Radio Activity: The 100th Anniversary of Public Broadcasting

Since its inception, public radio has had a crucial role in broadcasting history - from FDR’s “Fireside Chats” to the Internet Age

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lee-deForest-inventor-of-radio-631.jpg)

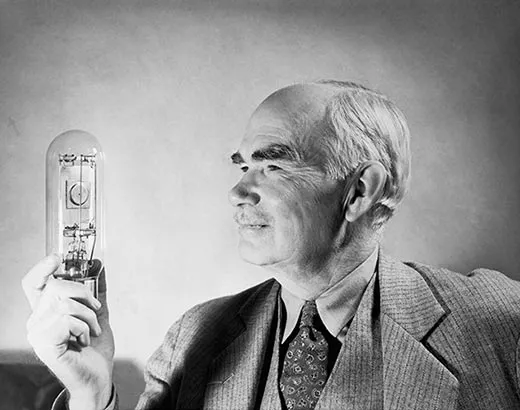

On January 13, 1910, tenor Enrico Caruso prepared to perform an entirely new activity: sing opera over the airwaves, broadcasting his voice from the Metropolitan Opera House to locations throughout New York City. Inventor Lee deForest had suspended microphones above the Opera House stage and in the wings and set up a transmitter and antenna. A flip of a switch magically sent forth sound.

The evening would usher out an old era—one of dot-dash telegraphs, of evening newspapers, of silent films, and of soap box corner announcements. In its place, radio communications would provide instant, long-distance wireless communication. In 2009, America celebrated the 40th anniversary of the creation of National Public Radio; thanks to deForest, 2010 marks the centennial of the true birth of the era of public broadcasting.

Wireless telephony had been several decades in the making. European experimenters (including Heinrich Hertz, for whom the radio frequency unit hertz is named) had contributed to the field in the late 1800s by experimenting with electromagnetic waves. In the 1890s, Guglielmo Marconi invented the vertical antenna, transmitting signals of ever-increasing distance; by 1901, he could send messages from England across the Atlantic Ocean to Newfoundland. Thanks in part to these advances, in December 1906, Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden was able to arrange a holiday broadcast to operators off the Atlantic seaboard. His singing, violin playing and biblical verse reading were heard on ships from New England to Virginia.

In the decade after deForest’s broadcast, popular interest in radio technology grew. Amateur devotees became known as “fans,” rather than “listeners” or “listeners-in,” which were terms used derogatorily to indicate that a person was not actively engaged in both sides of radio broadcast. “Every radio at the time—or all the good ones—could both transmit and receive,” explains Michele Hilmes, professor of media and cultural studies at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Radio was a highly technical leisure activity. Fans used wire coils and spark plugs as they built receivers and transmitters at home. Early radios required multiple dial adjustments.

Not everyone embraced the radio or understood how it functioned. The resulting mystery left some Americans wary. Were electromagnetic waves responsible for droughts? Skeptics blamed radios for the vibrations of bed springs, the creaking of floorboards, even a vomiting child. In Wisconsin, people thought radios could stop cows from producing milk, says Hilmes. Could the electromagnetic waves kill birds? Yes, Hilmes concurs: “If they flew into electrical wires.”

But critics could not dampen the spirits of radio fanatics. Despite a hiatus during World War I, when the government banned amateur radio broadcasting, the medium blossomed. In 1922, the United States made radio licenses available to broadcasters, and several hundred stations were founded.

The 1920s showed audiences that radio was a faster means of receiving updates than waiting for the newspaper. The experimental Detroit station 8MK announced the results of the 1920 Harding-Cox presidential election to the approximately 500 locals with receivers. (Others eager for speedy news gathered outside the Detroit News, which shared results by megaphone and lantern slide.) Also broadcast live were the oral arguments and verdict in the Scopes "Monkey Trial" of 1925.

As more events were captured on the radio, more fans built and bought sets. From 1922 to 1923, the number of radio sets in America increased from 60,000 to 1.5 million. In 1922, there were 28 stations in operation; by 1924, there were 1,400. Among the biggest commercial broadcasters were the National Broadcasting Company and the Columbia Broadcasting System, formed in 1926 and 1927, respectively, and still familiar as television networks NBC and CBS.

