Editor's Note, August 23, 2023: In 2013, Smithsonian magazine commissioned this oral history of the 1963 March on Washington to mark the 50th anniversary of the seminal event. In the decade since, a number of participants, including Representative John Lewis, Harry Belafonte, Juanita Abernathy and Julian Bond have died, leaving interviews such as these as remembrances of their courage and fortitude

This year, ahead of the 60th anniversary of the march, recall the moments that led to the civil rights milestone and what the gathering meant to those who were there.

Ken Howard, a D.C. student working a summer job at the post office before entering Howard University in the fall, took a bus downtown to join a massive gathering on the National Mall. “The crowd was just enormous,” he recalls. “Kind of like the feeling you get when a thunderstorm is coming and you know it is going to really happen. There was an expectation and excitement that this march finally would make a difference.”

Only a few months before, in that electric atmosphere of anticipation, 32-year-old singer-songwriter Sam Cooke composed “A Change Is Gonna Come,” the song that would become the anthem of the civil rights movement.

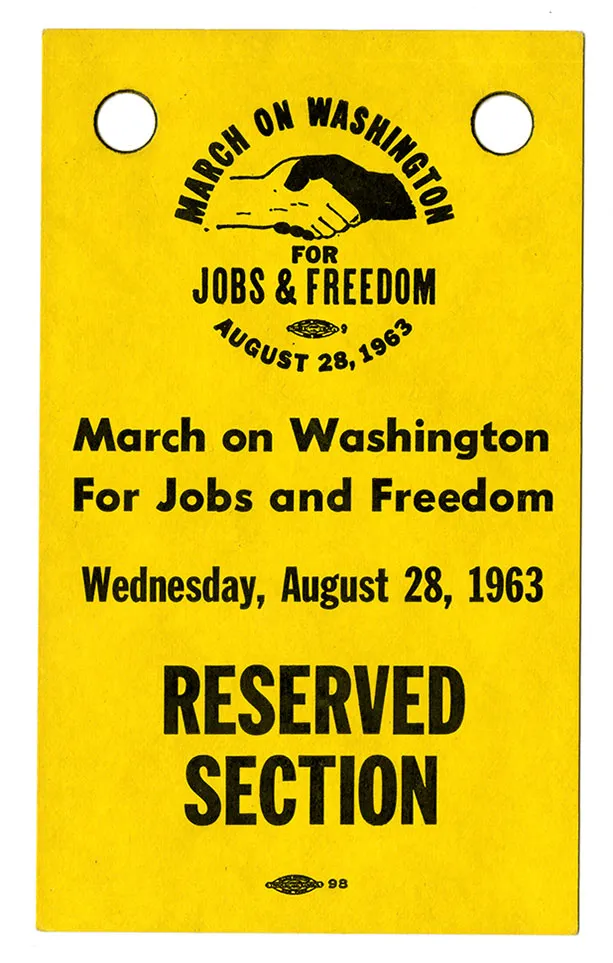

The potent symbolism of a demonstration at the Lincoln Memorial—timed to coincide with the centenary of the Emancipation Proclamation and following President John F. Kennedy’s announcement in June that he would submit a civil rights bill to Congress—transfixed the nation. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom also catapulted 34-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., who set aside prepared notes to declare “I Have a Dream,” into the realm of transcendent American orators.

