Racing the Storm: The Story of the Mobile Bay Sailing Disaster

When hurricane-force winds suddenly struck the Bay, they swept more than 100 boaters into one of the worst sailing disasters in modern American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/d7/8fd7f047-a084-4e32-a01b-a9ceec77b452/julaug2017_a07_disasteratsea.jpg)

The morning of April 25, 2015, arrived with only a whisper of wind. Sailboats traced gentle circles on Alabama’s Mobile Bay, preparing for a race south to the coast.

On board the Kyla, a lightweight 16-foot catamaran, Ron Gaston and Hana Blalack practiced trapezing. He tethered his hip harness to the boat, then leaned back over the water as the boat tilted and the hull under their feet went airborne.

“Physics,” he said, grinning.

They made an unusual crew. He was tall and lanky, 50 years old, with thinning hair and decades of sailing experience. She was 15, tiny and pale and redheaded, and had never stepped on a sailboat. But Hana trusted Ron, who was like a father to her. And Ron’s daughter, Sarah, was like a sister.The Dauphin Island Regatta first took place more than half a century ago and hasn’t changed much since. One day each spring, sailors gather in central Mobile Bay and sprint 18 nautical miles south to the island, near the mouth of the bay in the Gulf of Mexico. There were other boats like Ron’s, Hobie Cats that could be pulled by hand onto a beach. There were also sleek, purpose-built race boats with oversized masts—the nautical equivalent of turbocharged engines—and great oceangoing vessels with plush cabins belowdecks. Their captains were just as varied in skill and experience.

A ripple of discontent moved through the crews as the boats circled, waiting. The day before, the National Weather Service had issued a warning: “A few strong to severe storms possible on Saturday. Main Threat: Damaging wind.”

Now, at 7:44 a.m., as sailors began to gather on the bay for a 9:30 start, the yacht club’s website posted a message about the race in red script:

“Canceled due to inclement weather.” A few minutes later, at 7:57 a.m., the NWS in Mobile sent out a message on Twitter:

Don't let your guard down today - more storms possible across the area later this afternoon! #mobwx #alwx #mswx #flwx

— NWS Mobile (@NWSMobile) April 25, 2015

But at 8:10 a.m., strangely, the yacht club removed the cancellation notice, and insisted the regatta was on.

All told, 125 boats with 475 sailors and guests had signed up for the regatta, with such a variety of vessels that they were divided into several categories. The designations are meant to cancel out advantages based on size and design, with faster boats handicapped by owing race time to slower ones. The master list of boats and their handicapped rankings is called the “scratch sheet.”

Gary Garner, then commodore of the Fairhope Yacht Club, which was hosting the regatta that year, said the cancellation was an error, the result of a garbled message. When an official on the water called into the club’s office and said, “Post the scratch sheet,” Garner said in an interview with Smithsonian, the person who took the call heard, “Scratch the race” and posted the cancellation notice. Immediately the Fairhope Yacht Club received calls from other clubs around the bay: “Is the race canceled?”

“‘No, no, no, no,’” Garner said the Fairhope organizers answered. “‘The race is not canceled.’”

The confusion delayed the start by an hour.

A false start cost another half-hour, and the boats were still circling at 10:45 a.m. when the NWS issued a more dire prediction for Mobile Bay: “Thunderstorms will move in from the west this afternoon and across the marine area. Some of the thunderstorms may be strong or severe with gusty winds and large hail the primary threat.”

Garner said later, “We all knew it was a storm. It’s no big deal for us to see a weather report that says scattered thunderstorms, or even scattered severe thunderstorms. If you want to go race sailboats, and race long-distance, you’re going to get into storms.”

The biggest, most expensive boats had glass cockpits stocked with onboard technology that promised a glimpse into the meteorological future, and some made use of specialized fee-based services like Commanders’ Weather, which provides custom, pinpoint forecasts; even the smallest boats carried smartphones. Out on the water, participants clustered around their various screens and devices, calculating and plotting. People on the Gulf Coast live with hurricanes, and know to look for the telltale rotation on weather radar. April is not hurricane season, of course, and this storm, with deceptive straight-line winds, didn’t take that shape.

