Q & A with Nick Stanhope, Creator of Historypin

By merging old photographs with new mapping technology, this site fuses new connections between the generations

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Historypin-Wisconsin-State-Capitol-631.jpg)

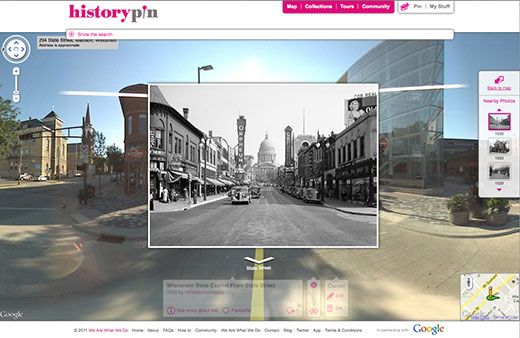

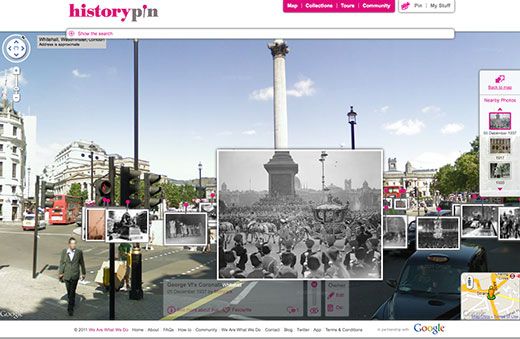

Since 2009, Nick Stanhope has been the CEO of We Are What We Do, a Britain-based nonprofit that creates products and digital tools that aim to affect people’s behaviors for the better. Historypin, one of the Oxford University graduate’s latest projects, is a website and smartphone app that allows users to “pin” old photographs and video or audio clips to Google Maps at the very locations they were snapped and recorded. The photographs can be searched by place and time, organized into collections or tours and even overlaid onto Google Street View for dramatic now-and-then comparisons.

For instance, one can see King George VI’s stagecoach passing through Trafalgar Square on his coronation day, May 12, 1937, transposed over the modern-day intersection. And, with a slide of a switch, a photograph of the ruins of the Marriott World Trade Center hotel, taken on September 11, 2001, fades to reveal the spot as it looks today.

“Historypin is a new way to see history,” says Stanhope. I spoke with him about his budding site just weeks after its mid-July launch.

How did the idea for Historypin first come about?

The roots of Historypin are in the intergenerational divide between older and young people. We focused on some of the things that we might be able to contribute in order to increase conversations, relationships and understanding and reduce negative perceptions across different generations. The most compelling part of that work was looking at the role of shared history and what a picture or a story could do to start conversations.

How do you see it being a useful tool?

Our organization as a whole spends a lot of time thinking and talking about this concept of social capital—the associations, networks and trust that define strong communities. What Robert Putnam has done, and other sociologists like him, is trace the disintegration of this social capital. I think it is a huge trend, and not something that Historypin can solve by any stretch of the imagination. But we think that by boosting the interest in local heritage and by making it exciting and relevant to people, by starting conversations—across garden fences, families, different generations and cultural groups—about heritage, we can play a role.

We talk a lot about there being a difference between “bonding” social capital and “bridging” social capital—bonding being between similar social, economic or cultural groups and bridging being across different groups. Something like Facebook is great for the social capital between people that know each other and have a connection, but it doesn’t make links beyond that. We have a very long way to go, but the aim of Historypin is to start conversations about something that is shared between people who didn’t necessarily think that they had something in common.

What has been the biggest surprise in how users have taken to it?

We’ve really loved the fact that it’s created a very diverse set of addicts. We have that core audience of institutions, history associations, local history geeks and societies, but it is also reaching into other environments and audiences in really compelling ways. We’ve had e-mails from people who run elderly care homes saying that we’ve created these fanatics who are spending time on Historypin talking about what they found, adding things, figuring stuff out. We have really liked that a younger audience is using the app to capture modern history. Our relationship with the past is stronger when we see it as a continuing process of which we are a very important part. The street corner that we walk past every day is a street corner that millions of other people have walked past for a very long time. I am fascinated by what happens when there are thousands and thousands of pieces of content related to a particular block or street corner. It allows you to see the passing of time in one very specific location. People are capturing exactly that kind of history and adding that to the archive.

How have specific communities used it?

To give an example of something that has given birth to itself completely on its own, without any involvement through us—a community of users in Nova Scotia has started up and been particularly active. A few people there have gotten everyone involved. Local archives and institutions are taking part, and there are school activities going on. Suddenly, there is this really buzzy, exciting little community of users who are coming together to talk about their shared history and their relationship with Nova Scotia history.

There was one particularly inspiring event recently at a school in a bit of Essex called Billericay. They invited older people from within the community ,and students interviewed them about their photographs, filmed and recorded their stories and made comparisons between what the area looked like then and now. It became obvious to us how these small, lovely examples can become replicated over and over again.

As of right now, over 50,000 photos and stories have been pinned. Who have been the biggest contributors?

At the moment, it is probably a fifty-fifty split between individual users and institutions in terms of the contributed content. We have well over 100 archive partners now, and I think about 60 or 70 percent are in the U.S. We have strong relationships with the Museum of the City of New York and the New York Public Library. We just did a great little pilot with the Brooklyn Museum around a pinning game, which invited users to locate some pictures that the museum didn’t know the location of. It is something we are going to look to scale up over the next few months. And, we have a very exciting, budding relationship with the Smithsonian.

Why do you think it has really caught on in the United States?

I studied U.S. history and have always loved all things American. But I oddly had never been to the States before this year. What struck me was that it just feels like Americans have a slightly more intimate relationship with local heritage. There is this thing that you notice a lot as a foreigner. When people meet for the first time in the States, the first question is always, where are you from? Where did you grow up? That always makes me want to say, “I grew up playing ball with someone’s cousin outside Chicago,” or something like that. The similar question here is probably, what do you do, or something like that, which is less welcoming or warm.

I think family, roots, neighborhoods and heritage are a very strong part of the American psyche. I just feel that there is a particular resonance in the States. People are excited about reaching into their attics and digging out their old photographs.

What other sites, focused on historical content, do you think are clever?

We are big fans of dearphotograph.com, which is based on some similar starting points that a photograph can open up a doorway to a story. There is a site called oldweather.org. It looks at the history of weather and therefore the future of climate—so, again, this idea of geospatial mapping of historical content and crowd sourcing to effective social ends.

We have always been hugely inspired by Wikipedia. There is a part of Historypin that is very similar to Wikipedia, which is the idea of this content getting better and better and more and more accurate. I guess there is a line somewhere between Flickr and Wikipedia that Historypin is trying to learn from. You can encourage people to share and put content onto a platform, and then you can encourage other people to add to, contextualize and improve the metadata and information attached to that content. We try to learn from people who have been doing it well for a long time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)