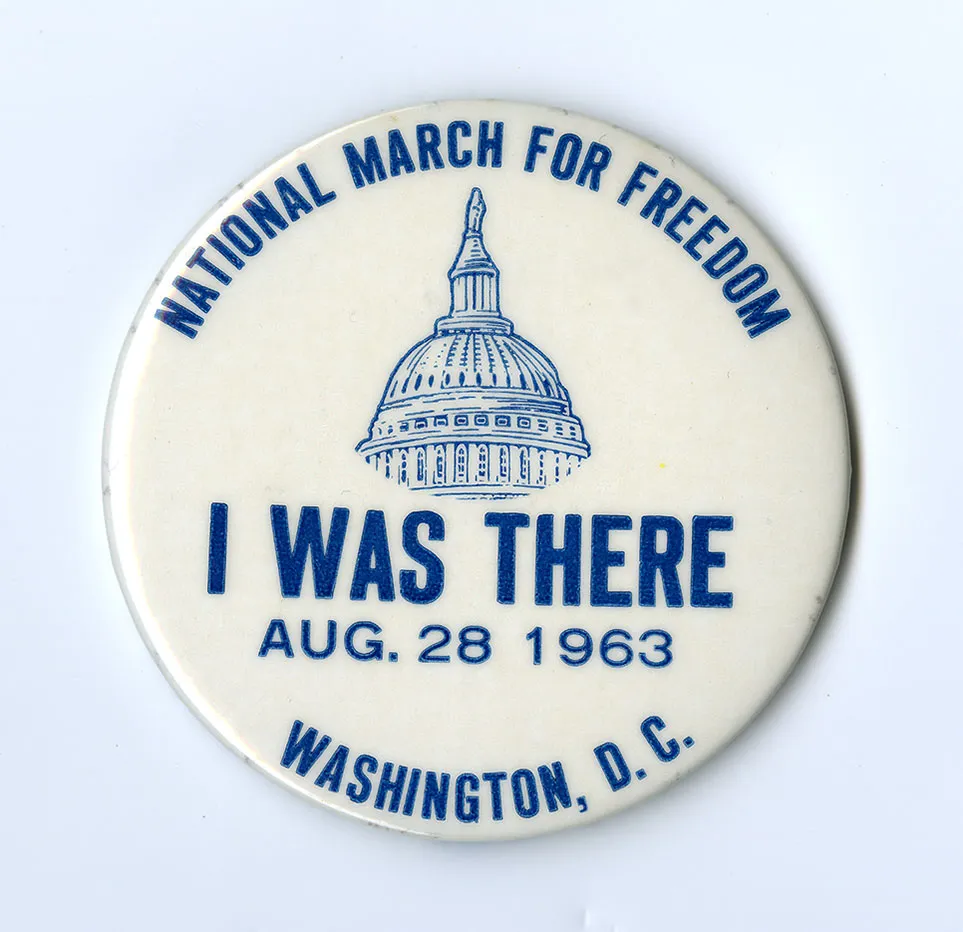

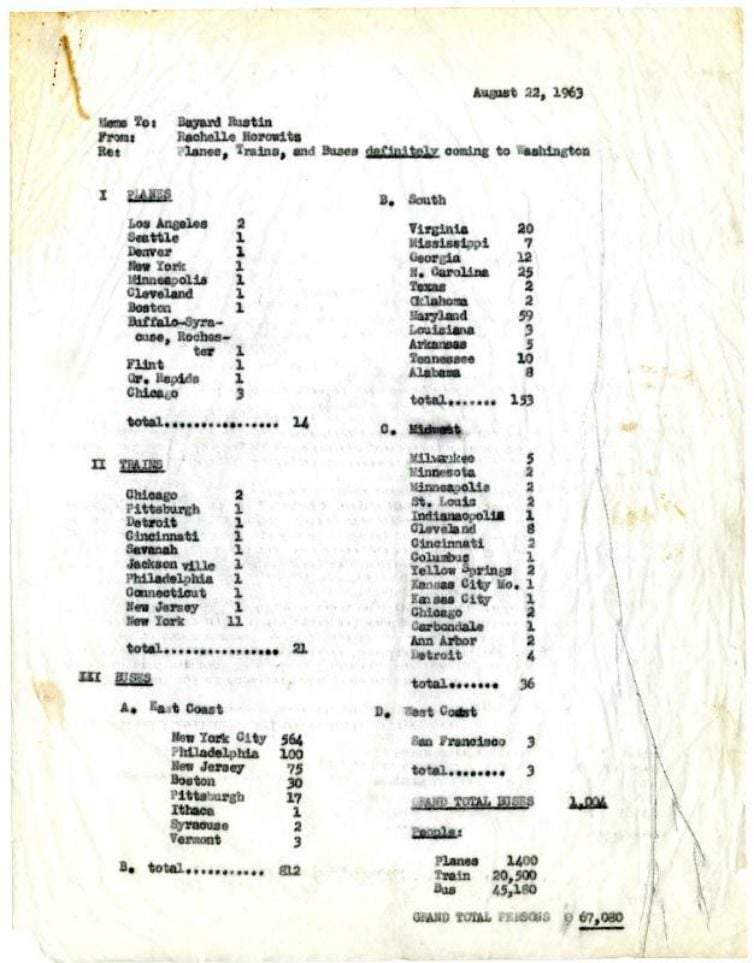

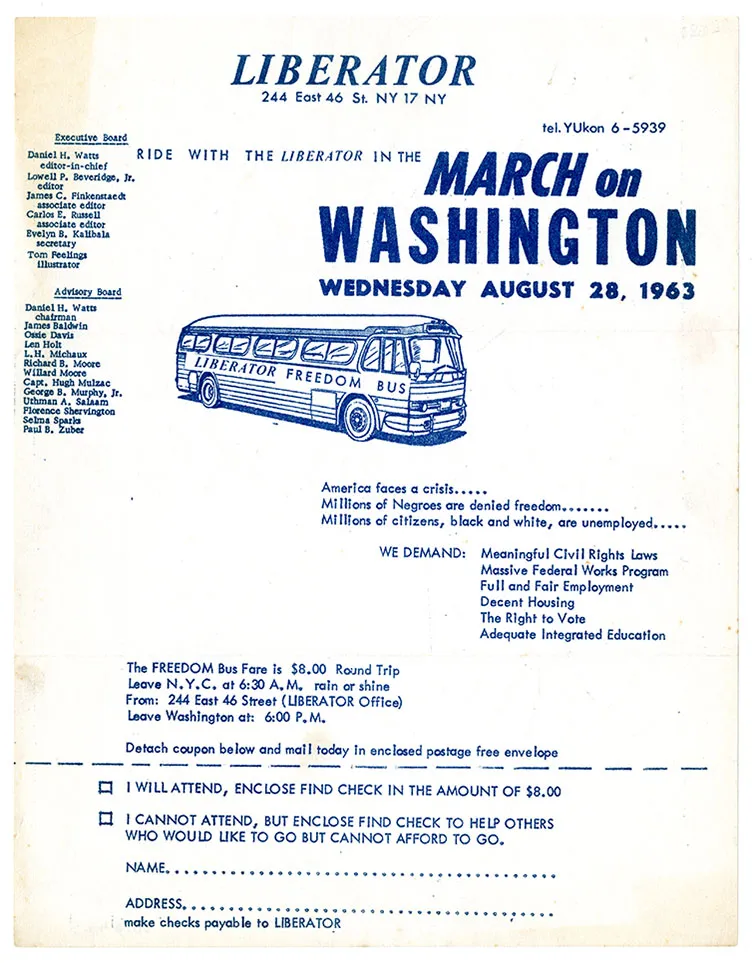

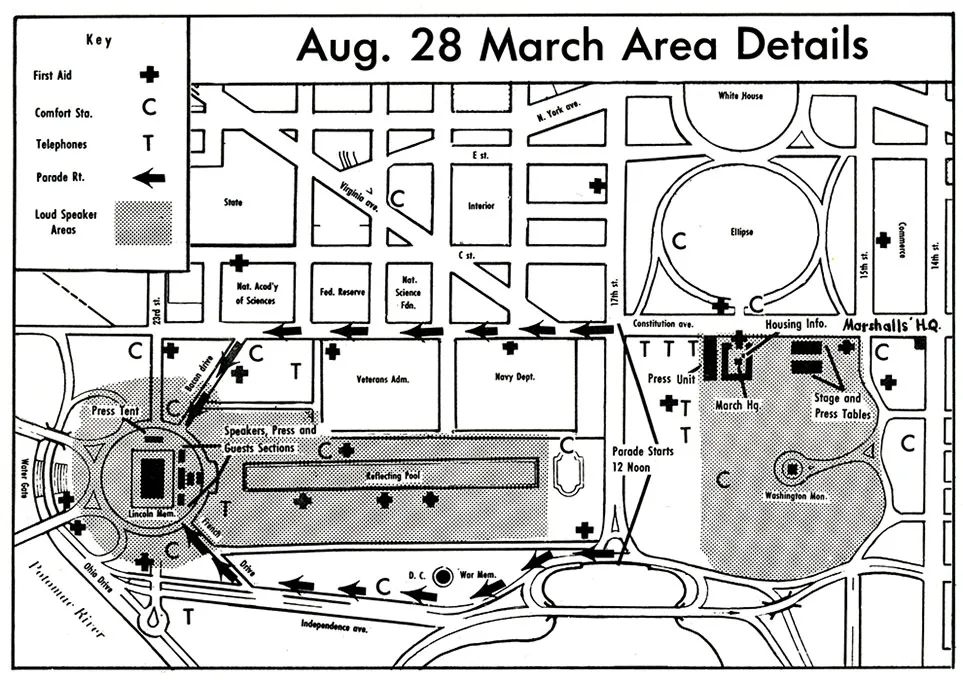

Behind the scenes, the lead organizer, Bayard Rustin, presided over a logistical campaign unprecedented in American activism. Volunteers prepared 80,000 50-cent boxed lunches (consisting of a cheese sandwich, a slice of poundcake and an apple). Rustin marshaled more than 2,200 chartered buses, 40 special trains, 22 first-aid stations, eight 2,500-gallon water-storage tank trucks and 21 portable water fountains.

Participants traveled from across the country—young and old, Black and white, celebrities and ordinary citizens. Everyone who converged on the capital that day, whether or not they recognized their accomplishment at the time, stood at a crossroads from which there would be no turning back. Fifty years later, some of those participants—including John Lewis, Julian Bond, Harry Belafonte, Eleanor Holmes Norton and Andrew Young—relived the march in interviews recorded during the past several months in Washington, D.C., New York and Atlanta. Taken together, their voices, from a coalition including the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), assume the force of collective memory.

