Preserving the World’s Most Important Artifacts

The Memory of World Register lists over 800 historic manuscripts, maps, films and more to help raise funds for preservation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Tripitaka-Koreana-UNESCO-World-Register-631.jpg)

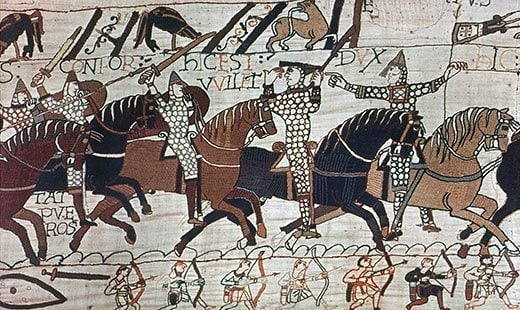

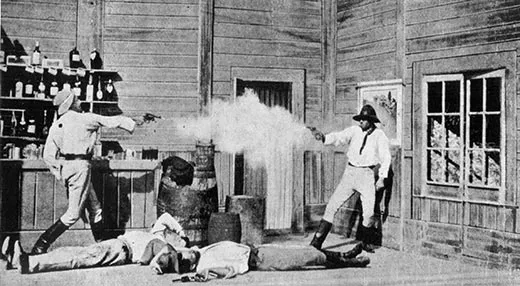

What would you call a list that includes the 11th-century Bayeaux tapestries and the proceedings of the trial of Nelson Mandela? Plus Story of the Kelly Gang, the world's first feature-length film, made in 1906, and Iran’s 10th-century Book of Kings, considered Persia’s Iliad? And even Grimm’s fairy tales, Alfred Nobel’s family archives and the 13th-century Tripitaka Koreana, 81,258 wooden blocks thought to be the world’s most complete collection of Buddhist texts?

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which keeps such a list, calls it the Memory of the World Register. And the list will get longer this August.

U.N. agency had little money for preservation, it decided to safeguard as much as it could by naming manuscripts, maps, films, textiles, sound files and other historical documents and artifacts to the register.

“We raise awareness of the importance of these collections,” says Joie Springer, the senior program officer for the Memory of the World Register. “It’s a seal of approval, enabling them to raise funds for preservation and raise the profile of the institution that owns the collection.”

In many ways, the Memory of the World Register mimics UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites roster, which currently lists 878 cultural or natural places around the globe. Designation as a heritage site bestows cachet and often turns historically significant places into tourist attractions; a listing on the Register could have a parallel impact.

But the Memory of the World Register, which totals 158 items, is 20 years younger than the sites program and less well known. Documentary treasures usually can’t be visited by tourists, and they tend to appeal to a narrower, better educated public. Even some high-ranking professionals—such as Geoffrey Harpham, director of the National Humanities Center, and Bruce Cole, who until recently was chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities—have never heard of the register, though both say they think it’s a great idea. “The historical imagination of any culture has to be founded on facts,” says Harpham. “Anything that helps bring those facts to the attention of the public is a valuable thing.”

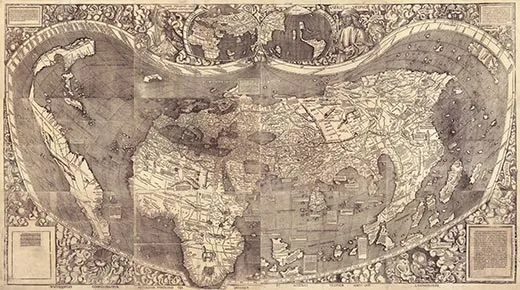

UNESCO would like the program to be better known, too, Springer says; it is now taking a survey to determine who knows about the register and how a listing has helped objects on it. But she also notes that it may lack prominence here because the United States withdrew from UNESCO in 1984, re-joining only in 2002. The U.S. has just two listings on the register: The Wizard of Oz, submitted by the George Eastman House, and the 1507 World map by Martin Waldseemüller, the first to name the New World “America.” It was submitted by the Library of Congress, which owns the only surviving copy, and the mapmaker’s native Germany.

The Register is expanded in odd-numbered years. In each round, each UNESCO member (193 at the moment) may make up to two nominations. (And if they submit joint-proposals with another country, there is no limit.)

