The Polynesian ‘Prince’ Who Took 18th-Century England by Storm

A new nonfiction release revisits the life of Mai, the first Pacific Islander to visit Britain

:focal(815x419:816x420)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/97/63978158-823c-4b70-b36e-603015348095/omai.jpg)

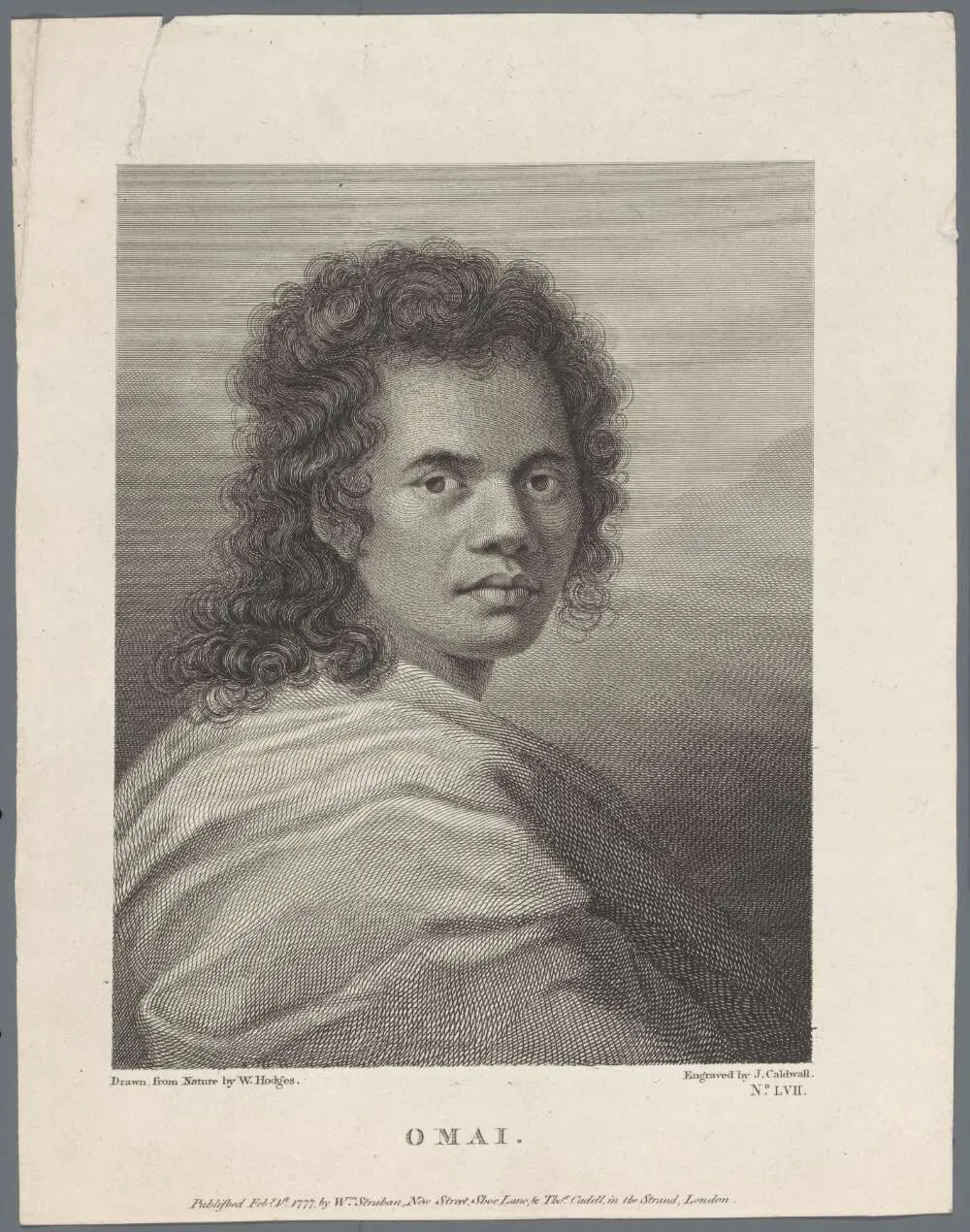

In the painting, we see a handsome, barefoot young man from the South Pacific, garbed in a flowing robe and standing before a tropical arcadian landscape. Seemingly in his early 20s, he is strapping but fine-boned, his copper skin seemingly illuminated from within. His head is wrapped in a white turban. His hands are ornately tattooed, and he has a confident, regal bearing. He appears to be a member of the South Seas aristocracy, a man of distinction, affluence, and taste, gesturing grandly as he addresses a crowd of his island subjects.

