Prohibition’s Premier Hooch Hounds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Past-Imperfect-disguise-prohibition.jpg)

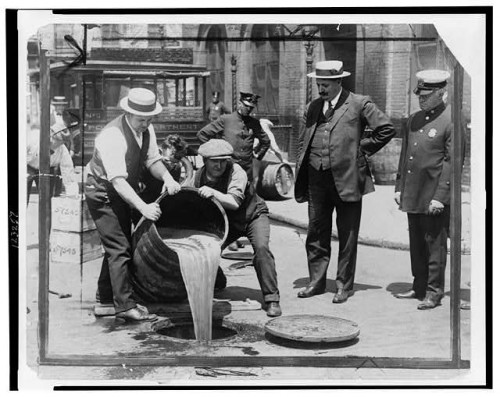

As midnight approached on January 16, 1920, New York was in the throes of a citywide wake. Black-bordered invitations had been dispensed weeks before, announcing “Last rites and ceremonies attending the departure of our spirited friend, John Barleycorn.” The icy streets did little to deter the “mourning parties,” which began at dinnertime and multiplied as the hours advanced.

On the eve of Prohibition, guests paid their respects at the Waldorf-Astoria, hip flasks peeking from waistbands, champagne glasses kissing in farewell toasts. Park Avenue women in cloche hats and ermine coats gripped bottles of wine with one hand and wiped real tears with the other. Uptown at Healy’s, patrons tossed empty glasses into a silk-lined casket, and eight black-clad waiters at Maxim’s hauled a coffin to the center of the dance floor. Reporters on deadline tapped out eulogies for John Barleycorn and imagined his final words. “I’ve had more friends in private and more foes in public,” quoted the Daily News, “than any other man in America.”

One of alcohol’s most formidable (and unlikely) foes was Isidor Einstein, a 40-year-old pushcart peddler and a postal clerk on the Lower East Side. After Prohibition took effect, he applied for a job as an enforcement agent at the Southern New York division headquarters of the Federal Prohibition Bureau. The pay was $40 a week, and to Izzy it seemed “a good chance for a fellow with ambition.” Chief Agent James Shelvin assessed Izzy, who stood 5-foot-5 and weighed 225 pounds, and concluded he “wasn’t the type,” but Izzy argued that there was an advantage to not looking the part—he could “fool people better.” And although he lacked experience with detective work, he said, he knew “something about people—their ways and habits—how to mix with them and gain their confidence.” He would never be spotted as a sleuth. As a bonus, the Austrian-born Izzy spoke six languages, including Polish, German, Hungarian and Yiddish. He got the job.

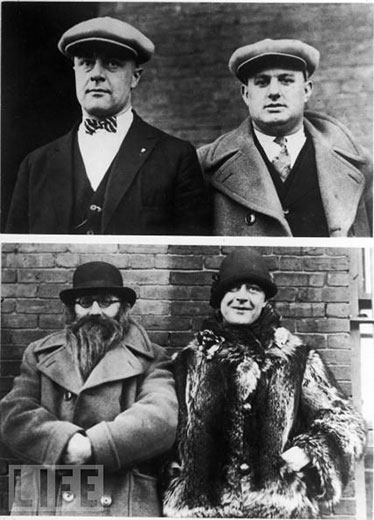

Portrait of Prohibition-era policemen Moe Smith and Izzy Einstein. Photo courtesy of Time Life Pictures / Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images.

(See more stunning Prohibition-era photos from LIFE magazine: When Booze Ruled and How Dry we Ain’t.)

One of Izzy’s first assignments was to bust a Manhattan speakeasy that had a reputation for spotting revenue agents. With his badge affixed to his coat, he asked the proprietor, “Would you like to sell a pint of whiskey to a deserving Prohibition agent?”?

The bar owner laughed and served him a drink. “That’s some badge you’ve got there,” he said. “Where’d ya get it?”

“I’ll take you to the place it came from,” Izzy replied, and escorted the man to the station.

Izzy asked his boss if his friend Moe Smith, the owner of a cigar store, could have a job, his main qualification being that “he doesn’t look like an agent, either.” Moe was a couple of inches taller and nearly 50 pounds heavier than Izzy, and in spite of their size—or perhaps because of it—they proved ideal for undercover work, creating personas and honing disguises, each subterfuge more elaborate than the last.

Their cache of accessories included dozens of false whiskers, nine kinds of eyeglasses, six papier-mâché noses (none of which, one newspaper noted, matched the distinguished form of Izzy’s own), eleven wigs and hundreds of business cards, each presenting a different name and occupation. They believed that props—a string of fish, a pitcher of milk, trombones, a fishing rod, a big pail of pickles—were essential to success. “My carrying something seemed to OK me,” Izzy explained. Their most ingenious invention was an “artificial gullet”—a surreptitious drainage system that allowed Izzy to collect evidence without drinking it. This consisted of a rubber bag beneath his shirt that was connected by a rubber tube to a glass funnel sewn into his vest pocket. He would take a sip of liquor and discreetly pour the rest down the funnel.

As Izzy and Moe began their careers, New York City’s illegal liquor trade was becoming the largest operation in the country, with an estimated 32,000 speakeasies sprouting in unexpected places: tucked behind receptionists’ desks in office buildings; amid the rubble and machinery of construction sites; in the cellars of fashionable millineries and the back rooms of stately town homes; across from police stations; at the top of the Chrysler Building. Revelers bet one another who could find the oddest location for their next libation.

