Part of Being a Domestic Goddess in 17th-Century Europe Was Making Medicines

Housewives’ essential role in health care is coming to light as more recipe books from the pre-Industrial Revolution era are digitized

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/e1/3ae1da7a-967c-42f4-adcf-a86e244fe38b/medicinal_plants.jpg)

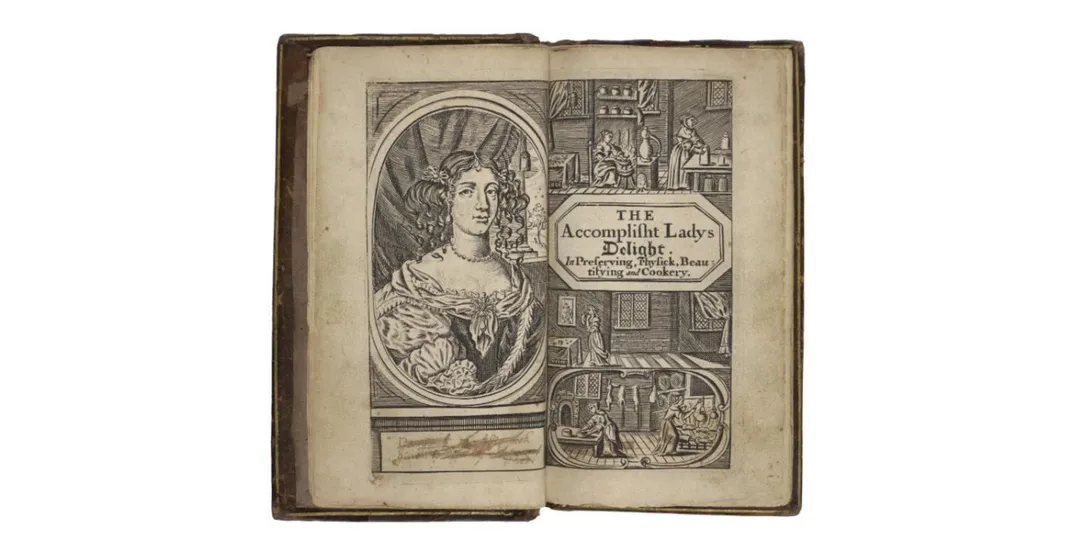

Hannah Woolley is often called the Martha Stewart of the 17th century, but a more apt comparison might be wellness guru Gwyneth Paltrow, founder of the lifestyle brand Goop. That’s because Woolley, author of the first books on household management and cookery published in English, didn’t just provide recipes for eel pie and hot chocolate wine alongside tips on seasonally decorating your mantel with mosses and mushrooms. She also offered up recipes for cosmetics, shampoos and medicines—even a guide to performing minor surgery. To treat sore throats, she recommended a syrup of violets. To reduce smallpox scarring, a lemon and sea salt wash. For breast cancer, an ointment of goose dung and juice of the celandine flower, a member of the poppy family.

For housewives in pre-Industrial Revolution Europe, it wasn't enough to know how to cook a good meal, they were also expected to know how to make medicines and treat sick members of their household. While this was likely a worldwide phenomenon (Lady Jang Gye-hyang wrote the first cookbook in Korean in 1670), Europeans left a massive trove of evidence to scrutinize. With increased efforts to digitize all of these texts, the recipes can finally be transcribed and analyzed—and sometimes even revived.

“There was a strong expectation that women from all walks of life would know how to make household remedies, treat common ailments, and care for the sick. Some women with skilled hands and inquiring minds went beyond baseline expectations to become renowned healers in their local communities or further afield,” says Sharon Strocchia, a historian at Emory College and author of Forgotten Healers: Women and the Pursuit of Health in Late Renaissance Italy.