The portrait’s subject—Mai, or Ma‘i—was the first South Seas Islander ever to visit England. He arrived from Tahiti in 1774, as part of the second voyage of the celebrated navigator James Cook, and stayed in Great Britain for two years. It was a cross-hemispheric anthropological experiment that in many ways succeeded, but one that was also tinged with tragedy. In London, Mai became a sensation, a star of the press, the darling of the intelligentsia, the subject of poems, books, musical plays—and a curiosity that some of the country’s finest artists sought to paint. It’s doubtful whether any other non-European figure had inspired English portraitists to put so much oil on canvas. Indeed, few Indigenous persons had ever been so widely or vividly described, analyzed and documented by European society.

But the man immortalized on canvas was not quite the man who posed for Joshua Reynolds’ 1775 or 1776 portrait. Back in Tahiti, a society with a highly stratified system of social classes, Mai was a manahune, a commoner, powerless and impoverished. There was nothing regal or patrician about Mai; he was a nobody who happened to hitch an epic ride to England, a regular guy who went on a most excellent adventure—all of which makes his story even more spectacular.

The Exotic: Intrigue and Cultural Ruin in the Age of Imperialism by Hampton Sides

From the New York Times bestselling author of Ghost Soldiers and On Desperate Ground, the story of the Polynesian man who became the toast of 18th-century English society and whose complicated fate foreshadowed the cultural and racial reckoning of today. Available from Scribd Originals on September 15.

Part of England’s misinterpretation of Mai was his own doing. He could tell that Britain was itself a place with a rigid social hierarchy, so he did nothing to dispel the notion that he was a person of wealth and consequence back home. Mai had “allowed himself to be drawn into a new world to which he neither belonged nor comprehended,” wrote Richard Connaughton in a biography of the Polynesian. Though a willing participant, Mai would also become a victim—or, as Connaughton put it, “the foremost casualty of a social experiment that paid scant regard to its consequences.”

Mai was a native of Raiatea, a ragged volcanic island about 130 miles northwest of Tahiti. Raiatea is considered the cradle of Polynesia’s extraordinary seafaring culture. It is believed to be one of the first places where ancient navigators, coming from the west, landed several millennia ago and developed their rich civilization, which reached its apogee at Taputapuatea, a complex of marae temples that served more or less as the Vatican City of the South Seas.

Today, Raiatea, which means “faraway heaven” in the Tahitian language, still feels like a deeply spiritual place. I visited the island in early 2020, hoping to get some sense of Mai’s upbringing. It’s famous for its vanilla plantations and pearl farming and is the largest in the Society Islands’ leeward chain. In the distance to the northwest, the great slab of Bora Bora’s Mount Otemanu hangs above the glossy blue sea. On Raiatea, a certain rare flower, the tiare apetahi, grows only in one specific place, high along the volcanic slopes of Mount Temehani. Mysteriously, all attempts to transplant the flower to other islands, or even to other spots on Raiatea, have failed. The plant observes a definitive and delicate sense of place; it won’t take root anywhere else.

The same could be said for Mai. Raiatea was his home, and though he spent much of his life moving around the islands, and then traveling the world, he was never entirely at peace anywhere else.

Mai’s family owned land and enjoyed some measure of status on the island, and his early boyhood seems to have been happy. But one day in about 1763, when Mai would have been 10 or so, invaders from Bora Bora, under the command of the great chief Puni, came in their long canoes. After a three-year campaign, Puni succeeded in conquering Raiatea. His warriors killed Mai’s father and seized his family’s land. The Bora Borans ransacked much of the island and demolished the god houses at Taputapuatea, dismantling the platforms and other sacred structures. The impressionable Mai likely witnessed many traumatizing horrors.

The Bora Borans enslaved much of the Raiatean population, including Mai. Somehow, he escaped and fled to Tahiti, where he lived in poverty as a refugee, vowing to return to Raiatea someday to restore his family’s honor and reclaim his property.

