How the Pledge of Allegiance Went From PR Gimmick to Patriotic Vow

Francis Bellamy had no idea how famous, and controversial, his quick ditty would become

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/26/8126efe6-d52c-4c7c-80e3-be32a92d1a10/sep2015_m04_phenom.jpg)

On the morning of October 21, 1892, children at schools across the country rose to their feet, faced a newly installed American flag and, for the first time, recited 23 words written by a man that few people today can name. “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and to the Republic for which it stands—one nation indivisible—with liberty and justice for all.”

Francis Bellamy reportedly wrote the Pledge of Allegiance in two hours, but it was the culmination of nearly two years of work at the Youth’s Companion, the country’s largest circulation magazine. In a marketing gimmick, the Companion offered U.S. flags to readers who sold subscriptions, and now, with the looming 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World, the magazine planned to raise the Stars and Stripes “over every Public School from the Atlantic to the Pacific” and salute it with an oath.

Bellamy, a former Baptist preacher, had irritated his Boston Brahmin flock with his socialist ideas. But as a writer and publicist at the Companion, he let ’em rip. In a series of speeches and editorials that were equal parts marketing, political theory and racism, he argued that Gilded Age capitalism, along with “every alien immigrant of inferior race,” eroded traditional values, and that pledging allegiance would ensure “that the distinctive principles of true Americanism will not perish as long as free, public education endures.”

The pledge itself would prove malleable, and by World War II many public schools required a morning recitation. In 1954, as the cold war intensified, Congress added the words “under God” to distinguish the United States from “godless Communism.” One atheist, believing his kindergarten-aged daughter was coerced into proclaiming an expression of faith, protested all the way to the Supreme Court, which in 2004 determined that the plaintiff, who was not married to the child’s mother, didn’t have standing to bring the suit, leaving the phrase open to review. Still, three of the justices argued that “under God” did not violate the constitutional separation of church and state; Sandra Day O’Connor said it was merely “ceremonial deism.”

Today, 46 states require public schools to make time for the pledge—just Vermont, Iowa, Wyoming and Hawaii do not. It’s a daily order of business for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. And hundreds of thousands of newly minted citizens pledge allegiance each year during the U.S. naturalization ceremony. The snappy oath first printed in a 5-cent children’s magazine is better known than any venerable text committed to parchment in Philadelphia.

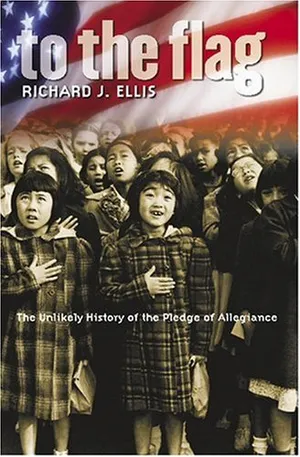

Yet the pledge continues to have its critics, with some pointing out the irony of requiring citizens to swear fealty to a nation that prizes freedom of thought and speech. The historian Richard J. Ellis, author of the 2005 book To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance, acknowledges that the oath is “paradoxical and puzzling,” but he also admires the aspirational quality of its spare poetry. “The appeal of Bellamy’s pledge is the statement of universal principles,” he says, “which transcends the particular biases or agendas of the people who created it.”

Bellamy did some transcending of his own. The onetime committed socialist went on to enjoy a lucrative career as a New York City advertising man, penning odes to Westinghouse and Allied Chemical and a book called Effective Magazine Advertising. But his favorite bit of copy remained the pledge—“this little formula,” he wrote in 1923, with an ad man’s faith in sloganeering, which “has been pounding away on the impressionable minds of children for a generation."

To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)