Only eight boats withdrew.

On board the Razr, a 24-foot boat, 17-year-old Lennard Luiten, his father and three friends scrutinized incoming weather reports in granular detail: The storm appeared likely to arrive at 4:15 p.m., they decided, which should give them time to run down to Dauphin Island, cross the finish line, spin around, and return to home port before the front arrived.

Just before a regatta starts, a designated boat carrying race officials deploys flag signals and horn blasts to count down the minutes. Sailors test the wind and jockey for position, trying to time their arrival at the starting line to the final signal, so they can carry on at speed.

Lennard felt thrilled as the moment approached. He and his father, Robert, had bought the Razr as a half-sunk lost cause, and spent a year rebuilding it. Now the five crew members smiled at each other. For the first time, they agreed, they had the boat “tuned” just right. They timed their start with precision—no hesitation at the line—then led the field for the first half-hour.

The small catamarans were among the fastest boats, though, and the Kyla hurtled Hana and Ron forward. On the open water Hana felt herself relax. “Everything slowed down,” she said. She and Ron passed a 36-foot monohull sailboat called the Wind Nuts, captained by Ron’s lifelong friend Scott Godbold. “Hey!” Ron called out, waving.

Godbold, a market specialist with an Alabama utility company whose grandfather taught him to sail in 1972, wasn’t racing, but he and his wife, Hope, had come to watch their son Matthew race and to help out if anyone had trouble. He waved back.

Not so long ago, before weather radar and satellite navigation receivers and onboard computers and racing apps, sailors had little choice but to be cautious. As James Delgado, a maritime historian and former scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, puts it, they gave nature a wider berth. While new information technology generally enhances safety, it can, paradoxically, bring problems of its own, especially when its dazzling precision encourages boaters to think they can evade danger with minutes to spare. Today, Delgado says, “sometimes we tickle the dragon’s tail.” And the dragon may be stirring, since many scientists warn that climate change is likely to increase the number of extraordinary storms.

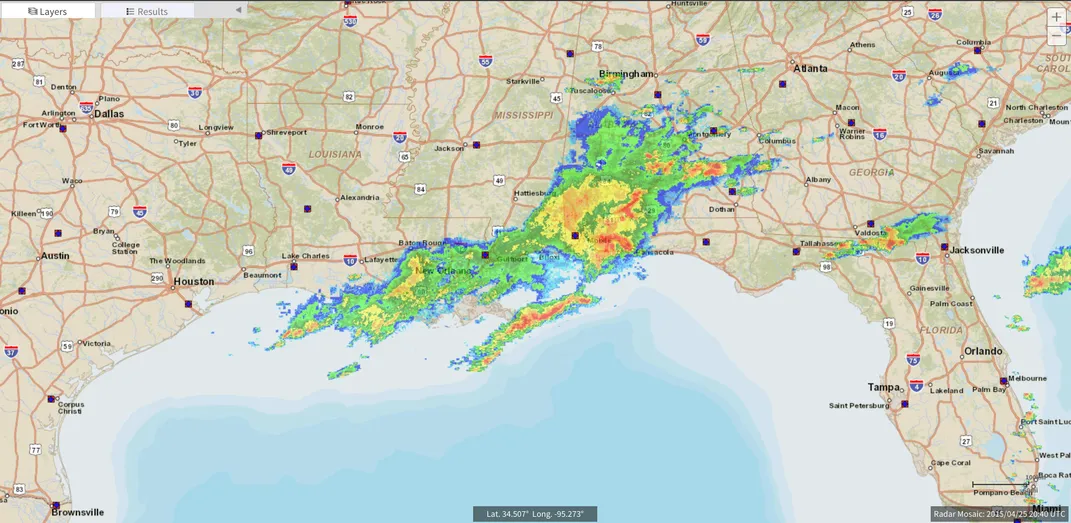

Within a few hours of the start of the 2015 Dauphin Island Regatta, as boats were still streaking for the finish line, the storm front reached the port of Pascagoula, Mississippi, 40 miles southwest of Mobile. It slammed into the side of the Manama, a 600-foot oil tanker weighing almost 57,000 tons, and heaved it aground.