In 1767, when the English navigator Samuel Wallis became the first European to land in Tahiti, the teenaged Mai was there to witness his arrival. Wallis declared the tropical paradise King George III Island and claimed it for Great Britain. Predictably, hostilities soon erupted. Wallis fired his guns at a promontory overlooking Matavai Bay, raining shrapnel and grapeshot on a crowd of angry onlookers. Mai was one of the many injured. A piece of metal sliced through his side, causing a nasty wound that left a jagged scar; for the rest of his life, his body gave literal testimony to first contact between the British and Tahitians. But the awesome power of the cannons made an equally significant impression on Mai’s imagination, and he began to fantasize that English guns, if he could obtain them, would provide the means to vanquish the Bora Borans and take back his land.

When Cook arrived in Tahiti in 1773, during his second Pacific voyage, Mai—now a headstrong young man of about 20—presented himself to the captain of the explorer’s consort ship, HMS Adventure, and begged to be taken to England. The captain, Tobias Furneaux, consented, and so Mai climbed aboard. It was a courageous leap of faith to join ranks with such utterly strange people, bound for an unfamiliar place so far away. He served as an able crewman on the official muster roll, earning regular pay, and he acquitted himself well. He could be a clown at times, silly and full of mischief, but Furneaux and his men liked him. Aboard ship, Mai learned some English and made many close friends. Some of his mates called him Omai or Omiah. (The “O” was something of a redundancy; in the Tahitian language, it means “here is” or “this is.”) Others called him Jack.

In October 1773, off the coast of New Zealand, the Adventure became separated from Cook’s vessel, HMS Resolution, in a storm. After searching in vain for Cook, Furneaux decided to head back to England. On July 14, 1774, the Adventure arrived at Portsmouth, England. On that sultry day, Mai became the first Polynesian to set foot on British soil.

Arriving with Mai in London, Furneaux placed him in the care of Joseph Banks, a noted botanist who had accompanied Cook on his first voyage and personally underwritten the scientific efforts of the expedition. It was decided that Banks would be Mai’s principal patron and chaperone during his time in England.

Not only did Banks have the wherewithal to properly host Mai; he had a fascination for Polynesia. But Banks was also eager to be Mai’s patron for another reason. As he was well aware, England had a long tradition of bringing people from far-off places back home for entertainment and study. For more than a century, explorers had brought back natives from the New World, Africa and Asia to see how they would fare in a European city. Perhaps most widely celebrated of all the arrivals was Pocahontas, the Powhatan woman from present-day Virginia who visited England in 1616 and was widely feted.

Banks had been hoping to have his own Indigenous companion for some time. In certain circles of London, much was made of the Polynesian societies Banks and Cook had encountered on their voyage. Across the South Pacific, the expedition had found unspoiled cultures, far removed from the corrupting influences of “civilization.” These graceful people appeared to be living in a state close to nature. Cook’s expedition heightened popular interest in questions that had been raised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Was man inherently good or evil? Was it possible that a primitive person could be nobler than a civilized one?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/d0/77d06de2-1bdb-4084-8067-0b76472d2eb3/omiah_the_indian_from_otaheite_presented_to_their_majesties_at_kew_by_mr_banks__dr_solander_july_17_1774.jpeg)

Banks briefly ensconced Mai at his house in London. The first order of business was to secure an audience with George III. The royal representatives at Kew promptly accepted Banks’s request. Now Mai had to prepare himself. A tailor would take his measurements. He would need to perfect his bow. Banks helped Mai learn a few English words, but because the Tahitian language was largely devoid of consonants, Mai struggled to form the sounds.

Finally, the day arrived. As Banks later recounted, Mai was smartly dressed in a new suit made of maroon Manchester velvet. He wore a white silk waistcoat and gray satin knee breeches. The king’s representatives ushered Banks and Mai into the chamber and presented them to the sovereign.

Mai greeted the king with a convincing bow but was so flustered that he forgot the salutations he and Banks had practiced. He grabbed the king’s arm with his tattooed hand, blurting, “How do, King Tosh?” Tosh was as close as he could get to pronouncing the name George.

The king presented Mai with a sword, and the Polynesian, regaining his composure, launched into a speech, in very broken English: “Sir, you are king of England, king of Tahiti. I am your subject, come here for gunpowder to destroy the people of Bora Bora, our enemy.”

George was interested in solidifying England’s hold over Tahiti and its surrounding islands, for he knew that the French and probably also the Spanish had designs on the lovely archipelago. But he had no interest in entangling the empire in interisland conflicts in the way Mai was advocating, so the king moved the conversation to other topics. He promised to return Mai to the South Pacific as soon as the next expedition could be mounted.

