Get Reintroduced to Rosa Parks as a New Archive Reveals the Woman Behind the Boycott

The Rosa Parks collection adds depth to the story of the civil rights heroine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0b/e7/0be765c8-640a-45c2-a818-1123da05bfb1/dec2015_g01_phenom-web-resize.jpg)

I had been pushed around all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it any more.” Rosa Parks wrote those words just a short time after her famous refusal, 60 years ago this month, to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, city bus, a protest that galvanized a yearlong bus boycott and opened a new chapter in the struggle for American civil rights. The sentence appears in previously unseen notes in an archive of Parks’ personal papers that opened earlier this year and underscores a lesser-known dimension of her life: Far from being a meek seamstress who just happened to defy authorities that December evening, she was a fierce and persistent political activist nearly her whole life.

The Rosa Parks Collection had long been sequestered and unavailable to scholars because of a dispute over her estate and the collection’s hefty asking price. Finally, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation bought the archive and lent the 7,500 papers and 2,500 photographs to the Library of Congress for a decade. They contain letters, datebooks, financial documents and, perhaps most significantly, notes for speeches and other material that Parks apparently wrote during the boycott year and in the late 1950s. They reveal her intimate feelings about white supremacy in America and her belief in rebelling against it despite the costs. They also highlight the hardship that she and her family endured in the decade following the boycott.

Parks wrote poetically about how life under Jim Crow “walks us on a tightrope from birth”—demonizing so-called “troublemakers” and requiring a “major mental acrobatic feat” to survive. She cast the boycott not as an outgrowth of her singular experience but as a broad reaction to injustice; she noted the case of 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, who was arrested and manhandled on a Montgomery bus earlier that year, and the savage beating of a black Army veteran by a bus driver who was fined $25 and allowed to keep his job. In another shard of personal writing, she reframed her supposed crime: “Let us look at Jim Crow for the criminal he is and what he had done to one life multiplied millions of times over these United States and the world.”

Born in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1913, Parks was instilled with the will to fight. Her grandfather, a supporter of the black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, sat out with his shotgun to protect the family home from Ku Klux Klan violence, and sometimes 6-year-old Rosa would sit vigil with him. Later, she married Raymond Parks, a barber who was working to prevent the executions of the wrongfully accused Scottsboro boys; after joining the Montgomery NAACP, she spent much of the 1940s and early ’50s working alongside union activist E.D. Nixon to pursue justice for black victims of white brutality, register black voters and push for desegregation.

In 1956, five weeks into the bus boycott, Parks lost her job, and so did her husband. She spent the year traveling the country to raise attention and funds for the movement despite her family’s imperiled finances. Even after the boycott ended, neither Rosa nor Raymond could find steady work, and in August 1957, still receiving death threats, they left Montgomery for Detroit.

Parks said that she found “not too much difference” between the segregation and discrimination in Detroit and what she’d left behind in Montgomery. For the next five decades she fought racism in the North. She worked for Representative John Conyers, responding to constituents’ needs, and, calling Malcolm X her hero, took part in the growing black power movement; she served on prisoner-defense committees, showed up at scores of antiwar protests, spoke out for welfare and housing rights and volunteered for numerous black candidates.

She insisted to the end of her life in 2005 that the United States had a long way to go to address racial inequality. Yet our tributes to her often lose sight of her example and fail to see that the need for her kind of courage isn’t just a thing of the past. “Don’t give up,” Parks told students at Spelman College in 1985, “and don’t say the movement is dead!”

Related Reads

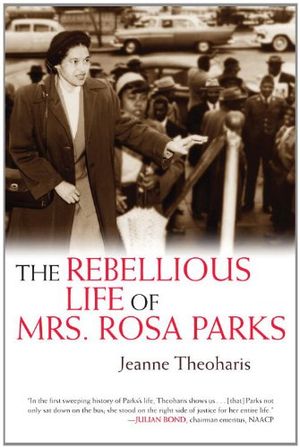

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks