The Preservation Battle of Grand Central

Forty years ago, preservationists—including a former First Lady—fought to maintain the integrity of New York City’s historic railway station

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/c7/00c70264-3d1b-4cb4-b510-f8d8d486d9d1/photo_1.jpg)

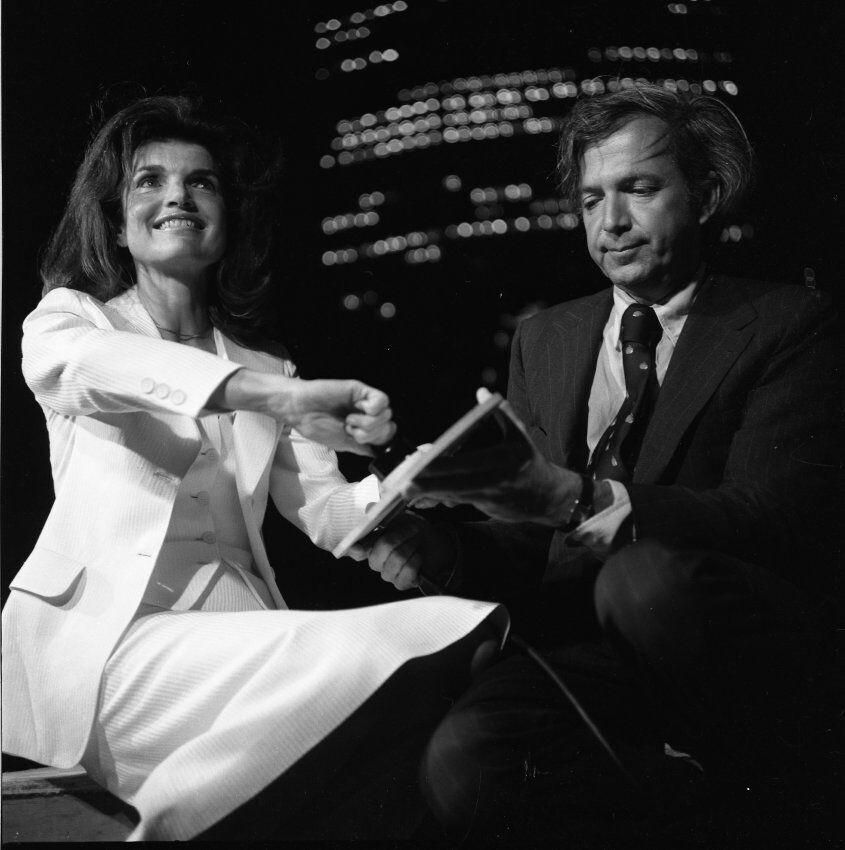

"If we don’t care about our past we can’t have very much hope for our future,” Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis intoned at a press conference held at Grand Central Terminal’s famous Oyster Bar in 1975. "We’ve all heard that it's too late, or that it has to happen, that it's inevitable. But I don’t think that's true,” said the New York resident and native. “Because I think if there is a great effort, even if it’s the eleventh hour, then you can succeed and I know that’s what we'll do.”