Following the royal audience, Banks took Mai on a grand tour of the estates of various noblemen and the salons of his intellectual friends. Everywhere Mai went, people were taken with his sweet disposition, impeccable manners and ready laugh. The country life agreed with Mai. He learned how to fire a fowling piece, how to catch fish in the local streams and how to ride a horse (although apparently not very well). He loved to roam the fens and moors, and he readily joined in horse races, games, picnics, concerts, dinner parties and tea parties.

His English was still crude, but he was improving. He was better at understanding the strange new language than speaking it. If he was slow in picking up the words, he soon mastered the inflections and intonations, the body language and facial expressions, of those around him.

Mai had “some special something,” historian Richard Connaughton told me, and he exerted a “powerful effect on people that’s difficult to explain. He had dark, piercing eyes, lovely teeth, and hair down to his shoulders. That’s where part of the charm came from. But there was something more—he had a sort of charisma. And he ticked all the boxes for what the noble savage was supposed to be. Certain people in England had been on a quest for the perfect person, the quintessential person, to represent this archetype, and here he was, made to order.”

Though a steel-nerved hunter, Mai could be acutely sensitive about other things. He became disturbed when he saw a worm wriggling on a fisherman’s hook. Apparently, in his home islands, a religious stricture forbade the harming of worms. As a friend described it, Mai “turned away from a sight so disagreeable, declaring his antipathy to eat any fish taken by so cruel a method.” At concerts and dramatic performances, he was quick to tear up. Funerals were so distressing to him that he couldn’t get through the service. He always took pity on beggars; the desperate poverty he encountered while visiting various English cities upset him.

During the dark winter days, Mai was often melancholy and homesick, and could sometimes be heard crying out as he wandered London’s cobblestone streets at night. He didn’t like the big city much, with its noise, its rank cesspools, and its coal soot dusting everything.

And yet the city very much liked him. Londoners were united in their opinion that Mai must be Tahitian royalty, and Mai continued to play along with the charade. In much the same spirit as the Joshua Reynolds painting, another notable London portraitist, Nathaniel Dance-Holland, captured Mai in a princely light, showing him holding a stool, traditionally carved from a single piece of wood, known as an iri. This was an overt symbol of aristocracy in Tahiti, where chiefs were at no time allowed to tread, sit or lie directly upon the ground.

All things considered, Banks was enormously pleased with how well Mai was assimilating into English society. The botanist was both surprised and enchanted by what he called Mai’s “gentility.” The experiment seemed to be working beautifully. “He succeeds most prodigiously,” Banks wrote to his sister. “So much natural politeness I never saw in any man: wherever he goes he makes friends and has not I believe as yet one foe.”

Others, however, were not so sure about the way Banks was running his anthropology experiment. Some critics thought he should place more emphasis on educating Mai, instead of parading him around like a show pony in posh social settings. Those of a more religious bent, meanwhile, worried that Mai’s soul had been neglected.

“I do not find that any steps have been taken toward giving him any useful knowledge,” carped one clergyman who encountered Mai. A Scotsman who met Mai predicted that the people of Tahiti would find his stories about life in England unbelievable. “This poor fellow, Omai … they have taught him nothing [and] he will only pass for a consummate liar when he returns, for how can he make them believe half the things he will tell them?”

Mai departed England on July 12, 1776, joining Cook and his crew aboard the Resolution. He settled on the island of Huahine, about 120 miles west of Tahiti, but struggled to reassimilate, clashing with locals over his exaggerated sense of superiority and the odd assortment of goods he’d brought back from England. Mai’s exact fate is unclear. Sources suggest he died just a few years after returning home, succumbing to a virus sometime in 1780.

Like so many cases of cross-cultural transplantation, Mai’s odyssey led him, in the end, to an ambiguous place. I’ve come to think of his journey as an allegory of colonialism and its unintended consequences: England, by showing off her riches and advancements and then sending Mai back with a trove of mostly meaningless treasures, had doomed him to a jumbled, deracinated existence. Like the tiare apetahi flower, Mai, for all his travels, couldn’t take root in other soils.

Adapted from The Exotic: Intrigue and Cultural Ruin in the Age of Imperialism by Hampton Sides. Copyright © 2021 by Hampton Sides. Available from Scribd Originals. Join Scribd here to read the full story on September 15.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/hampton.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/hampton.png)