The Original Women’s March on Washington and the Suffragists Who Paved the Way

They fought for the right to vote, but also advanced the causes for birth control, civil rights and economic equality

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/79/aa795e05-84b8-4276-b156-6e5f6eb7c363/1024px-head_of_suffrage_parade_washington.jpg)

Following on the heels of President Donald Trump's inauguration this Friday, at least 3.3 million Americans gathered for marches around the country, rallying behind calls for a Women's March on Washington—though the rallies ultimately spready to many cities worldwide. In Washington, D.C., alone, crowd estimates were around 500,000, with protestors calling for gender equality, protection for immigrants, minority and LGBTQ rights and access to women's health services.

But it wasn't the first time huge crowds of women turned out to make demands of the government. On March 3, 1913, one day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, more than 5,000 women descended on Washington to fight for the vote. Some came on foot, some on horseback, some in wagons. There were costumes and placards and about half-a-million spectators lined the streets. Among the marchers were journalist Nellie Bly, activist Helen Keller and actress Margaret Vale—who was also the niece of the incoming president (who was by no means an ally of the suffrage movement; he once said women who spoke in public gave him a “chilled, scandalized feeling”). Despite being heckled and harassed by the crowd, the march was enormously memorable; six years later Congress passed the 19th Amendment, extending the franchise to women nationwide.

With the approach of another march on Washington led by women, delve into some of the forgotten members of the original Women’s March. From young “militants” who learned their tactics from British suffragists to African-American activists who fought their battle on multiple fronts, these women prove that asking for respect often isn’t enough. As Sojourner Truth said, “If women want any rights more than they’s got, why don’t they just take them, and not be talking about it?”

