Quite Likely the Worst Job Ever

A British journalist provides us with a window into the lives of the men who made their living from combing for treasures in London’s sewers

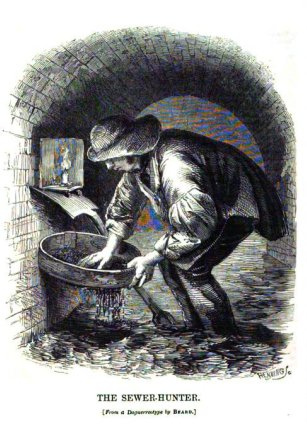

A tosher at work c. 1850 ,sieving raw sewage in one of the dank, dangerous and uncharted sewers beneath the streets of London. From Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor.

To live in any large city during the 19th century, at a time when the state provided little in the way of a safety net, was to witness poverty and want on a scale unimaginable in most Western countries today. In London, for example, the combination of low wages, appalling housing, a fast-rising population and miserable health care resulted in the sharp division of one city into two. An affluent minority of aristocrats and professionals lived comfortably in the good parts of town, cossetted by servants and conveyed about in carriages, while the great majority struggled desperately for existence in stinking slums where no gentleman or lady ever trod, and which most of the privileged had no idea even existed. It was a situation accurately and memorably skewered by Dickens, who in Oliver Twist introduced his horrified readers to Bill Sikes’s lair in the very real and noisome Jacob’s Island, and who has Mr. Podsnap, in Our Mutual Friend, insist: “I don’t want to know about it; I don’t choose to discuss it; I don’t admit it!”

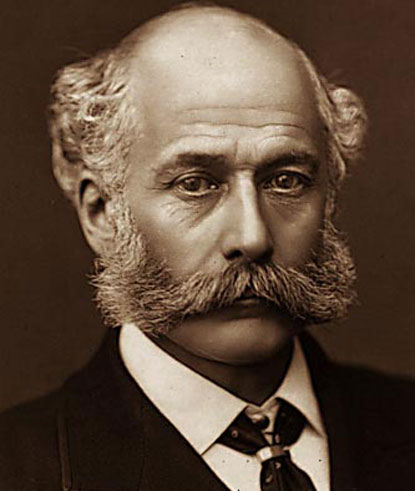

Out of sight and all too often out of mind, the working people of the British capital nonetheless managed to conjure livings for themselves in extraordinary ways. Our guide to the enduring oddity of many mid-Victorian occupations is Henry Mayhew, whose monumental four-volume study of London Labour and the London Poor remains one of the classics of working-class history. Mayhew–whom we last met a year ago, describing the lives of London peddlers of this period–was a pioneering journalist-cum-sociologist who interviewed representatives of hundreds of eye-openingly odd trades, jotting down every detail of their lives in their own words to compile a vivid, panoramic overview of everyday life in the mid-Victorian city.

Among Mayhew’s more memorable meetings were encounters with the “bone grubber,” the “Hindoo tract seller,” an eight-year-old girl watercress-seller and the “pure finder,” whose surprisingly sought-after job was picking up dog mess and selling it to tanners, who then used it to cure leather. None of his subjects, though, aroused more fascination–or greater disgust–among his readers than the men who made it their living by forcing entry into London’s sewers at low tide and wandering through them, sometimes for miles, searching out and collecting the miscellaneous scraps washed down from the streets above: bones, fragments of rope, miscellaneous bits of metal, silver cutlery and–if they were lucky–coins dropped in the streets above and swept into the gutters.

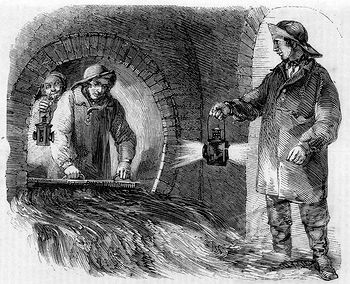

A London sewer in the19th century. This one, as evidenced by the shaft of light penetrating through a grating, must be close to the surface; others ran as deep as 40 feet beneath the city.

