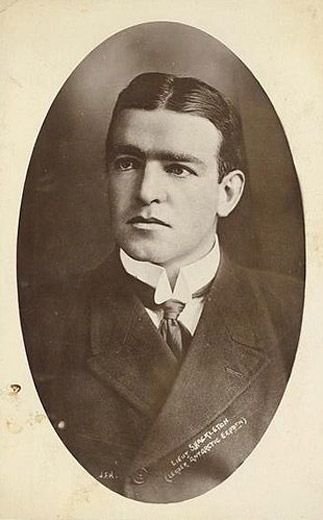

Reliving Shackleton’s Epic Endurance Expedition

Tim Jarvis’s Plan to Cross the Antarctic in an Exact Replica of the James Caird

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shackleton-james-caird-in-surf-631.jpg)

Legend has it that Antarctic adventurer Ernest Shackleton posted an advertisement in a London paper before his infamous Endurance expedition:

“Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.”

Although no one has been able to find the original ad, the sentiment, at the very least, should serve as a strong warning to Tim Jarvis, the British/Australian adventurer who is attempting to recreate the expedition as authentically as possible.

“For Shackleton it was a journey into the unknown made out of desperation,” Jarvis says. “For us it will not be that different.”

Shackleton was a leader of an era of polar exploration, but his misadventure began in 1915, when his ship sank just 15 months into the Antarctic journey, stranding him and 28 men. Their once-proud journey was reduced to a sad hamlet of windblown tents on the ice. Desperate, Shackleton and five others embarked on the 800-mile mission across the Southern Ocean in the James Caird, a dinky, 22.5-foot, oak-framed lifeboat. Seventeen days of frigid winds and treacherous seas later, they landed on the remote island of South Georgia where they clambered over the rocky, glaciated mountains to find refuge. It would take more than four months for Shackleton to return to Elephant Island and rescue the 23 men left behind. Despite the odds against them, all 28 survived.

It’s an astonishing journey that has yet to be authentically replicated. But in January, Jarvis and his crew will set out in a replica of the Caird and venture on the same 800-mile journey, titled the “Shackleton Epic,” and they plan on doing it exactly as Shackleton did—down to the reindeer skin sleeping bags and Plasmon biscuits.

In fact, the only concession to using period equipment will be modern emergency gear on board as stipulated by the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea.

When Jarvis commissioned the replica from master boat builder Nat Wilson, it was nothing short of a challenge—exact record of sail rig and hull construction does not exist—the only surviving reference is the boat itself, now on permanent display at Dulwich College in London. ‘Replicas’ of varying kinds exist from IMAX films and other mission reenactments, but according to Sebastian Coulthard, the Petty Officer aboard the Alexandra Shackleton, this lifeboat is the most accurate copy of the Caird ever constructed. All of the dimensions were taken from the original—at an accuracy of a quarter of an inch.

The original James Caird had an open top, exposing its inhabitants to the elements. All of the seams were caulked with wax and plugged with a blend of oil paint and seal blood. When the hatch was open and the waves were pouring in, the crew had very little protection from the sea.

Like the Caird, there is little legroom in the Alexandra Shackleton—the masts, spars and oars are tied to the rower’s seat. Damp and dank, the space available will be used more for supplies than the comfort of its inhabitants.

“It was extremely claustrophobic, cold and noisy [in the James Caird]. With the sounds of the waves on the hull, in rough sea it would’ve been like a washing machine,” Jarvis says. “The cold comes through the hull. The Southern Ocean’s temperatures range from 28 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit.”

There have been many attempts to trace Shackleton’s steps in the past, but the journey to South Georgia Island hasn’t become any less harrowing than it was 96 years ago. Trevor Potts, the leader of a 1994 expedition that recreated the James Caird journey with modern equipment, can vouch for that.

“The risks of such an expedition are very high,” Potts says. “It would be very easy to get swamped or rolled over. In severe weather in the open ocean, an escort ship would be very little help until the conditions moderated.”

On their journey, Potts and his crew fought gale winds up to 50 miles per hour across the Southern Ocean. They dropped anchor in South Georgia at a derelict whaling station—one of three used by hunters during Shackleton’s era. On land, faced with heavily crevassed terrain and little visibility, their attempt to retrace Shackleton’s mountaineering leg of the journey in reverse was halted. The following is an excerpt from Potts’s entry into a logbook at the Cumberland Bay station:

“Left to do Shackleton’s crossing both ways, not surprising we did not make it. Crossed the stream off the König [glacier] a bit deeper and very fast, not a pleasant experience. Chris nearly ruined a perfectly hideous pair of underpants with fear.”

Potts knows the list of risks with using period equipment is a long one: Crevasse fall, climbing injury, frostbite, exposure to the elements and capsizing—to name a few. Many of Shackleton’s men were frostbitten; records from those left on Elephant Island note the amputation of one man’s toe and part of an ear.

“Shackleton only had Burberry windproof clothing suitable for the dry, frozen continent. Once that type of clothing is wet, it will stay wet for the whole journey,” Potts says. “Shackleton and his men were hardened to it after a year on the ice and still some of them were more dead than alive when [the five men] returned [to Elephant Island].”

The key to making it through the journey in one piece—besides a healthy dose of luck—Jarvis says, is in the training of his crew. Prior to embarkation, they will complete crevasse rescue training and man-overboard drills and consult with other expert sailors.

“We will keep Shackleton’s story alive by attempting the journey. If successful, we will not claim to truly have done what he did, as our chances for rescue will be better than his were,” Jarvis says. “Nevertheless, we will have gotten as close as we can to doing what he did.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)