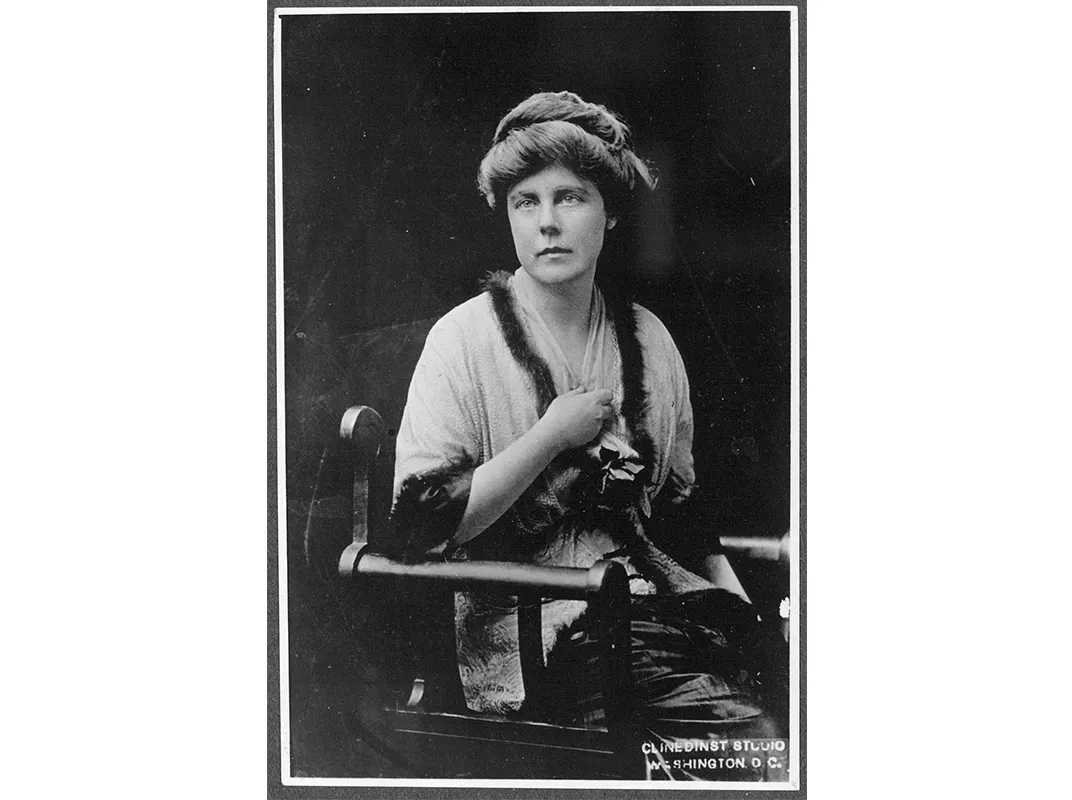

Inez Milholland

Suffragist, pacifist, war correspondent and aristocrat, Inez Milholland’s reputation as a beauty was matched by her tenacity. Raised in New York and London, Milholland made an early name for herself in suffrage circles by yelling “Votes for Women” through a megaphone out of an upper-story window during a campaign parade for President Taft in 1908. After graduating from Vassar in 1905, she applied to graduate school and was rejected by several Ivy League universities on the basis of her sex, before finally gaining admission to New York University to study law. She used the degree to push for labor reform and workers’ rights.

Milholland was at the very head of the suffrage march, dressed in a long cape and riding a white horse. She made a striking figure and proved suffragists could be young and beautiful at a time “when suffragists were derided for being unfeminine and lacking respectability.” After the march, Milholland continued to advocate for women’s rights until her untimely death in 1916 at age 30, where she collapsed onstage at a suffrage event in Los Angeles. The last words of the speech: “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?”

