The Strike That Brought MLK to Memphis

In his final days, Martin Luther King Jr. stood by striking sanitation workers. We returned to the city to see what has changed—and what hasn’t

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/51/df518896-ac48-443d-978d-b5b00c07dd86/janfeb2018_i01_memphis.jpg)

July in Memphis: You need a way to keep cool. At 10:30 a.m. it’s 88 degrees but feels hotter; by 4 p.m., when the crew is done, it will be 94 degrees. Mike Griffin wears a long-sleeved T-shirt under his fluorescent green vest and, under that, a wet towel around his neck that he recharges periodically with water from a bottle in a cooler. His partner, Mike Holloway, doesn’t believe in the neck towel. He likes a straw hat, and keeps bottles of water in his trouser pockets as he hangs onto the back of the garbage truck.

This route, which the men call Alcy after its main road, is humble single-family homes where most residents are African-American. Small churches are seemingly everywhere: Dixie Heights Congregation, New Harvest Baptist Church, Christ Covenant Church International. Griffin drives fast between stops, and sets the brake and jumps out to help Holloway at most of them—the faster they work, the sooner they’ll be done. The streets are lined with trash cans that people have rolled out for this once-a-week pickup. But at one house, there are no cans; the two men walk up the driveway, disappear behind the house, and reappear dragging plastic bags filled with garbage, and some tied-up yard waste. In Memphis, Griffin explains, senior citizens who register with Solid Waste get special service. (In the old days, he later adds, sanitation workers had to trek behind everybody’s house.)

It smells bad in the front of the truck (I’m mostly in the passenger seat). And it smells bad behind the truck, where Holloway hangs on. Occasionally the breeze might blow it away, but just for a moment. To work on a garbage truck is to spend the day in a miasma of stench.

Every block seems to have piles of old tree branches waiting at the roadside: Memphis suffered through a terrific storm about six weeks earlier. Griffin and Holloway steer around most of the piles; a different crew will collect those. Three times, homeowners approach the men and ask if they can please take the branches. Usually they won’t because the limbs are too large. But they do stop at piles of smaller debris. Each then takes a pitchfork from the side of the truck and uses it to pick up this other stuff, which often stinks in its own way.

I chat with Mike Griffin between stops. He has been on the job nearly 30 years. It’s better than it used to be, he says, but it’s still hard work.

The way it used to be is now legendary: Sanitation workers, treated like casual laborers, who had to show up whether there was work or not, dragged 55-gallon drums or carried open tubs of garbage to the truck. The Number 3 tubs would often leak onto their shoulders; people didn’t use plastic bags in those days. The workers had no uniforms and no place to wash up after work.

“They were the lowest of the lowest in the pecking order,” Fred Davis, a former city council member, told me. “When a kid wanted to put somebody down, they’d refer to their daddy being a sanitation worker.” Workers made about a dollar an hour. Things were so bad in 1968 that, after two workers seeking shelter from rain were accidentally crushed to death inside a truck with a faulty switch, the sanitation workers organized a strike.

