The Raid on Bermuda That Saved the American Revolution

How colonial allies in the Caribbean pulled off a heist to equip George Washington’s Continental Army with gunpowder

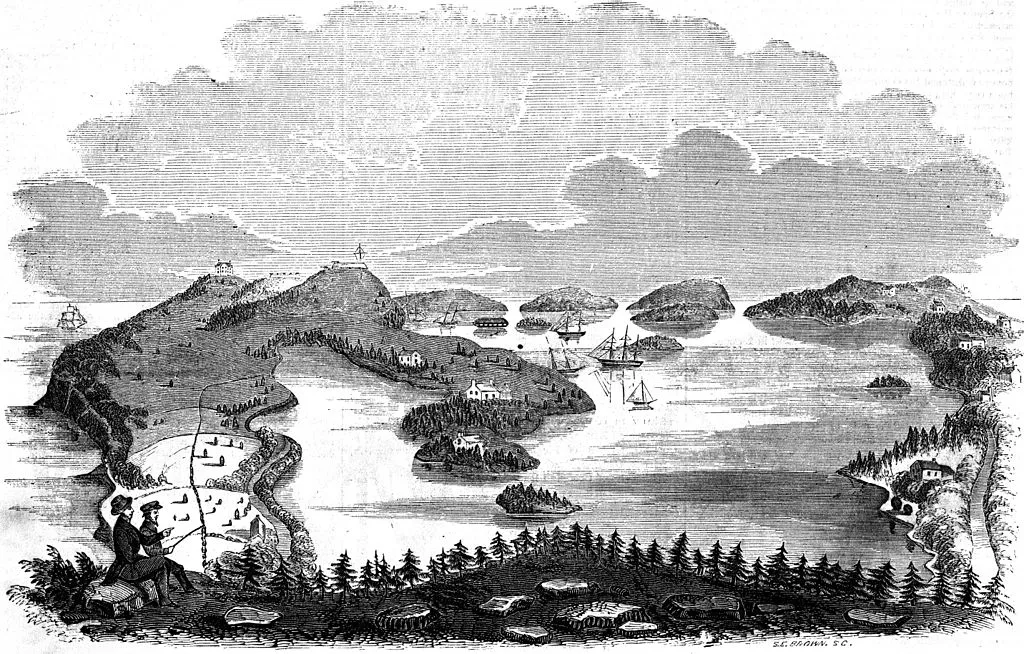

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/19/c5190e34-d0f7-4fc7-91b5-9b80061d6a23/granger_0009337_highres.jpg)

For most of 1775, Revolutionary troops under the command of George Washington had the British Army trapped in Boston, but it was hard to say who was at the mercy of whom. By July, after three months of skirmishes against the Redcoats, Washington's soldiers had only enough gunpowder for nine bullets per man. The year prior, as tensions in the colonies worsened, George III banned the import of firearms and gunpowder from Europe, and had been confiscating them in a bid to disarm the rebellion. The only American gunpowder mill, the Frankford Powder-Mill in Pennsylvania, wasn't producing enough to fight a war. Knowing their guns were close to becoming useless, the Americans began equipping themselves with wooden pikes and spears for hand-to-hand combat.

They needed gunpowder, however they could get it.

It was a lucky problem for Henry Tucker, a Bermudan merchant eager to find new business. The Continental Congress had announced an embargo against loyal British colonies, set to come into effect in September, and in July 1775, Tucker traveled to Philadelphia, where Congress met, to find some way out of it. Bermuda relied significantly on American food imports, and he argued as much for his business as for his belly. He'd noted a clause in the embargo that said ships carrying munitions to American ports would be allowed an exemption to trade with American colonies, regardless of their affiliation with the British.

As the Second Continental Congress met, Tucker schemed with Benjamin Franklin to help both of their causes. Two of Tucker's sons, living in South Carolina and Virginia, had freely talked about an unguarded magazine where the gunpowder cache was held, just north of Bermuda’s main town, St. George’s, and its existence was by now an open secret in the American colonies. Franklin, having heard about the gunpowder, told Tucker that Bermuda could bargain its way out of the embargo if he brought gunpowder for trade. Tucker didn't have gunpowder to offer, but he knew how to get it.

Since 1691, the colonial authorities in Bermuda had instituted a policy that required visiting ships to donate either money or gunpowder to the island every time they arrived, according to Dorcas Roberts, the director of preservation of the Bermuda National Trust, a historical preservation charity. Over the years that amounted to a great deal of gunpowder.

