and more superior region. It wasn’t just Minnesota, although Minnesota was right up at the top in terms a sense of exceptionalism,” says Green. Yet, when faced with increasing tensions, “the impulse to be unexceptional set in.”

Those tensions stemmed in part from resentment toward Duluth’s comparatively small African American population – comprising less than 500out of 100,000. United States Steel, a major employer in Duluth, was hiring black workers at lower wages at a time when white World War I veterans returning from Europe felt entitled to have those jobs—and with better pay.

Duluth’s issues reflected broader national turmoil. The previous year, racial violence broke out across American cities,including Chicago, where 38 people died, in what is known as the “Red Summer.” In those spasms of violence, two forces converged: the return of white veterans who needed jobs, and black veterans who hoped their service would translate to more rights, and the movement of large numbers of African Americans to northern cities, where they were often viewed as a threat to these jobs.

Alluding to violence that had gripped other Midwestern cities, including its own, the Chicago Tribuneadded its opprobrium. “Duluth has now joined the American cities which have discovered how easily the safeguards of civilized justice can be leaped,” they wrote in an editorial reprinted in Duluth’s local paper. The editorial went on to exhort the city to do better in “dealing with the men who have brought stain to [Duluth’s] good name.”

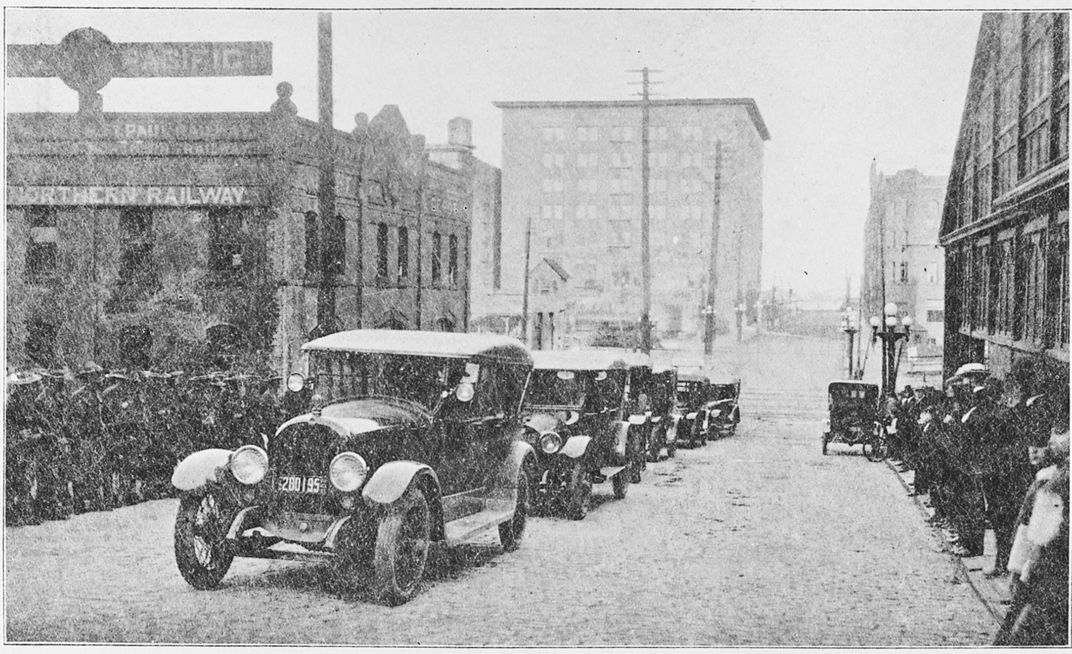

City and state levels attempted to reckon with what had happened that night. Despite a sense of unease among the city’s African American residents, activists formed a new NAACP chapter to assist in the aftermath. Governor Joseph Burnquist, himself president of the NAACP’s branch in St. Paul, commissioned an investigation by adjutant general Walter Rhinow of the Minnesota National Guard (which had been brought in to prevent further violence after the inadequate response of local law enforcement). Rhinow leveled sharp criticism at Duluth’s public safety commissioner, William Murnian, who had given the order to police not to fire their weapons out of an overriding concern for spilling the blood of white rioters.

A series of legal proceedings in the ensuing months seemingly shared the goal of expunging the unpleasant episode with symbolic convictions. Despite multiple indictments, no one was convicted of murdering McGhie, Jackson and Clayton. Three from the mob (including Louis Dondino) served relatively short sentences for rioting. Two of the African American men who had been arrested in connection with Tusken's allegations—William Miller and Max Mason—stood trial for the alleged rape. A vigorous defense, funded by the NAACP, helped secure Miller’s acquittal. Mason was convicted and sent to prison, based in part on vague physical descriptions provided by Tusken.

Despite the shock of the lynching, Mason’s conviction could at least—in the minds of the rioters—justify their actions. “I think that sort of put the local citizens’ minds at ease, if they had any ambiguity before. That was gone now because Max Mason was convicted,” says Fedo. (A request by advocates and lawyersto deliver Mason a posthumous pardonis currently under review by Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison and the Minnesota Board of Pardons.)

In the wake of the incident, prominent civil rights activist Nellie Francis championed an anti-lynching bill in the state; it passed the next spring. (Her husband, William T. Francis, had assisted in Mason’s legal defense). “The Minnesota legislature passed a law, and it was at the prompting of a black woman,” says Green.

Despite the emergence of state-level legislation (and efforts throughout the 20th century for a national law), similar legislation has yet to be codified at the federal level. Almost a century later, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act is currently stalled in the Senate.

Among those who have spoken about this tragic episode in Duluth’s history is Irene Tusken’s great-nephew, Mike Tusken, who is currently Duluth’s Chief of Police. “When you see people who are being oppressed, when you see inequities, when you see prejudice, it’s our opportunity…to stand up and to challenge that,” Tusken said at a memorial event in 2016.

While the tragedy has been thrown into stark relief in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the postponement of a large ceremony planned for the centennial anniversary of the lynching. As cities across the nation grapple with the role of racism in their own histories, organizers in Duluth are looking to next year to bring a crowd of thousands to the same street corner to symbolically match or exceed the one that gathered on June 15, 1920—this time to honor the three men whose lives were cut short on a warm spring night 100 years ago.