Remembering Resurrection City and the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968

Lenneal Henderson and thousands of other protesters occupied the National Mall for 42 days during the landmark civil rights protest

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/0e/710ecf61-e42f-4ccc-b8a3-6755dbe70e56/ap_6806240112-wr.jpg)

One day in early December 1967, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. laid out his vision for the Poor People’s Campaign, his next protest in Washington, D.C.,: “This will be no mere one-day march in Washington, but a trek to the nation’s capital by suffering and outraged citizens who will go to stay until some definite and positive active is taken to provide jobs and income for the poor.”

Three years earlier, when President Lyndon Johnson declared his war on poverty, 19 percent of Americans—an estimated 35 million—lived below the poverty level. Seeing how poverty cut across race and geography, King called for representatives of American Indian, Mexican-American, Appalachian populations and other supporters to join him on the National Mall in May 1968. He sought a coalition for the Poor People’s Campaign that would “demand federal funding for full employment, a guaranteed annual income, anti-poverty programs, and housing for the poor.”

Assassinated in Memphis on April 4, King never made it to the Mall, but thousands traveled to Washington to honor King’s memory and to pursue his vision. They built “Resurrection City,” made up of 3,000 wooden tents, and camped out there for 42 days, until evicted on June 24, a day after their permit expired.

But the goals of the Campaign were never realized and today, 43 million Americans are estimated to live in poverty. Earlier this year, several pastors started a revival the Poor People’s Campaign with the support of organized labor, focusing on raising the minimum wage.

On the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination and the 50th anniversary of the Campaign, Smithsonian.com spoke with one of the activists who traveled to Resurrection City: Lenneal Henderson, who was then a college student at University of California, Berkeley.

How did you end up at Resurrection City?

In 1967, when I was an undergraduate student at UC Berkeley, MLK came to campus and met with our Afro-American Student Union, of which I was part. He told us about this idea he had of organizing a campaign to focus on poverty and employment generation. One of my professors actually got some money to send 34 of us by Greyhound bus to Washington, D.C., to participate in the campaign.

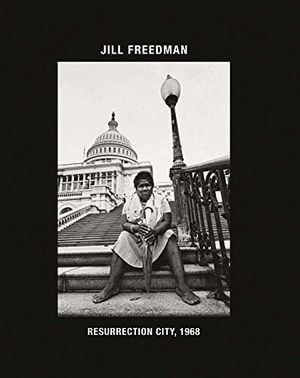

Jill Freedman: Resurrection City, 1968

Published in 1970, Jill Freedman’s "Old News: Resurrection City" documented the culmination of the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, organized by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and carried out under the leadership of Ralph Abernathy in the wake of Dr King’s assassination.

Why did you feel compelled to go?

I was raised in the housing projects of New Orleans and San Francisco, and my parents were very strong community advocates. I also witnessed the Black Panther Party emerge in Oakland in 1966. Stokely Carmichael's call for Black Power focused on the need to transform our communities first in order to get ourselves out of poverty.

What was the journey to D.C. like?

I took a Greyhound bus from San Francisco. But I diverted to New Orleans to see my relatives. I was there when King was assassinated and the very next day, I got back on the Greyhound bus and headed to Washington. From the perimeter of the town, I could see the flames and the smoke of the city going up and the rioting that was taking place. It was pretty sobering. I stayed with a family in D.C. until the Resurrection City was ready to move into.

How did you pass your days in Resurrection City?

Life in the camp was kind of frenzied; it was very, very busy. There were things going on every day, there were people going back and forth, not only organized demonstrations, but to meet with agencies like the Department of Agriculture, Labor and [Housing and Urban Development]. I went to about seven or eight different agency meetings.

I went to some meetings of the D.C. government, and I also went to meetings of D.C.-based organizations that were part of the coalition of the Poor People's Campaign like the United Planning Organization and the Washington branch of The National Urban League. At the camp, we also had something called The University, which was a sort of spontaneous, makeshift higher education clearing house that we put together at the camp for students who were coming from different colleges and universities both, from HBCUs and majority universities.

What was life like inside the camp?

I was there all 42 days, and it rained 29 of them. It got to be a muddy mess after a while. And with such basic accommodations, tensions are inevitable. Sometimes there were fights and conflicts between and among people. But it was an incredible experience, almost indescribable. While we were all in a kind of depressed state about the assassinations of King and RFK, we were trying to keep our spirits up, and keep focused on King’s ideals of humanitarian issues, the elimination of poverty and freedom. It was exciting to be part of something that potentially, at least, could make a difference in the lives of so many people who were in poverty around the country.

What was the most memorable thing you witnessed?

I saw Jesse Jackson, who was then about 26 years old, with these rambunctious, young African-American men, who wanted to exact some vengeance for the assassination of King. Jackson sat them down and said, "This is just not the way, brothers. It's just not the way." The he went further and said, “Look, you've got to pledge to me and to yourself that when you go back to wherever you live, before the year is out you're going to do two things to make a difference in your neighborhood." It was an impressive moment of leadership.

What was it like when the camp was forced to close?

The closing was sort of unceremonious. When the demonstrators’ permit expired on June 23, some [members of the House of] Representatives, mostly white Southerners, called for immediate removal. So the next day, about 1,000 police officers arrived to clear the camp up of its last few residents. Ultimately, they arrested 288 people, including [civil rights leader and minister Ralph] Abernathy.

What did the Poor People's Campaign represent to you?

It represented an effort to bring together poor people from different backgrounds and different experiences, who really had not been brought together before. In fact, they'd been set against one another. People from all kinds of backgrounds, and all over the country came together: Appalachian whites, poor blacks, to mule train from Mississippi, American Indians, labor leaders, farm workers from the West, Quakers. It was just an incredible coalition in the making.

Even though the Economic Bill of Rights we were pressing for was never passed, I think it was successful in many ways. For one, the relationships that those folks built with one another carried on way beyond 1968.

How did the experience impact you?

When I went back to Berkeley to finish my degree, I went back with a certain resolve. And the year after, 1969, I went to work as an intern for California State Senator Mervyn Dymally, who had been also at the Poor People's Campaign. Now, I’m co-teaching a course on the Campaign at the University of Baltimore with a friend of mine. He was also there but we didn't know each other at that time. We kept that resolve going, and kept in touch with the movement ever since.

Resurrection City is also the subject of an exhibition currently on display at NMAH, curated by NMAAHC’s Aaron Bryant. More information available here.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.