**********

Mobile Bay, about 30 miles long and half as wide, is fed from the north by five rivers, so that depending on the tide and inland rains, the bay smells some days of sea salt, and others of river silt. A deep shipping channel runs up its center, but much of the bay is so shallow an adult could stand on its muddy bottom. On the northwestern shore stands the city of Mobile, dotted with shining high-rises. South of the city is a working waterfront—shipyards, docks. Across the bay, on the eastern side, a high bluff features a string of picturesque towns: Daphne, Fairhope, Point Clear. To the south, the mouth of the bay is guarded by Dauphin Island and Fort Morgan peninsula. Between them a gap of just three miles of open water leads into the vast Gulf of Mexico.

During the first half of the race, Hana and Ron chased his brother, Shane Gaston, who sailed on an identical catamaran. Halfway through the race he made a bold move. Instead of sailing straight toward Dauphin Island—the shortest route—he tacked due west to the shore, where the water was smoother and better protected, and then turned south.

It worked. “We’re smoking!” he told Hana.

Conditions were ideal at that point, about noon, with high winds but smooth water. About 2 p.m., as they arrived at the finish line, the teenager looked back and laughed. Ron’s brother was a minute behind them.

“Hey, we won!” she said.

Typically, once crews finish the race they pull into harbor at Dauphin Island for a trophy ceremony and a night’s rest. But the Gaston brothers decided to turn around and sail back home, assuming they’d beat the storm; others made the same choice. The brothers headed north along the bay’s western shore. During the race Ron had used an out-of-service iPhone to track their location on a map. He slipped it into a pocket and sat back on the “trampoline”—the fabric deck between the two hulls.

Shortly before 3 p.m., he and Hana watched as storm clouds rolled toward them from the west. A heavy downpour blurred the western horizon, as though someone had smudged it with an eraser. “We may get some rain,” Ron said, with characteristic understatement. But they seemed to be making good time—maybe they could make it to the Buccaneer Yacht Club, he thought, before the rain hit.

Hana glanced again and again at a hand-held GPS and was amazed at the speeds they were clocking. “Thirteen knots!” she told Ron. Eventually she looped its cord around her neck so she could keep an eye on it, then tucked the GPS into her life preserver so she wouldn’t lose it.

By now the storm, which had first come alive in Texas, had crossed three states to reach the western edge of Mobile Bay. Along the way it developed three separate storm cells, like a three-headed Hydra, each dense with cold air and icy particulates held aloft by a warm updraft, like a hand cradling a water balloon. Typically a cold mass will simply dissipate, but sometimes as a storm moves across a landscape something interrupts the supporting updraft. The hand flinches, and the water balloon falls: a downburst, pouring cold air to the surface. “That by itself is not an uncommon phenomenon,” says Mark Thornton, a meteorologist and member of U.S. Sailing, a national organization that oversees races. “It’s not a tragedy, yet.”

During the regatta, an unknown phenomenon—a sudden shift in temperature or humidity, or the change in topography from trees, hills and buildings to a frictionless expanse of open water—caused all three storm cells to burst forth at the same moment, as they reached Mobile Bay. “And right on top of hundreds of people,” Thornton said. “That’s what pushes it to historic proportions.”

At the National Weather Service’s office in Mobile, meteorologists watched the storm advance on radar. “It really intensified as it hit the bay,” recalled Jason Beaman, the meteorologist in charge of coordinating the office’s warnings. Beaman noted the unusual way the storm, rather than blow itself out quickly, kept gaining in strength. “It was an engine, like a machine that keeps running,” he said. “It was feeding itself.”