Bootleggers transported product via an intricate system of underground pipes, including a 6,000-foot beer pipeline that ran through the Yonkers sewer system. Proprietors of cordial shops nailed signs that read “importer” or “broker” on their doors, a clear signal that they were in the know. They also slipped flyers under windshields and apartment doors, offered free samples and home delivery, took telephone orders and urged customers to “ask for anything you may not find” on the menu. Drinking now required cunning, urbane wit, the code to a secret language. “Give me a ginger ale,” a patron said, and waited for the bartender’s wink and knowing reply: “Imported or domestic?” The correct answer—imported—brought a highball.

Izzy and Moe proved just as savvy as their targets, busting an average of 100 joints per week, Moe always playing the straight man to Izzy’s clown. One night the duo, dressed as tuxedo-clad violinists, sauntered into a Manhattan cabaret, sat down and asked a waiter for some “real stuff.” The waiter consulted with the proprietor, who thought he recognized the musicians as performers from a nightclub down the street.

“Hello, Jake,” he called to Izzy. “Glad to see you. Enjoyed your music many a time.” He told the waiter to serve the musicians anything they wanted.

Moments later, the proprietor approached their table and asked if they might play “something by Strauss” for the room.

“No,” Izzy replied, “but I’ll play you the ‘Revenue Agent’s March.’” He flashed his badge, and the proprietor suffered a heart attack on the spot.

When they heard about a Harlem speakeasy at 132nd Street and Lenox Avenue, in the heart of New York City’s “Black Belt,” they knew that any white costumer would have little chance of being served. So Izzy and Moe would apply blackface and drop in from time to time to get a feel for the place, learning its unstated rules and specific jargon: a “can of beans” was code for a half pint of whiskey, and “tomatoes” meant gin. On their last visit they brought a warrant and a truck, confiscating 15-gallon kegs of “beans” and 100 small bottles of “tomatoes” hidden in a pickle barrel.

Prohibition allowed for rare exceptions, most notably in the case of religious or medicinal alcohol, and bootleggers took full advantage of the loopholes. Section 6 of the Volstead Act allotted Jewish families 10 gallons of kosher wine a year for religious use. (Unlike the Catholic Church, which received a similar dispensation, the rabbinate had no fixed hierarchy to monitor distribution.) In 1924, the Bureau of Prohibition distributed 2,944,764 gallons of wine, an amount that caused Izzy to marvel at the “remarkable increase in the thirst for religion.” Izzy and Moe arrested 180 rabbis, encountering trouble with only one of them. The owner of a “sacramental” place on West 49th Street refused to sell to the agents because they “didn’t look Jewish enough.” Undeterred, and hoping to prove a point, Izzy and Moe sent in a fellow agent by the name of Dennis J. Donovan. “They served him,” Izzy recalled, “and Izzy Einstein made the arrest.”

They dressed as grave diggers, farmers, statues, football players, potato peddlers, operagoers, cowboys, judges, bums, old Italian matrons and, as the Brooklyn Eagle put it, “as chunks of ice or breaths of air or unconfirmed rumors,” but Izzy scored one of his favorite coups wearing no disguise at all. During a visit to a saloon in Brooklyn, the agent noticed a large photograph of himself on the wall, accompanied by several stories about his raids. He stood directly beneath the display and waited, futilely, for someone to recognize him. “Finally,” he said, “I pulled out a search warrant and had to laugh at the faces of the people.”

From 1920 to 1925, Izzy and Moe confiscated about five million bottles of illicit liquor, arrested 4,932 people and boasted a conviction rate of 95 percent. They refused to take bribes, and Izzy never carried a gun, preferring to rely only on “the name of the law.” Ultimately, the agents were victims of their own success; superiors grew to resent their headlines, and other agents complained that their productivity made their own records look bad. According to Izzy, one Washington official scolded, “You are merely a subordinate—not the whole show.” In November 1925, Izzy and Moe were among 35 agents to be dropped from the force. “Izzy and Moe,” quipped the Chicago Tribune, “are now disguised as cans.”

In 1932, the year before Prohibition ended, Izzy published a memoir, Prohibition Agent #1. He avoided mentioning Moe Smith by name, explaining that his former partner didn’t want to be known as “Prohibition Agent #2.” At a press conference he admitted to taking the occasional drink, “sacramental wine” being his favorite, and invited reporters to ask him questions.

“What are your convictions, Mr. Einstein?” one inquired. “Do you believe in the moral principle of Prohibition?”

For once, Izzy was at a loss for words. “I don’t get you,” he said finally, and the press conference was over.

Sources:

Books: Isidor Einstein, Prohibition Agent #1. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1932; Karen Abbott, American Rose. New York: Random House, 2010; Michael A. Lerner, Dry Manhattan. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Articles: “Izzy and Moe End Careers as Dry Agents.” New York Times, November 25, 1925; “Izzy and Moe.” American History, February 2001; “Saga of Izzy Einstein.” The Washington Post, June 27, 1935; “Izzy and Moe Is No Mo’.” Los Angeles Times, November 14, 1925; “Moe and Izzy of Dry Mop Fame Fired.” Chicago Tribune, November 14, 1925; “Face on Barroom Wall Was Izzy’s.” New York Times, June 27, 1922; “Izzy is Orthodox, So He Knows Vermouth Isn’t Kosher Wine.” New York Tribune, July 15, 1922; “Rumhounds Izzy and Moe.” New York Daily News, December 23, 2001. “Izzy and Moe: Their Act Was Good One Before It Flopped.” Boston Globe, November 22, 1925.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)