Mayhew called them “sewer hunters” or “toshers,” and the latter term has come to define the breed, though it actually had a rather wider application in Victorian times–the toshers sometimes worked the shoreline of the Thames rather than the sewers, and also waited at rubbish dumps when the contents of damaged houses were being burned and then sifted through the ashes for any items of value. They were mostly celebrated, nonetheless, for the living that the sewers gave them, which was enough to support a tribe of around 200 men–each of them known only by his nickname: Lanky Bill, Long Tom, One-eyed George, Short-armed Jack. The toshers earned a decent living; according to Mayhew’s informants, an average of six shillings a day–an amount equivalent to about $50 today. It was sufficient to rank them among the aristocracy of the working class–and, as the astonished writer noted, “at this rate, the property recovered from the sewers of London would have amounted to no less than £20,000 per annum.”

The toshers’ work was dangerous, however, and–after 1840, when it was made illegal to enter the sewer network without express permission, and a £5 reward was offered to anyone who informed on them–it was also secretive, done mostly at night by lantern light. “They won’t let us in to work the shores,” one sewer-hunter complained, “as there’s a little danger. They fears as how we’ll get suffocated, but they don’t care if we get starved!”

Quite how the members of the profession kept their work a secret is something of a puzzle, for Mayhew makes it clear that their dress was highly distinctive. “These toshers,” he wrote,

may be seen, especially on the Surrey side of the Thames, habited in long greasy velveteen coats, furnished with pockets of vast capacity, and their nether limbs encased in dirty canvas trousers, and any old slops of shoes… provide themselves, in addition, with a canvas apron, which they tie round them, and a dark lantern similar to a policeman’s; this they strap before them on the right breast, in such a manner that on removing the shade, the bull’s eye throws the light straight forward when they are in an erect position… but when they stoop, it throws the light directly under them so that they can distinctly see any object at their feet. They carry a bag on their back, and in their left hand a pole about seven or eight feet long, one one end of which there is a large iron hoe.

Henry Mayhew chronicled London street life in the 1840s and ’50s, producing an incomparable account of desperate living in the working classes’ own words.

This hoe was the vital tool of the sewer hunters’ trade. On the river, it sometimes saved their lives, for “should they, as often happens, even to the most experienced, sink in some quagmire, they immediately throw out the long pole armed with the hoe, and with it seizing hold of any object within reach, are thereby enabled to draw themselves out.” In the sewers, the hoe was invaluable for digging into the accumulated muck in search of the buried scraps that could be cleaned and sold.

Knowing where to find the most valuable pieces of detritus was vital, and most toshers worked in gangs of three or four, led by a veteran who was frequently somewhere between 60 and 80 years old. These men knew the secret locations of the cracks that lay submerged beneath the surface of the sewer-waters, and it was there that cash frequently lodged. “Sometimes,” Mayhew wrote, “they dive their arm down to the elbow in the mud and filth and bring up shillings, sixpences, half-crowns, and occasionally half-sovereigns and sovereigns. They always find these the coins standing edge uppermost between the bricks in the bottom, where the mortar has been worn away.”

Life beneath London’s streets might have been surprisingly lucrative for the experienced sewer-hunter, but the city authorities had a point: It was also tough, and survival required detailed knowledge of its many hazards. There were, for example, sluices that were raised at low tide, releasing a tidal wave of effluent-filled water into the lower sewers, enough to drown or dash to pieces the unwary. Conversely, toshers who wandered too far into the endless maze of passages risked being trapped by a rising tide, which poured in through outlets along the shoreline and filled the main sewers to the roof twice daily.

Yet the work was not was unhealthy, or so the sewer-hunters themselves believed. The men that Mayhew met were strong, robust and even florid in complexion, often surprisingly long-lived–thanks, perhaps, to immune systems that grew used to working flat out–and adamantly convinced that the stench that they encountered in the tunnels “contributes in a variety of ways to their general health.” They were more likely, the writer thought, to catch some disease in the slums they lived in, the largest and most overcrowded of which was off Rosemary Lane, on the poorer south side of the river.