Storms of this strength and volatility epitomize the dangers posed by a climate that may be increasingly characterized by extreme weather. Thornton said that it wouldn’t be “scientifically appropriate” to attribute any storm to climate change, but said “there is a growing consensus that climate change is increasing the frequency of severe storms.” Beaman suggests more research should be devoted to better understanding what’s driving individual storms. “The technology we have just isn’t advanced enough right now to give us the answer,” he said.

On Mobile Bay, the downbursts sent an invisible wave of air rolling ahead of the storm front. This strange new wind pushed Ron and Hana faster than they had gone during any point in the race.

“They’re really getting whipped around,” he told a friend. “This is how they looked during Katrina.”

A few minutes later the MRD’s director called from Dauphin Island. “Scott, you’d better get some guys together,” he said. “This is going to be bad. There are boats blowing up onto the docks here. And there are boats out on the bay.”

The MRD maintains a camera on the Dauphin Island Bridge, a three-mile span that links the island to the mainland. At about 3 p.m., the camera showed the storm’s approach: whitecaps foaming as wind came over the bay, and beyond that rain at the far side of the bridge. Forty-five seconds later, the view went completely white.

Under the bridge, 17-year-old Sarah Gaston—Ron’s daughter, and Hana’s best friend—struggled to control a small boat with her sailing partner, Jim Gates, a 74-year-old family friend.

“We just were looking for any land at that point,” Sarah said later. “But everything was white. We couldn’t see land. We couldn’t even see the bridge.”

The pair watched the jib, a small sail at the front of the boat, ripping in slow motion, as if the hands of some invisible force tore it from left to right.

Farther north, the Gaston brothers on their catamarans were getting closer to the Buccaneer Yacht Club, on the bay’s western shore.

Lightning crackled. “Don’t touch anything metal,” Ron told Hana. They huddled on the center of their boat’s trampoline.

Sailors along the edges of the bay had reached a decisive moment. “This is the time to just pull in to shore,” Thornton said. “Anywhere. Any shore, any gap where you could climb on to land.”

Ron tried. He scanned the shore for a place where his catamaran could pull in, if needed. “Bulkhead...bulkhead...pier...bulkhead,” he thought. The walled-off western side of the bay offered no harbor. Less than two miles behind, his brother Shane, along with Shane’s son Connor, disappeared behind a curtain of rain.

“Maybe we can outrun it,” Ron told Hana.

But the storm was charging toward them at 60 knots. The world’s fastest boats—giant carbon fiber experiments that race in the America’s Cup, flying on foils above the water, requiring their crew to wear helmets—couldn’t outrun this storm.

Lightning flickered in every direction now, and within moments the rain caught up. It came so fast, and so dense, that the world seemed reduced to a small gray room, with no horizon, no sky, no shore, no sea. There was only their boat, and the needle-pricks of rain.

The temperature tumbled, as the downbursts cascaded through the atmosphere. Hana noticed the sudden cold, her legs shaking in the wind.

Then, without warning, the gale dropped to nothing. No wind. Ron said, “What in the wor”—but a spontaneous roar drowned out his voice. The boat shuddered and shook. Then a wall of air hit with a force unlike anything Ron had encountered in a lifetime of sailing.

The winds rose to 73 miles per hour—hurricane strength—and came across the bay in a straight line, like an invisible tsunami. Ron and Hana never had a moment to let down their sails.

The front of the Kyla rose up from the water, so that it stood for an instant on its tail, then flipped sideways. The bay was only seven feet deep at that spot, so the mast jabbed into the mud and snapped in two.

Hana flew off, hitting her head on the boom, a horizontal spar attached to the mast. Ron landed between her and the boat, and grabbed her with one hand and a rope attached to the boat with the other.

The boat now lay in the water on its side, and the trampoline—the boat’s fabric deck—stood vertical, and caught the wind like a sail. As it blew away, it pulled Ron through the water, away from Hana, stretching his arms until he faced a decision that seemed surreal. In that elongated moment, he had two options: He could let go of the boat, or Hana.

