The Raging Controversy at the Border Began With This Incident 100 Years Ago

In Nogales, Arizona, the United States and Mexico agreed to build walls separating their countries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/78/d078b1be-6fdf-4138-89de-70e840a60e2f/julaug2018_a09_prologue.jpg)

In early August 1918, Felix B. Peñaloza, the presidente municipal, or mayor, of Nogales, Mexico, ordered construction of a fence running along the boundary line between his city and Nogales, Arizona. The fence would consist of six wires strung to a height of six feet. His intent was to direct the flow of people crossing the border through two gateways, to make it easier for a growing number of soldiers, customs agents and other officials to oversee transborder movement. Peñaloza also met with U.S. representatives to discuss a second, parallel fence, to be built by the Americans. Mexican officials said they “would welcome the building of such a fence by the United States Government, as it would aid officials on both sides of the line in enforcing their regulations,” and they insisted that “such action would not be irritating or offensive to Mexican sentiment.”

Today a ten-mile-long rusted steel border wall is a defining feature of the cities. Its origin story begins with these two fences. When they were first erected in Nogales a century ago, they were neither a brazen political statement nor a barrier to immigrants, but a cooperative measure, embraced by both the United States and Mexico in the spirit of “good fences make good neighbors.” But the proposed American fence became what was most likely the first permanent barrier to control the movement of people across the U.S.-Mexico border.

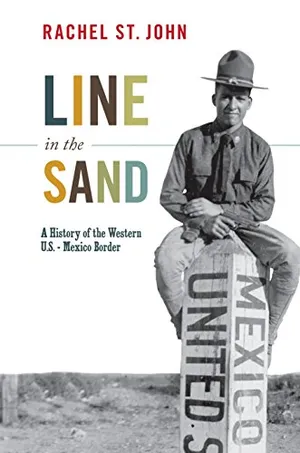

Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border (America in the World Book 11)

Drawing on extensive research in U.S. and Mexican archives, Line in the Sand weaves together a transnational history of how an undistinguished strip of land became the significant and symbolic space of state power and national definition that we know today.

Peñaloza’s fence cut through the heart of the twin cities of Nogales—known as Ambos Nogales, “Both Nogales.” Founded in 1882, Ambos Nogales became a bustling community centered on the boundary line, which ran along International Street. For years Mexicans and Americans crossed the border regularly to do business, shop, socialize and celebrate the holidays of both nations. Years later, former residents recalled how they had even played on the line as children.

Tensions along the border started to rise with the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, and were heightened by the First World War. A violent battle between opposing Mexican forces took place in Nogales, Mexico, in 1913. A second battle in the town two years later saw U.S. cavalrymen cross into Mexican territory to engage Pancho Villa’s troops, who had fired across the line. The wars also fueled worries about smugglers running guns into Mexico, refugees fleeing to the United States and international espionage in the borderlands.

The U.S. government had built its first border fence between 1909 and 1911—a barbed wire divide along the California border—to prevent cattle from wandering between the countries. Now, as both nations adopted new measures to monitor the border, more fences began to appear. Photographs seem to show one beside the customhouse near Tijuana and another along the border between Douglas, Arizona, and Agua Prieta, Mexico. These were likely temporary wartime measures, and as in Nogales, they were intended to prevent cross-border clashes.

But on August 27, 1918, soon after Mexican workers had erected the fence in Nogales, conflict broke out when an unidentified man attempted to cross into Mexico. A U.S. customs inspector ordered him to halt, but he did not stop. Officers on both sides of the border raised their guns, and a firefight broke out. About two hours later, at least 12 Mexicans and Americans had been killed, including Peñaloza, who had built the fence precisely to minimize the risk of conflict between the nations.

Ironically, despite his failure, U.S. officials in Nogales, Arizona, soon went ahead with plans for their own fence—which quickly became a model for controlling the movement of people across the U.S.-Mexico border. Following Nogales’ lead, officials in Calexico, California, erected a fence that ran two miles along the boundary line there. By the 1920s, fences were a fixture in most border towns.

Over time, the fences were put to a new use. In the 1940s, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service coordinated with the International Boundary and Water Commission to erect chain-link barriers on the border. More fences, a border patrolman later acknowledged, forced unauthorized migrants through dangerous mountains, deserts and rivers “around the ends of the fence.” The U.S. expansion of the fencing in the 1990s doubled-down on this strategy, leading to a dramatic increase in the number of migrants who died attempting the treacherous crossing. Thus the fences and other barriers that stand along much of the U.S.-Mexico border now mark not only an international boundary but also a humanitarian crisis.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.