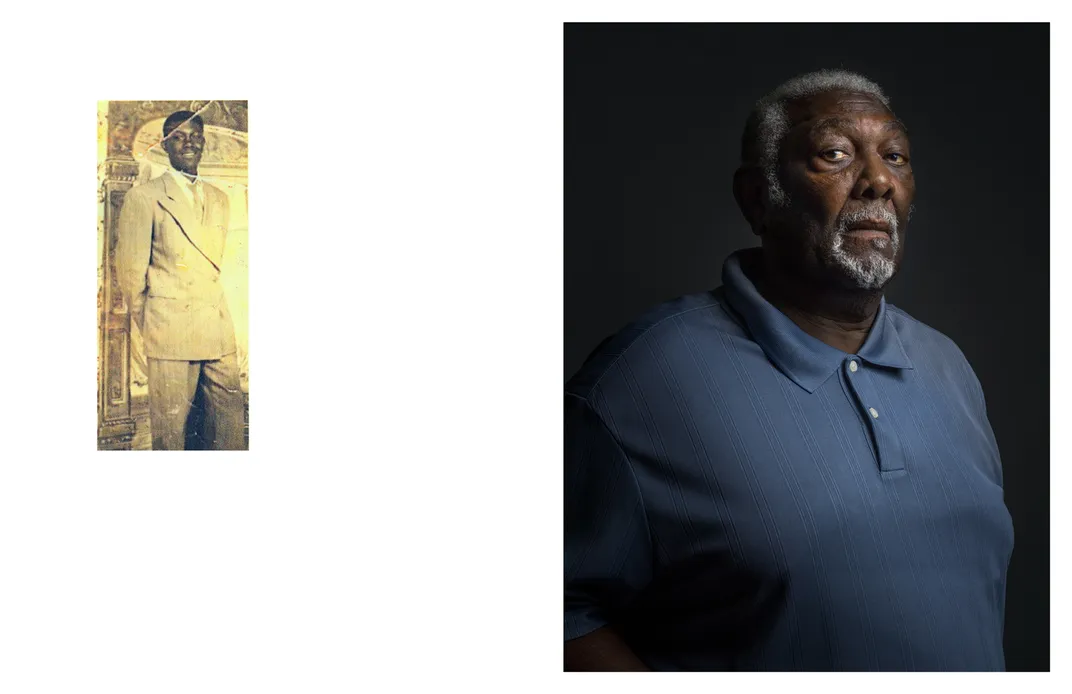

A few of those workers are still alive, and a handful actually still work in sanitation. After the strike, most decided to abandon the city’s pension plan and trust in Social Security; the decision turned out to be a mistake. Still, it was something of a surprise last summer when the city announced it would make cash payments of $50,000, tax-free, to each sanitation worker who had been on the job at the end of 1968 and had retired without a pension. (The city council increased the amount to $70,000.)

Mike Griffin isn’t old enough to benefit but he approves: “I think it’s beautiful. They worked hard and they deserve it.” His brother-in-law, who retired from sanitation last year and is sick, will qualify, he thinks: “It’s gonna help him out a lot.”

I ask Griffin about a doubt I’ve heard others express—whether, after almost 50 years, $70,000 is actually enough. He pauses to think about it. “Well, maybe it should be more,” he answers.