He let go of the boat, and in seconds it blew away beyond the walls of their gray room. The room seemed to shrink with each moment. Hana extended an arm and realized she couldn’t see beyond her own fingers. She and Ron both still wore their life jackets, but eight-foot swells crashed on them, threatening to separate them, or drown them on the surface.

The two wrapped their arms around each other, and Hana tucked her head against Ron’s chest to find a pocket of air free from the piercing rain.

In the chaos, Ron thought, for a moment, of his daughter. But as he and Hana rolled together like a barrel under the waves, his mind went blank and gray as the seascape.

Sarah and Jim’s boat had also risen up in the wind and bucked them into the water.

The mast snapped, sending the sails loose. “Jim!” Sarah cried out, trying to shift the sails. Finally, they found each other, and dragged themselves back into the wreckage of their boat.

About 30 miles north, a Coast Guard ensign named Phillip McNamara stood his first-ever shift as duty officer. As the storm bore down on Mobile Bay, distress calls came in from all along the coast: from sailors in the water, people stranded on sandbars, frantic witnesses on land. Several times he rang his superior, Cmdr. Chris Cederholm, for advice about how to respond, each time with increasing urgency.

**********

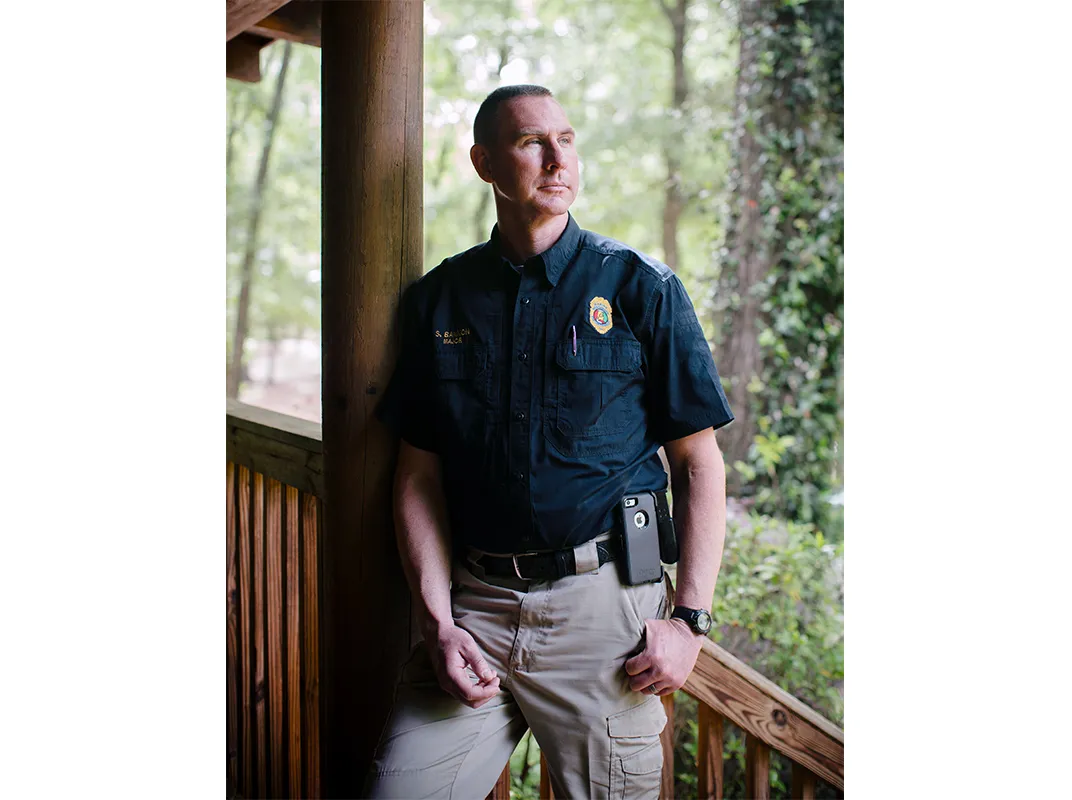

About 15 miles inland, Scott Bannon, a major with Alabama’s Marine Resources Division, looked up through the high windows in his log home west of Mobile. Bannon lives on a pine-covered hill and has seen so many hurricanes blow through that he can measure their strength by the motion of the treetops.

