The “Quaker Comet” Was the Greatest Abolitionist You’ve Never Heard Of

Overlooked by historians, Benjamin Lay was one of the nation’s first radicals to argue for an end to slavery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/a9/21a9ef8e-cc5e-4e50-9a1b-8cf856ac6258/sep2017_f04_benjaminlay-wr.jpg)

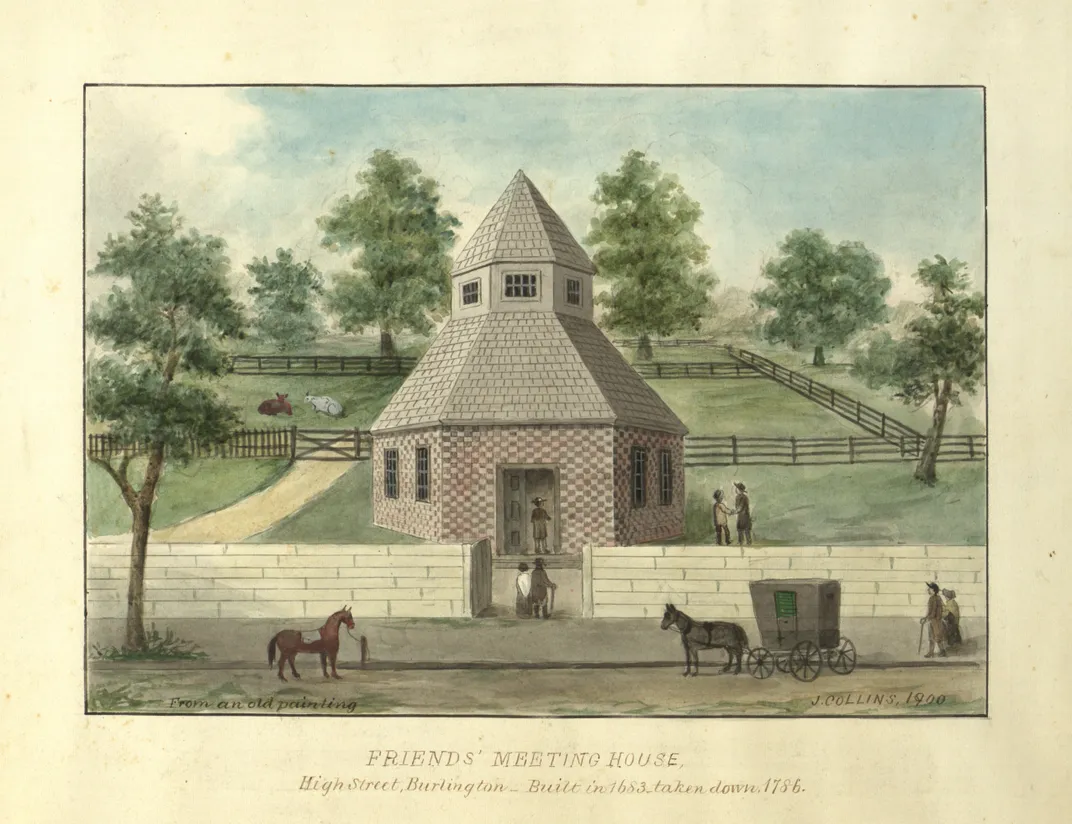

On September 19, 1738, a man named Benjamin Lay strode into a Quaker meetinghouse in Burlington, New Jersey, for the biggest event of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. He wore a great coat, which hid a military uniform and a sword. Beneath his coat Lay carried a hollowed-out book with a secret compartment, into which he had tucked a tied-off animal bladder filled with bright red pokeberry juice. Because Quakers had no formal minister or church ceremony, people spoke as the spirit moved them. Lay, a Quaker himself, waited his turn.

He finally rose to address this gathering of “weighty Quakers.” Many Friends in Pennsylvania and New Jersey had grown rich on Atlantic commerce, and many bought human property. To them Lay announced in a booming voice that God Almighty respects all peoples equally, rich and poor, men and women, white and black alike. He said that slave keeping was the greatest sin in the world and asked, How can a people who profess the golden rule keep slaves? He then threw off his great coat, revealing the military garb, the book and the blade.

