Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu

The city sought to sell bonds to pay for the war effort, while bringing its citizens together during the infamous pandemic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/4b/3a4b6864-b224-4c72-a0d9-749664c7a403/liberty-bond-parade-cropped-web.jpg)

It was a parade like none Philadelphia had ever seen.

In the summer of 1918, as the Great War raged and American doughboys fell on Europe’s killing fields, the City of Brotherly Love organized a grand spectacle. To bolster morale and support the war effort, a procession for the ages brought together marching bands, Boy Scouts, women’s auxiliaries, and uniformed troops to promote Liberty Loans –government bonds issued to pay for the war. The day would be capped off with a concert led by the “March King” himself –John Philip Sousa.

When the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive parade stepped off on September 28, some 200,000 people jammed Broad Street, cheering wildly as the line of marchers stretched for two miles. Floats showcased the latest addition to America’s arsenal – floating biplanes built in Philadelphia’s Navy Yard. Brassy tunes filled the air along a route where spectators were crushed together like sardines in a can. Each time the music stopped, bond salesmen singled out war widows in the crowd, a move designed to evoke sympathy and ensure that Philadelphia met its Liberty Loan quota.

But aggressive Liberty Loan hawkers were far from the greatest threat that day. Lurking among the multitudes was an invisible peril known as influenza—and it loves crowds. Philadelphians were exposed en masse to a lethal contagion widely called “Spanish Flu,” a misnomer created earlier in 1918 when the first published reports of a mysterious epidemic emerged from a wire service in Madrid.

For Philadelphia, the fallout was swift and deadly. Two days after the parade, the city’s public health director Wilmer Krusen, issued a grim pronouncement: “The epidemic is now present in the civilian population and is assuming the type found in naval stations and cantonments [army camps].”

Within 72 hours of the parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was filled. In the week ending October 5, some 2,600 people in Philadelphia had died from the flu or its complications. A week later, that number rose to more than 4,500. With many of the city’s health professionals pressed into military service, Philadelphia was unprepared for this deluge of death.

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War

This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I―and how it could happen again.

Attempting to slow the carnage, city leaders essentially closed down Philadelphia. On October 3, officials shuttered most public spaces – including schools, churches, theaters and pool halls. But the calamity was relentless. Understaffed hospitals were crippled. Morgues and undertakers could not keep pace with demand. Grieving families had to bury their own dead. Casket prices skyrocketed. The phrase “bodies stacked like cordwood” became a common refrain. And news reports and rumors soon spread that the Germans –the “Huns” – had unleashed the epidemic.

The earliest recorded outbreak of this highly virulent flu came in March 1918, as millions of men volunteered or were conscripted into service. Some of the first accounts of an unusual deadly illness came from rural Kansas, where recruits were crowded into Camp Funston, one of dozens of bases hastily built to train Americans for combat. A large number of Funston’s trainees were checking into the infirmary with a nasty bout of “grippe,” as it was often called. Doctors were baffled as these young men –many healthy farmboys when they reported – were flattened with high fevers, wracked by violent coughing and excruciating pain. Some soon died, turning blue before choking on their own mucus and blood.

When packed boatloads of American soldiers shipped out, the virus went with them. By May 1918, a million doughboys had landed in France. And influenza soon blazed across Europe, moving like wildfire through dry brush. It directly impacted the war, as more than 200,000 French and British soldiers were too sick to fight and the British Grand fleet was unable to weigh anchor in May. American soldiers were battling German gas attacks and the flu, and on the other side of the barbed wire, a major German offensive came to a halt in June when the Kaiser’s ranks were too ill for duty.

With summer, the Spanish flu seemed to subside. But the killer was merely laying in wait, set to return in the fall and winter—typical peak flu season—more lethal than before. As Philadelphia planned its parade, bound to be a large gathering, director of public health Krusen had ignored the growing concerns of other medical experts and allowed the parade to proceed, even as a deadly outbreak raged on nearby military bases.

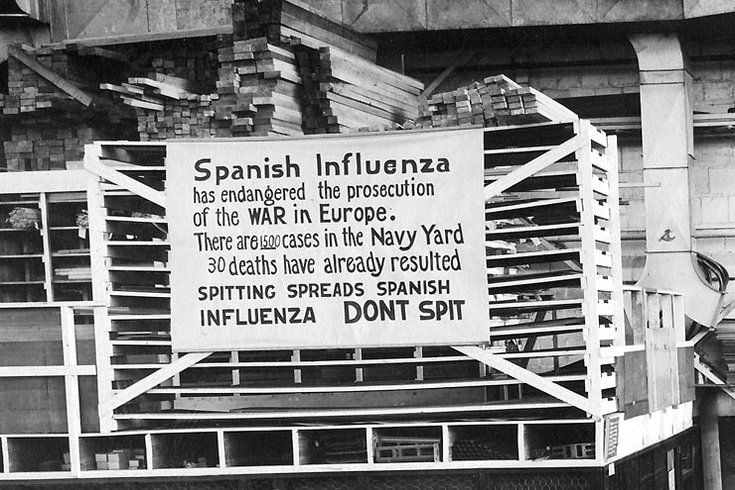

A political appointee, Krusen publicly denied that influenza was a threat, saying with assurance that the few military deaths were “old-fashioned influenza or grip.” He promised a campaign against coughing, spitting and sneezing, well aware that two days before the scheduled parade, the nation’s monthly draft call-up had been cancelled because army camps, including nearby Camp Dix in New Jersey and Camp Meade in Maryland, were overwhelmed by a conflagration of virulent influenza. Philadelphia’s parade poured gasoline on the flames.