“By the third call it was clear something big was happening,” Cederholm said recently. When Cederholm arrived at the station, he understood the magnitude of the disaster—scores of people in the water—and he triggered a Coast Guard protocol called a “Mass Rescue Operation,” summoning a response from air, land and sea.

As authorities scrambled to grasp the scale of the storm, hundreds of sailors on the bay struggled to survive it. The wind hit the Luitens’ Razr so fast it pinned the sails to the mast; there was no way to lower them. The wind flipped the boat, slinging the crew—Lennard, his father, Robert, 71-year-old Jimmie Brown, and teenage friends Adam Clark and Jacob Pouncey—into the water. Then the boat barrel-rolled, and Lennard and Brown were briefly scooped back onto its deck before the keel snapped and they were tossed once again, this time in the other direction.

Brown struggled in a raincoat. Lennard, a strong swimmer, swam around the boat, searching for his dad, whom he found with Jacob. After 20 minutes or so, towering eight-foot waves threatened to drown them, and Lennard struck out for the shore to find help.

Normally, a storm’s hard edge blows past in two or three minutes; this storm continued for 45 minutes.

An experienced sailor named Larry Goolsby, captain of a 22-foot boat named Team 4G, was in sight of the finish line when the storm came on; he and two crew members had just moments to ease the sails before the wind hit. The gale rolled the boat over twice, before a much heavier 40-foot vessel hove into view upwind. The bigger boat was moving with all the force of the storm at its back, and bearing down on the three men.

One shouted over the wind, “They’re going to hit us!” just as the bigger boat smashed into the Team 4G, running it over and dragging the smaller boat away.

The crew members had managed to jump clear into the water just before impact. In the same instant, Goolsby grabbed a rope dangling from the charging boat and swung himself up onto its deck. Reeling, he looked back to see his crew mates in the water, growing more distant by the second. None were wearing life jackets. Goolsby snatched a life ring from the deck of the runaway vessel and dove back into the water, hoping to save his friends.

Similar crises unfolded across the bay. A 26-foot boat named the Scoundrel had finished the race and turned north when the storm hit. The wind knocked the boat on its side before the captain had time to let down the sails. As the boat lay horizontal, he leaped into the water, let loose the sails, and then scrambled back aboard as the ship righted itself. But one crew member, he saw, 27-year-old Kristopher Beall, had fallen in, and was clinging to a rope trailing the boat. The 72-year-old captain tried to haul him in as Beall gasped for air amid the waves.

**********

A dozen Coast Guard ships from Mississippi to Florida responded, along with several airplanes, helicopters and a team of searchers who prowled the coastline on all-terrain vehicles. People on horses searched the bay’s clay banks for survivors.

At the Coast Guard outpost on Dauphin Island, Bannon, the marine resources officer, made call after call to the families and friends of boat owners and captains, trying to work out how many people might be missing. The regatta organizers kept a tally of captains, but not of others who were on board the boats.

Cederholm, the Coast Guard commander, alerted the military chain of command, all the way up to three-star admiral William Lee. “I’ve never seen anything like this,” the 34-year veteran of the sea told Cederholm.

Near the Dauphin Island Bridge, a Coast Guard rescue boat picked up Sarah Gaston and Jim Gates. She had suffered a leg injury and hypothermia, and as her rescuers pulled her onto their deck, she went into shock.

Ron and Hana were closer to the middle of the bay, where the likelihood of rescue was frighteningly low. “All you can really see above water is someone’s head,” Bannon explained later. “A human head is about the size of a coconut. So you’re on a ship that’s moving, looking for a coconut bobbing between waves. You can easily pass within a few feet and never see someone in the water.”

Ron and Hana had now been in the water for two hours. They tried to swim for shore, but the waves and current locked them in place. To stave off the horror of their predicament, Hana made jokes. “I don’t think we’re going to make it home for dinner,” she said.