**********

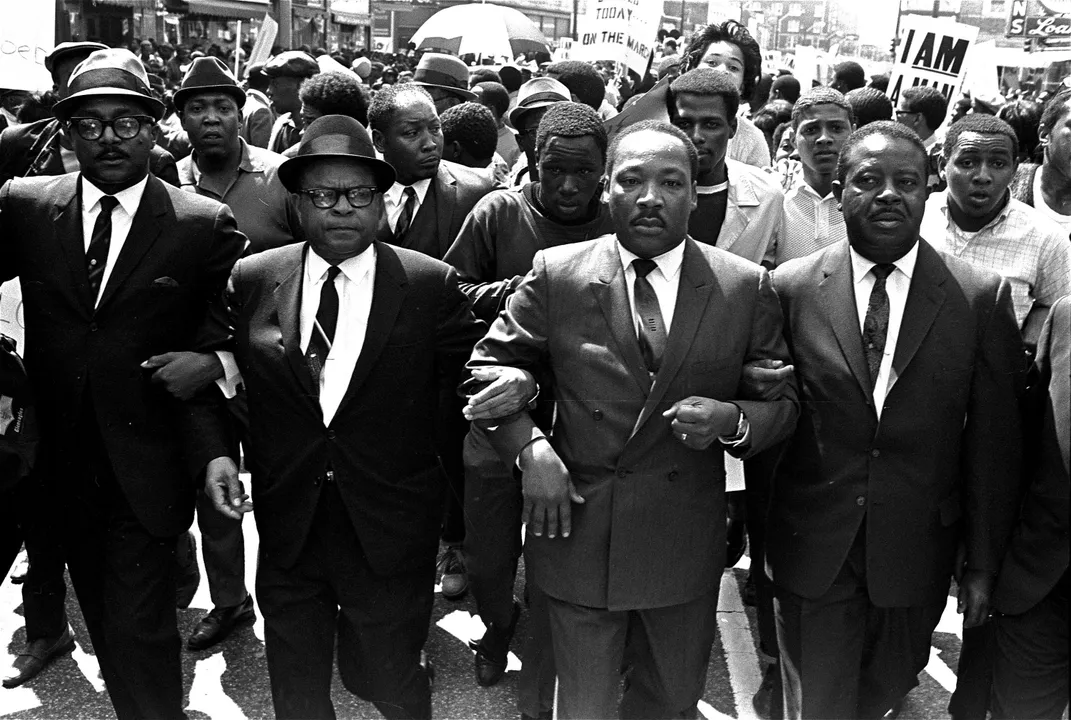

The Memphis sanitation workers’ strike is remembered as an example of powerless African-Americans standing up for themselves. It is also remembered as the prelude to the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

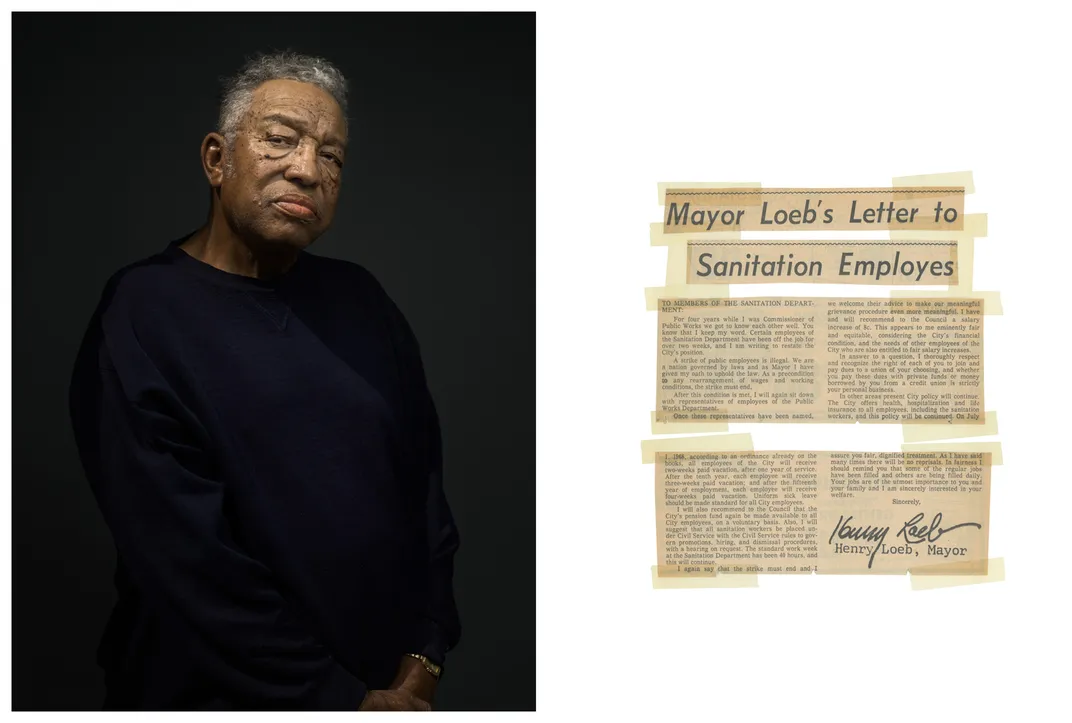

The workers had made a few attempts to strike, several years earlier, but their efforts had failed to attract the support of the clergy or the middle class. By February 1968, though, things had changed. Memphis’ mayor, Henry Loeb, refused to negotiate with worker representatives and rejected a pay raise for workers that the city council had approved. Some of them began holding nonviolent marches; the use of mace and tear gas against demonstrators galvanized support for the strike. One hundred-fifty local ministers, led by the Rev. James Lawson, a friend of King’s, organized to support the workers. King came to town and on March 18 delivered a speech to a crowd of around 15,000 people. He returned ten days later to lead a march. Though King’s hallmark was nonviolent protest, the demonstration turned violent, with stores being looted and the police shooting and killing a 16-year-old. Police followed retreating demonstrators to a landmark church, the Clayborn Temple, entered the sanctuary, released tear gas and, per one authoritative account, “clubbed people as they lay on the floor to get fresh air.”