A 42-year-old photographer, Stanley Tretick, who covered the Kennedy White House for Look magazine, was on the Mall as well. He documented the transformative moment in images unpublished until now, restored to history in Kitty Kelley’s Let Freedom Ring, a posthumous collection of Tretick’s work from that day. View more of Tretick's stunning photographs here.

The demonstrators who sweltered in the 83-degree heat as they petitioned their government for change—the crowd of at least 250,000 constituted the largest gathering of its kind in Washington—remind us of who we were then as a nation, and where we would move in the struggle to overcome our history. “It’s difficult for someone these days,” says Howard, “to understand what it was like, to suddenly have a ray of light in the dark. That’s really what it was like.”

Table of Contents

1. Planning the March on Washington

2. The morning of the March on Washington

Planning the March on Washington

Ken Howard: You have to back up and think about what was happening at the time. Nationally, in 1962, you have James Meredith, the first Black to attend the University of Mississippi, that was national news. In May 1963, Bull Connor with the dogs and the fire hoses, turning them on people, front-page news. And then in June, that summer, you have Medgar Evers shot down in the South, and his body actually on view on 14th Street at a church in D.C. So you had a group of individuals who had been not just oppressed, but discriminated against and killed because of their color. The March on Washington symbolized a rising up, if you will, of people who were saying enough is enough.

