Reading the Writing on Pompeii’s Walls

To better understand the ancient Roman world, one archaeologist looks at the graffiti, love notes and poetry alike, left behind by Pompeians

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pompeii-street-graffiti-631.jpg)

Rebecca Benefiel stepped into the tiny dark room on the first floor of the House of Maius Castricius. Mosquitoes whined. Huge moths flapped around her head. And – much higher on the ick meter—her flashlight revealed a desiccated corpse that looked as if it was struggling to rise from the floor. Nonetheless, she moved closer to the walls and searched for aberrations in the stucco. She soon found what she was looking for: a string of names and a cluster of numbers, part of the vibrant graffiti chitchat carried on by the citizens of Pompeii before Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79 and buried their city in a light pumice stone called lapilli.

“There are a few hazards to this work,” laughs Benefiel, a 35-year old classicist from Washington and Lee University who has spent part of the past six summers in Pompeii. “Sometimes the guards forget to let me out of the buildings at the end of the day!”

Regardless, she’s always eager to return.

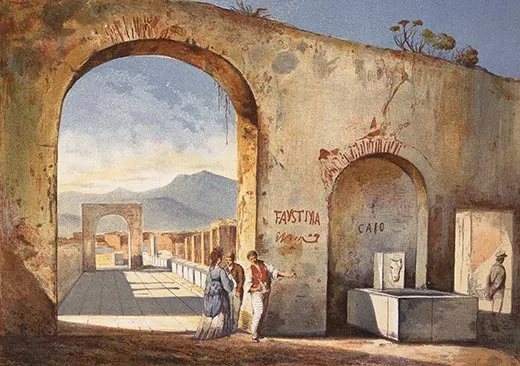

Vesuvius dumped ashes and lapilli on Pompeii for 36 hours, sealing the entire city up to an average height of 20 feet. Since the 18th century, archaeologists have excavated about two-thirds, including some 109 acres of public buildings, stores and homes. The city’s well-preserved first level has given archaeologists, historians and classicists an unparalleled view of the ancient world, brought to a halt in the middle of an ordinary day.

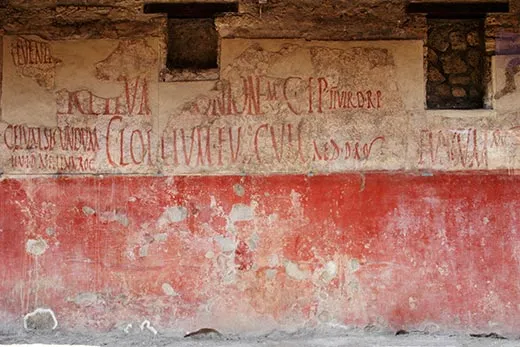

From the very beginning, archaeologists noticed copious amounts of graffiti on the outsides of buildings. In the late 1800s, scholars began making careful copies of Latin inscriptions throughout the ancient Roman world, including Pompeii, and cataloging them. This effort is a boon to scholars like Benefiel, since more than 90 percent of Pompeii’s recorded graffiti have since been erased by exposure to the elements.

Even though she studies this vast collection of inscriptions, Benefiel prefers to wander the ancient city and examine the remaining graffiti in context. Much of what remains is on protected interior walls, where servants, visitors and others took sharp instruments to the stucco and left their mark. “The graffiti would have been much more visible then than they are now,” she says. “Many of these walls were brightly painted and highly decorated, and the graffiti let the underlying white plaster show through.”

In the ancient Roman world, graffiti was a respected form of writing—often interactive – not the kind of defacement we now see on rocky cliffs and bathroom stalls. Inside elite dwellings like that of Maius Castricius—a four-story home with panoramic windows overlooking the Bay of Naples that was excavated in the 1960s—she’s examined 85 graffito. Some were greetings from friends, carefully incised around the edges of frescoes in the home’s finest room. In a stairwell, people took turns quoting popular poems and adding their own clever twists. In other places, the graffiti include drawings: a boat, a peacock, a leaping deer.

The 19th century effort to document ancient graffiti notwithstanding, scholars have historically ignored the phenomenon. The prevailing attitude was expressed by August Mau in 1899, who wrote, “The people with whom we should most eagerly desire to come into contact, the cultivated men and women of the ancient city, were not accustomed to scratch their names upon stucco or to confide their reflections and experiences to the surface of a wall.” But Benefiel’s observations show the opposite. “Everyone was doing it,” she says.

Contemporary scholars have been drawn to the study of graffiti, interested to hear the voices of the non-elite and marginal groups that earlier scholars spurned and then surprised to learn that the practice of graffiti was widespread among all groups across the ancient world. Today, graffiti is valued for the nuance it adds to our understanding of historical periods.

In the past four years, there have been four international conferences devoted to ancient and historic graffiti. One, at England’s University of Leicester organized by scholars Claire Taylor and Jennifer Baird in 2008, drew so many participants that there wasn’t space for all of them. Taylor and Baird have edited a book that sprang from that conference called Ancient Graffiti in Context, which will be published in September. On the book’s introductory page, an epigram taken from a wall in Pompeii speaks to the multitude of graffiti in the ancient world: “I’m amazed, O wall, that you have not fallen in ruins, you who support the tediousness of so many writers.”

“Graffiti is often produced very spontaneously, with less thought than Virgil or the epic poetry,” says Taylor, a lecturer in Greek history at Trinity College in Dublin. “It gives us a different picture of ancient society.”

Pablo Ozcáriz, a lecturer in ancient history at Madrid’s Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, has found thousands of medieval graffiti in the Cathedral of Pamplona and at the Abbey of La Olivia in Navarre. Taken as a whole, they often offer a more realistic underpinning to official histories. “It’s as if someone asks us to write two diaries,” Ozcáriz explains. “One will be published as a very important book and the other will be just for me. The first may be more beautiful, but the second will be more sincere.”

Benefiel’s study of Pompeii’s graffiti has revealed a number of surprises. Based on the graffiti found on both exterior walls and in kitchens and servant rooms, she surmises that the emperor Nero was much more popular than we tend to think (but not so much after he kicked his pregnant wife). She’s found that declarations of love were every bit as common then as they are today and that it was acceptable for visitors to carve their opinions about the city into its walls. She’s discovered that the people of Pompeii loved displaying their cleverness via graffiti, from poetry contests to playful recombinations of the letters that form Roman numerals.

And she’s found that Pompeians expressed far more goodwill than ill will. “They were much nicer in their graffiti than we are,” she says. “There are lots of pairings with the word ‘felicter,’ which means ‘happily.’ When you pair it with someone’s name, it means you’re hoping things go well for that person. There are lots of graffiti that say ‘Felicter Pompeii,’ wishing the whole town well.”