A murmur filled the hall as the prophet thundered his judgment: “Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who enslave their fellow creatures.” He pulled out the sword, raised the book above his head, and plunged the sword through it. People gasped as the red liquid gushed down his arm; women swooned. To the shock of all, he spattered “blood” on the slave keepers. He prophesied a dark, violent future: Quakers who failed to heed the prophet’s call must expect physical, moral and spiritual death.

The room exploded into chaos, but Lay stood quiet and still, “like a statue,” a witness remarked. Several Quakers quickly surrounded the armed soldier of God and carried him from the building. He did not resist. He had made his point.

**********

This spectacular performance was one moment of guerrilla theater among many in Lay’s life. For nearly a quarter-century he railed against slavery in one Quaker meeting after another in and around Philadelphia, confronting slave owners and slave traders with a savage, most un-Quaker fury. He insisted on the utter depravity and sinfulness of “Man-stealers,” who were, in his view, the literal spawn of Satan. He considered it his Godly duty to expose and drive them out. At a time when slavery seemed to many people around the world as natural and unchangeable as the sun, the moon and the stars, he became one of the very first to call for the abolition of slavery and an avatar of confrontational public protest.

He was notable for his physique. Benjamin Lay was a dwarf, or “little person,” standing just over four feet tall. He was called a hunchback because of an extreme curvature of his spine, a medical condition called kyphosis. According to a fellow Quaker, “His head was large in proportion to his body; the features of his face were remarkable, and boldly delineated, and his countenance was grave and benignant. ...His legs were so slender, as to appear almost unequal to the purpose of supporting him, diminutive as his frame.” Yet I have found no evidence that Lay thought himself in any way diminished, or that his body kept him from doing anything he wanted to do. He called himself “little Benjamin,” but he also likened himself to “little David” who slew Goliath. He did not lack confidence in himself or his ideas.