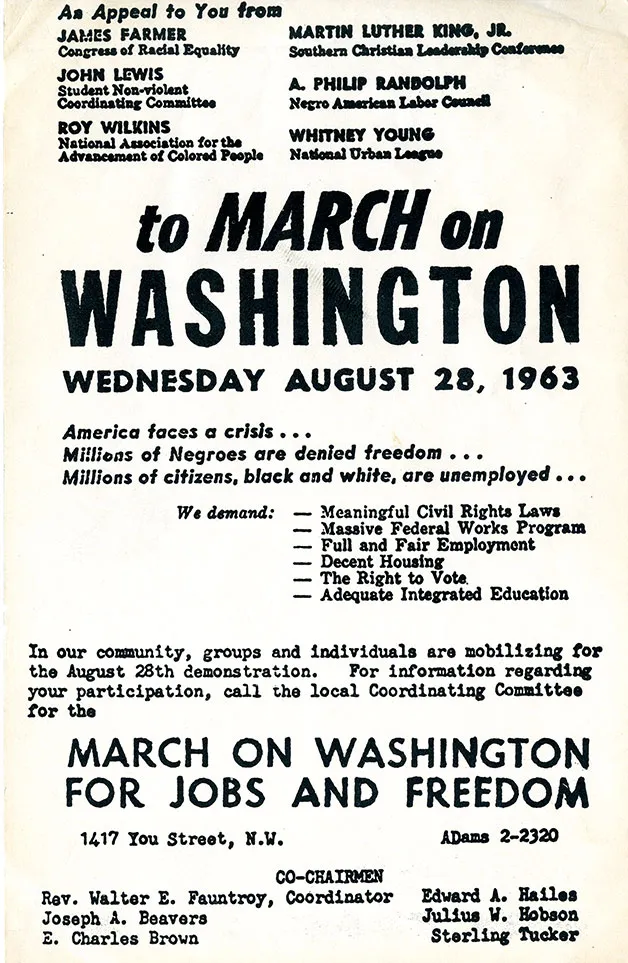

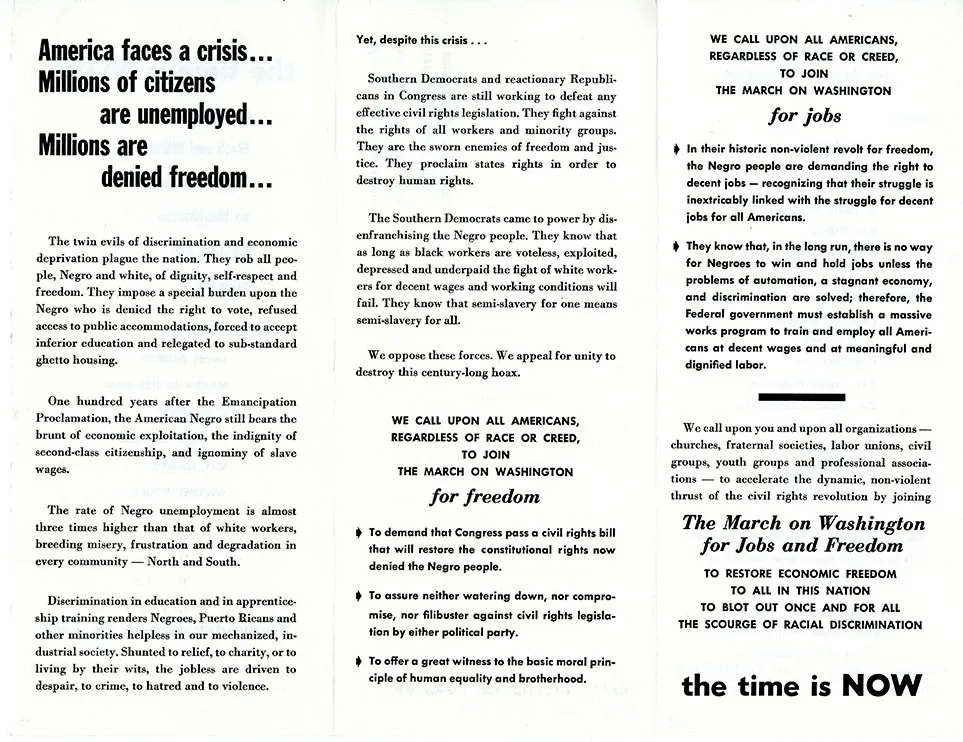

Rachelle Horowitz, aide to Bayard Rustin (later a labor union official): A. Philip Randolph [president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters] had tried to put on a march in 1941 to protest discrimination in the armed forces and for a fair employment policy commission. He called off that march when FDR issued an executive order [prohibiting discrimination in the national defense industry]. But Randolph always believed that you had to move the civil rights struggle to Washington, to the center of power. In January 1963, Bayard Rustin sent a memo to A. Philip Randolph in essence saying the time is now to really conceive of a big march. Originally it was conceived of as a march for jobs, but as ’63 progressed, with the Birmingham demonstrations, the assassination of Medgar Evers and the introduction of the Civil Rights Act by President Kennedy, it became clear that it had to be a march for jobs and freedom.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, SNCC activist (later a 12-term D.C. delegate to Congress): I was in law school, I was in Mississippi in the delta working on the predecessor for the workshops that were to take place a year later in the Freedom Summer. I got a call from one of my friends in New York who said, “You need to be here, Eleanor, because we are developing the March on Washington.” So I spent part of the summer in New York, working on this truly fledgling March on Washington. Bayard Rustin organized it out of a brownstone in Harlem; that was our office.

When I look back now, I am all the more impressed with the genius of Bayard Rustin. I do not believe that there was another person involved with the movement who could have organized that march—the quintessential organizer and strategist. Bayard Rustin was maybe the only openly gay man I knew. That was simply “not respectable,” so he was attacked by Strom Thurmond and the Southern Democrats, who sought to get at the march by attacking Rustin. To the credit of the civil rights leadership, they closed in around Rustin.

“We’re going to walk together. We’re going to stand together. We’re going to sing together. We’re going to stay together.” -The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth (Radio transcript excerpts, in block quotes, courtesy of WGBH Media Library and Archives)

John Lewis, chairman of SNCC (later a 13-term congressman from Georgia): A. Philip Randolph had this idea in the back of his mind for many years. When he had his chance to make another demand for a March on Washington, he told President Kennedy in a meeting at the White House in June 1963 that we were going to march on Washington. It was the so-called “Big Six,” Randolph, James Farmer, Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King Jr. and myself.

Out of the blue, Mr. Randolph spoke up. He was the dean of Black leadership, the spokesperson. He said, “Mr. President, the Black masses are restless, and we are going to march on Washington.” President Kennedy didn’t like the idea, hearing people talk about a march on Washington. He said, “If you bring all these people to Washington, won’t there be violence and chaos and disorder and we will never get a civil rights bill through the Congress?” Mr. Randolph responded, “Mr. President, this will be an orderly, peaceful, nonviolent protest.”

