I didn’t leave Puerto Rico until I was 20. I was traveling to Europe with my college theater group when an immigration official in Spain said, “Oh, you’re American.” I tried to tell them, “Yes—but no.” I tried to explain that I am an American citizen in a place that “belongs to...but is not a part of” the United States, according to the Supreme Court’s definition of an unincorporated territory.

Later that year, I had the opposite experience when I transferred to a photography school in Ventura, California. I was the only Puerto Rican in my class and I felt very much like a foreigner. Our culture is a mixture of European, African and Taíno Indian. We’re very warm and outgoing. I had to adapt to a very different chemistry with the other students in California. Some of my closer friends there were Mexican, but I had to use a more neutral Spanish when I spoke to them, without all my Caribbean slang. When I’d call home, my cousin would ask, “Why are you speaking so strangely?” I’d say, “I can’t speak Puerto Rican here!”

Staying Strong: Diary of a Hurricane Maria Survivor in Puerto Rico

September 20, 2017 changed Sandra’s life forever. She survived category five Hurricane Maria at her home in Puerto Rico, but for the following three months she has to use every ounce of creativity, patience and perseverance to survive without power, water or access to most basic services.

Once we graduated, my Latin American friends had to leave the country. That was strange for me—that they couldn’t stay and I could. Yet I knew the history of Puerto Rico and what that advantage had cost us.

In 1898, Puerto Rico was acquired by the United States as a “spoil” of the Spanish-American War along with Guam and the Philippines. Until 1948, all our governors were appointed by the U.S. government. Until 1957, our patriotic songs and other expressions of nationalism were outlawed. Even today, our government exists under the discretion of Congress—though we do not have a voting representative in that body. Since 1967, there have been five referendums in Puerto Rico on statehood, independence or maintaining the commonwealth, but all have been nonbinding.

So we exist in a confusing, kind of gray realm. We use U.S. dollars and U.S. postage stamps. We serve in the U.S. military and our borders are monitored by U.S. Customs. In my California student days, I’d give my phone number to friends and they would ask if it was an international call. I had to check with my telephone company to find out (it isn’t). That’s Puerto Rico.

I’ve been documenting this ambiguity for the past six years, starting with an internship at a Puerto Rican newspaper. I began photographing everyday moments: a salsa class at a bar, Mother’s Day with my family, festivals and political events. I could be at a rally, where everyone was shouting. But the best photo would be the one where a woman holding a sign was looking down and being introspective. You could feel her withdrawing into her own thoughts.

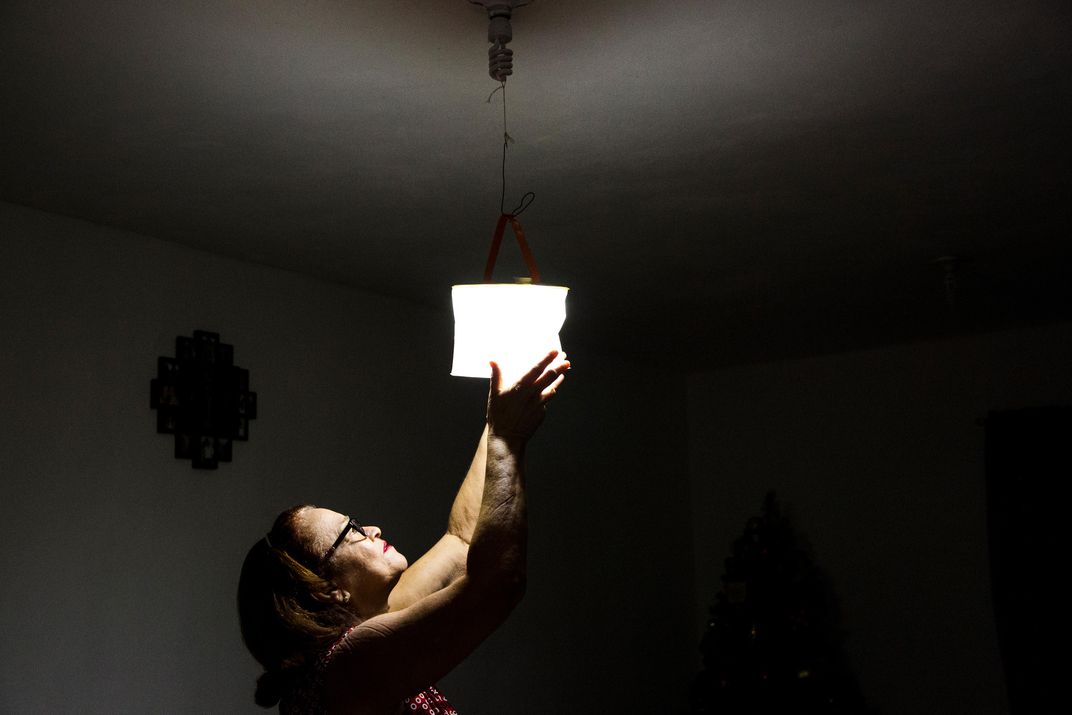

After Hurricane Maria ravaged everything in its path last year, there was a sense of unity among people of the archipelago. Under complete darkness, without sufficient fuel, water or food, and largely without communications, our sense of community changed. It was visible in the young neighbor who collected and distributed water for months after the storm, and in the person with a power generator who would provide electricity to other families through extension cords crossing from one home to another. It was visible in the neighbors who cooked together on the only working gas stove on their street. Tension and despair were real, but a new solidarity emerged.

Over a week after the storm, I spotted a Puerto Rican flag flapping on the side of a fuel truck. More soon appeared on car antennas, storefronts, home balconies, highway bridges and street corners. Our flag, once illegal, could now be seen all over the island. It was a message: “We are here and we are standing.”

But we’re still dealing with the aftermath. In San Juan, where I live, I regularly still see broken electrical posts, missing traffic lights and blue plastic tarps covering damaged rooftops. The power still goes out short term. Things are much worse in the mountain town of Utuado. Communities there have been without power since the hurricane, unable to store food in their refrigerators, and many roads remain exactly as they were back in September. Electrical cables hang overhead and vegetation now grows in the mudslides that cover entire lanes.

The phrase “Se fue pa’ afuera”—literally, “he went outside”—is an expression for a Puerto Rican who has left the island on a one-way flight. It has become far too common. I’ve been to many tearful goodbye parties. My sister left for Chicago and has no desire to ever return; I was introduced to my newborn godson over Skype. I continue to see friends find better possibilities outside.

We won’t know until the 2020 census how many people have already left. Since the beginning of the recession in 2006, Puerto Rico has lost around 635,000 residents, and another half million are expected to leave by next year.

As a young Puerto Rican, I’m unsure what lies ahead. That’s why I want to stay and continue documenting our complex dual identity. I want to photograph Puerto Rico as we rebuild, or fall apart. I just can’t look away. There’s no room in my mind or heart for anything else.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/8d/d58d56f5-cc66-440f-8e47-5267c78f2874/kulaug2018_m08_photorodriguez.jpg)