On July 2, 2008, a helicopter carrying more than a dozen disguised commandos landed in the jungles of southern Colombia. Masquerading as journalists and humanitarian aid workers, the military operatives set out to rescue 15 hostages held for years by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla group.

FARC members enthusiastically greeted the helicopter, mistakenly believing it had been sent to transfer the hostages—among them, a former presidential candidate, American military contractors and Colombian soldiers—to another one of the rebel group’s camps. Once in the air, the commandos disarmed FARC leader Gerardo Aguilar Ramírez (known by the nom de guerre César) and his bodyguard, who’d accompanied the captives on board. After months of covert planning, the Colombian military had successfully rescued the detainees, completing the mission in less than half an hour—without firing a gun or shedding blood.

The top-secret plan was so complex that Colombian forces dubbed it Operación Jaque, after the Spanish word for check in chess. Now, almost 14 years later, the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. is hosting a pop-up exhibition exploring the mission’s legacy. The show, which opened in May and will remain on view through the end of the year, features a collection of about 17 artifacts on loan from the Embassy of Colombia in the United States.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/74/9c/749cfaac-a26c-458e-95d6-daca08eef204/jaque_install_13.jpg)

“In and of themselves, the artifacts displayed might just look like mundane objects—a simple radio or tent,” says Alexis Albion, a special projects curator at the museum. “But when you learn about them within the context of that story, and why they had to use a specific kind of radio and why they had a specific tent, the artifacts come to life.”

Founded in 1964 as a wing of the national communist party, the FARC originally set out to overthrow the government and fight back against rampant economic inequality in Colombia. The rebels financed their operations through illegal gold mining, the drug trade, extortion and kidnapping.

Between 1990 and 2015, FARC members kidnapped or held hostage an estimated 21,396 people, according to data compiled by the Colombian Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP). Victims included politicians, soldiers, police officers, government officials and civilians, most of whom were abducted for ransom money, prisoner exchanges or territorial control in the FARC’s ongoing clash with Colombian authorities. Just last year, former FARC leaders on trial at JEP took full responsibility for the kidnappings, admitting to murdering, torturing, sexually assaulting and otherwise abusing captives. In 2016, the rebel group signed a historic peace deal with the Colombian government; it subsequently disarmed and rebranded as a political party (albeit under a different name).

The 15 hostages rescued during Operación Jaque included former Colombian presidential candidate Íngrid Betancourt; American defense contractors Marc Gonsalves, Thomas Howes and Keith Stansell; and 11 members of the Colombian police and military.

Arguably the most prominent of the captives was Betancourt, who’d been kidnapped by FARC guerrillas while campaigning for president in February 2002. On her way to the remote village of San Vicente, the politician’s car ran into a roadblock. Unsure of who was stopping her, Betancourt looked at their boots; she knew that the Colombian military wore leather army boots, while the FARC wore rubber boots.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/12/4512dba0-89f1-418e-8589-9359d1fd55b1/screen_shot_2022-06-08_at_15111_pm.png)

“When she saw that the people at the checkpoint were wearing rubber boots, she knew she was in trouble,” says Albion. “That was an interesting point for us, so we went back to the Colombian Embassy and asked whether they could give us a pair of army boots and a pair of FARC rubber boots to help make the point [in the exhibition]. And they did.”

The FARC held Betancourt hostage for six years, subjecting her to brutal treatment and unsanitary, dangerous conditions. She spent the majority of her imprisonment in camps hidden deep in the jungle.

“We discovered that the jungle was another prison,” Betancourt told NPR in 2010. “It was impossible to just get out.” Though she tried to escape multiple times, each of these attempts failed. After the politician’s third thwarted escape, the guerrillas forced her to wear a chain around her neck.

Relations among the hostages were tense, with fights breaking out over the limited communal spaces and the need for self-preservation. In a book published following their rescue, two of the three American defense contractors, who’d been kidnapped in February 2003 when their plane crashed in a FARC camp, denounced Betancourt’s behavior during their shared captivity. Betancourt, for her part, told the Guardian that the guards encouraged infighting among the prisoners, adding, “You cannot be aggressive to the guy who has a gun. But you can be aggressive to the one who’s beside [you] and is annoying you with his presence.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4c/f9/4cf90698-0d00-4de7-a172-8cb2d83fdb12/pol_-_betancourt.jpg)

The FARC regularly moved its captives around the Colombian jungle, making it difficult for would-be rescuers to track them. Though the Colombian government attempted to negotiate Betancourt’s release, the two groups failed to come to an agreement. The rebels did, however, free other prisoners over the years. Clara Rojas, who’d been kidnapped alongside Betancourt in 2002, while she was managing the politician’s presidential campaign, and former senator Consuelo González were released into the custody of a humanitarian commission in January 2008.