“The March on Washington is not the climax of our struggle, but a new beginning not only for the Negro but for all Americans who thirst for freedom and a better life. When we leave, it will be to carry on the civil rights revolution home with us into every nook and cranny of the land, and we shall return again and again to Washington in ever growing numbers, until total freedom is ours.” -A. Philip Randolph

Harry Belafonte, activist and entertainer: We had to seize this opportunity and make our voices heard. Make those who are comfortable with our oppression—make them uncomfortable—Dr. King said that was the purpose of this mission.

Andrew Young, aide to King at the SCLC (later a diplomat and human rights activist): Dr. Randolph’s march basically was an attempt to transform a Black Southern civil rights movement into a national movement for human rights, for jobs and freedom. And anti-segregation. So it had a much broader base—the plan was to include not only SCLC but all of the civil rights organizations, the trade union movement, the universities, the churches—we had a big contingent from Hollywood.

Julian Bond, communications director, SNCC (later a University of Virginia historian): I thought it was a great idea, but within the organization, SNCC, it was thought to be a distraction from our main work, organizing people in the rural South. But John [Lewis] had committed us to it, and we would go with our leadership and we did.

Joyce Ladner, SNCC activist (later a sociologist): At that point, the police all over Mississippi had cracked down so hard on us that it was more and more difficult to raise bond money, to organize without harassment from the local cops and the racists. I thought a large march would demonstrate that we had support outside our small group.

Horowitz: As we started planning the march, we started getting letters from our dear friends in the Senate of the United States, people who were advocates of civil rights. Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois, Phil Hart of Michigan, Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. The letters began either “Dear Mr. Randolph” or “Dear Bayard: We think that it’s very important to pass the civil rights bill and we believe very strongly in what you are doing, but have you considered the difficulty of bringing in 100,000 people in Washington? Where will they use the bathrooms? Where will they get water?”

Every letter was identical. Bayard began to refer to them as “latrine letters,” and we put latrine letters on the side. They were inspirational in one way, in that Bayard arranged to rent scores of portable johns. We found out later that Senator Paul Douglas’ son, John Douglas, was working in the Justice Department. He and a guy named John Reilly were writing these letters and giving them to the senators to send to us. Before robo-type, there were these letters.

Belafonte: To mobilize the cultural force behind the cause—Dr. King saw that as hugely strategic. We use celebrity to the advantage of everything. Why not to the advantage of those who need to be liberated? My job was to convince the icons in the arts that they needed to have a presence in Washington on that day. Those that wanted to sit on the platform could do that, but we should be in among the citizens—the ordinary citizens—of the day. Somebody should just turn around and there was Paul Newman.

Or turn around and there was Burt Lancaster. I went first to one of my closest friends, Marlon Brando, and asked if he would be willing to chair the leading delegation from California. And he said yes. Not only enthusiastically but committed himself to really working and calling friends.

“I’m speaking at the moment with Mr. Percy Lee Atkins of Clarksdale, Mississippi: ‘I came because we want our freedom. What’s it going to take to have our freedom?’” -Radio reporter Al Hulsen

Juanita Abernathy, widow of SCLC co-founder the Reverend Ralph Abernathy (later a corporate executive): We were there [in Washington] two days prior. We flew up [from Atlanta]. They expected us to be violent and for Washington to be torn up. But everybody had been told to remain nonviolent, just as we had been throughout the movement.

Lewis: I started working on my speech several days before the March on Washington. We tried to come up with a speech that would represent the young people: the foot soldiers, people on the front lines. Some people call us the “shock troops” into the delta of Mississippi, into Alabama, southwest Georgia, eastern Arkansas, the people who had been arrested, jailed and beaten. Not only our own staffers but also the people that we were working with. They needed someone to speak for them.

The night before the march, Bayard Rustin put a note under my door and said, “John, you should come downstairs. There’s some discussion about your speech, some people have a problem with your speech.”

The archbishop [of Washington, D.C.] had threatened not to give the invocation if I kept some words and phrases in the speech.

In the original speech, I said something like “In good conscience, we cannot support the administration’s proposed civil rights bill. It was too little, too late. It did not protect old women and young children in nonviolent protests run down by policemen on horseback and police dogs.”

Much farther down, I said something like “If we do not see meaningful progress here today, the day will come when we will not confine our marching on Washington, but we may be forced to march through the South the way General Sherman did, nonviolently.” They said, “Oh no, you can’t say that; it’s too inflammatory.” I think that was the concern of the people in the Kennedy administration. We didn’t delete that portion of the speech. We did not until we arrived at the Lincoln Memorial.

Ladner: The day before the march, my sister and Bobby Dylan, who was her good friend, went to a fundraiser that night. She met Sidney Poitier; he was very, very involved with SNCC, as was Harry Belafonte. The next morning, we picketed the Justice Department because three of our SNCC workers were in jail in Americus, Georgia, for sedition, “overthrowing the government.” If you can imagine, people who were 18, 19, 20 years old, close friends, who were arrested for overthrowing the government, the state? They had not been able to get bond. We were terrified that they would in fact be charged and sent up for a long time. So we picketed in an effort to draw attention to their plight.

