Syria’s civil war was hurtling into its third brutal year in the spring of 2014. Rakan Alzahab was 17. One day, when he was stopped at an army checkpoint near Damascus, a soldier examined his cellphone. Among the pictures on it was one of his cousin’s daughter holding a rebel group’s flag across her shoulder.

The soldier took him into a building where other soldiers beat him for two hours before setting him free. “I returned to my house where I lived with my mother and my sister,” Alzahab told Smithsonian by email. “My mother saw me and got shocked and said, ‘You will not stay here anymore. Go away and stay alive.’” And so began his long journey into exile.

A Hope More Powerful Than the Sea: One Refugee's Incredible Story of Love, Loss, and Survival

The stunning story of a young woman, an international crisis, and the triumph of the human spirit.

Since fleeing Syria, he has covered almost 5,000 miles, traveling first through Lebanon and then Turkey, where he joined his eldest brother and worked (illegally) for a year and a half. In search of a better life, he boarded a smuggler’s boat with 52 other refugees, headed for Greece. “In the middle of the sea the engine stopped,” Alzahab says. The boat began taking on water, and “everyone started to scream.”

The Greek coast guard came to the rescue, taking the passengers to the Moria refugee camp on the island of Lesbos. Alzahab stayed there just a few days before pushing on to Athens and then Ireland, where he’s now staying at a reorientation camp in County Roscommon.