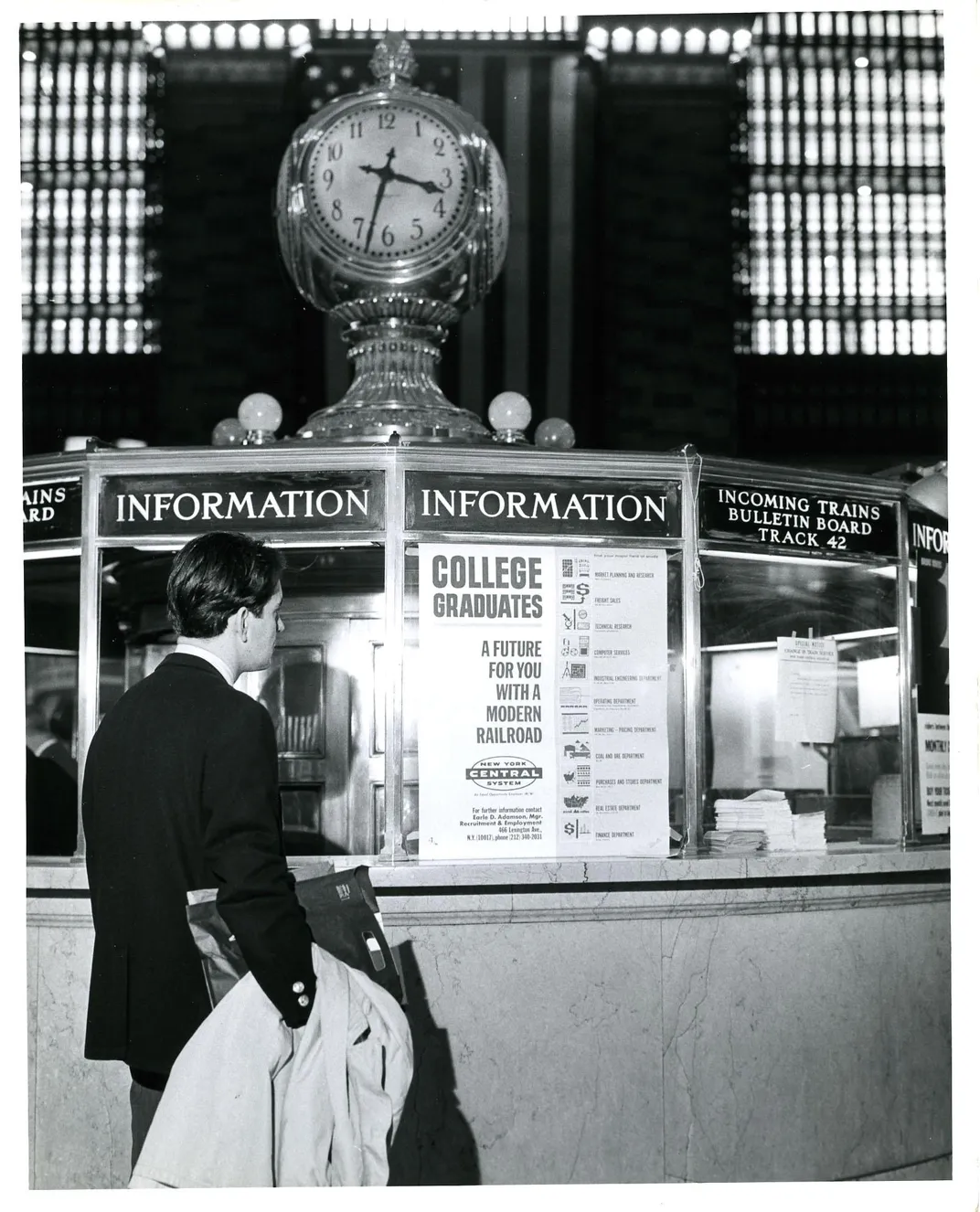

The former First Lady was there to illuminate the plight of the Beaux Arts railway station that once dazzled New Yorkers and was, upon its opening in 1913, considered one of the city’s greatest wonders. Intended by developers to dwarf the nearby Penn Station, Grand Central Terminal cost nearly $160,000,000 (more than $4 billion today) to construct and was a front-page story in the local papers for weeks leading up to opening day. As dependence on rail travel diminished in the mid-20th century, Grand Central’s relevance too was questioned, and in 1963, the top of the station became the base for the tower known as the Pan-Am building, named after the airline headquartered there.

In 1975 a plot was hatched to dwarf the Pan-Am building with an even larger structure designed by famed Modern architect Marcel Breuer, but there was a problem: the sting of Penn Station’s demolition in 1964 was still fresh in the minds of many New Yorkers. In the aftermath of that legendary building’s destruction, Grand Central had been designated a New York City Landmark under a new law that gave the city the power to protect buildings it deemed worthy. When plans for the Breuer addition were presented to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the response from officials was that the tower was essentially an “aesthetic joke.”

While few doubted the significance of Grand Central, the terminal’s owners took issue with the law itself—how, they wondered, could it constitute anything other than an unreasonable violation of their rights as property owners? Preservationists like Onassis, working with groups like the Municipal Art Society, continued to insist that saving Grand Central and buildings like it wasn’t a mere real estate matter, but an issue of public good. On June 26, 1978, the United States Supreme Court agreed with them in Penn Central Transportation Co. vs. New York City, not just in regards to Grand Central but in the spirit of the Landmarks law itself, with Justice William Brennan writing that to rule in favor of the building’s owners would “invalidate not just New You City’s law, but all comparable landmark legislation elsewhere in the nation.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/58/485832a3-2d5c-4ce5-9862-fea5347dd963/image_3.jpg)

Forty years after the decision, Grand Central is still a jewel of Manhattan architecture and a vibrant destination in its own right. Nearly 750,000 travelers pass through the building each day, and a series of more recent renovations have strived to keep the space usable while maintaining the grandeur and light so key to the original design that so enchanted the public.

For preservationists, the story of Grand Central is one of triumph, and the challenges of holding onto historic structures in ever-changing cities ultimately haven’t changed much. “Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud moments, until there is nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children,” wondered Onassis in a 1975 letter to then-Mayor Abraham Beame, an attempt to galvanize the mayor into challenging the new Grand Central plan? “If they are not inspired by the past of our city, where will they find the strength to fight for her future?”

Editors' Note, June 27, 2018: This story originally included photographs of the Grand Central Depot, not Grand Central Terminal. Those photos have been removed from the article.