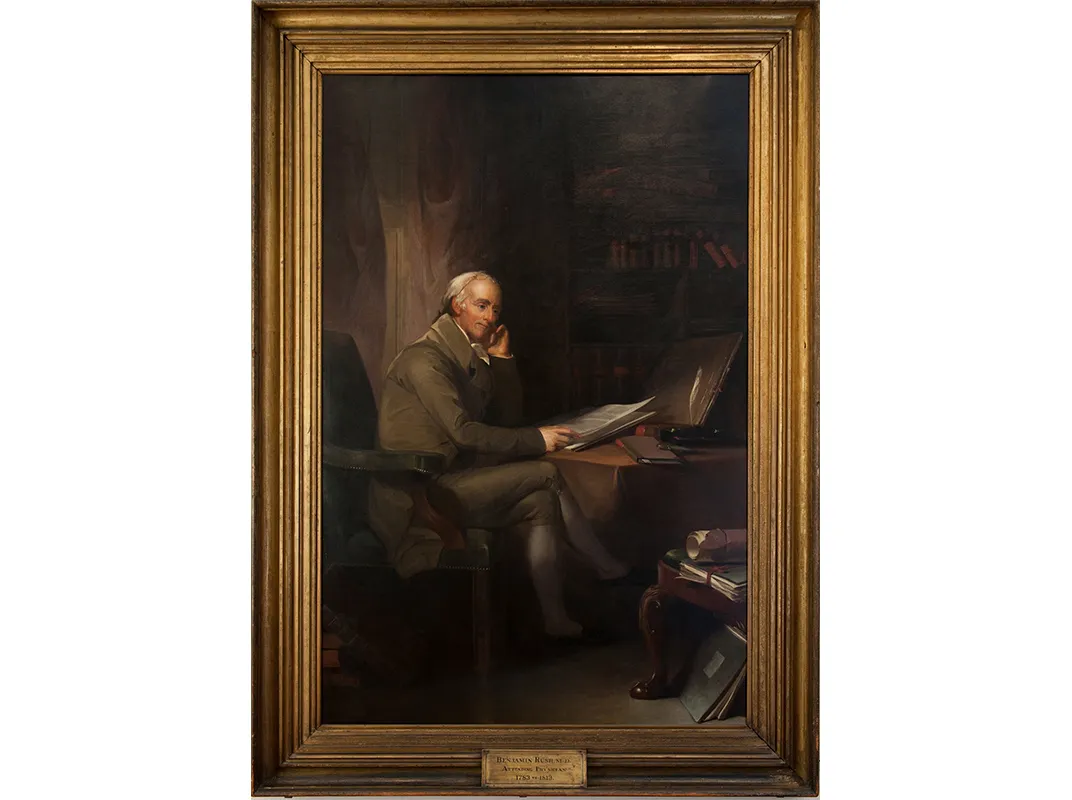

His confrontational methods made people talk: about him, his ideas, the nature of Quakerism and Christianity, and, most of all, slavery. His first biographer, Benjamin Rush—physician, reformer, abolitionist and signer of the Declaration of Independence—noted that “there was a time when the name of this celebrated Christian Philosopher...was familiar to every man, woman, and to nearly every child, in Pennsylvania.” For or against, everyone told stories about Benjamin Lay.

And yet he appears only occasionally in histories of abolition, usually as a minor, colorful figure of suspect sanity. By the 19th century he was regarded as “diseased” in his intellect and later as “cracked in the head.” To a large extent this image has persisted in modern histories. David Brion Davis, a leading historian of abolitionism, dismissed him as a mentally deranged, obsessive “little hunchback.” Lay gets better treatment from amateur Quaker historians, who include him in their pantheon of antislavery saints, and by many professional historians of Quakerism. But he remains little known among historians, and almost totally unknown to the general public.

**********

Benjamin Lay was born in 1682 in Essex, a part of England then known for textile production, protest and religious radicalism. He was a third-generation Quaker and would become more fervently dedicated to the faith than his parents or grandparents. In the late 1690s, a teenage Benjamin left his parents’ cottage to work as a shepherd on the farm of a half-brother in eastern Cambridgeshire. When the time came for him to begin life on his own, his father apprenticed him to a master glover in the Essex village of Colchester. Benjamin had loved being a shepherd, but he did not like being a glover, which is probably the main reason he ran away to London to become a sailor in 1703 at age 21.

The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist

With passion and historical rigor, Rediker situates Lay as a man who fervently embodied the ideals of democracy and equality as he practiced a unique concoction of radicalism nearly three hundred years ago.

For the next dozen years Lay lived alternately in London and at sea, where, for months at a time, he shared cramped quarters with multiethnic fellow workers, cooperating within a strict hierarchy beneath a captain with extreme powers of discipline, to move ships and their cargoes around the world. The experience—which included hearing sailors’ stories of the slave trade—gave him a hard-earned, hard-edged cosmopolitanism. Later, during an 18-month sojourn as a shopkeeper in Barbados, he saw an enslaved man kill himself rather than submit to yet another whipping; that and myriad other barbarities in that British colony both traumatized him and drove his passion for antislavery.

Though his formal education was limited, he studied the history of Quakerism and drew inspiration from its origins in the English Revolution, when a motley crew of uppity commoners used the quarrel between Cavalier (Royalist) and Roundhead (Parliamentarian) elites to propose their own solutions to the problems of the day. Many of these radicals were denounced as “antinomians”—people who believed that no one had the right or power to control the human conscience. Lay never used the word—it was largely an epithet—but he was deeply antinomian. This was the wellspring of his radicalism.

The earliest record of Lay’s active participation in organized Quakerism originated in America, in 1717. Even though he was based in London at the time, he had sailed to Boston to request a certificate of approval from local Quakers to marry Sarah Smith of Deptford, England. She was, like him, a little person, but, unlike him, a popular and admired preacher in her Quaker community. When the Massachusetts Quakers, in an act of due diligence, asked Lay’s home congregation in London to certify that he was a Friend in good standing, the reply noted that he was “clear from Debts and from women in relation to marriage,” but added: “We believe he is Convinced of the Truth but for want of keeping low and humble in his mind, hath by an Indiscreet Zeal been too forward to appear in our publick Meetings.” Lay was disturbing the Quaker meetings’ peace by calling out those he believed were “covetous”—corrupted by worldly wealth.