Some blamed the violence on a local Black Power group called the Invaders. King resolved to work with them and gain their cooperation for another march, to be held April 5. He arrived on April 3 and, as rain poured outside that night, he delivered his famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech to a group of sanitation workers.

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live—a long life; longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. So I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man.”

King and his entourage, including the Revs. Jesse Jackson and Ralph Abernathy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, were staying in a black-owned motel, the Lorraine. As King stood on the balcony outside his second-floor room the next evening, April 4, a white supremacist sniper, James Earl Ray, who had been stalking King for weeks, shot and killed him with a high-powered rifle from the window of a rooming house across the street.

America convulsed; riots broke out across the country. I was 10 years old at the time. A friend of mine who was 20 remembers the assassination as “the day hope died.”

The sanitation strike was eventually settled, with the city agreeing to a higher wage and other changes including recognition of the union, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME).

**********

Memphis had a long decline after King’s assassination. The Lorraine Motel declined as well, and was frequented by drug users and sex workers. In 1982, the owner—who it is said never again rented out King’s room, 306—declared bankruptcy. A “Save the Lorraine” group, financed by the union and the state, bought the motel at the last minute, hoping to turn it into a museum. The plan took nearly ten years; the National Civil Rights Museum opened to the public on September 28, 1991, completing the Lorraine’s transformation from killing floor to brothel to shrine. (The Lorraine’s name was changed from hotel to motel when it was enlarged post-World War II.)

The front of the museum is the motel, with an original illuminated sign and vintage cars parked outside. (Across the street, two other old buildings have become part of the museum, including the rooming house where James Earl Ray stayed.) Behind the motel’s facade, the building was greatly expanded and completely transformed, with a movie theater, bookstore and a sequence of exhibits that take the visitor from slavery to, at the very end, a perfectly preserved Room 306.

Last July, in a meeting room on the museum’s second floor, the city held a special breakfast before the press conference that would announce the payments to the surviving sanitation workers. Present were city employees including Mayor Jim Strickland and the head of the public works department; a few members of the press; one or two representatives of AFSCME; and most of the 14 original workers identified at that point by the city, many accompanied by family members. (The number of workers receiving the payment would eventually grow to 26, and others have applied.)

“Today is to thank and recognize the sanitation workers from 1968, who mean so much to the history of the city of Memphis and to the entire United States of America civil rights movement. We know that we can’t make everything right...but we can take a giant step in that direction,” said Strickland, who had orchestrated the plan, expected to cost nearly $1 million. “Because of the risks you took, the city of Memphis today is better than it was.”