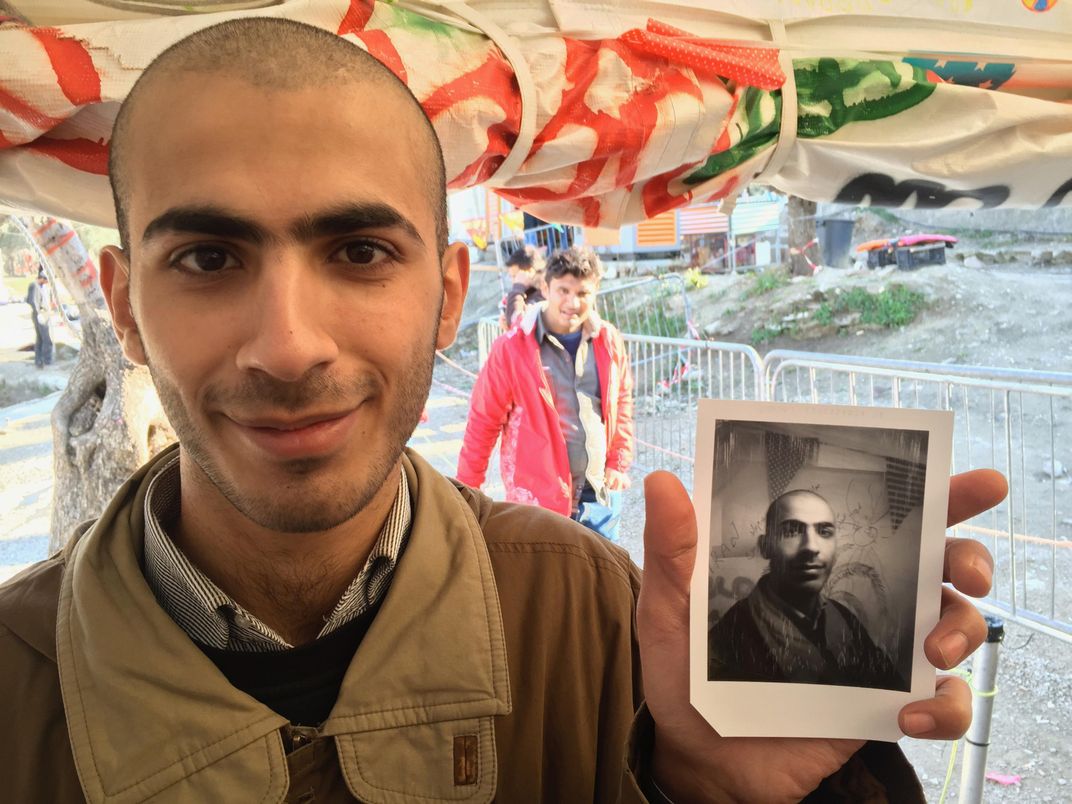

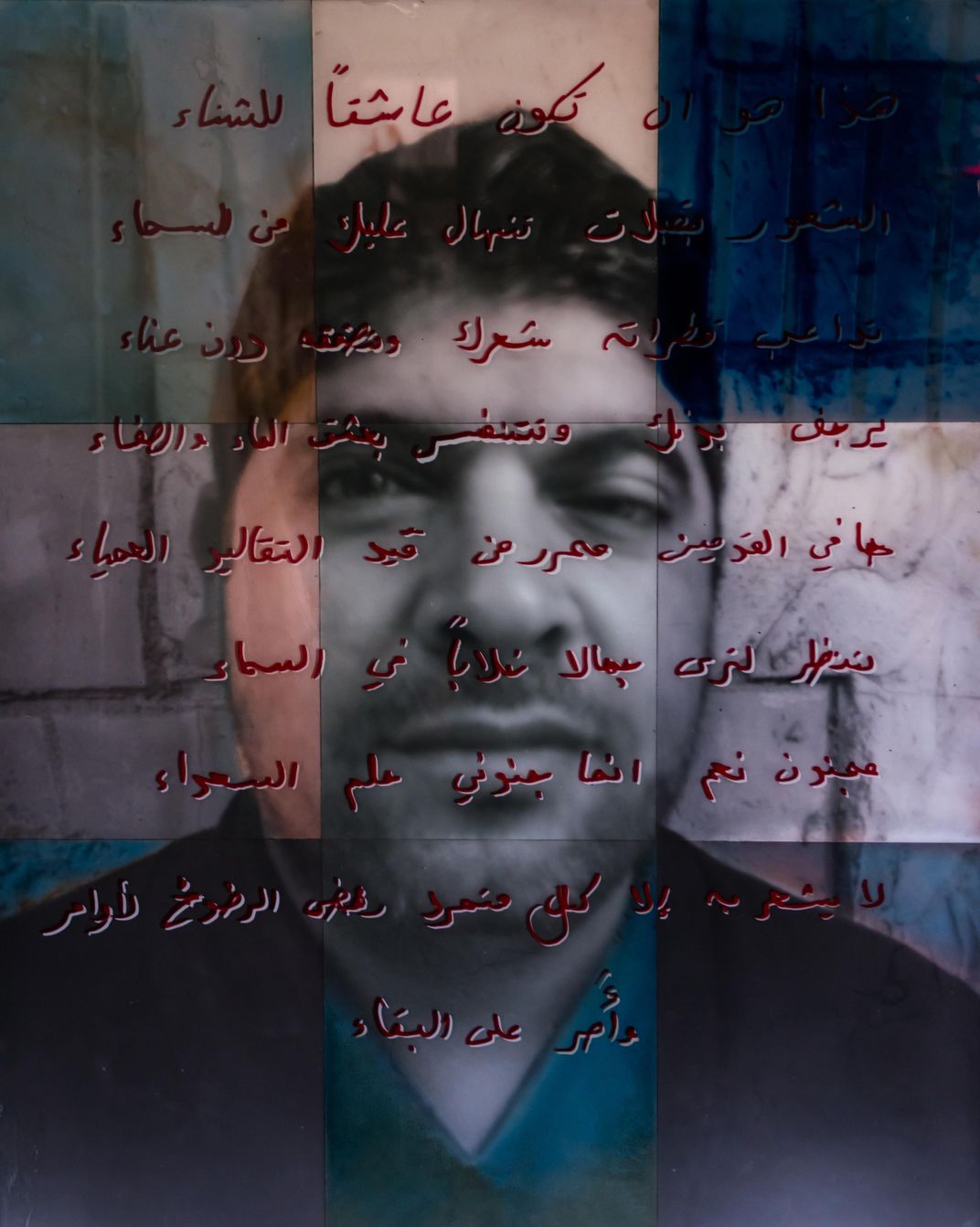

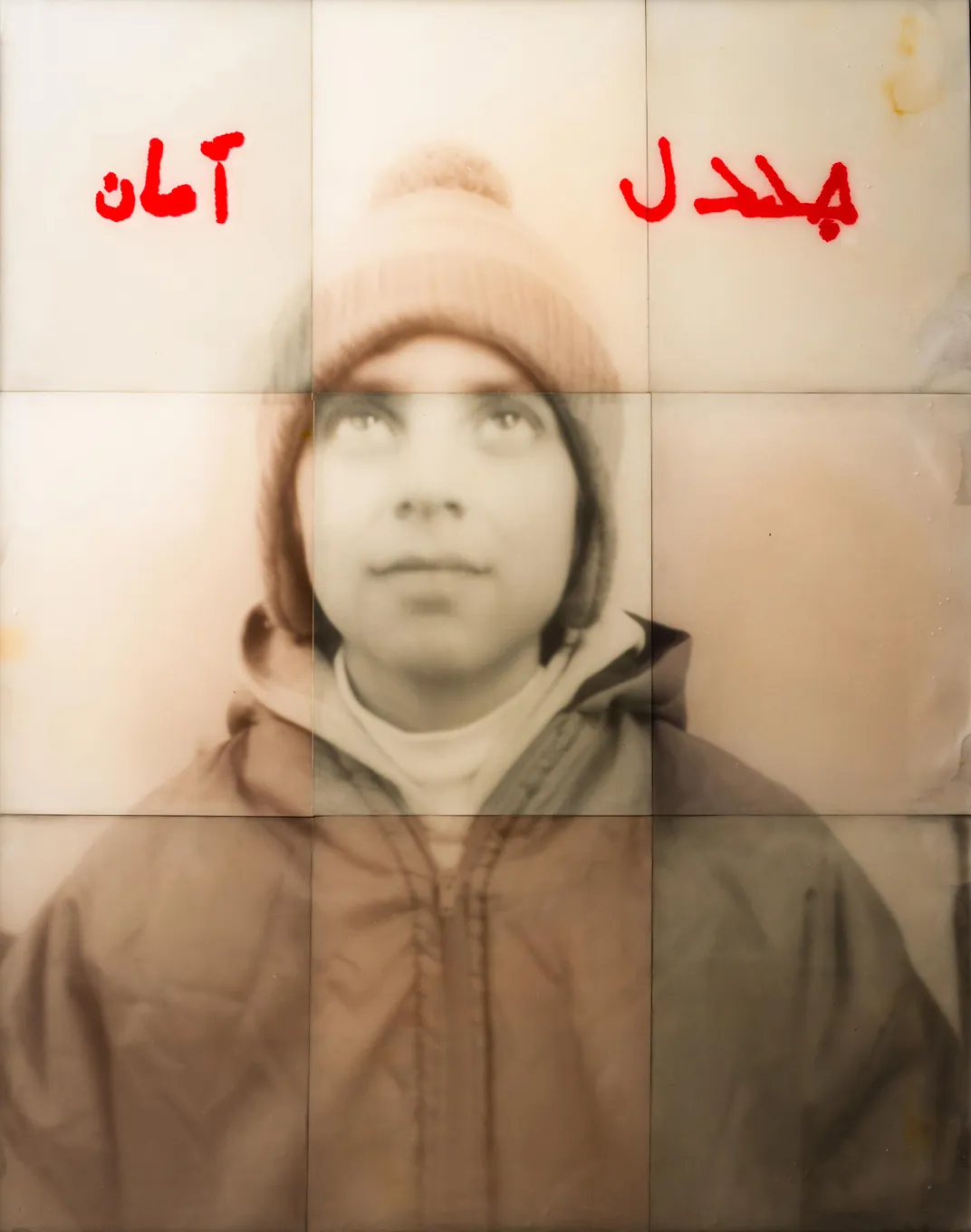

The photograph of Alzahab on these pages was taken while he was on Lesbos, where the refugee camp, a fenced-in jumble of cheek-by-jowl shelters, left a big impression. After a sleepless night—“I was afraid something would happen to me or someone would come and steal my money”—he walked to the food tent. “I was in the line, waiting, when Wayne came with his camera. I asked myself, who is this man and what is he doing here?”

Wayne is Wayne Martin Belger, an American photographer, and he was volunteering at Moria while working on a project he has titled “Us & Them,” a series of unusual portraits of people who have been oppressed, abused or otherwise pushed to the margins. The camera that caught Alzahab’s eye is indeed a curiosity: 30 pounds of copper, titanium, steel, gold and other metals welded together into a box that makes pictures by admitting only a pinhole of light. His technique requires an extended exposure on 4-by-5-inch film, but Belger sees the extra time as a chance for deeper connection with his subjects. A machinist, he built the camera himself to serve as a conversation starter. In Alzahab’s case, it worked: “I couldn’t wait to find answers to my questions, so I took my soup and went to Wayne and introduced myself to him. I asked him, ‘Can I get a picture in his camera?’ and he says, ‘Of course.’”