Thus the “Quaker Comet,” as he was later called, blazed into the historical record. He received approval to marry Sarah Smith, but a lifelong pattern of troublemaking followed. He was disowned, or formally expelled, from two congregations in England. Further strife lay ahead when the couple boarded a ship bound for Philadelphia in mid-March 1732. It was not easy to be so far ahead of one’s time.

**********

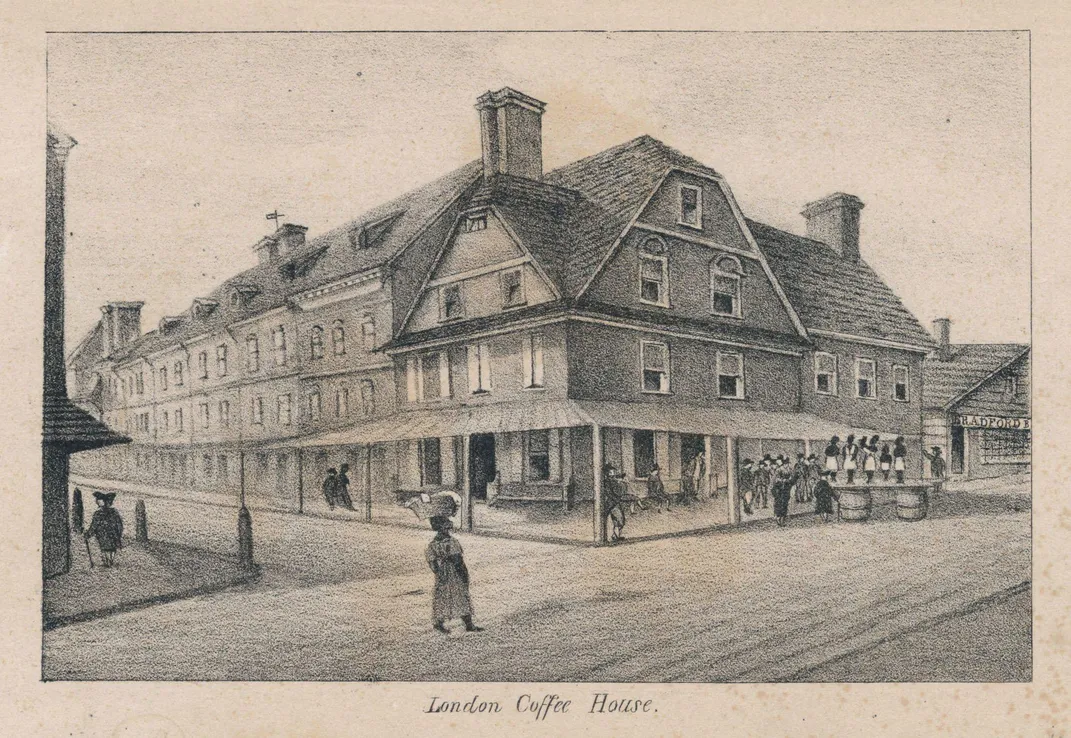

Benjamin and Sarah looked forward to joining William Penn’s “Holy Experiment.” Like the many thousands of others who had sailed to “this good land,” as he called Pennsylvania, they anticipated a future of “great Liberty.” Philadelphia was North America’s largest city, and it included the world’s second-largest Quaker community.

Its center was the Great Meeting House, at Market and Second streets, home of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting. Among those popularly known as “men of renown” were Anthony Morris Jr., Robert Jordan Jr., Israel Pemberton Sr. and John Kinsey Jr. They led both the religious and political life of the colony, even to the point of vetting, through the Quaker Board of Overseers, all publications. In fact, they epitomized one side of the early history of Quakerism, in which Friends came to Pennsylvania to “do good” and in turn “did well”—very well indeed, to judge by the wealth and power they amassed. Three of those leaders, and probably all four, owned slaves. So did the majority of Philadelphia Quakers.