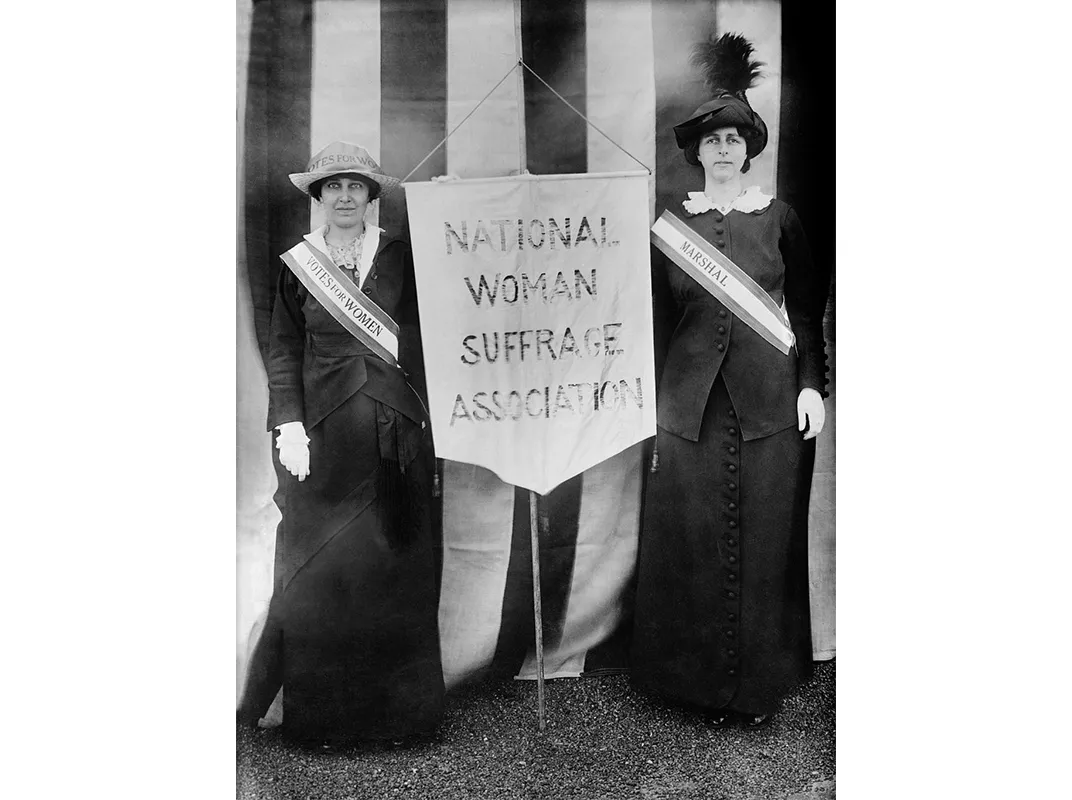

Lucy Burns

In a meeting that seemed almost pre-ordained, the Brooklyn-born Lucy Burns encountered suffragist Alice Paul at a London police station, having both been arrested for protesting. The two began talking after Paul noticed Burns was wearing an American flag pin, and they commiserated over America’s lackluster suffrage movement compared to the more aggressive British campaign for the vote. The two went on to organize the Women’s Suffrage March of 1913 together.

Burns was also the founder of the National Woman’s Party, a militant wing of the movement that borrowed techniques Burns had learned in London, including hunger strikes, violent clashes with authorities and jail sentences. She would ultimately spend more time in prison than any other suffragist. But she gave up her career in aggressive activism in 1920, after the women’s vote had been secured, and spent the rest of her life working for the Catholic Church.

Dora Lewis

Like Lucy Burns, Dora Lewis wasn’t one to shy away from confrontation or jail time. The wealthy widow from Philadelphia was one of Alice Paul’s earliest supporters, and served on multiple executive committees of the National Woman’s Party. In November 1917, while protesting the imprisonment of Alice Paul, Lewis and other suffragists were arrested and sentenced to 60 days in the notorious Occoquan Workhouse. Lewis and other inmates staged a hunger strike, demanding to be recognized as political prisoners, but their strike quickly turned horrific when the guards began beating the women. In what would later be called the “Night of Terror,” Lewis and others were handcuffed and force-fed with tubes pushed into their noses. Lewis described herself as “gasping and suffocating with the agony of it” and said “everything turned black when the fluid began pouring in.” Despite her traumatic experiences at the prison, Lewis stayed active in the movement until the right to vote was secured.

Mary Church Terrell

Born to former slaves in Memphis, Tennessee, Mary Church Terrell was a woman of many firsts. She studied at Oberlin College in Ohio, becoming one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree in 1884. She went on to earn her master’s and then became the first African-American woman appointed to a school board. Her husband, an attorney named Robert Heberton Terrell, was Washington, D.C.’s first African-American municipal judge.

But for all her accomplishments, Terrell struggled with participating in national women’s organizations, which often excluded African-American women. At a speech before the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1904, Terrell demanded, “My sisters of the dominant race, stand up not only for the oppressed sex, but also for the oppressed race!” Terrell continued her work long after the march, becoming a charter member of the NAACP and helping to end segregation in restaurants of Washington by suing a restaurant that refused to provide service to African-American customers.

