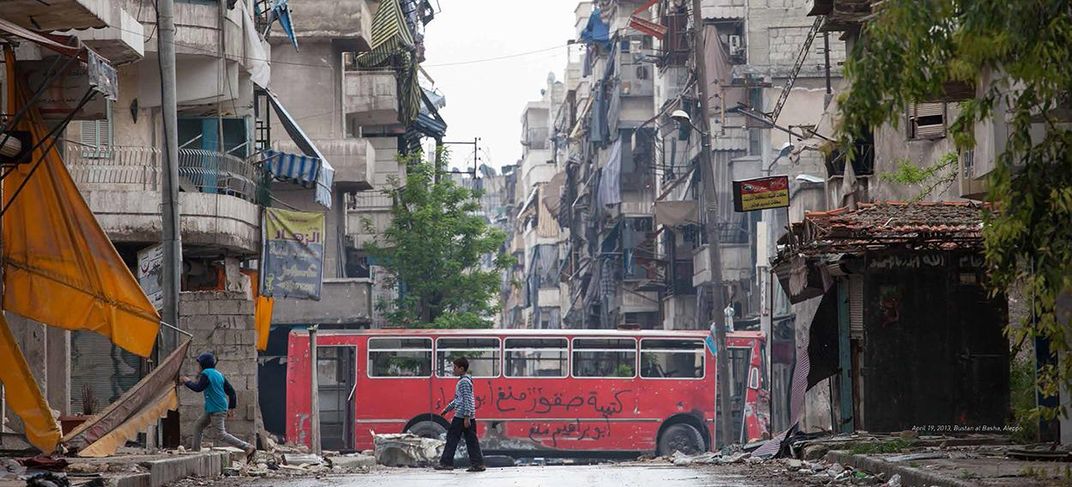

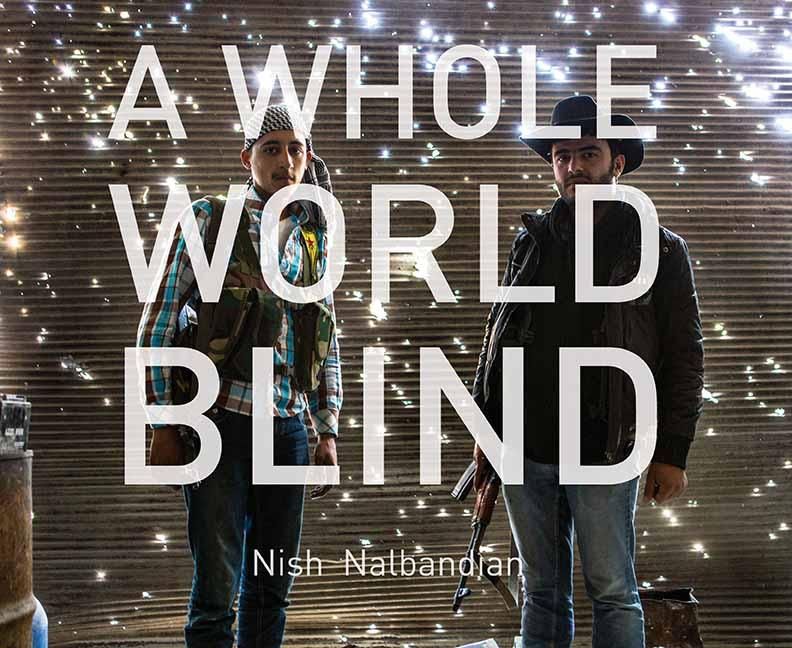

Photographer Nish Nalbandian on Bearing Witness to the Violence in the Syrian Civil War

In a new book, “A Whole World Blind,” the American photographer documents the tragedy in the Middle East

An American photographer now based in Istanbul, Nish Nalbandian has seen his photographs of the war in Syria and of Syria refugees in Turkey published by The New Yorker, The Los Angeles Times, and The Human Rights Watch World Report, among other places. He was drawn to document the violence in Syria and the refugee crisis because of his grandfather’s history as a refugee of the Armenian genocide.

In his debut monograph, Nalbandian weaves together harrowing images and powerful quotations. “I think it’s important, as Elie Weisel said, to bear witness to what you’ve seen,” he says. “I named the book A Whole World Blind because I feel like the world is not seeing what’s happening here, not really looking. It’s hard to look at things like this. And it should be.”

In a conversation with Smithsonian.com, Nalbandian discusses his book, his impulse to become a conflict photographer, and what it’s like working in such harrowing conditions.

How and when did you get into photography?

I bought my first DSLR in 2007. I only had point-and-shoots before that. I was working in another field and photography was a just a hobby for me until 2011 or 2012, when people started getting interested in some work I’d done while traveling.

How did you begin photographing the Syrian Civil War and Syrian refugees?

I went to Syria in 2009 and met people in Daraa who I remained friends with. When the war started in 2011, I was following it closely and lost touch with my friends there. I still don’t know what happened to them. When I chose to leave my previous career and become a photographer, I wanted to do something of substance, so I went back to stay with some friends in Beirut, [Lebanon], and started talking to Syrians. This led me to southern Turkey, and with the guidance of far more experienced colleagues, into Syria.

The long story, though, is that I have a photograph of my grandfather from 1916 from Syria. He was Armenian, from a village in Central Anatolia, and survived the Armenian Genocide, ending up in Syria. He joined the French Armenian Legion and fought in Syrian during the French push against the Ottomans. With my portraits I was hoping to get some of the feeling of that portrait of my grandfather.

What was shooting this conflict like?

Shooting conflict is both very difficult and very easy. It’s difficult in terms of setting it up: having insurance, doing risk assessments, setting up security plans, and working with the right people. It’s difficult in that you see things you never wanted to see, and can’t un-see. It’s difficult to see people suffer and not be able to do anything about it. But it’s easy in the sense that there is always something happening around you. The content, the subject is endless.

In a place like Syria in 2013 and 2014, you were always in danger. There was always the threat of airstrikes or artillery. There was some danger from snipers in some areas. And there is definitely unpredictability inherent in being in an environment like this. There was also a threat that many of us didn’t realize or underestimated: kidnapping. When the fullness of this risk became known, I stopped going in. Somehow the danger of working on the frontlines or in a conflict zone generally seems more manageable or understandable. You can mitigate the risks to some extent by planning and by being cautious; at least you think you can. But with kidnapping, we all pretty much stopped going into Syria because there wasn’t a way to mitigate the risk and the outcome was so damn horrifying.

Your book has portraits of young men with their weapons. Was there one young man you met fighting in the conflict whose story stayed with you?

The image of the man with his hood up, holding a rifle. I went the scene of an airstrike, and this guy had just seen the people pulled from the rubble, he’d seen that type of thing a lot. He didn’t want to give his name, but he let me take his picture and he had this haunted look that has stuck with me. I feel like you can really see the humanity in his eyes.

In the introduction, you describe injured people in the hospital and dead bodies. A few pages later, there are shots of inanimate objects that look like human body parts – an orange glove in the rubble, pieces of mannequins. Later in the book, though, you do include images of people hurt and bleeding. How did you choose to show the violence you were capturing?

I chose to start with images that were a bit more abstract or metaphorical. The images of the rubble with the glove and of the mannequins show not just destruction, but also introduce an foreboding of what the human toll might look like. It’s allegorical. But I didn’t want to leave it that way.

Regardless of what anyone says, none of us HAVE to do this work, we all have some drive or desire to do it. Something pushes us to go to places like this, and I think it’s pretty different for all of us. But at least part of this for me comes from a place of trying to show the world what is happening in the hopes that some measure of suffering can be alleviated. [Photographer] John Rowe alludes to this in his essay, which is in the text. I decided to include some of the more graphic images as well because I want the world to see them, to bear witness to what I’ve seen, to see the suffering of these people.

There’s an image of a rocket firing at night that looks like a shooting star, that’s actually seemingly beautiful at first. Can you talk about that photograph?

That image is a hard one to process. When you see something that is out of the ordinary like that, that when it first catches your eye is interesting or beautiful, but then you realize what it really is, there’s a pang of guilt. I had one when I first caught myself looking at the missiles flying out that night. You realize you’re looking at it with a photographer’s eye, but that those objects are destined to cause misery and death.

Your book includes an essay from documentarian Greg Campbell on the importance of the profession. What motivates you to go out there and do this incredibly dangerous work? Are there certain lines in Campbell’s essay you connect with?

I asked Greg to write a piece because he knows conflict, he’s a great writer, and I knew he understood where I was coming from. The part that rings most true to me is when he writes about how armed groups now have their own media in-house, and often don’t see the need to allow outside, impartial observers to see what they are doing. They want to craft their own messages and have gotten very good at it. But, as he observes, this means that the work of photojournalists is more necessary than ever. I don’t feel that comfortable saying this in my own words because I still feel relatively inexperienced compared to many of my colleagues. But reading his take on it helps to reinforce my own feelings.