The morning of the March on Washington

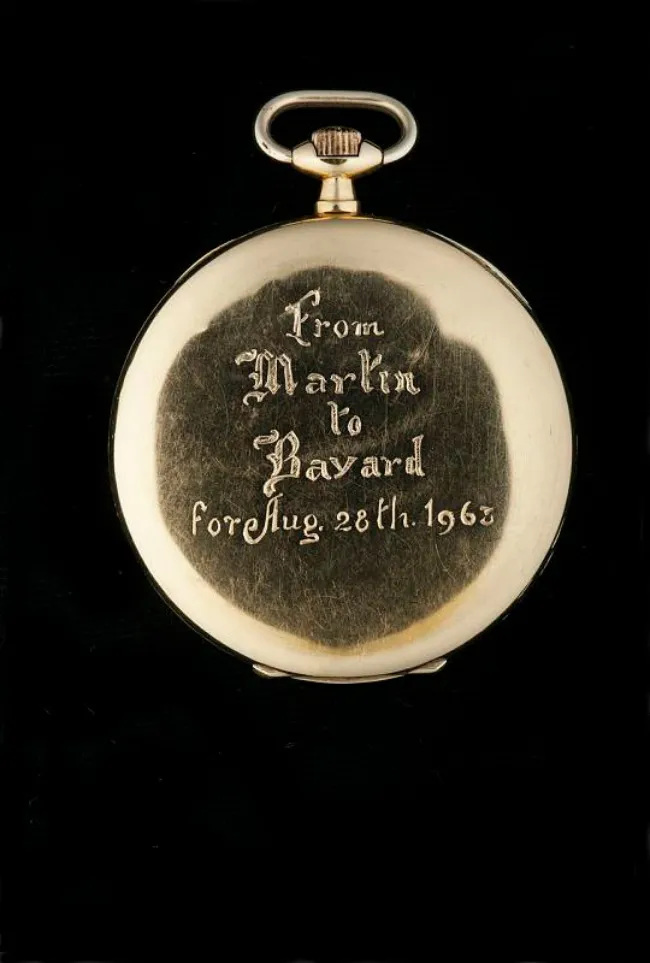

Horowitz: It was about 5:30 in the morning, it’s gray, it’s muggy, people are setting up. There’s nobody there for the march except some reporters, and they start annoying Bayard and pestering him: “Where are the people, where are the people?” Bayard very elegantly took a piece of paper out of his pocket and looked at it. Took out a pocket watch that he used, looked at both and said, “It’s all coming according to schedule,” and he put it away. The reporters went away and I asked, “What were you looking at?” He said, “A blank piece of paper.” Sure enough, eventually, about 8:30 or 9, the trains were pulling in and people were coming up singing and the buses came. There’s always that moment of “We know the buses are chartered, but will they really come?”

“At 7 o’clock, the first ten people were here. They brought their own folding chairs and are to my left down near the Reflecting Pool. The Reflecting Pool early this morning is very calm and so gives a nice reflection of the Washington Monument. There are apparently fish or some sort of fly in the Reflecting Pool because every few minutes you see little wavelets in the middle.” -Radio reporter David Eckelston

Courtland Cox, SNCC activist (later civil servant and businessman): Bayard and I left together. It was real early, maybe 6 or 7 in the morning. We went out to the Mall and there was literally no one there. Nobody there. Bayard looks at me and says, “You think anybody is coming to this?” and just as he says that, a group of young people from an NAACP chapter came over the horizon. From that time, the flow was steady. We found out that we couldn’t see anyone there because so many people were in buses, in trains and, particularly, on the roads, that the roads were clogged. Once the flow started, it was just volumes of people coming.

“All sorts of dress is evident, from the Ivy League suit to overalls and straw hats and even some Texas ten-gallon hats. Quite a few people are carrying knapsacks, blankets and so on, apparently anticipating a not-too-comfortable trip home tonight." -Radio reporter Al Hulsen

Barry Rosenberg, civil rights activist (later a psychotherapist): I could hardly sleep the night before the march. I got there early. Maybe 10:30 in the morning, people were milling around. There were maybe 20,000 folks out there. It was August; I forgot to wear a hat. I was a little concerned about getting burned up. I went and got a Coke. When I got back, people just poured in from all directions. If you were facing the podium, I was on the right-hand side. People were greeting each other; I got chills, I got choked up. People were hugging and shaking hands and asking, “Where are you from?”

“One woman from San Diego, California, showed us her plane ticket. She said her grandfather sold slaves and she was here ‘to help wipe out evil.’” -Radio reporter Arnold Shaw

Lewis: Early that morning, the ten of us [the Big Six plus four other march leaders] boarded cars that brought us to Capitol Hill. We visited the leadership of the House and the Senate, both Democrats and Republicans. In addition, we met on the House side with the chairman of the judiciary committee, the ranking member, because that’s where the civil rights legislation will come. We did the same thing on the Senate side. We left Capitol Hill, walked down Constitution Avenue.

Looking toward Union Station, we saw a sea of humanity: hundreds, thousands of people. We thought we might get 75,000 people showing up on August 28. When we saw this unbelievable crowd coming out of Union Station, we knew it was going to be more than 75,000. People were already marching. It was like, “There go my people. Let me catch up with them.” We said, “What are we going to do? The people are already marching! There go my people. Let me catch up with them.” What we did, the ten of us, was grab each other’s arms, made a line across the sea of marchers. People literally pushed us, carried us all the way, until we reached the Washington Monument and then we walked on to the Lincoln Memorial.

Ladner: I had a stage pass, so I could get on the podium. Just standing up there looking out at not very many people, then just all of the sudden, hordes of people started coming. I saw a group of people with large banners. Philadelphia NAACP could have been one section, for example, and they did come in large groups. As the day passed, a lot of individual people were there. Odetta and Joan Baez and Bobby Dylan. They began warming up the crowd very early, began singing. It was not tense at all, wasn’t a picnic either. Somewhere in between; people were happy to see each other, renewing acquaintances, everyone was very pleasant.