For noncommercial broadcasters, the precursor to what we today call public broadcasting, it was hard to stay afloat. Back in the 1920s, more than 200 colleges, universities, and other educational organizations had requested broadcasting licenses, but 75 percent of these stations folded by 1933. Hilmes points out that educational radio did particularly well in the Midwest, where stations could broadcast to land-grant college communities interested in agriculture. Still, in many regions, nonprofits struggled to maintain control of their bandwidth in the presence of companies using the new economic model for broadcasting: advertisement-based programming. Promotions for Pepsodent toothpaste and Ivory Soap sneaked their way into the living room between weather, news, sports and entertainment.

The Great Depression forced a lull in radio development, but still, by 1931, radio’s “Golden Age” had begun. Half of America’s homes had radios. Mothers listened in the morning, children after school, and fathers with their families during prime time broadcasts. Isolated rural citizens could listen to sermons and gospel music from their farmhouse kitchens. In 1932, the nation awaited updates about the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh’s baby. From their kitchen tables, starting on March 12, 1933, families could hear Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Sunday evening “Fireside Chats.”

During World War II, nine in ten families owned a radio, and they listened to an average of three to four hours of programming a day, using it as their main source of news. By 1940, over a quarter of American automobiles came with radios, ready for the early equivalent of today’s “driveway moments.”

Just as radio reached its zenith, a new industry took hold. According to Michael C. Keith, American radio scholar and associate professor of communication at Boston College, the 1950s began with the “fear that radio was finished as a consequence of television.” Radio had created dramas, sitcoms, soap operas—the same broadcasting genres that television now took for itself. As listeners became viewers, most in peril were educational and noncommercial radio. They relied on grants now directed to television alone. In 1964, the Ford Foundation, formerly the main funder of educational radio, completely cut its support.

But radio did not fold. In fact, it prospered. Keith cites several factors: The creation of the transistor allowed radios to become smaller and more mobile. Also, as radio stations studied demographic data, they were able to cater more specialized programming to their audiences. Perhaps most important, though, was the emergence of a new type of music. Keith credits rock ‘n’ roll with creating the youth culture in America, and as the music took to the airwaves, so did under-21 listeners.

Over the course of the next decade, interest grew in the idea of publicly funded broadcasting. President Lyndon Johnson had supported the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, which researched this question. When the committee recommended federal funding for television alone, several radio professionals agitated for the inclusion of “and radio” in the forthcoming bill. Indeed, Johnson’s 1967 Public Broadcasting Act established the federally funded Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which, in turn, created National Public Radio in 1969.

Over the next 40 years, NPR accumulated member stations nationwide. Commercial broadcasting also continued to flourish. Talk radio began to dominate the AM broadcast band, with music shifting to the clear FM band. In 1987, the Federal Communications Commission repealed the Fairness Doctrine, a 1949 policy that required broadcasters to show both sides of controversial issues; the repeal continues to buoy AM talk radio today. Eventually, the AM and FM bands were joined by XM and other satellite radio services, extending the medium’s reach in the 21st century.

What, then, is the future of radio? “Internet,” says Keith. “Brick–and-mortar has given way to cyberspace,” he says. Younger audiences no longer listen to traditional radio. Rather, “they are their own programmers.” Keith sees this coming decade as a time of transition, when radio stations will refine their Internet presence to be ready for the “terminus point,” not too far into the future, when their old-form broadcasts will fold.

We owe much of the continued success of public radio broadcasting—of all radio broadcasting, for that matter—to the efforts of deForest and his contemporaries. But there is a little bit more to the story of deForest’s 1910 endeavor. The truth is, when Lee deForest flipped the switch at the Metropolitan Opera House, during the first American public radio broadcast, audiences heard almost nothing. Static and radio interference muddled the music of Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci, the performances that evening. As Keith puts it, the “great self-promoter” deForest was “ultimately granted the title of Father of Radio, but with some reserve.” That night in 1910 gained significance mainly as a symbol. It marked the intended start of a century of broadcasting, a golden age of radio eventually eclipsed, mid-century, by the rise of a new box, the television.

Today, 100 years after deForest’s experiment, the Metropolitan Opera makes its performances available on the Internet, our modern-day wireless wonder. But listeners and fans alike can still hear the Met’s radio broadcasts on Saturday afternoon on NPR—and these days, the music is crystal clear.