In July, a 14-member advisory committee will meet in Barbados to assess 55 nominations. Springer says those deliberations don’t take long: the applications have to be filed by March of the previous year, and undergo a long review by experts from around the world. UNESCO plans to announce this year’s designees in early August.

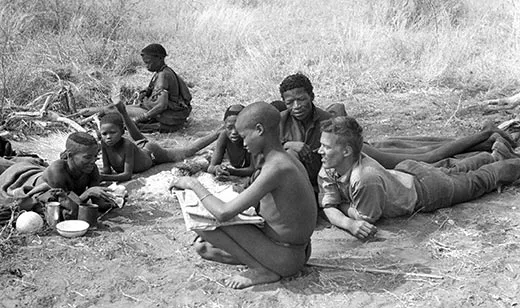

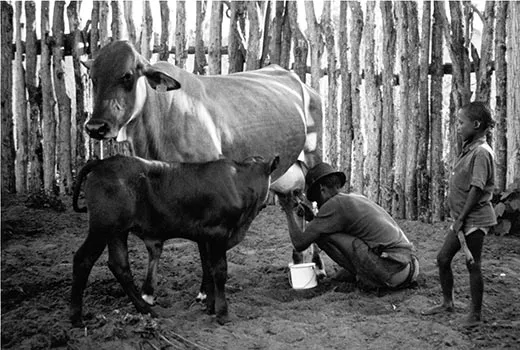

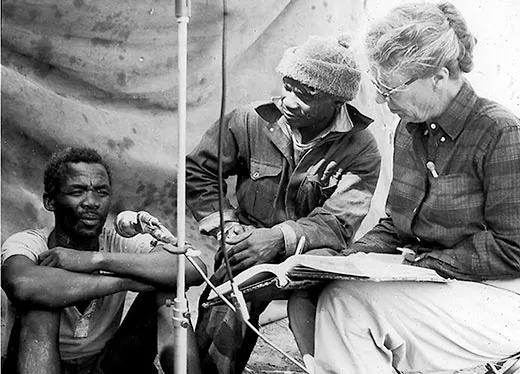

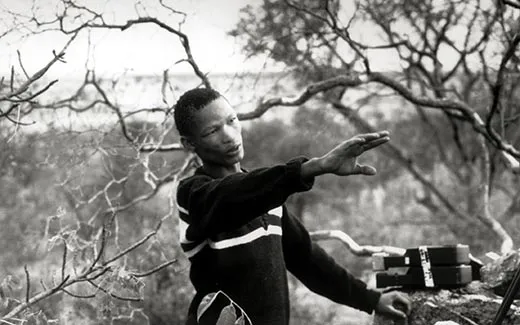

The sole U.S. nominee this year is from the Smithsonian Institution: the John Marshall Ju/'hoan Bushman Film and Video Collection, 1950-2000, located in the Human Studies Film Archives. Pamela Wintle, senior archivist there, made the submission. A longtime advocate of film preservation, she learned of the register when The Wizard of Oz was chosen in 2007, and immediately thought of the Marshall collection. “It was filmed over a 50-year period during which an indigenous group went through extraordinary development from the Stone Age to the 20th century,” she says. “It’s an amazing story.”

The official nomination describes the collection as “one of the seminal visual anthropology projects of the twentieth century. It is unique in the world for the scope of its sustained audiovisual documentation of one cultural group, the Ju/'hoansi, of the Kalahari Desert, in northeastern Namibia.”

Other nominees this year are an encyclopedia of Eastern medicine, compiled in Korea in 1613; the “Woodblocks of Nguyen Dynasty,” which help to record official literature and history of the family that ruled Vietnam from 1802 through 1945; a sound collection of Mexico’s indigenous languages, traditions, celebrations, rituals, ceremonies and music; an archive documenting the ecological catastrophe following the damming of Aral Sea tributaries, and the Anchi Gospel, a masterpiece written in Nuskhuri, an old Georgian script, made partly in a red ink unique to Georgia.

Fortunately for the panel, there’s no limit on the number they can select: it’s all based on “world significance.” That’s fortunate, too, for the world.