Housewives would often meticulously compile their remedy recipes in “commonplace” household books that would be passed down to future generations. They’d ask friends, family members and medical professionals for their recipes, which they then eagerly copied into notebooks. Next, the lady and her servants would test and tweak each recipe. Only those that passed muster would be adopted in the household repertoire. Women collected recipes for balms, distillations and elixirs to treat all manner of ailments: from headache, fever, indigestion, weakness, palsy, dropsy and “trapped wind” to acne, melancholy, childbirth or menstrual pain, rickets and plague. (The Essex, England-native Woolley was an outlier for publishing her books for the general public, and she became a household name because of it.)

Curators at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. and the Wellcome Library in London have put a lot of effort into gathering together and digitizing these household recipe books. So far, hundreds have been found. University groups, scholarly websites and blogs are contributing by transcribing these valuable records. The Early Modern Recipes Online Collective instituted an annual transcribathon in 2015. This year’s event takes place on March 4. With more and more recipe books available to study, the significant contributions women made to health care during this era are coming to light.

Last fall, history professor Stephanie Koscak and her students at Wake Forest University began a public history project transcribing and analyzing early modern (16th to early 19th century) recipe books. They quickly learned that the boundaries between professionalized medicine and more vernacular forms of health care were much more porous at the time than they are today.

Women were increasingly unwelcome in medical professions. “University-trained physicians often excoriated ‘silly’ women, ‘old wyves’ and ‘toothless, wrinkled, chattery, superstitious taper-bearing old women’ who dared to meddle in medicine,” Strocchia explains. But universities didn’t teach much more than Christian theology, philosophy and humoral theory, which still dominated medical thinking even though it was first popularized in Ancient Greece.

Illness was thought to be caused either by a blockage of a flow within the body or by an imbalance of the four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, phlegm). Most medicines aimed to rebalance the humors or restart the flow. Bloodletting was used to relieve a fever, cucumbers to cure a rash, wine to aid digestion. Foods could also cause imbalance: mustard and the brightly colored edible flower nasturtium produced reddish bile, lentils and cabbage black bile, and leeks, onions, and garlic created evil humors in the blood.

Lay women practitioners might’ve had more experience tending actual patients than male physicians. The treatments women recommended were often much less intense than those prescribed by licensed doctors, who favored purgatives, laxatives, blood-letting and toxic metals. These “heroic” methods could do more harm than good.

Famous 16th-century English philosophers Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes both preferred women healers. Bacon found “old women more happy many times in their cures than learned physicians.” Hobbes would “rather have the advice or take physic from an experienced old woman that had been at many sick people’s bedsides, than from the learnedst but unexperienced physician.”

It’s important to remember, Strocchia says, that back then, university-trained physicians only represented a small fraction of the health care profession. “Other practitioners, ranging from midwives and apothecaries to bone setters and barber-surgeons, played a prominent role in healing,” she says. Women were essentially acting as pharmacist, family physician and EMT all rolled up in one.

“Even when women are not necessarily working in what we would think of now as a professionalized medical role, they're still employing the kinds of terminology, epistemological systems, and empiricism that are being employed within those professional communities,” Koscak says.

To test the efficacy, safety and reliability of the recipes they’d collected, women used the same standards of empirical observation as their professional counterparts. They’d recreate the medicine, conduct trials on household members, observe the effects, then decide if any adjustments were needed. Hiding beneath the denigrated labels “domesticity” and “housewifery” was keen scientific aptitude and daily involvement in knowledge-building endeavors.

Home health care was an essential survival skill for families. Modern hospitals, staffed with trained physicians and surgeons, didn’t appear until well into the 1700s. Before that, such care was often delivered in connection with religious organizations in temples, convents or monasteries, which offered a mishmash of medical care and charity for the poor.

“The social expectation that most women would be proficient in pharmacy helped foster a broader culture of experimentation that presaged the development of modern medicine,” Strocchia notes.

In addition to medicines for specific ailments, housewives had general preparations to treat or prevent a wide variety of illnesses or perk you up when you’re feeling run down. Aqua mirabilis, or “miracle water,” was one of the most popular cure-alls of the 17th century. It was typically made by infusing a mix of brandy, wine and celandine juice with cloves, mace, cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, ginger, sweet clover, spearmint, rosemary and cowslip for 12 hours, then distilling it into a cordial.