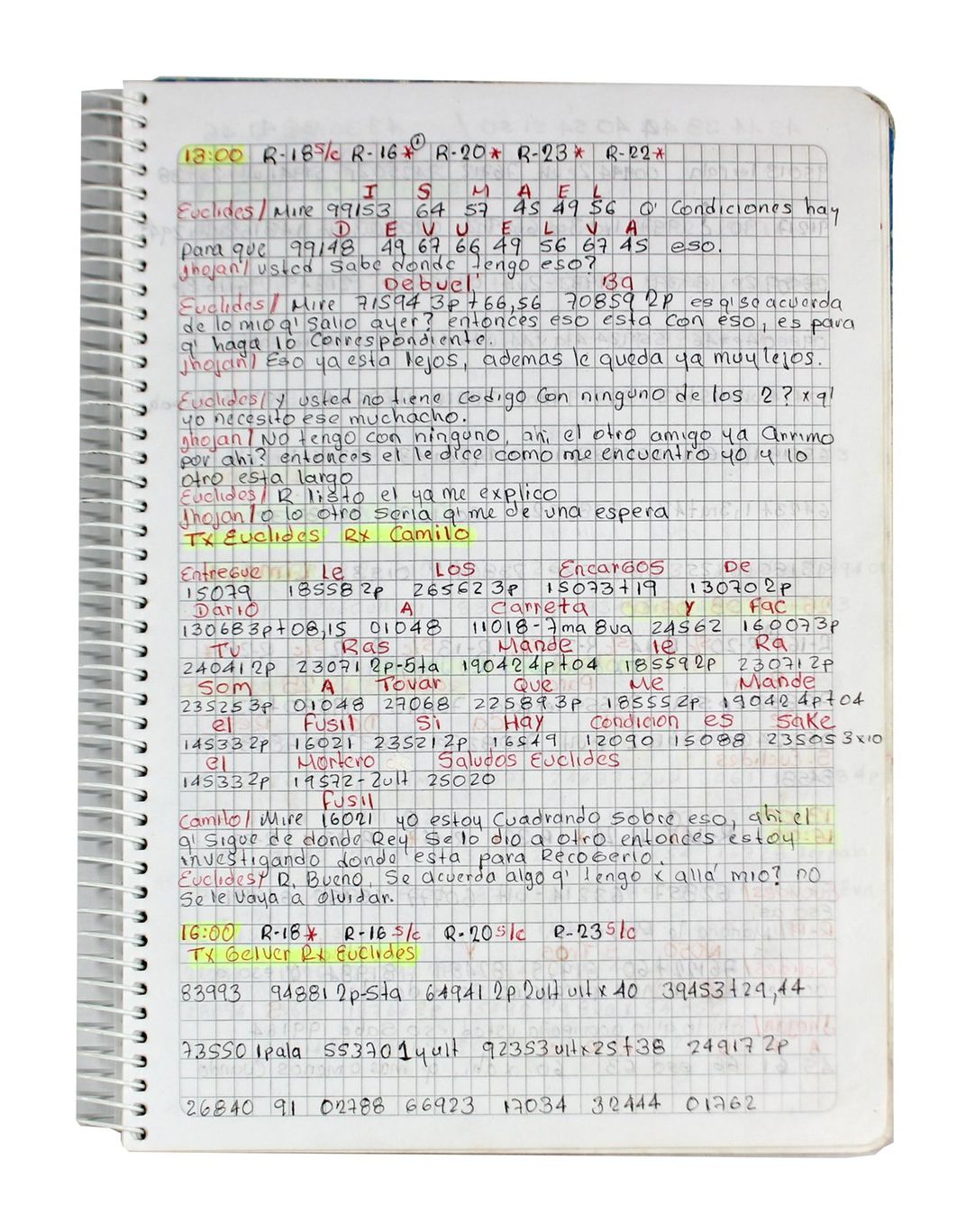

While searching for alternative ways to liberate the remaining hostages, the signals intelligence division of the Colombian military managed to break the FARC’s radio communication codes. “The signals intelligence section thought maybe, since we can interrupt their signals, we could actually pretend to be their radio communicators ourselves,” says Albion. “And they tested that out [in early 2008], and it seemed to work completely.”

Operación Jaque took shape from there. It was a twofold deception: First, the military had to trick the FARC into bringing the captives to the desired location (in this case, the Colombian department of Guaviare). Then, the commandos had to go undercover as members of a humanitarian mission tasked with transporting the prisoners to a new location.