“Many people [are] sitting, picnicking along the Reflecting Pool steps below the monument. People with headbands, arm bands, buttons all around, but in a happy holiday atmosphere.” -Radio reporter Arnold Shaw

The March on Washington

Howard: [I was] at the post office that summer. I’d been working all day. I got on the bus [to downtown]. I was hot, sweaty, but I was determined that I was going to the march. The crowd was enormous. There were rumors, apparently substantiated, that agents of the government, intelligence agents, were actually taking pictures. Some of those individuals took pictures of me. More power to them. I had nothing to fear. I was at least in partial uniform with my postal hat [pith helmet] and shirt on.

“The crowd does seem to be picking up now. It’s getting thicker, and you can hear them singing now in the background, ‘Glory, Glory Hallelujah.’” -Radio reporter Jeff Guylick

Holmes Norton: The crowd stretched so far along the Tidal Basin that you knew you could not look at the end of it. I was sitting where the march began, at the Lincoln Memorial. I saw that crowd from Lincoln’s statue itself, and you could not see the last man or woman on the Mall. That was a sight far beyond a dream in civil rights.

“It’s a pleasure being here and nice being out of jail. And to be honest with you, the last time I’ve seen this many of us, Bull Connor was doing all the talking.” -Activist and comedian Dick Gregory

Abernathy: I don’t know where that march started out. It looked like we marched forever before we got to the Mall. You were used to marching; you wear comfortable shoes so your feet won’t hurt and you don’t get blisters. We got to the stage, and Coretta [Scott King] and I sat on the second row. Mahalia [Jackson] sat on the first row, because she was singing. We were on the left side of the stage. I wanted to scream, we were so happy, we were ecstatic. We had no idea it would be that many people—as far as you could see there were heads. What I called a sea of people; because all you could see was people, everywhere, just a sea of heads and what jubilation. Which said to us in the civil rights movement: “Your work has not been in vain. We are with you. We are part of you.”

“The entire grass area from the Lincoln Memorial of the one mile to the Washington Monument is now filled with people. Some of the marchers are now in the trees in front of the Lincoln Memorial.” -Radio reporter Al Hulsen

Lewis: It was at the back side of Mr. Lincoln that Mr. Randolph and Dr. King said to me, “John, they still have a problem with your speech. Can we change this, can we change that?” I loved Martin Luther King, I loved and admired A. Philip Randolph, and I couldn’t say no to those two men. I dropped all reference to marching through the South the way Sherman did. I said something like “If we do not see meaningful progress here today, we will march through cities, towns and hamlets and villages all across America.” I was thinking about how I was going to deliver the speech. I was 23 years old, and it was a sea of humanity out there that I had to face.

“The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, is now on top of one of the television platforms above the crowd. He’s waving. The crowd is waving back to him.” -Radio reporter Al Hulsen

Horowitz: A. Philip Randolph gave a speech that is just ignored too much. He gave the speech for jobs and economic rights, and he did it with incredible power. Then my heart was in my mouth for John Lewis, the then-23-year-old SNCC leader from Troy, Alabama. If you look at that speech today, it was still the most radical. And then of course Dr. King was the culmination. Mahalia Jackson sang, not to be believed. If you look at clips of the march, you see Bayard running around and talking, he never stopped. He’s organizing everything except when Mahalia sings.

Cox: What’s interesting was not only the crowd all the way to the Reflecting Pool, but that people were up in trees, they were everywhere. When King started speaking, and as he was speaking, Mahalia Jackson began like a chant and response. She was like his amen corner. She kept saying, “Tell ’em, Rev” the whole time he was speaking. She was just talking to him.

“So far police estimate 110,000 people, but judging by the crowd that surrounds the Reflecting Pool, now it looks like it’s well over that, and might be the largest demonstration ever held in the nation’s capital.” -Radio reporter George Geesey

Bond: When Dr. King spoke, he commanded the attention of everybody there. His speech, with his slow, slow cadence at first and then picking up speed and going faster and faster. You saw what a magnificent speechmaker he was, and you knew something important was happening.

“When Martin Luther King addressed the people here, people rose and came right over to the loudspeakers, and applauded from this end, every sentence that he said.” -Radio reporter Malcolm Davis

Rosenberg: First thing, the setting: There’s Abraham Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation, that’s the whole thing—100 years since 1863. That setting was brilliant. This was part of Martin Luther King’s redefining the word “freedom.” It made me think in terms of Stalin, the Holocaust, the Jews under pharaoh, the Egyptians: The oppressor is not free either. That, to me, was the most astounding part. It was not a speech for African Americans alone; it was a speech for America, for all of us. If you were an oppressor, you’re not free.

If you see video of the march, you’ll see people walking around during Dr. King’s speech. It was almost like a family reunion on a huge scale. People were not standing stiff, they were listening intently, but they were moving around, talking to each other.

Holmes Norton: Martin Luther King gave the triumphant speech that propelled the movement forward. It would be a mistake, though, to see the march as “one such speech,” “one such song after another” that wowed the crowd. They were there to witness the march, not just the King speech, which was the glorious crescendo, as it were, to the day.

Ladner: Medgar Evers’ death was a subtext of the march. Everyone was aware that one of the truly great heroes in the Deep South had just been murdered. And therefore, Mr. President, your request that we go slow doesn’t make sense.