Elaine Leong, a history professor at University College London and author of Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science and the Household in Early Modern England, has found 259 collections of early modern household recipe books at 12 research libraries in the U.K. and U.S. In her analysis of 9,000 medicine recipes, she found 3,000 different ingredients. The most common were herbs, spices and animal products. Among the favorites were rosemary, nutmeg, saffron, cinnamon, elderberry, turnip, angelica, poppy, lemon, thistle, sage, lavender, clary, aniseed, coriander, fennel and caraway. Salves and plasters typically used animal fat as a base; the alcohol base of distilled waters and cordials helped lengthen their shelf life. Herbs would have been grown in the garden, sugar and spices purchased at the grocer’s. Medicines could be made by the gallon, with dosages by the pint.

For prominent, wealthy women, making and administering medicines to their entire community was seen as a requisite charity activity. When Lady Grace Mildmay of Northamptonshire died in 1620, she left behind 250 folios of medical writings describing how to prepare and dispense herbal and chemical medicines. Her recipe for one particularly complicated balm involves mixing 13 pounds of sugar and nuts and 159 different seeds, spices, and roots into eight gallons of oil, wine, and vinegar. Her memoir is considered one of the earliest autobiographies authored by a woman in English; excerpts from it were first published in 1911.

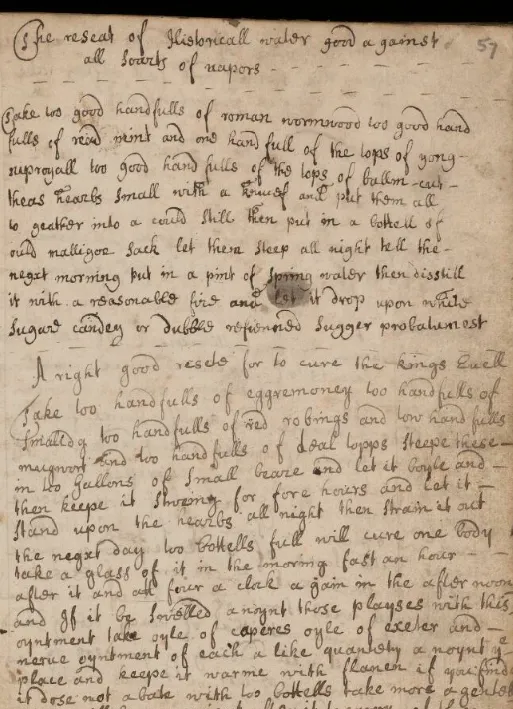

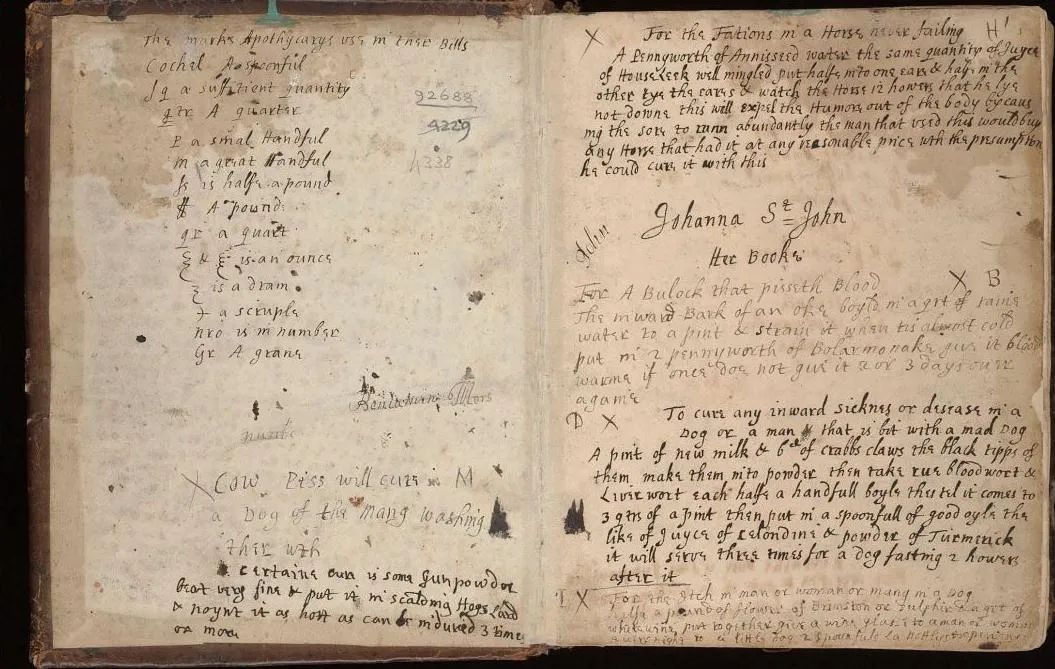

Over the course of her life, Lady Johanna St. John compiled an alphabetical list of medical remedies in a small leather-bound notebook; she believed this treasured collection important enough to include in her will. Johanna and her husband lived in Battersea, but summered at their country estate near Swindon. She had 13 children, yet still found time to micromanage her household staff on exactly how to brew beer and distill medicines.

“Johanna’s detailed instructions, including specific directions to contact local experts for particular ingredients, give a clear picture of how one gentlewoman can ‘make’ medicines via ‘remote control’,” Leong notes.

Memoirist Elizabeth Freke, born Norfolk, England, in 1641, created an inventory of over 400 home remedies and kept her 200 bottles of medicine under lock and key. Most of the medicines she kept ready-made were cure-alls. One of her notebooks contains 300 medical recipes and 200 culinary ones. Some recipes were copied from published medical texts and pharmacopeia, or pharmaceutical recipe books published by professional medical associations. Her texts now live in the British Library.