Having lived the previous ten years in England, where the sights of slavery were few, Lay was shocked when he arrived in Philadelphia. To be sure, bondage in his new home was fundamentally different from what he had witnessed in Barbados more than a decade earlier; only one in ten persons was enslaved in the city, compared with almost nine in ten on the island. The levels of violence and repression were significantly lower. But bondage, violence and repression were a daily reality in the City of Brotherly Love.

Enslaved men, Lay noted, would “Plow, sow, thresh, winnow, split Rails, cut Wood, clear Land, make Ditches and Fences, fodder Cattle, run and fetch up the Horses.” He saw enslaved women busy with “all the Drudgery in Dairy and Kitchen, within doors and without.” These grinding labors he contrasted with the idleness of the slave owners—the growling, empty bellies of the enslaved and the “lazy Ungodly bellies” of their masters. Worse, he explained with rising anger, slave keepers would perpetuate this inequality by leaving these workers as property to “proud, Dainty, Lazy, Scornful, Tyrannical and often beggarly Children for them to Domineer.”

Soon after arriving in Philadelphia, Lay befriended Ralph Sandiford, who had published an indictment of slavery over the objection of the Board of Overseers three years earlier. Lay found a man in poor health, suffering “many Bodily Infirmities” and, more disturbingly, “sore Affliction of mind,” which Lay attributed to persecution by Quaker leaders. Sandiford had recently moved from Philadelphia to a log cabin about nine miles northeast, partly to escape his enemies. Lay visited this “very tender hearted Man” regularly over the course of almost a year, the final time as Sandiford lay on his deathbed in “a sort of Delirium,” and noted that he died “in great Perplexity of mind” in May 1733, at 40 years of age. Lay concluded “oppression...makes a wise man Mad.” Yet he took up Sandiford’s struggle.

Lay began to stage public protests to shock the Friends of Philadelphia into awareness of their own moral failings about slavery. Conscious of the hard, exploited labor that went into making commodities such as tobacco and sugar, he showed up at a Quaker yearly meeting with “three large tobacco pipes stuck in his bosom.” He sat between the galleries of men and women elders and ministers. As the meeting came to an end, he rose in indignant silence and “dashed one pipe among the men ministers, one among the women ministers, and the third among the congregation assembled.” With each smashing blow he protested slave labor, luxury and the poor health caused by smoking the stinking sotweed. He sought to awaken his brothers and sisters to the politics of the seemingly most insignificant choices.

When winter rolled in, Lay used a deep snowfall to make a point. One Sunday morning he stood at a gateway to the Quaker meetinghouse, knowing all Friends would pass his way. He left “his right leg and foot entirely uncovered” and thrust them into the snow. Like the ancient philosopher Diogenes, who also trod barefoot in snow, he again sought to shock his contemporaries into awareness. One Quaker after another took notice and urged him not to expose himself to the freezing cold lest he get sick. He replied, “Ah, you pretend compassion for me but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad.”

He also began to disrupt Quaker meetings. “Benjamin gave no peace” to slave owners, the 19th-century radical Quaker Isaac Hopper recalled hearing as a child. “As sure as any character attempted to speak to the business of the meeting, he would start to his feet and cry out, ‘There’s another negro-master!’”

It came as no surprise, to Lay or anyone else, that ministers and elders had him removed from one gathering after another. Indeed they appointed a “constabulary” to keep him out of meetings all around Philadelphia, and even that wasn’t enough. After he was tossed into the street one rainy day, he returned to the main door of the meetinghouse and lay down in the mud, requiring every person leaving the meeting to step over his body.

**********

Perhaps because of rising conflict with the “men of renown,” Benjamin and Sarah left Philadelphia by the end of March 1734, moving eight miles north to Abington. The move required a certificate from the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting stating that they were members in good standing, to present to the local Quaker meeting in their new home. It was Lay’s bad luck that letters from enemies in England found their way to Robert Jordan Jr., which gave Jordan a pretext to mount a protracted challenge to Lay’s membership in Philadelphia.

During that challenge, the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting went out of its way to note that Sarah was a member in good standing—“she appearing to be of a good Conversation during her residence here”—while Benjamin was not. This judgment would be a source of lifelong bitterness for Lay, especially after Sarah died, of unknown causes, in late 1735, after 17 years of marriage. He later would accuse Jordan of having been an instrument in “the Death of my Dear Wife.” It may have been her death that prompted him to take his activism into print—an act that set in motion his biggest confrontation yet.