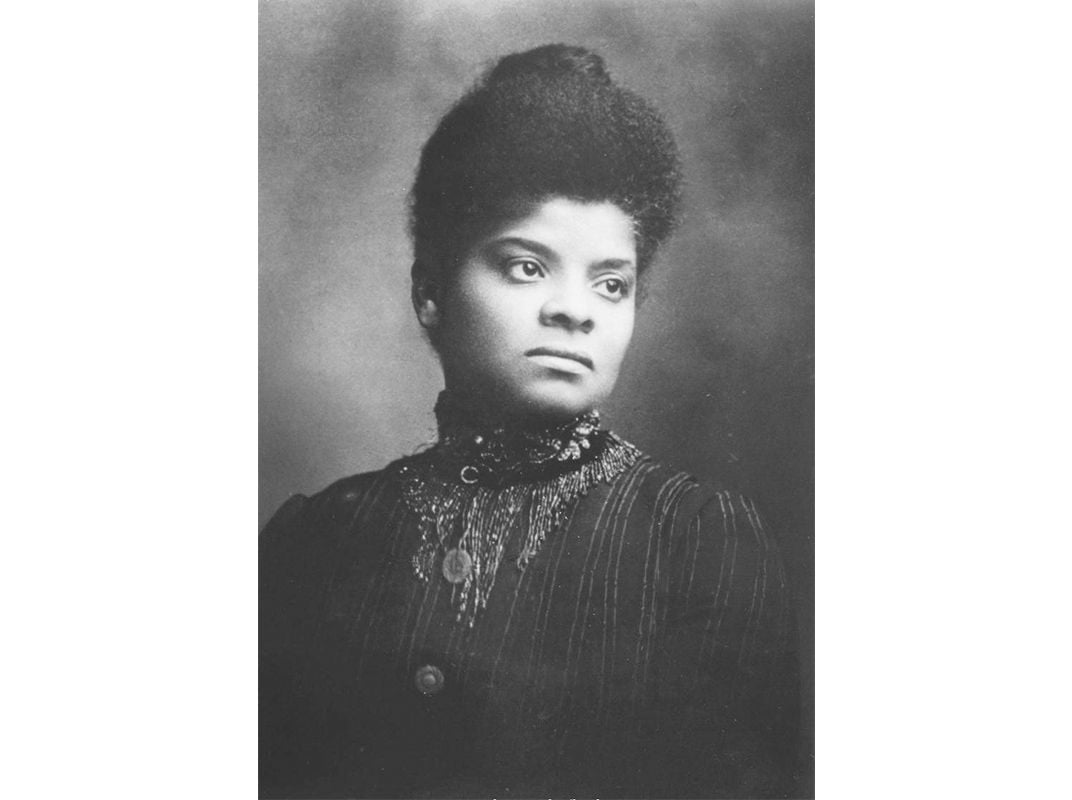

Ida B. Wells

Like Mary Church Terrell, Ida Wells combined her suffragist activities with civil rights. Early in her career as an activist she successfully sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad company for forcibly removing her from the first-class area to the colored car; the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed her victory shortly thereafter, in April 1887. She worked mainly as a journalist under the penname “Iola,” writing editorials on poverty, disenfranchisement and violence against African-Americans. In 1892, one of her friends was lynched after defending his store from attack, and in her grief and anger she turned her pen to lynchings.

At the 1913 march, Wells and other African-American women were told they would be segregated from the main group, and would march at the end. Wells refused, waiting until the procession started and then joining the block of women that represented her state.

Katherine McCormick

Though intensely active in the women’s suffrage movement (at times serving as treasurer and vice president of NAWSA), Katherine McCormick’s legacy stretches far beyond the right to vote. The Chicago native saw her father die from a fatal heart attack when she was only 14, and her brother died of spinal meningitis when she was 19, prompting her to study biology. She enrolled in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earned her B.S. in biology in 1904, after sparring with the administration over her refusal to wear a hat in the lab (hats were required for women), saying it posed a fire hazard. Many years later, McCormick donated a chunk of her inheritance to MIT so they could build female dormitories and boost women’s enrollment.

McCormick was also a key player in the creation of the birth control pill. After meeting with scientist Gregory Pincus in 1953 to discuss creating an oral contraceptive, she began making annual contributions of over $100,000 to help with the cost of research. She also smuggled illegal diaphragms in from Europe so they could be distributed at women’s health clinics. Her contributions proved invaluable, and the birth control pill came on the market in 1960. When McCormick died in 1967 she proved her dedication to women’s rights, leaving $5 million to Planned Parenthood.

Elizabeth Freeman

Like other suffragists who spent time in England, Elizabeth Freeman was galvanized by repeat encounters with law enforcement and multiple arrests. She turned the difficult experiences into fodder for speeches and pamphlets, working with suffrage organizations around the United States to help them gain more media attention. Freeman was a master of manipulating public spaces for publicity, such as speaking between rounds of prize fights or at the movies. In the summer of 1912 she campaigned through Ohio, driving a wagon and stopping in every town along her route to pass out literature and speak to curious onlookers. She employed this same technique at the march. Dressed as a gypsy, she drove her wagon past the crowds, trying, as always, to engage her audience.