Krusen’s decision to let the parade go on was based on two fears. He believed that a quarantine might cause a general panic. In fact, when city officials did close down public gatherings, the skeptical Philadelphia Inquirer chided the decision. “Talk of cheerful things instead of disease,” urged the Inquirer on October 5. “The authorities seem to be going daft. What are they trying to do, scare everybody to death?”

And, like many local officials, Krusen was under extreme pressure to meet bond quotas, which were considered a gauge of patriotism. Caught between the demands of federal officials and the public welfare, he picked wrong.

A few weeks prior, a parade in Boston had already played a deadly part in the pandemic’s spread. In late August, some sailors had reported to sickbay at Boston’s Commonwealth Pier with high fevers, severe joint pain, sharp headaches and debilitating weakness. With stunning speed, illness ricocheted through Boston’s large military population.

Then, on September 3, sailors and civilian navy yard workers marched through the city in Boston’s “Win-the-War-for-Freedom” rally. The next day, the flu had crossed into Cambridge, surfacing at the newly opened Harvard Navy Radio School where 5,000 students were in training. Soon all Boston, surrounding Massachusetts, and eventually most of New England faced an unprecedented medical disaster.

But there was a war to fight. Some of those Boston sailors shipped out to the Philadelphia Naval Yard. Within days of their arrival, 600 men were hospitalized there and two of them died a week before the Philadelphia parade. The next day, it was 14 and then 20 more on the next.

Sailors also carried the virus to New Orleans, Puget Sound Naval Yard in Washington State, the Great Lakes Training Station near Chicago, and to Quebec. The flu followed the fleets and then boarded troop trains. Ports and cities with nearby military installations took some of the hardest hits –underscoring the lethal link between the war and the Spanish flu.

Back in Massachusetts, the flu devastated Camp Devens outside Boston, where 50,000 men were drilling for war. By mid-September, a camp hospital designed for 2,000 patients had 8,000 men in need of treatment. Then the nurses and doctors began to drop. Confounded by this specter, one army doctor observed ominously, “This must be some new kind of infection or plague.”

Few effective treatments for the flu existed. Vaccines and antibiotics would not be developed for decades. The icon of the Spanish flu, the “flu mask” –a gauze facemask required by law in many cities – did almost no good.

Even once the war ended, famously on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the flu’s devastation did not let up. In spontaneous celebrations marking the armistice, ecstatic Americans jammed city streets to celebrate the end of the “Great War,” Philadelphians again flocked to Broad Street, even though health officials knew that close contact in crowds might set off a new round of influenza cases. And it did.

In April 1919, President Woodrow Wilson fell deathly ill in Paris—he had the flu. “At the moment of physical and nervous exhaustion, Woodrow Wilson was struck by a viral infection that had neurological ramifications,” biographer A. Scott Berg wrote in Wilson. “Generally predictable in his actions, Wilson began blurting unexpected orders.” Never the same after this illness, Wilson would make unexpected concessions during the talks that produced the Versailles Treaty.

The pandemic touched every inhabited continent and remote island on the globe, ultimately killing an estimated 100 million people worldwide and 675,000 Americans –far exceeding the war’s ghastly losses. Few American cities or towns were untouched. But Philadelphia had been one of the hottest of the hot zones.

After his initial failure to prevent the epidemic from exploding, Wilmer Krusen had attempted to address the crisis, largely in vain. He asked the U.S. army to stop drafting local doctors, appropriated funds to hire more medical workers, mobilized the sanitation department to clean the city, and perhaps most important, clear bodies from the street. It was too little too late. On a single October day, 759 people died in the city and more than 12,000 Philadelphians would die in a matter of weeks.

After the epidemic, Philadelphia officially reorganized its public health department, which Krusen continued to lead until he joined the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science, the nation’s oldest pharmacy school. He served as president of the school from 1927 to 1941, before his death in 1943.

As the nation and the world prepare to mark the centennial of the end of “The War to End All Wars” on November 11, there will be parades and public ceremonies highlighting the enormous losses and long-lasting impact of that global conflict. But it will also be a good moment to remember the damaging costs of shortsighted medical decisions shaped by politics during a pandemic that was more deadly than war.

Kenneth C. Davis is the author of More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War (Holt), from which this article was adapted, and Don’t Know Much About® History. His website is www.dontknowmuch.com

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.