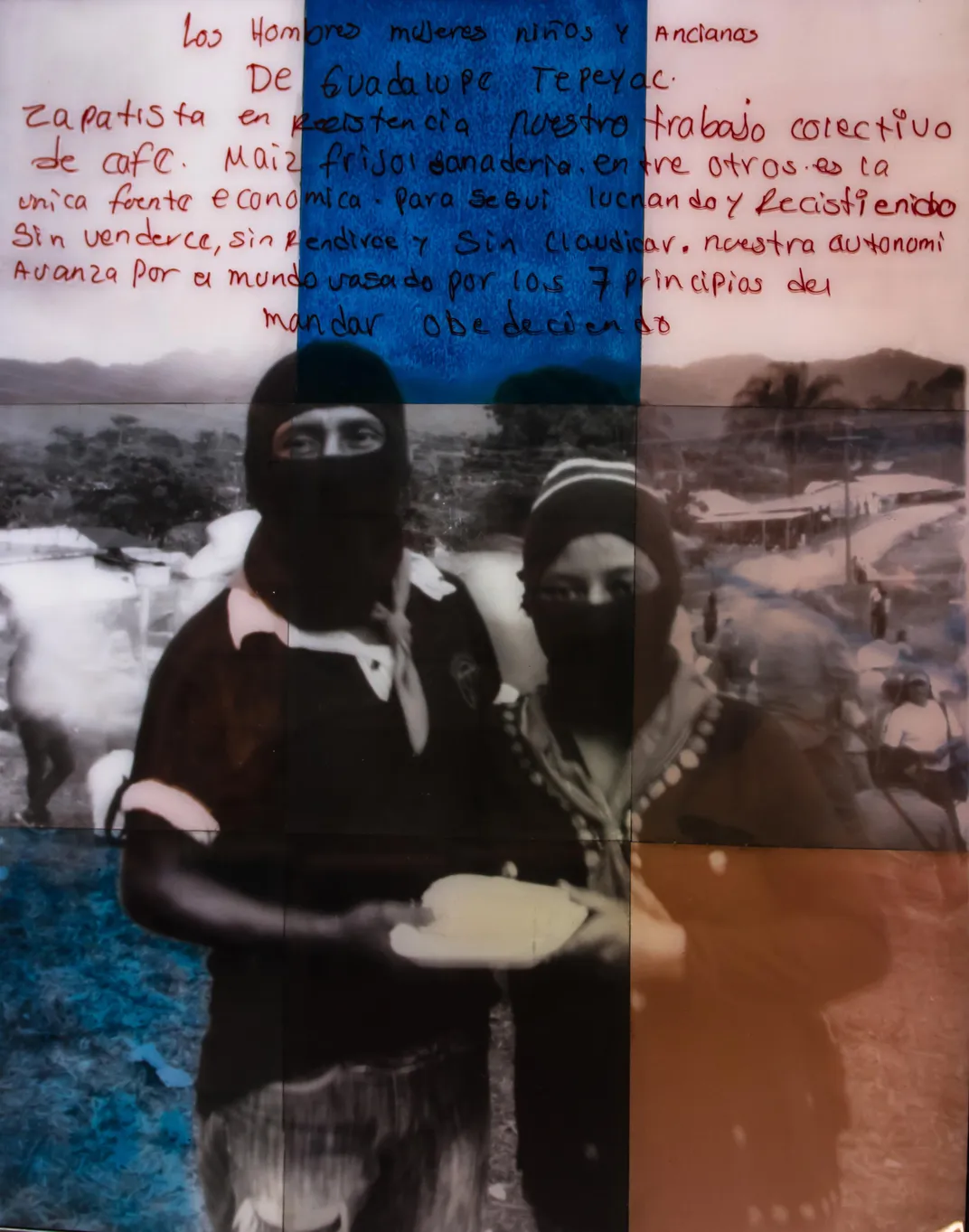

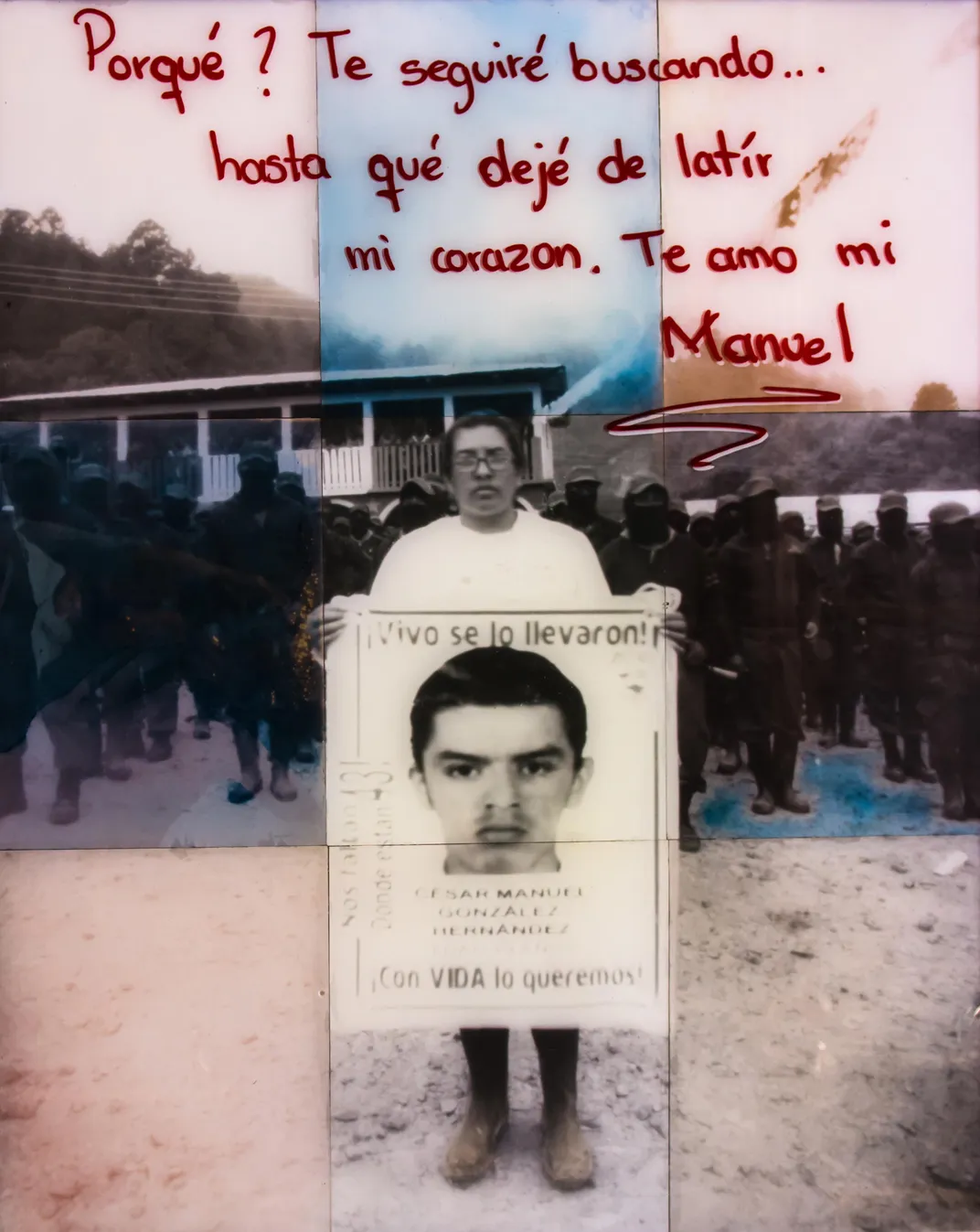

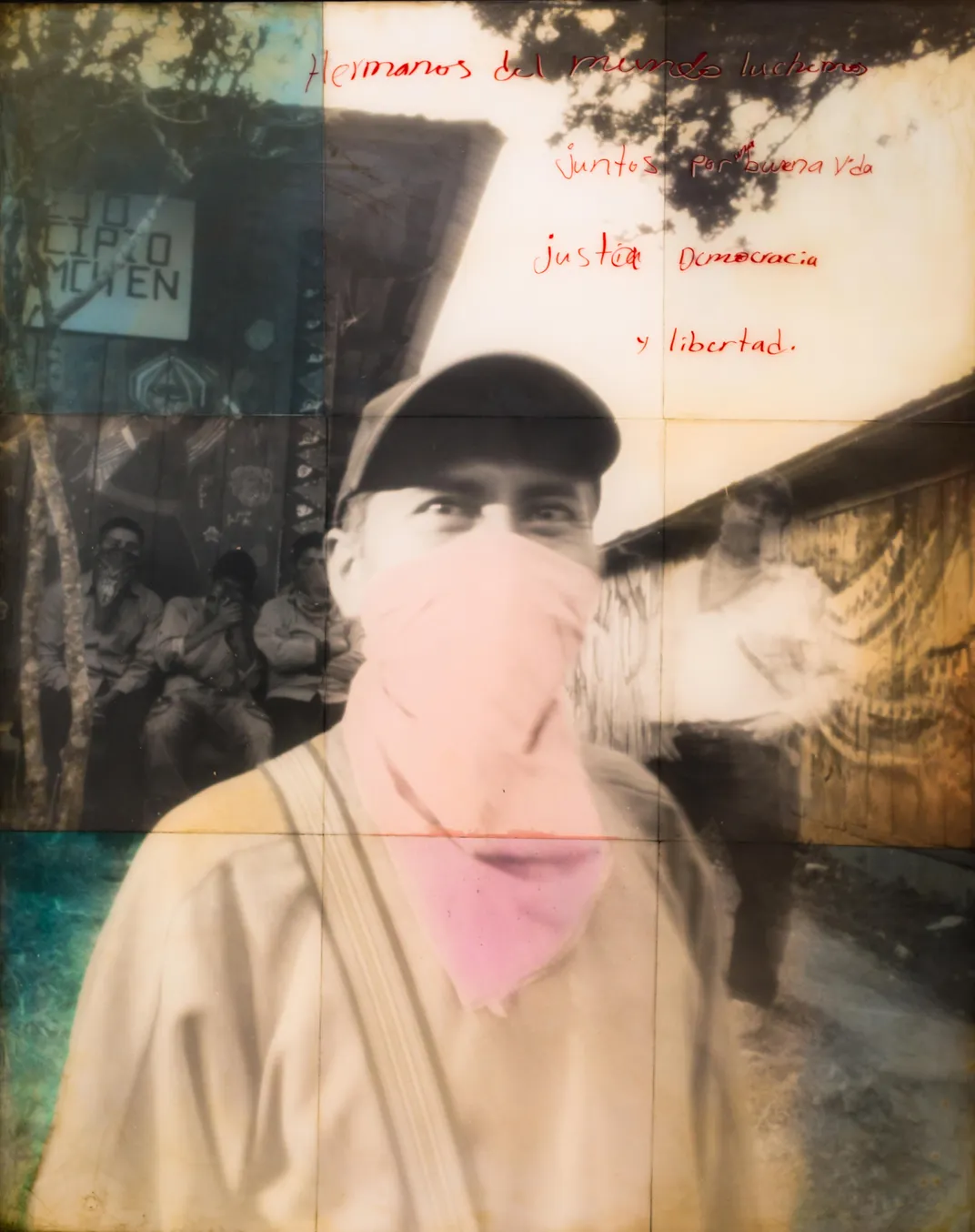

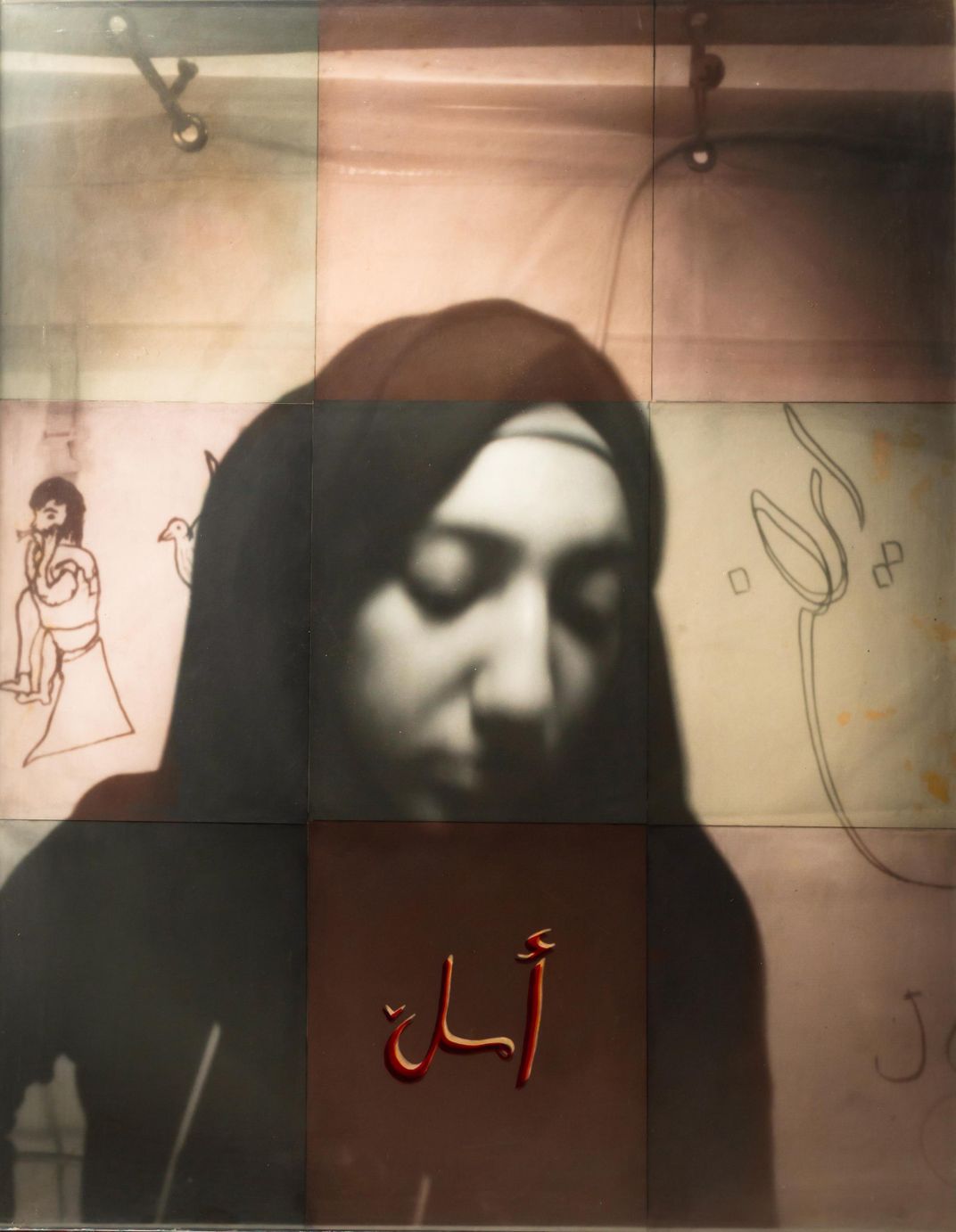

Alzahab is one of more than 100 subjects Belger has photographed in five countries so far. He went to Mexico’s southernmost state, Chiapas, to photograph the Zapatista rebels who have been fighting since 1994 for the redistribution of land and other resources, as well as autonomy for the nation’s indigenous people. In the Middle East, Belger photographed Palestinians seeking a homeland. In the United States, he spent more than two months in 2016 documenting protesters trying to halt construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline because of fears that it would foul Lakota drinking water and burial grounds.