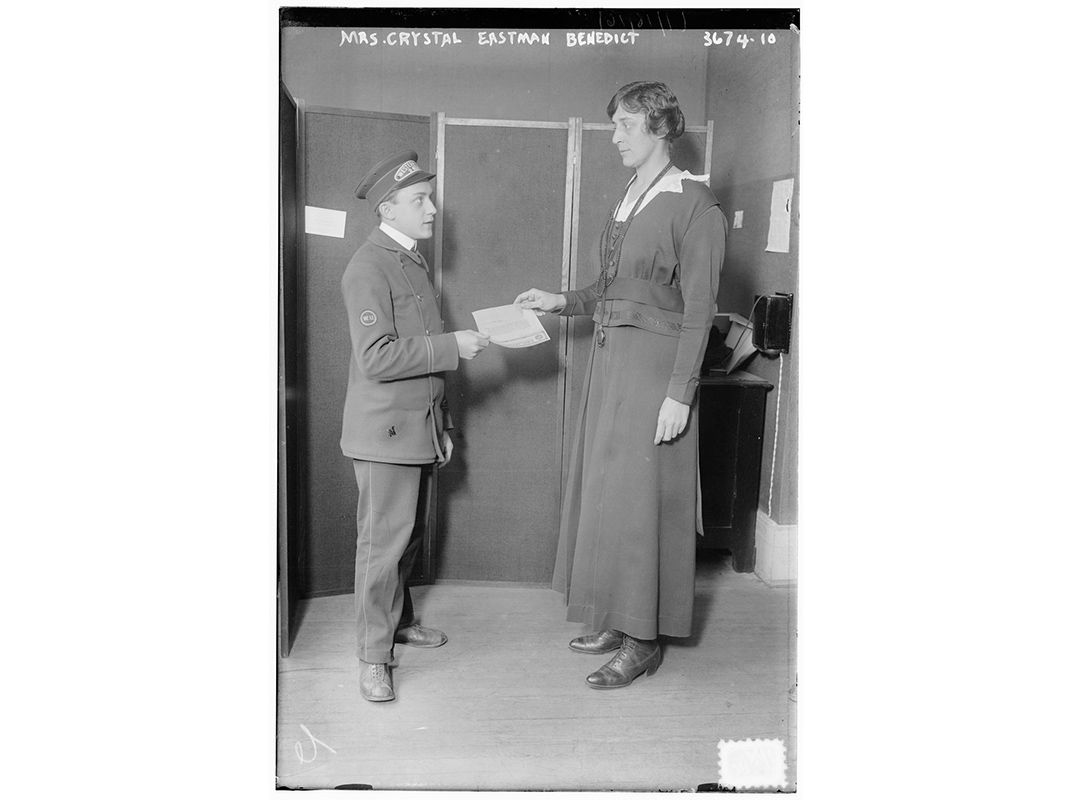

Crystal Eastman

Crystal Eastman, another Vassar graduate like Lucy Burns, spent most of her life fighting for women’s rights, long after they attained the right to vote. She also participated in labor activism (writing a study called “Work Accidents and the Law” that helped in the creation of workers’ compensation laws) and chaired the New York branch of the Woman’s Peace Party. Eastman organized a feminist Congress in 1919 to demand equal employment and birth control, and following the ratification of the 19th Amendment, Eastman wrote an essay titled “Now We Can Begin.” It outlined the need to organize the world so women would have “a chance to exercise their infinitely varied gifts in infinitely varied ways, instead of being destined by the accident of their sex.” The essay still resonates today in its call for gender equality in the home, financial support for motherhood, female economic independence and voluntary motherhood.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)