“More and more people are beginning to feel the results of the heat here and of the close quarters, particularly those up front right near the Lincoln Memorial. Every few moments, it seems that someone is being lifted over the fence to the Red Cross people, put on a stretcher and taken to one of the first aid tents. Another woman has just been brought over the fence.” -Radio reporter Al Hulsen

The aftermath of the March on Washington

Lewis: After the march, President Kennedy invited us back down to the White House, he stood in the doorway of the Oval Office, and he greeted each one of us, shook each of our hands like a beaming, proud father. You could see it all over him; he was so happy and so pleased that everything had gone so well.

Horowitz: The podium sort of cleared. Those of us who had worked on the march, the staff people and the SNCC staff, stood at the bottom of the memorial. We linked arms and we sang “We Shall Overcome,” and we probably cried. There were some SNCC people who were cynical about Dr. King, and we forced them to admit it was really a great speech.

“On the podium now, directions are being given the demonstrators, as they’ve been called officially, as they return to their [shuttle] buses, and from buses to trains and to homes all over the country. A cloud has just darkened this area in front of the Lincoln Memorial, but the Reflecting Pool is in sunlight. Congress is brilliantly silhouetted against the sky, and flags are waving.” -Radio reporter Al Hulsen

Ladner: After the march, all the people had left, and a group of SNCC people were standing there with remnants of things to clean up. This small group of people had to go back south. We were dedicated to going south, to take this giant problem on, fighting the problem we had left behind.

My sister Dorie and I walked back to the hotel. In the lobby, Malcolm X was holding forth. He was talking about the “Farce on Washington.” Reporters and others were crowded around him. His ideal would have been, you take your freedom, grab it, not ask the government to free you. I do recall very clearly wondering who was right, King and us or Malcolm?

Howard: When I got home, my mother was watching parts of Martin Luther King’s speech on TV (black-and-white of course). You could feel the gravity there. It’s difficult for someone these days to understand what it was like, to suddenly have a ray of light in the dark. That’s really what it was like.

“People are streaming out very rapidly.” -Radio reporter Ken Hulsen

“Directly in front of me are some of the same people that have been here since about 11:30 this morning. They look as though they can barely move. And I’m sure that a great deal of them haven’t had sleep for one or two days and can’t expect any tonight.” -Radio reporter Malcolm Davis

The legacy of the March on Washington

Holmes Norton: Marches strive for effects, but they don’t usually, immediately, see those effects. While the march was not the cause of the legislation, it is hard to believe that the 1964 Civil Rights Act would have occurred without it. It helped move the Kennedy administration from doubt and resistance to the march. Remember President Kennedy was dependent upon not only Southern votes, but Southerners chaired virtually all the committees in the House and the Senate. One has to understand just how antediluvian the Congress was and the nation was. This was a nation where there were no federal laws that said that anybody who could do a job was entitled to do the job.

Cox: It was the moment that America got the question answered that it had been asking since 1955 or even 1954 in Brown v. Board [of Education]: What do these Negroes want? I think that King’s speech answered that question by saying, “I have a dream that is deeply rooted in the American dream.” King said what we want to do is fulfill the promise of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Howard: One thing about the march: It was a step. You have to realize the tumultuousness of the times. Just a few weeks later, four little Black girls got blown up at a church in the South. After the march, you had the feeling that things will change—and then these little girls were killed. As they said about the walk on the moon, it was a “small step,” but it was a step nonetheless that people heard. The loss of those girls was sad, but it was another step, because individuals began to see there was an injustice being done.

Only in retrospect do you see just how each little piece enabled a building to be built. Who would have thought a minister from a small Black church in Atlanta would have a monument on the Mall? You wouldn’t think a minister from a small Black church would be a “drum major” in a movement helping a people gain their rights as citizens. It’s only from the mountaintop of time that you see that it all made a difference. Each individual thing played a role.

“A lot of paper is littered on the grounds, and men with the usual sharp sticks and little bags are going around trying to get most of it up so that the site is back to normal by tomorrow morning.” -Radio reporter George Geesey

Rosenberg: I was a young man—out of the Army, married, two weeks later my son Scott was born. One thing I kept in my heart was that when this child was born, he would know about these things. When he was old enough, I would take him to demonstrations.

Young: We suddenly realized that this turned us from a Southern Black movement into a national multiracial human rights, an international multiracial human rights movement. Ironically, when we had the news reports from Birmingham, they put the dogs on us but nobody said why. They didn’t say they put the dogs on us because they were trying to register to vote. That never came through. Or they were in places trying to apply for jobs and they ran them out with dogs and fire hoses. Everybody had a 90-second view of the movement from the 6 o’clock news. And this gave them an opportunity, especially in Martin’s speech, to put it in the context. He was talking about the Declaration of Independence being a gigantic promissory note and that it promised freedom and dignity. But it was issued as a promissory note for the future. When the Negro presented his note at the bank of justice and freedom, his was the only one that came back marked “insufficient funds.” We had defined the movement as to redeem the soul of America from the triple evils of racism, war and poverty. And this was an attempt to raise the question of jobs and freedom and the ballot. It was a statement of faith not only as a movement but in the United States of America.

“We feel that the real hero of this occasion is those thousands of people who came from all over.” -Activist and actor Ossie Davis

Horowitz: After the march, Bayard told me that he had some time alone on the podium with Mr. Randolph. And he said, “Chief, this is your vision, your dream. It’s come true at last.” He said that he saw tears in Mr. Randolph’s eyes.

:focal(448x298:449x299)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/25/8d257465-39cf-4ce8-add6-23c7fa55645c/julaug13_n05_marchonwashington-963-1.jpg)