Access is gained to this court through a dark narrow entrance, scarcely wider than a doorway, running beneath the first floor of one of the houses in the adjoining street. The court itself is about 50 yards long, and not more than three yards wide, surrounded by lofty wooden houses, with jutting abutments in many upper storeys that almost exclude the light, and give them the appearance of being about to tumble down upon the heads of the intruder. The court is densely inhabited…. My informant, when the noise had ceased, explained the matter as follows: “You see, sir, there’s more than thirty houses in this here court, and there’s no less than eight rooms in every house; now there’s nine or ten people in some of the rooms, I knows, but just say four in every room and calculate what that there comes to.” I did, and found it, to my surprise, to be 960. “Well,” continued my informant, chuckling and rubbing his hands in evident delight at the result, “you may as well just tack a couple of hundred on to the tail o’ them for makeweight, as we’re not werry pertikler about a hundred or two one way or the other in these here places.”

A gang of sewer-flushers–employed by the city, unlike the toshers–in a London sewer late in the 19th century.

No trace has yet been found of the sewer-hunters prior to Mayhew’s encounter with them, but there is no reason to suppose that the profession was not an ancient one. London had possessed a sewage system since Roman times, and some chaotic medieval construction work was regulated by Henry VIII’s Bill of Sewers, issued in 1531. The Bill established eight different groups of commissioners and charged them with keeping the tunnels in their district in good repair, though since each remained responsible for only one part of the city, the arrangement guaranteed that the proliferating sewer network would be built to no uniform standard and recorded on no single map.

Thus it was never possible to state with any certainty exactly how extensive the labrynth under London was. Contemporary estimates ran as high as 13,000 miles; most of these tunnels, of course, were far too small for the toshers to entert, but there were at least 360 major sewers, bricked in the 17th century. Mayhew noted that these tunnels averaged a height of 3 feet 9 inches, and since 540 miles of the network was formally surveyed in the 1870s it does not seem too much to suggest that perhaps a thousand miles of tunnel was actually navigable to a determined man. The network was certainly sufficient to ensure that hundreds of miles of uncharted tunnel remained unknown to even the most experienced among the toshers.

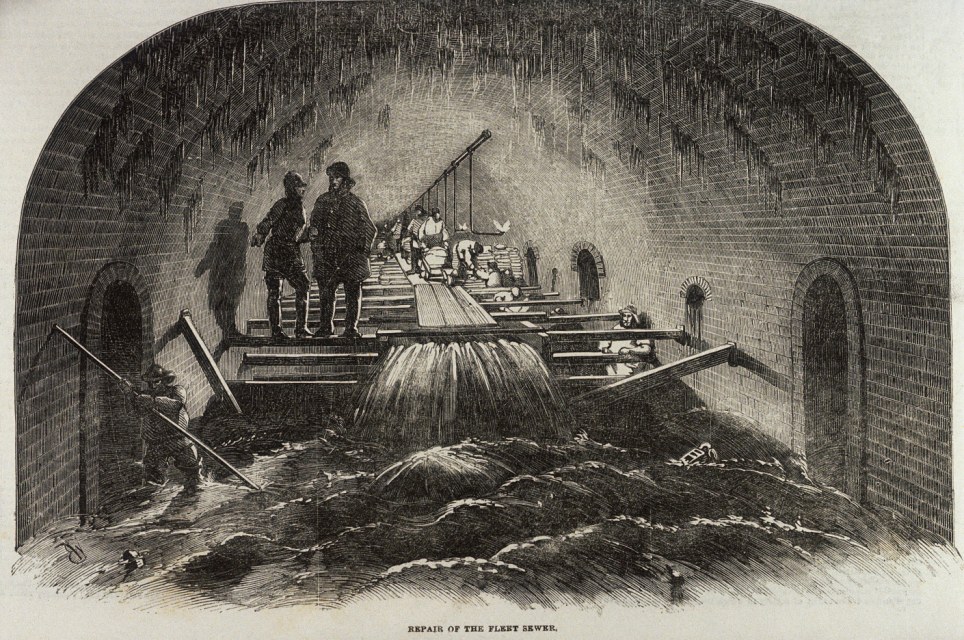

Sewer-flushers work one of the subterranean sluices that occasionally proved fatal to unwary toshers caught downstream of the unexpected flood.