“A few months prior to the operation, there had been a similar hostage transfer in Venezuela, ... where an international humanitarian mission had been used as a neutral party to make this transfer,” says Albion. “In the point of view of the FARC, when they saw [another proposed] humanitarian mission, it made sense, because that had already been done in Venezuela.” (Dubbed Operación Emmanuel, this January 2008 mission resulted in the release of Rojas and González.)

For the radio communications part of the operation, the Colombian military took care to mirror the technology used by the FARC, as well as the jungle conditions in which its members transmitted messages. Operators camped in the countryside while recording dispatches, making sure to include the sounds of birds and wildlife in the background.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/28/8428418e-07a9-413c-86f4-6bcf0f3dd8b5/colombian_mil_intel_agents_supplanting_farc_radio_operators_3.jpeg)

“In order to carry out a deception operation, you really have to think of all the details: having the buzz of the insects, being aware of how humanitarian mission people carry themselves differently than military commandos,” says Albion. “If anything had come across to César and his men as being a little bit off, ... the operation wouldn’t have been successful.”

The Spy Museum exhibition features a radio used by intelligence personnel, pieces of clothing worn by the undercover Colombian forces and props used to convince the FARC of the commandos’ identities. Among other items, objects on view include a T-shirt and vest emblazoned with the logo of the fake humanitarian mission and a helmet decorated with the red-and-white design associated with civilian international missions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/92/4d/924d3add-f043-4df7-9724-01b7d3ccbe73/vest.jpg)

As Albion points out, the undercover operatives had to not only look the part but also act it. To ensure believability, they even took acting lessons.

On the day of the rescue, everything went according to plan. “They closed the helicopter doors, the helicopter started flying and suddenly there was something happening,” Betancourt told CNN shortly after her return home. “... I saw the commander who, during four years, had been at the head of our team, who so many times was so cruel and humiliated me, and I saw him on the floor naked with bound eyes.”

Finally free, Betancourt and the other hostages “started jumping, we screamed, we cried, we hugged. We couldn’t believe it.”

At the time of Operación Jaque, Juan Carlos Pinzón, the Colombian ambassador to the U.S., was the Colombian vice minister of defense. He cites the mission as a key example of successful collaboration between the two countries, which are currently marking 200 years of diplomatic relations.

“This operation is comparable to the Trojan Horse, so it has always been a source of pride because it was a perfect job between the Colombian military, ... which planned and executed the operation, [and] the United States,” says Pinzón in an interview translated from Spanish by Smithsonian magazine. “This exhibition will enable us to tell all the things that we have done together through an operation with special historical and strategic connotations.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/08/41/0841cca3-04cb-42a1-a7a0-98863d2e5a88/2d1kyhg_1.jpg)

Though Colombians actually carried out Operación Jaque, support from the U.S. played a key role in the mission’s success. As the New York Times reported in July 2008, hundreds of U.S. military personnel helped search for the hostages, including the three American defense contractors kidnapped in 2003. The U.S. also offered Colombia financial aid, military intelligence advice and technological support.

Pinzón deems the Spy Museum exhibition’s opening timely, as it coincides with the 200th anniversary of Colombia-U.S. relations. Colombia is the first Latin American nation to celebrate an alliance of such length with the U.S.; in 1822, the U.S. House of Representatives formally recognized Colombia’s independence from Spain and allocated funds to start diplomatic relations. In recent decades, the U.S. has funded such initiatives as Plan Colombia, which addressed drug trafficking and ongoing unrest in the country, and Peace Colombia, which supported peace negotiations with the FARC following the signing of a 2016 peace accord.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/90/6790b1e4-409e-4473-b0ef-1b9258dfb961/disguise_2.jpg)

Operación Jaque continues to resonate more than a decade after its successful execution. “This is a story from not that long ago, [and] some of its elements are still around,” says Albion. Betancourt, for instance, just ended her second bid for the Colombian presidency last month.

Pinzón hopes that museum visitors will learn about Colombia’s history through a Colombian lens. “It’s very important to recognize the heroes that are still alive, as we usually recognize people who have already passed away,” he says. “Here, we will celebrate the flesh-and-blood heroes who are still among us, who risked their lives, went into the wolf’s mouth, and managed to rescue, without firing a single shot, people who had been kidnapped for ... years and whose human rights, dignity and integrity had been totally violated by a terrorist organization that was financed by drug trafficking.”

“Operación Jaque” is on view at the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. through December 31, 2022.

:focal(1752x1168:1753x1169)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/16/22/1622ed89-4601-4a18-8884-36d8bb7b62c1/ap_080702024631.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anto.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anto.png)