Remembering PT-109

A carved walking stick evokes ship commander John F. Kennedy’s dramatic rescue at sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Object-at-Hand-JFK-1943-631.jpg)

John F. Kennedy—elected 50 years ago this month—may not have been the most photographed of America’s presidents, but, like Abraham Lincoln, the camera loved him. His enviable thatch of hair and wide smile, plus his chic wife and two adorable children, turned serious photojournalists into dazzled paparazzi.

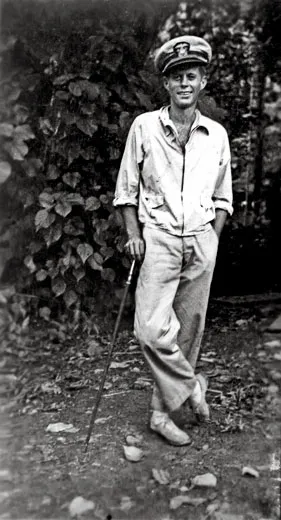

One of the most compelling Kennedy portraits shows him as a young naval officer, leaning on a cane, his smile giving no indication that he was recovering from serious injuries incurred during a near-fatal ordeal at sea. The fellow officer who took that picture, Ted Robinson, recently donated a rare original print of the image—as well as the ironwood cane he lent the future president during his recovery in the Solomon Islands—to the National Museum of American History.

According to the official Navy report, written shortly after the event by Lt. j.g. Byron White (the future Supreme Court justice), 14 PT boats—three-engine wooden vessels armed with two .50-caliber machine guns and torpedoes—left their Rendova Island base at 6:30 p.m. on August 1, 1943, with the mission of intercepting Japanese ships in the Blackett Strait. The group divided into four squadrons, with PT-109 patrolling near Makuti Island.

One of the boat’s men, Ensign George Ross, was on lookout when, around 2:30 a.m., a Japanese destroyer suddenly loomed off the starboard bow, rammed the 109 and cut it in half. Spilled fuel ignited on the water, causing crews of the other PT boats to assume there had been no survivors. Two crew members were never seen again, but 11 who survived, all wearing life vests, managed to board what was left of PT-109. One had been badly burned and couldn’t swim. Lieutenant Kennedy, who had suffered a ruptured spinal disk in the collision, had swum and towed him to the boat.

By dawn, the men abandoned the sinking vessel. Kennedy decided that they should swim to a coral island—100 yards in diameter with six palm trees—three and a half miles away. Again, Kennedy, who had been on the Harvard swim team, towed his crewmate the whole way. The report states undramatically: “At 1400 [2 p.m.] Lt. Kennedy took the badly burned McMahon in tow and set out for land, intending to lead the way and scout the island.”

For the next two nights, Kennedy—sometimes with Ross, sometimes alone—swam from the island into the strait with a waterproof flashlight, hoping to intercept a U.S. torpedo boat. Battling injuries, exhaustion and strong currents, he saw no patrols. On August 5, Kennedy and Ross swam to a neighboring island and found a canoe, a box of Japanese rice crackers and fresh water. They also saw two islanders paddling away in a canoe. When they returned to the island where the crew waited, they discovered that the two natives had landed and were gathering coconuts for the crew. On display at the Kennedy Library in Boston is the coconut shell on which Kennedy scratched a message: “Nauru Isl commander / native knows posit / he can pilot / 11 alive need small boat / Kennedy.”

Kennedy asked the islanders to take the coconut to the base at Rendova. The next day, eight natives appeared on Kennedy’s island with a message from an Australian coast watcher—a lookout posted on another island—to whom they’d shown the coconut. The islanders took Kennedy by canoe to the scout, Reginald Evans, who radioed Rendova. Again, in the measured words of Byron White: “There it was arranged that PT boats would rendezvous with [Kennedy] in Ferguson Passage that evening at 2230 [10:30]. Accordingly, he was taken to the rendezvous point and finally managed to make contact with the PTs at 2315 [11:15]. He climbed aboard the PT and directed it to the rest of the survivors.” The boat Kennedy climbed aboard was PT-157: Ensign Ted Robinson was in the crew.

Robinson, now 91 and living in Sacramento, California, recalls that he and Kennedy were later tentmates in the Solomons. “His feet were still in bad shape,” Robinson says. “So I loaned him a cane I’d received from a village chief and took his picture.”

Not long after, Robinson adds, Marines were trapped during a raid on Japanese-held Choiseul Island. “They landed on the enemy island in the middle of the night,” he says. “Their commanding officer radioed the next morning that he and his men were surrounded and heavily engaged. The CO who received the message said he’d get them out after dark.” According to Robinson, the Marine responded, “If you can’t come before then, don’t bother coming.”

The CO asked for a volunteer to make a daylight dash to save the Marines. “I wasn’t there,” Robinson told me, “but if I’d been, I’d have hidden behind the biggest palm tree I could find.” But Kennedy volunteered. “With a full load of fuel that would get him there and halfway back to where he could be towed home,” Robinson says, “he took off and got the Marines out.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)