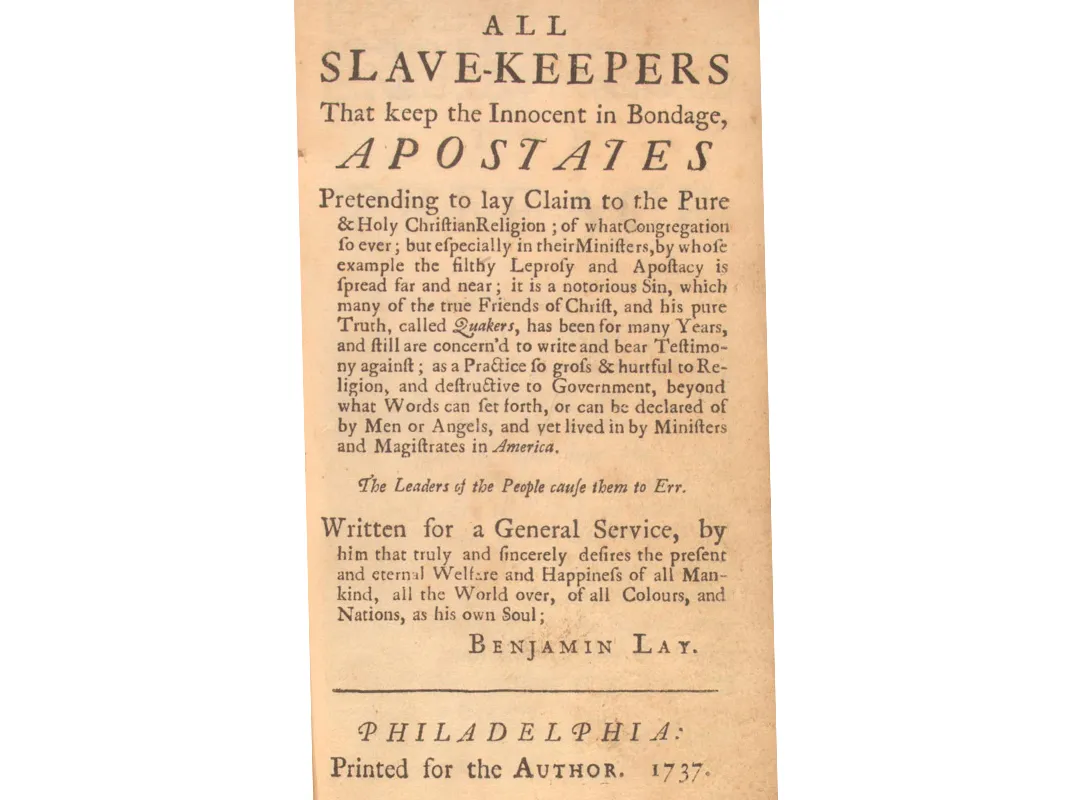

For two years Lay spent much of his time writing a strange, passionate treatise, All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. The book makes for odd reading—a mixture of autobiography, prophetic biblical polemic against slavery, writings by others, surreal descriptions of slavery in Barbados and a scathing account of his struggles against slave owners within the Quaker community. Lay knew the Board of Overseers would never approve his book, so he went directly to his friend, the printer Benjamin Franklin, and asked him to publish it, which he did in August 1738. It became a founding text of Atlantic antislavery, and an important advance in abolitionist thought. No one had ever taken such a militant, uncompromising, universal stand against slavery.

Lay’s originality lay in his utterly uncompromising attitude. Slave keeping was a “filthy,” “gross,” “heinous,” “Hellish” sin, a “soul Sin,” “the greatest Sin in the World.” He argued that “no Man or Woman, Lad or Lass ought to be suffered, to pretend to Preach Truth in our Meetings, while they live in that Practice [of slave keeping]; which is all a lie.” The hypocrisy, in his view, was unbearable. Since slave keepers bore the “Mark of the Beast”—they embodied Satan on earth—they must be cast out of the church.

