The Prince Who Preordered Jane Austen’s First Novel

The future George IV was a big fan of the author, a feeling she half-heartedly reciprocated with a dedication years later

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/f6/62f6453b-8511-4f4a-9e8d-0d2a6eea282a/upper_library_view_2.jpg)

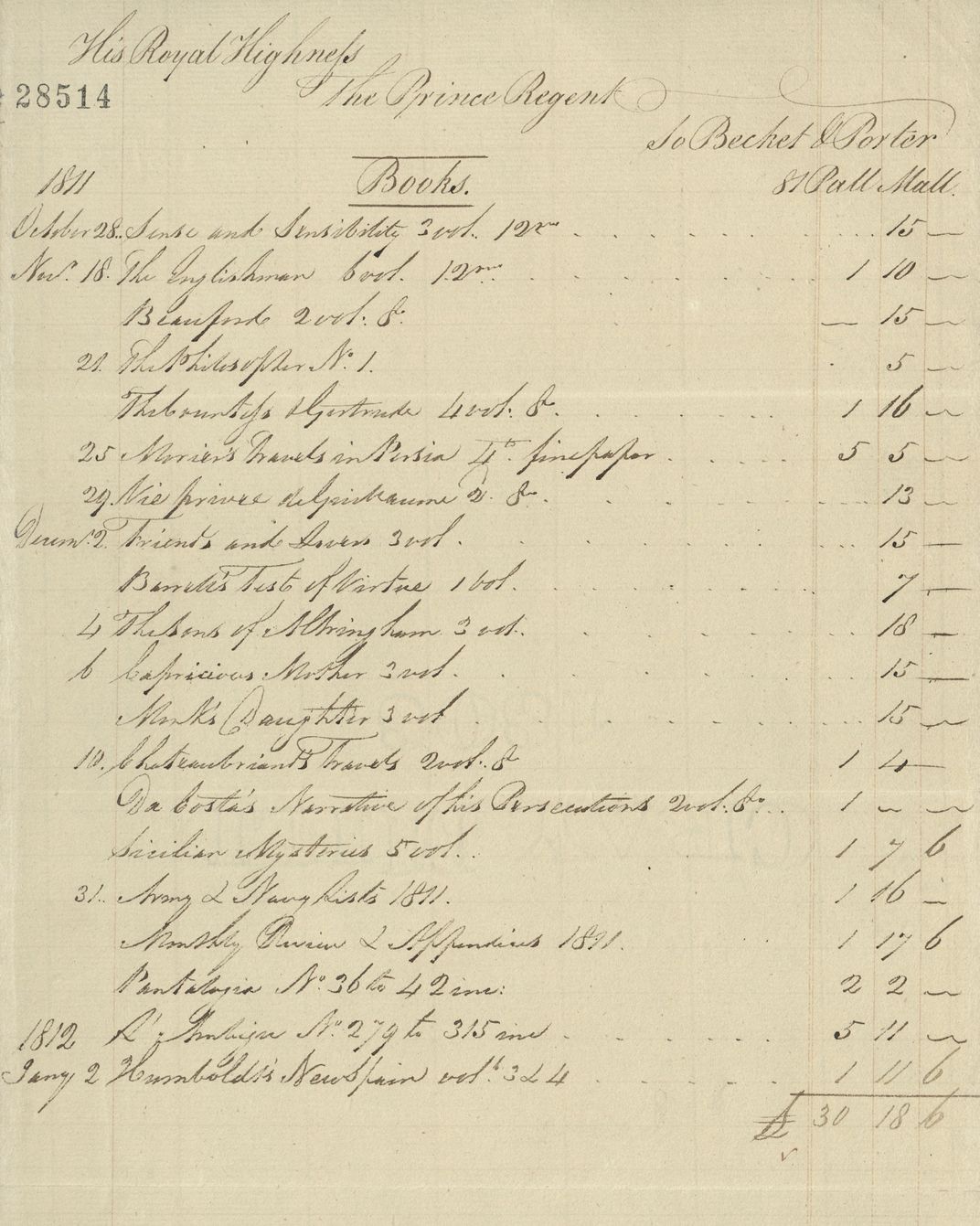

For an author publishing her first novel, every pre-order is a valuable prize. For Jane Austen, a 36-year-old writer who polished her prose in a country parlor by reading aloud to family, cracking 19th-century England’s book market came with some royal help. A new discovery —a 15-shilling bill of sale from 1811, for Austen’s Sense and Sensibility two days before it was publicly advertised, and made out to the prince regent (later George IV)—made via the Georgian Papers Programme sheds light on Austen’s popularity and the prince’s cultural power.

“As the first documented purchase of an Austen novel, it raises all sorts of delicious speculations, not to mention some entertaining irony,” says historian Sarah Glosson. “The prince, while reviled by many, would have been a tastemaker in his social circle, so the fact that he likely had one of the very first copies of Sense and Sensibility—perhaps in his hands before anyone else—is remarkable.”