Despite their many differences, Belger says all of his portrait subjects have been cast into a “fictitious” role as outsiders or others—“them” in his formulation—by governments, media and other powers (“us”). These divisions, which he says are rooted in “fear and ignorance,” blur faces in the crowd into faceless masses. Much of the news coverage of the international refugee crisis, he says, “is about how we don’t know who these people are, that they’re terrorists, that they’re going to come into this country and destroy everything. Then you meet somebody like Rakan and you just want to connect with him and show that there are these amazing, gentle people out there.”

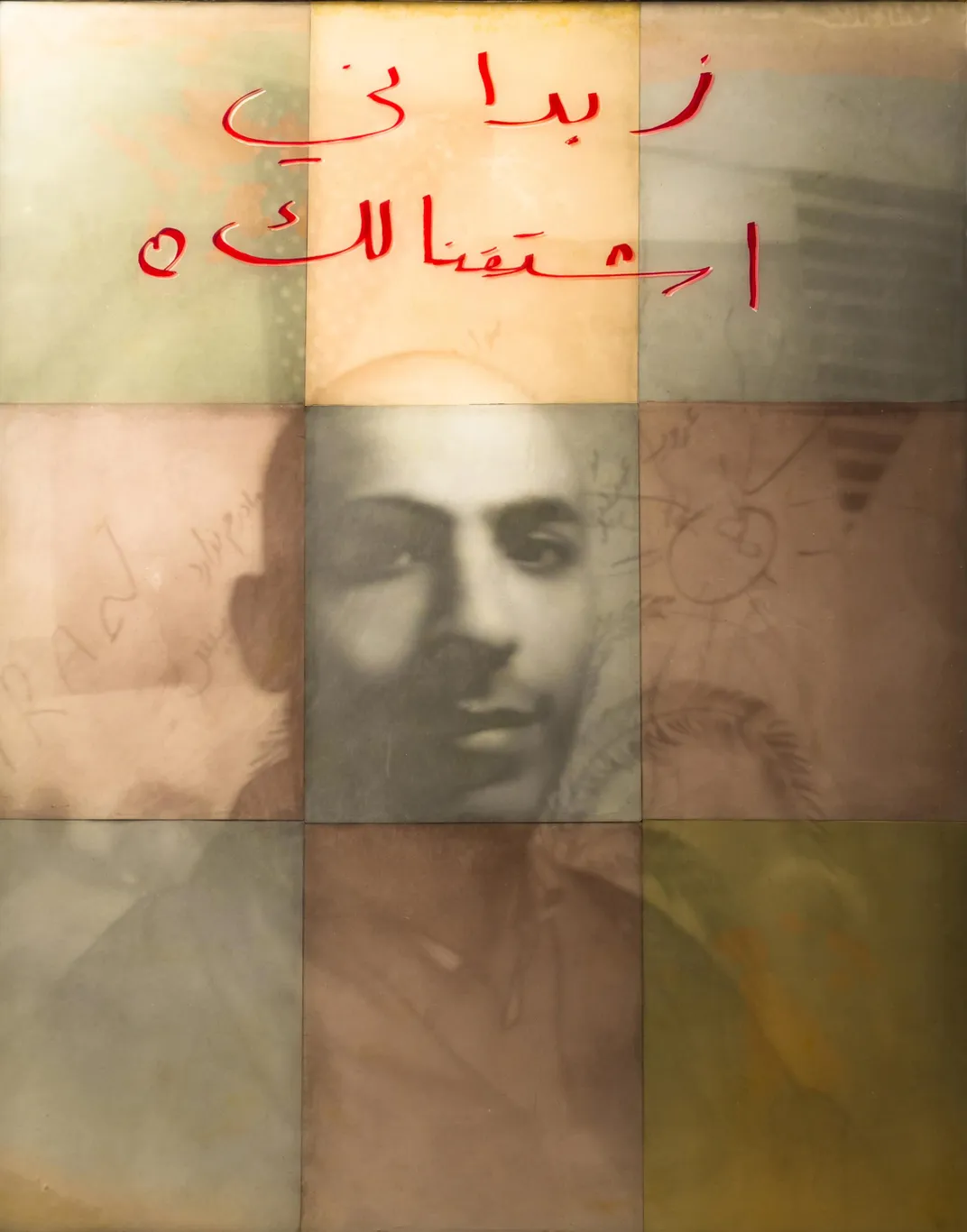

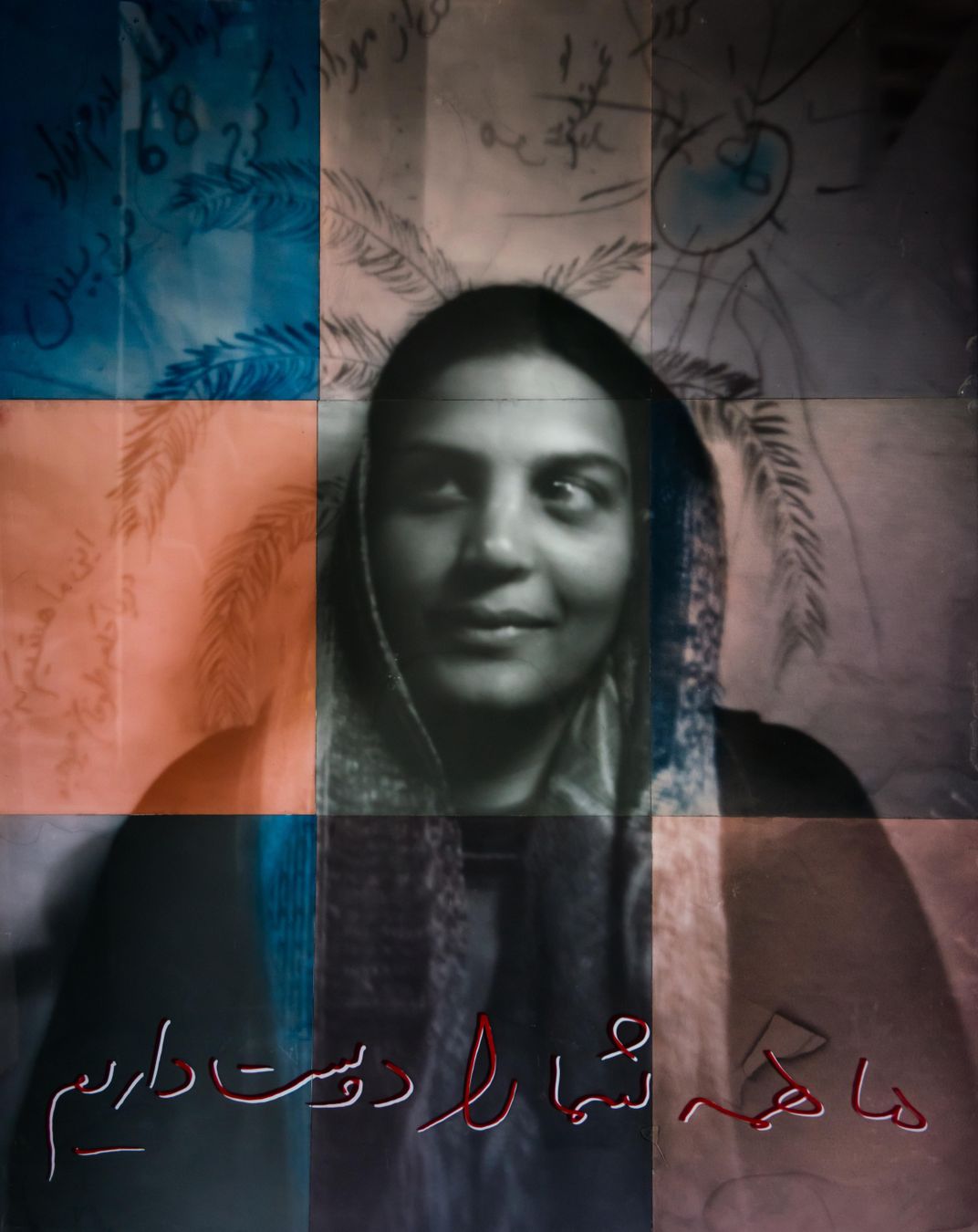

Belger emphasizes his subjects’ individuality to spotlight their humanity. After getting to know them a bit and asking them to pose for a portrait, he asks them to write “words from the heart” in their native language. After enlarging the original 4-by-5 exposures into prints measuring 48 by 60 inches, he transfers the text onto the prints, which he titles as artworks. It’s his way of collaborating with his subjects—and giving them the chance to be heard as well as seen.

Alzahab wrote, “Zabadani, we miss you,” in Arabic. He was referring to the hometown he left in 2014, a place he does not expect he’ll ever be able to revisit.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misidentified the language of the inscription for the image Moria #3. It is written in Dari, not Pashto.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1987x2305:1988x2306)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/ba/f2ba9e6c-207c-44a1-a19f-f06b6af24493/4.jpg)