Household recipe collections were precious, multi-generational heirlooms, considered to be very valuable for “helping the family anticipate possible illnesses and for guaranteeing the social reproduction of the family itself,” Koscak says. Sometimes the books were published, but their main value rested in recipe exchange, “that sharing of knowledge that can consolidate networks of women's friendship.”

The working class, often being illiterate, may not have had their own family recipe book, but that doesn’t mean these women weren’t involved in the practice of home health care. Important recipes could be passed down orally. And servants in upper and middle class households would be doing most of the grunt work involved in mixing up these recipes. The books had diagrams the servants could follow. Woolley herself was once a servant, who began writing books out of financial necessity after being widowed—twice.

Koscak says that many of her students tried recreating recipes since they were stuck at home in the pandemic. This quickly became a crash course in household labor dynamics. “They got to the part of the recipe that said ‘beat the eggs for 45 minutes’ and went ‘Oh my God!’ That would’ve been a servant’s job.”

The wide range of recipe types found in these household collections, often in no particular order—meals, medicines, cosmetics, cleaning products—might seem like “a hodgepodge,” as Koscak puts it, but there’s a good reason for this lack of differentiation.

“In this period, many ingredients used in foods were thought to have important medicinal properties. So there's not necessarily a distinction between cookery and medical preparations,” Koscak says. “Even in terms of the creation process, they're using the same knowledge and instruments as food preparation.”

What can’t be overstated is that these housewives normalized a spirit of scientific inquiry and encouraged scientific experimentation as an everyday activity.

“The growing split between ‘professional’ medicine and home-based health care has led to a devaluation of experimental practices that took place in the home,” says Strocchia. “Scholars are just now beginning to recognize that women played an enormously important role as household healers for many centuries, both as makers of medical remedies and as everyday caregivers.”

Many of the remedies found in these centuries-old books contain ingredients with medicinal or immune-boosting properties. In the case of Woolley’s ointment, goose dung won’t fight cancer, but celandine extract might.