It is hardly surprising, in these circumstances, that legends proliferated among the men who made a living in the tunnels. Mayhew recorded one of the most remarkable bits of folklore common among the toshers: that a “race of wild hogs” inhabited the sewers under Hampstead, in the far north of the city. This story–a precursor of the tales of “alligators in the sewers” heard in New York a century later–suggested that a pregnant sow

by some accident got down the sewer through an opening, and, wandering away from the spot, littered and reared her offspring in the drain; feeding on the offal and garbage washed into it continually. Here, it is alleged, the breed multiplied exceedingly, and have become almost as ferocious as they are numerous.

Thankfully, the same legend explained, the black swine that proliferated under Hampstead were incapable of traversing the tunnels to emerge by the Thames; the construction of the sewer network obliged them to cross Fleet Ditch–a bricked-over river–“and as it is the obstinate nature of a pig to swim against the stream, the wild hogs of the sewers invariably work their way back to their original quarters, and are thus never to be seen.”

A second myth, far more eagerly believed, told of the existence (Jacqueline Simpson and Jennifer Westwood record) “of a mysterious, luck-bringing Queen Rat”:

This was a supernatural creature whose true appearance was that of a rat; she would follow the toshers about, invisibly, as they worked, and when she saw one that she fancied she would turn into a sexy-looking woman and accost him. If he gave her a night to remember, she would give him luck in his work; he would be sure to find plenty of money and valuables. He would not necessarily guess who she was, for though the Queen Rat did have certain peculiarities in her human form (her eyes reflected light like an animal’s, and she had claws on her toes), he probably would not notice them while making love in some dark corner. But if he did suspect, and talked about her, his luck would change at once; he might well drown, or meet with some horrible accident.

Repairing the Fleet Sewer. This was one of the main channels beneath London, and carried the waters of what had once been a substantial river–until the expansion of the city caused it to be built over and submerged.

One such tradition was handed down in the family of a tosher named Jerry Sweetly, who died in 1890, and finally published more than a century later. According to this family legend, Sweetly had encountered the Queen Rat in a pub. They drank until midnight, went to a dance, “and then the girl led him to a rag warehouse to make love.” Bitten deeply on the neck (the Queen Rat often did this to her lovers, marking them so no other rat would harm them), Sweetly lashed out, causing the girl to vanish and reappear as a gigantic rat up in the rafters. From this vantage point, she told the boy: “You’ll get your luck, tosher, but you haven’t done paying me for it yet!”

Offending the Queen Rat had serious consequences for Sweetly, the same tradition ran. His first wife died in childbirth, his second on the river, crushed between a barge and the wharf. But, as promised by legend, the tosher’s children were all lucky, and once in every generation in the Sweetly family a female child was born with mismatched eyes–one blue, the other grey, the color of the river.

Queen Rats and mythical sewer-pigs were not the only dangers confronting the toshers, of course. Many of the tunnels they worked in were crumbling and dilapidated–“the bricks of the Mayfair sewer,” Peter Ackroyd says, “were said to be as rotten as gingerbread; you could have scooped them out with a spoon”–and they sometimes collapsed, entombing the unwary sewer hunters who disturbed them. Pockets of suffocating and explosive gases such as “sulphurated hydrogen” were also common, and no tosher could avoid frequent contact with all manner of human waste. The endlessly inquisitive Mayhew recorded that the “deposit” found in the sewers

has been found to comprise all the ingredients from the gas works, and several chemical and mineral manufactories; dead dogs, cats, kittens, and rats; offal from the slaughter houses, sometimes even including the entrails of the animals; street pavement dirt of every variety; vegetable refuse, stable-dung; the refuse of pig-styes; night-soil; ashes; rotten mortar and rubbish of different kinds.