“Look,” Ron said, pulling the phone from his pocket. Even though it was out of service, he could still use it to make an emergency call. At the same moment, Hana pulled the GPS unit from her life jacket and held it up.

Ron struggled with wet fingers to dial the phone. “Here,” he said, handing it to Hana. “You’re the teenager.”

She called 911. A dispatcher answered: “What is your emergency and location?”

“I’m in Mobile Bay,” Hana said.

“The bay area?”

“No, ma’am. I’m in the bay. I’m in the water.”

Using the phone and GPS, and watching the blue lights of a patrol boat, Hana guided rescuers to their location.

As an officer pulled her from the water and onto the deck, the scaffolding of Hana’s sense of humor started to collapse. She asked, “This boat isn’t going to capsize too, is it?”

Ron’s brother and nephew, Shane and Connor, had also gone overboard. Three times the wind flipped their boat on its side before it eventually broke the mast. They used the small jib sail to fight their way toward the western shore. Once on land, they knocked on someone’s door, borrowed a phone, and called the Coast Guard to report that they’d survived.

The three-man crew of the Team 4G clung to their commandeered life ring, treading water until they were rescued.

Afterward, the Coast Guard hailed several volunteer rescuers who helped that day, including Scott Godbold, who had come out with his wife, Hope, to watch their son Matthew. As the sun started to set that evening, the Godbolds sailed into the Coast Guard’s Dauphin Island station with three survivors.

“It was amazing,” said Bannon. The odds against finding even one person in more than 400 square miles of choppy sea were outrageous. Behind Godbold’s sailboat, they also pulled a small inflatable boat, which held the body of Kristopher Beall.

After leaving Hope and the survivors at the station, Godbold was joined by his father, Kenny, who is in his 70s, and together they stepped back onto their boat to continue the search. Scott had in mind a teenager he knew: Lennard Luiten, who remained missing. Lennard’s father had been found alive, as had his friend Jacob. But two other Razr crew members—Jacob’s friend, Adam, and Jimmie Brown—had not survived.

By this point Lennard would have been in the water, without a life jacket, for six hours. Night had come, and the men knew the chances of finding the boy were vanishingly remote. Scott used the motor on his boat to ease out into the bay, listening for any sound in the darkness.

Finally, a voice drifted over the water: “Help!”

Hours earlier, as the current swept Lennard toward the sea, he had called out to boat after boat: a Catalina 22 racer, another racer whom Lennard knew well, a fisherman. None had heard him. Lennard swam toward an oil platform at the mouth of the bay, but the waves worked against him, and he watched the platform move slowly from his south to his north. There was nothing but sea and darkness, and still he hoped: Maybe his hand would find a crab trap. Maybe a buoy.

Now Kenny shined a flashlight into his face, and Scott said, “Is that you, Lennard?”

**********

Ten vessels sank or were destroyed by the storm, and 40 people were rescued from the water. A half-dozen sailors died: Robert Delaney, 72, William Massey, 67, and Robert Thomas, 50, in addition to Beall, Brown and Clark.

It was one of the worst sailing disasters in American history.

Scott Godbold doesn’t talk much about that day, but it permeates his thoughts. “It never goes away,” he said recently.

The search effort strained rescuers. Teams moved from one overturned boat to another, where they would knock on the hull and listen for survivors, before divers swam underneath to check for bodies. Cederholm, the Coast Guard commander, said that at one point he stepped into his office, shut the door and tried to stifle his emotions.

Working with the Coast Guard, which is currently investigating the disaster, regatta organizers have adopted more stringent safety measures, including keeping better records of boat crew and passenger information during races. The Coast Guard also determined that people died because they couldn’t quickly find their life preservers, which were buried under other gear, so it now requires racers to wear life jackets during the beginning of the race, on the assumption that even if removed, recently worn preservers will be close enough at hand.

Garner, the Fairhope Yacht Club’s former commodore, was dismissive of the Coast Guard’s investigation. “I’m assuming they know the right-of-way rules,” he said. “But as far as sailboat racing, they don’t know squat.”