The book reflected a generational struggle among Quakers over slave keeping during the 1730s, when Quaker attitudes toward the peculiar institution were beginning to change. Lay said repeatedly that his most determined enemies were “elders,” many of whom were wealthy, like Anthony Morris, Israel Pemberton and John Kinsey; others were ministers, like Jordan. At one point Lay declared that it was “Time for such old rusty Candlesticks to be moved out of their Places.” At other points, he attacked elders personally, such as when he referred to “the furious Dragon”—a diabolical beast from Revelation—giving “the nasty Beast his Power and his Seat, his Chair to sit in as Chief Judge”—an allusion to Kinsey, who was clerk of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and soon to be the attorney general of Pennsylvania and the chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

Very little of the debate on the subject was written down or published, so it is hard to know precisely how rank-and-file Friends received Lay’s book. The Overseers’ reaction, however, was recorded. That fall, the board issued an official condemnation, signed by John Kinsey, proclaiming that the book “contains gross Abuses, not only against some of their Members in particular, but against the whole Society,” and adding: “That the Author is not of their religious Community.” The meeting in Abington, too, expelled the Author.

And so Lay became, in 1738, the last of a very few Quakers disowned for protests against slavery.

**********

Disowned and denounced, Lay still attended worship services and argued about the evils of slavery. But he also began to build a new revolutionary way of life, a broader, more radical vision of human possibility.

He built his own home, selecting a spot in Abington “near a fine spring of water” and erecting a small cottage in a “natural excavation in the earth”—a cave. He lined the entrance with stone and created a roof with sprigs of evergreen. The cave was apparently quite spacious, with room for a spinning jenny and a large library. Nearby he planted apple, peach and walnut trees and tended a bee colony a hundred feet long. He cultivated potatoes, squash, radishes and melons.

Lay lived simply, in “plain” style, as was the Quaker way, but he went further: He ate only fruits and vegetables, drank only milk and water; he was very nearly a vegan two centuries before the word was invented. Because of the divine pantheistic presence of God he perceived in all living things, he refused to eat “flesh.” Animals too were “God’s creatures.” He made his own clothes in order to avoid the exploitation of the labor of others, including animals.

In addition to boycotting all commodities produced by slave labor, Lay by his example and his writing challenged society to eradicate all forms of exploitation and oppression and live off the “innocent fruits of the earth.”

In 1757, when he was 75, Lay’s health began to deteriorate. His mind remained clear and his spirit as fiery as ever, but he gave up his habitual long hikes and stayed home. He tended his garden, spun flax and engaged in other “domestic occupations.”

The following year, a visitor brought news. A group of Quaker reformers had undertaken an internal “purification” campaign, calling for a return to simpler ways of living, stricter church discipline and a gradual end to slavery, all to appease an angry God. Now, Lay was told, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, after much agitation from below, had initiated a process to discipline and eventually disown Quakers who traded slaves. Slaveholding itself was still permitted—and would be for another 18 years—but the first big step toward abolition had been taken.

Lay fell silent. After “a few moments reflection,” he rose from his chair and “in an attitude of devotional reverence” said, “Thanksgiving and praise be rendered unto the Lord God.” A few moments later he added, “I can now die in peace.”

Soon he took a turn for the worse. The specific causes are unknown. His friends convened to discuss what they could do for him. He asked to be taken to the home of his friend Joshua Morris in Abington. There he died, on February 3, 1759, at the age of 77.

Like most Quakers of his time, Lay opposed carrying distinctions of class into the afterlife; he was buried in an unmarked grave, near his cherished Sarah, in the Quaker burial ground in Abington. In the book of “Burials at Abington” for the year 1759 is a simple notation: “Benjamin Lay of Abington died 2 Mo. 7th Inter’d 9th, Aged 80 Years.” (The scribe was off by three years on the age and four days on the date.) Other names in the book had in the margin an “E” for “elder,” an “M” for minister and a notation of whether the person was a member of the congregation. Lay’s name bore no such notation, which would have been a source of pain and sadness to him. He was buried as a stranger to the faith he loved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.