Joseph Bazalgette’s new sewage system cleared the Thames of filth and saved the city from stench and worse, as well as providing London with a new landmark: The Embankment, which still runs along the Thames, was built to cover new super-sewers that carried the city’s effluent safely east toward the sea.

That the sewers of mid-19th-century London were foul is beyond question; it was widely agreed, Michelle Allen says, that the tunnels were “volcanoes of filth; gorged veins of putridity; ready to explode at any moment in a whirlwind of foul gas, and poison all those whom they failed to smother.” Yet this, the toshers themselves insisted, did not mean that working conditions under London were entirely intolerable. The sewers, in fact, had worked fairly efficiently for many years–not least because, until 1815, they were required to do little more than carry off the rains that fell in the streets. Before that date, the city’s latrines discharged into cesspits, not the sewer network, and even when the laws were changed, it took some years for the excrement to build up.

By the late 1840s, though, London’s sewers were deteriorating sharply, and the Thames itself, which received their untreated discharges, was effectively dead. By then it was the dumping-ground for 150 million tons of waste each year, and in hot weather the stench became intolerable; the city owes its present sewage network to the “Great Stink of London,” the infamous product of a lengthy summer spell of hot, still weather in 1858 that produced a miasma so oppressive that Parliament had to be evacuated. The need for a solution became so obvious that the engineer Joseph Bazalgette–soon to be Sir Joseph, a grateful nation’s thanks for his ingenious solution to the problem–was employed to modernize the sewers. Bazalgette’s idea was to build a whole new system of super-sewers that ran along the edge of the river, intercepted the existing network before it could discharge its contents, and carried them out past the eastern edge of the city to be processed in new treatment plants.

The exit of a London sewer before Bazalgette’s improvements, from Punch (1849). These outflows were the points through which the toshers entered the underground labrynth they came to know so well.

Even after the tunnels deteriorated and they became increasingly dangerous, though, what a tosher feared more than anything else was not death by suffocation or explosion, but attacks by rats. The bite of a sewer rat was a serious business, as another of Mayhew’s informants, Jack Black–the “Rat and Mole Destroyer to Her Majesty”–explained.”When the bite is a bad one,” Black said, “it festers and forms a hard core in the ulcer, which throbs very much indeed. This core is as big as a boiled fish’s eye, and as hard as stone. I generally cuts the bite out clean with a lancet and squeezes…. I’ve been bitten nearly everywhere, even where I can’t name to you, sir.”

There were many stories, Henry Mayhew concluded, of toshers’ encounters with such rats, and of them “slaying thousands… in their struggle for life,” but most ended badly. Unless he was in company, so that the rats dared not attack, the sewer-hunter was doomed. He would fight on, using his hoe, “till at last the swarms of the savage things overpowered him.” Then he would go down fighting, his body torn to pieces and the tattered remains submerged in untreated sewage, until, a few days later, it became just another example of the detritus of the tunnels, drifting toward the Thames and its inevitable discovery by another gang of toshers–who would find the remains of their late colleague “picked to the very bones.”

Sources

Peter Ackroyd. London Under. London: Vintage, 2012; Michele Allen. Cleansing the City: Sanitary Geographies in Victorian London. Athens : Ohio University Press, 2008; Thomas Boyle. Black Swine in the Sewers of Hampstead: Beneath the Surface of Victorian Sensationalism. London: Viking, 1989; Stephen Halliday. The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazelgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1999; ‘A London Antiquary’. A Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant and Vulgar Words… London: John Camden Hotten, 859; Henry Mayhew. London Characters and Crooks. London: Folio, 1996; Liza Picard. Victorian London: The Life of a City, 1840-1870. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005; Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson. The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, from Spring-Heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys. London: Penguin, 2005.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)