Like many races in the U.S., the regatta was governed by the rules of U.S. Sailing, whose handbook for race organizers is unambiguous: “If foul weather threatens, or there is any reason to suspect that the weather will deteriorate (for example, lightning or a heavy squall) making conditions unsafe for sailing or for your operations, the prudent (and practical) thing to do is to abandon the race.” The manual outlines the responsibility of the group designated to run the race, known as the race committee, during regattas in which professionals and hobbyists converge: “The race committee’s job is to exercise good judgment, not win a popularity contest. Make your decisions based on consideration of all competitors, especially the least experienced or least capable competitors.”

The family of Robert Thomas is suing the yacht club for negligence and wrongful death. Thomas, who worked on boats for Robert Delaney, doing carpentry and cleaning jobs, had never stepped foot on a boat in water, but was invited by Delaney to come along for the regatta. Both men died when the boat flipped over and pinned them underneath.

Omar Nelson, an attorney for Thomas’ family, likens the yacht club to a softball tournament organizer who ignores a lightning storm during a game. “You can’t force the players to go home,” he said. “But you can take away the trophy, so they have a disincentive.” The lawsuit also alleges that the yacht club did in fact initially cancel the race due to the storm, contrary to Garner’s claim about a misunderstanding about the scratch sheet, but that the organizers reversed their decision. The yacht club’s current commodore, Randy Fitz-Wainwright, declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation. The club’s attorney also declined to comment.

For its part, the Coast Guard, according to an internal memo about its investigation obtained by Smithsonian, notes that the race’s delayed start contributed to the tragedy. “This caused confusion among the race participants and led to a one-hour delay....The first race boats finished at approximately 1350. At approximately 1508, severe thunderstorms consisting of hurricane force winds and steep waves swept across the western shores of Mobile Bay.” The Coast Guard has yet to release its report on the disaster, but Cederholm said that, based on his experience as a search-and-rescue expert, “In general, the longer you have boats on the water when the weather is severe, the worse the situation is.”

For many of the sailors themselves, once their boats were rigged and they were out on the water, it was easy to assume the weather information they had was accurate, and that the storm would behave predictably. Given the access that racers had to forecasts that morning, Thornton, the meteorologist, said, “The best thing at that point would be to stay home.” But even when people have decent information, he added, “they let their decision-making get clouded.”

“We struggle with this,” said Bert Rogers, executive director of Tall Ships America, a nonprofit sail training association. “There is a tension between technology and the traditional, esoteric skills. The technology does save lives. But could it distract people and give them a false sense of confidence? That’s something we’re talking about now.”

**********

Hana, who had kept her spirits buoyed with jokes in the midst of the ordeal, said the full seriousness of the disaster only settled on her later. “For a year and a half I cried any time it rained really hard,” she said. She hasn’t been back on the water since.

Lennard went back to the water immediately. What bothers him most is not the power of the storm but rather the power of numerous minute decisions that had to be made instantly. He has re-raced the 2015 Dauphin Island Regatta countless times in his mind, each time making adjustments. Some are complex, and painful. “I shouldn’t have left Mr. Brown to go find my dad,” he said. “Maybe if I had stayed with him, he would be OK.”

He has concluded that no one decision can explain the disaster. “There were all these dominoes lined up, and they started falling,” he said. “Things we did wrong. Things Fairhope Yacht Club did wrong. Things that went wrong with the boat. Hundreds of moments that went wrong, for everyone.”

In April of this year, the regatta was postponed because of the threat of inclement weather. It was eventually held in late May, and Lennard entered the race again, this time with Scott Godbold’s son, Matthew.

During the race, somewhere near the middle of the bay, their boat’s mast snapped in high wind. Scott Godbold had shadowed them, and he pulled alongside and tossed them a tow line.

Lennard was still wearing his life preserver.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this story used the phrase “60 knots per hour.” A knot is already a measure of speed: one knot is 1.15 miles per hour.