Tucker had written in a 1774 letter that the Americans were right to rebel against the Crown, and that British rule was equal to slavery. Elsewhere and at other opportunities, he was open about his contempt of the British government. On the whole, his fellow Bermudans sympathized with the Americans, but living on a 20-square-mile speck 700 miles off North Carolina, they couldn't afford conflict with the British—the whole island could have been shut down by one British warship and an angry stare.

Tucker would need a lot of good, loyal men to liberate the gunpowder from its storehouse.

On the night of August 14 in St. George's, Tucker's conspirators met at the gunpowder magazine, while Bermuda’s Governor George James Bruere slept in his residence a half-mile away. Very much loyal to the Crown, Bruere was nonetheless family to the American-sympathizing, treasonous Tuckers: Tucker’s son, the one still living in Bermuda and acting as co-conspirator with his father, was married to Bruere's daughter.

Historians today can retrace what happened next thanks to a letter Bruere wrote to the secretary of state for the American colonies. “The powder magazine, in the dead of the night of the 14th of August… was broke into on Top, just to let a man down, and the Doors most Audaciously and daringly forced open, at great risk of their being blown up,” he wrote. Several conspirators crawled onto the roof and into an air vent so they could drop down into the storehouse. Accounts differ on whether they subdued a single guard, but it's unlikely it was guarded at all.

The gunpowder awaited the men in quarter-barrels – kegs – that held 25 pounds of gunpowder each, says Rick Spurling, of Bermuda's St. George's Foundation, a historical preservation nonprofit. The conspirators took 126 kegs, according to Captain James Wallace of the HMS Rose, who was engaged in the American theater, in a September 9 letter. That amounted to 3,150 pounds worth of gunpowder, enough to quadruple Washington's ammunition.

The conspirators’ next challenge? Silently moving the kegs without waking the whole population of St. George’s. Again, accounts differ. Many assume the Bermudans rolled the kegs, but they were working in the early hours of dark morning, a half-mile away from a sleeping governor with soldiers, ships and jails at his disposal. Rolling barrels would have been loud, and if they were only quarter barrels, then a man could easily carry one. Spurling believes that Tucker’s men walked the kegs straight up the hill behind town and down to Tobacco Bay, where an American ship, the Lady Catherine, weighed anchor.

The kegs were then ferried from shore to ship in pen-deck rowboats about 32 feet long. At dawn, as Bruere awoke, the Lady Catherine loaded the last of the gunpowder kegs; the magazine had been almost entirely cleared out. He saw the Lady Catherine and another American ship on the horizon, assumed correctly that his missing gunpowder was taking a vacation across the sea, and sent a customs ship to chase them down.

Bruere's post-raid letter identified the second ship as the Charleston and Savannah Packet, but the Americans wouldn't have needed two merchant ships to carry 126 kegs of gunpowder—one would have sufficed, and it was just coincidence that the Packet was there that morning. Nonetheless, Bruere's customs ship couldn't catch the escaping gunpowder, and it turned around, defeated. Bruere was furious and humiliated.

If the townspeople knew anything, they weren't telling him. He put out a reward for information, but had no takers. Even Bermuda's government was lackluster in its response. “There was an investigation and a committee of parliament, but it just didn't go anywhere,” says Spurling. “I think they had to show outrage, but by and large most were secretly quite happy with the deal Tucker made.”

No one was convicted, not even Tucker, says Diana Chudleigh, the historian who authored the most recent guidebook on Tucker's house, now a museum. Making good on their word, the American colonies allowed trade with Bermuda to continue for years. Bruere considered the Bermudans treasonous for trading with the Americans, and from 1778 to his death in 1780 he commissioned Loyalist privateers to raid American trade ships between the Colonies and Bermuda. Trade continued, though, for years after his death, until the ever-increasing number of privateers finally choked it to a halt in the later years of the war. Even Tucker gave up trading with the colonies, as unarmed merchants couldn't compete against government-sanctioned raiders.

As for Bermuda's gunpowder, enough of it eventually made its way to Washington's men at Boston. The British, unable to hold their position, evacuated the city in March of 1776. The Bermudan gunpowder supply lasted through the end of that campaign and into June, when it was used to defend Charleston from British invasion, according to Spurling. A port vital to the American war effort, losing Charleston could have choked the rebellion into submission. Outmanned five-to-one, American defenders fought off nine British warships. The British wouldn't try again for four years, all because a Bermudan governor left a storehouse unguarded, because who would ever dare try to heist so much gunpowder from a town in the middle of an ocean?