Print the News, Right In Your Home!

Decades before the Internet, radio-delivered newspaper machines pioneered the business of electronic publishing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201204170210441938-newspaper-fax-470x251.jpg)

The introduction of broadcast radio caused some in the newspaper industry to fear that newspapers would soon become a thing of the past. After all, who would read the news when you could just turn on the radio for real-time updates?

Newspapers had even more to fear in 1938 when radio thought it might compete with them in the deadtree business as well.

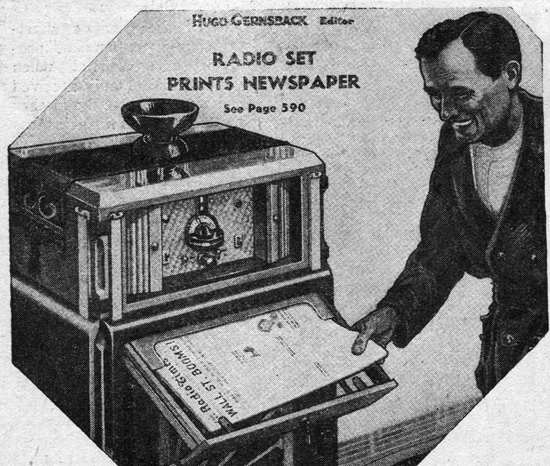

The May, 1938 issue of Hugo Gernsback‘s Short Wave and Television magazine included an article titled “Radio to Print News Right In Your Home.” The article described a method of delivering newspapers that was being tested and (provided it didn’t interfere with regular radio broadcasts) would soon be used as a futuristic news-delivery method.

The magazine proudly included a previous prediction from a different Gernsback publication four years earlier, before the FCC had granted trials:

Hugo Gernsback, in the April 1934 issue of Radio-Craft forecast the advent of the “radio newspaper.” Here’s the front cover illustration of that magazine. Compare it with the pictures on the opposite page!

Cover of the April, 1934 issue of Radio-Craft magazine

The article opens by explaining that this futuristic device is already in use:

As you read this article, radio facsimile signals are probably circulating all around you. At least 23 broadcast stations, some of them high power ones, and a number of short-wave stations are now transmitting experimental facsimile signals under a special license granted by the Federal Communications Commission.

This invention of a wireless fax, as it were, was credited to W.G. H. Finch and used radio spectrum that was otherwise unused during the late-night hours when most Americans were sleeping. The FCC granted a special license for these transmissions to occur between midnight and 6am, though it would seem that a noisy printing device in your house cranking away in the middle of the night might have been the fatal flaw in their system. It wasn’t exactly a fast delivery either, as the article notes that it takes “a few hours” for the machine to produce your wireless fax newspaper.

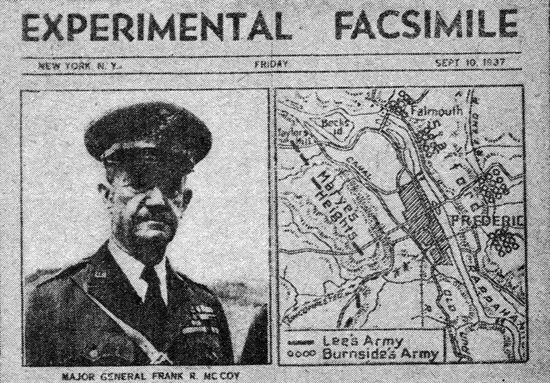

An RCA facsimile receiver, printing that day's newspaper

The article explained exactly how the process worked:

The photo or other piece of copy, such as news bulletins, is placed in the scanner at the transmitter. At the rate of 100 lines per inch picture to be transmitted is scanned, and the transmitter sends out periodic impulses which vary in strength with the degree of light or shade on the picture. When these signals are received, by wire or radio, they are passed into a recording stylus. This stylus moves back and forth over a piece of chemically dry processed paper (the Finch system) in a line, wide or narrow as the case may be, is traced on the paper. A facsimile such as that shown in one of the accompanying pictures is obtained, and it thus becomes an easy matter to reproduce printed matter, drawings and photos, etc.

100-line experimental reproduction of the RCA process

The article mentions two parties that are experimenting with the technology (Mr. Finch and RCA) but goes on to explain that nothing about the system had been standardized yet.

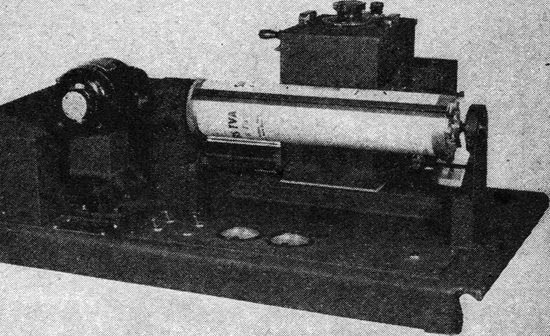

Many different systems of transmitting and recording devices by facsimile have been tried. The one used by the Finch system employs a special chemically treated paper. When a current passes through the moving stylus needle, the reaction causes a black spot to appear on the paper, the size of the spot at a given point depending upon the strength of the received impulse. At the transmitter the light beam is focused on the picture to be sent and the reflected light falls on a photo-electric cell.

The RCA transmitter-scanner with pictures and text placed directly on the scanning drum

Whether Finch and RCA knew it or not, battles between formats would continue right on into the 21st century as the fight over newspaper paywalls, cord-cutters, and ebooks continues to dramatically shift our media landscape.

W.G.H. Finch, the inventor of the radio facsimile system

Mr. Finch (pictured above) would later invent the first color fax machine in 1946. You can watch video of his radio-fax machine in action at Getty Images.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)