George, who ruled as prince regent from 1811 due to his father George III’s illness, ascended the throne in 1820 and was passionate about collecting books, artworks, and furniture in great quantity. Caricaturists in the popular press painted George as luxury-loving and self-indulgent, but the prince regent struck back strategically. He became a co-proprietor of London’s Morning Post, in a bid to steer media coverage. He bought up unflattering prints and tried to quash salacious material with legal action.

His media consumption went far beyond that; the prince regent’s vast appetite for literature ran to contemporary works and military history, “which was the only subject area in which he spent extensively at auction,” said Emma Stuart, senior curator of books and manuscripts in the Royal Library. “As far as is currently known, the vast majority of his fiction was purchased, rather than presented, through his booksellers/agents, the chief of whom were Becket & Porter, and Budd & Calkin.”

George IV left a well-documented (and soon-to-be-digitized) trail of debt, numbering about 1,800 bills at Windsor Castle alone that invite scholars to travel back into Jane Austen’s day. As University of Pennsylvania doctoral student Nicholas Foretek combed through a box of the prince regent’s bills at the Royal Library and Archives, he came across a October 28, 1811, bill from one of George’s favorite firms, Becket & Porter.

Austen’s name, familiar to many as a colorful and crisp novelist of early 19th-century life and manners, caught Foretek’s eye. “A couple days later, I returned to the bill and looked into the publication history of Sense and Sensibility,” Foretek said. “That was when it occurred to me that this was at least a very early purchase record. It took some more digging into the rather grand annals of Austen literature to figure out it was the earliest such bill.”

How did a debut novel by a parson’s daughter snag the attention of a profligate prince? Displaying the same ingenuity and intelligence evident in her heroines, Austen staked out a plan to see her work in print. She paid publisher Thomas Egerton, who normally listed military titles, to handle the sales and distribution of her double love story about the Dashwood sisters. When Austen’s book came to market, her name was nowhere on the title page. In keeping with literary custom at the time, Sense and Sensibility was written “By A Lady.” While Austen wended her way through the publishing world, often with her brother Henry’s aid, the prince regent socialized with writers like Sir Walter Scott and Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

As with many bestsellers of the time, it was a chain of personal connections that likely closed the sale. In Austen’s England, the “distinctions between printers, publishers and booksellers were more fluid than they are now,” says Oliver Walton, Georgian Papers Programme coordinator and curator, Historical Papers Projects, at the Royal Library. In the fall of 1811, the Regency publishing industry was a tightly knit realm. “Egerton knew [bookseller] Becket. Becket knew the Prince. So a self-published work of fiction by a parson’s daughter can end up being charged to a prince in short order upon its having been printed because the business relationships were localized and the community wasn’t huge,” Foretek adds.

Jane Austen, in turn, knew the prince by reputation. Joining in public disapproval of his extravagant lifestyle, she nurtured a hearty dislike for George IV. Yet Austen grudgingly dedicated her novel Emma (1815) to him, when invited to do so. Foretek’s find, meanwhile, has yielded a new mystery: the location of the prince’s copy of Sense and Sensibility.

Windsor archivists report that it has long since left the shelf. “The Royal Library team has analyzed the historic inventories and found evidence that it had been in Brighton in the 1820s, but that by the 1860s it was gone, with its inventory entry struck through,” Walton said. Somewhere in the world, perhaps, George IV’s Sense and Sensibility awaits rediscovery.

Since Elizabeth II launched the digitization project in April 2015, researchers like Foretek have unearthed surprising links between the Georgian court and Anglo-American culture. To transcribe and share the archive, Windsor scholars have joined with the Royal Collection Trust and King’s College London. The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the College of William & Mary serve as the primary U.S. partners for the project, and have sponsored research fellows to study the archive. (You can apply here.)

Mount Vernon, the Sons of the American Revolution, and the Library of Congress have also announced their participation. Researchers can conquer the manuscript trove of the Round Tower from afar. More than 60,000 pages of material are available to read in the online portal, with another 20,000 pages coming soon, Walton said. A major exhibition with the Library of Congress, slated to open in Washington, D.C., in 2020, will present the “Two Georges,” George III and George Washington.

Piecing together royal receipts, stray bills, and lost books can add up to a deeper view of the public and private connections that bonded together the Anglo-American world, says historian Karin Wulf, director of the Omohundro Institute. “Using these different forms of evidence gets us closer to daily life for a lot of people. In this case a bill of sale for Sense and Sensibility adds to the long-known information that Austen was told of the prince regent’s admiration and encouraged to dedicate a book, which would have been seen as a huge mark of royal favor, by showing us that he had the very first of her publications. But it also shows us how that sale connected the publisher and the librarian acquiring the book. We can imagine the volumes in the library being dusted. And we are reminded of the many women in these households who might have been Austen readers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)