A Pearl Harbor Disappearance May Finally Have Been Solved

Flight instructor Cornelia Fort faced a close call on that infamous day, but her plane was thought to have been lost to history

:focal(490x199:491x200)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/ed/3aed0db8-8623-44a0-af55-a901477d452c/nov2016_h03_phenom-wr-v2.jpg)

Early in the morning on December 7, 1941, a 22-year-old civilian flight instructor named Cornelia Fort happened to be airborne over Honolulu, giving a lesson to a student who was at the controls of an Interstate Cadet, a tiny single-engine trainer. As they turned and headed back toward the city airfield, the glint of a plane in the distance caught her eye. It seemed to be heading right at them, and fast. She grabbed the stick and climbed furiously, passing so close to the plane that the little Cadet’s windows shook.

Looking down, she saw a Japanese fighter. Off to the west, she “saw something detach itself from a plane and come glistening down,” she later recalled. “My heart turned over convulsively when the bomb exploded in the middle of the Harbor.” Fort and her student landed at the airport and ran to the terminal as a warplane strafed the runway. “Flight interrupted by Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor,” she later noted in her logbook.

Her close encounter, widely celebrated in the wake of Pearl Harbor, is re-enacted in the opening scenes of the movie Tora! Tora! Tora! and at air shows even today. Her plane, though, appeared lost to history.

Now, as the 75th anniversary of the attack approaches, a former fighter pilot thinks he’s found it. Retired Air Force Lt. Col. Greg Anders, executive director of the Heritage Flight Museum in Burlington, Washington, knows that the Interstate Cadet he bought from a collector in 2013 was in Honolulu at the time of the attack; FAA records prove it.

But showing that it’s the one that Fort flew has taken some detective work. That’s because the registration number on his aircraft, NC37266, isn’t the same as the number penned in her logbook, NC37345. Why the difference? He argues that her logbook, which is archived in the Texas Woman’s University Libraries, is not the original document but a copy she made after a December 1942 fire at her family’s Nashville home destroyed many of her belongings. Anders discovered that the registration number in her logbook belonged to an aircraft that hadn’t even been built by the time of her first notation. Of the 11 other Cadets that have a paper trail to Pearl Harbor, Anders says he’s got the one that best fits the timing and description of Fort’s. The full story of Fort and her legendary plane appears in an Air & Space/Smithsonian collector’s edition out this month, “Pearl Harbor 75: Honor, Remembrance, and the War in the Pacific.”

It makes sense that a young pilot looking forward to a flying career would take pains to reconstruct her logbook, Anders says: “You don’t show up at an airline interview as a female in 1945 and say, ‘I have this many flying hours, but I can’t prove that because my logbooks burned up in a fire.’ You’ve got enough trouble because you showed up as a female.”

Fort developed a reputation as a home-front hero after Pearl Harbor. She soon returned to the mainland and joined the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), a civilian group created by the Army Air Forces to fly military aircraft from factories to bases. In March 1943, she was flying formation in a Vultee BT-13 trainer over Texas when another plane clipped hers. She crashed before she could bail out—the first woman pilot to die in active service.

Related Reads

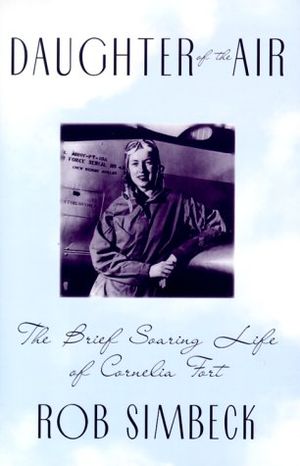

Daughter of the Air: The Brief Soaring Life of Cornelia Fort