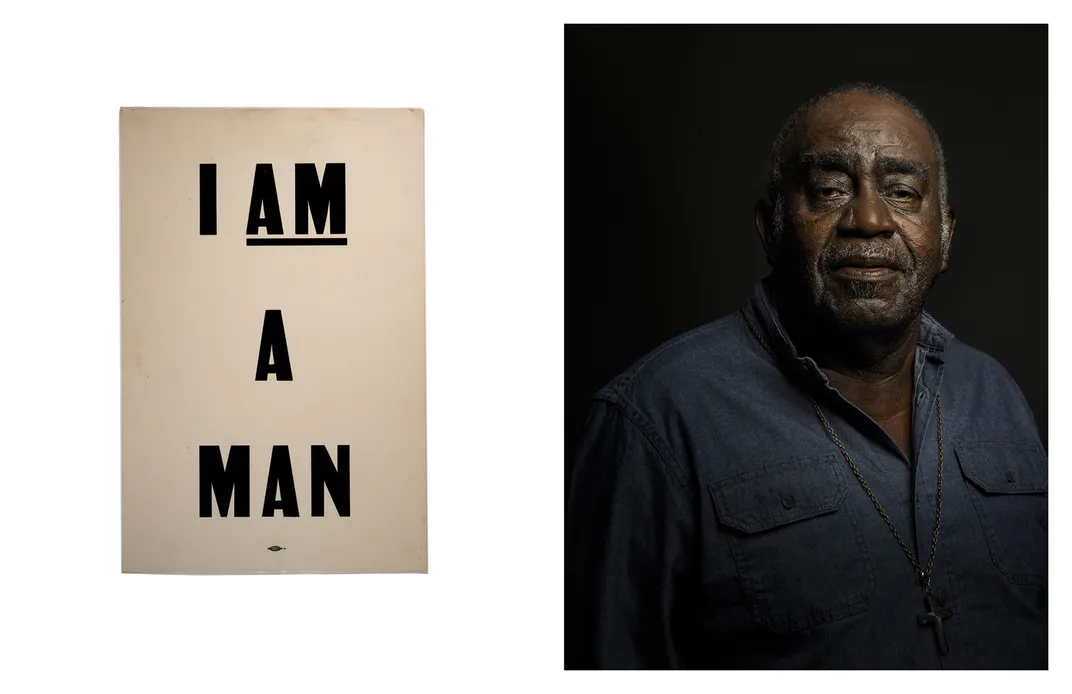

His public works director, Robert Knecht, praised them as well, “not only for enduring so many hardships and trials during the 1968 strike, but for your courage and willingness to stand tall and say yes, I am a man, to say we deserve to be treated equally and receive fair wages for our work, to be afforded the opportunity to organize.” Four of the original workers, he noted, were still city employees, including Elmore Nickelberry, 85, who had been hired in 1954. He gestured at Nickelberry, who was seated at a table wearing a coat and tie, and recounted how he called him to ask if he could attend the breakfast. Nickelberry’s reply: “OK, but I don’t want to be late for work.”

**********

How many city officials, in America or the world, have ever offered such encomiums to municipal workers who went on strike—in this case, for more than two months?

The historian Michael K. Honey, author of Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign, told me that over the years, Memphians went from shock and shame over their town’s being the place of King’s murder to commemorating it as part of the legacy of the civil rights movement. “When I lived there in ’76, the city wanted to tear down the Lorraine Hotel—they wanted to forget this ever happened,” he said. “Supporting the effort to convert it to a museum is one of the best things Memphis ever did.”

Without question, civil rights tourism matters to Memphis. The museum these days almost always has a line of people waiting to get in, many or most of them African-American. An entire room, complete with an actual, old-style garbage truck of the kind that killed the two workers in 1968, is devoted to the sanitation workers’ strike. Others are dedicated to the Montgomery bus strike (there’s a bus), discrimination at Woolworth’s (there’s a lunch counter), the desegregation of the University of Mississippi, King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and more. The commemoration of civil rights in Memphis is of a piece with tourist attractions that celebrate black music and culture, such as Stax Records, barbecue restaurants (Rendezvous Ribs is perhaps the most famous, but everyone in Memphis has their favorite), and the honky-tonk night scene on historic Beale Street.

Sometime after the press conference, I asked the mayor in his office: Why did the city come up with these payments when nobody was demanding them?

He said it was just a question of doing the right thing. After all these years, sanitation workers were still being disadvantaged by their decision to leave the city pension system in 1968; they had gotten bad advice. The cash payments piece was the brainchild of L. LaSimba Gray Jr., pastor of New Sardis Baptist Church, one of his advisers. “We also knew that the 50th anniversary of the strike and assassination was coming up,” and felt the timing would be right for some kind of gesture.

Would it be right to call the grants reparations, I asked? The term is part of a national conversation about compensating the descendants of slaves. Strickland (who is Memphis’ first white mayor in 24 years) replied that the word had never come up, and that he didn’t think so. “It’s certainly not reparations for slavery, [and] though I’m not an expert, the argument has always been based on slavery. I don’t think you could even say it’s reparations for abuse or Jim Crow laws or anything [like that].”

But Memphis is a majority-black city with deep divisions on matters of race, and plenty feel there’s an argument for reparations based on abuse that falls short of slavery. King himself toward the end of his life had begun to focus on economic justice; in speeches across the Bible Belt earlier in 1968 that promoted his Poor People’s Campaign, he noted that most freed slaves had never received their “40 acres and a mule,” and said that the nation had left blacks “penniless and illiterate after 244 years of slavery.” Calculating that $20 a week for the four million slaves would have added up to $800 billion, he concluded, “They owe us a lot of money.”

A local journalist, Wendi C. Thomas, wrote that if the city had instead given the workers $1,000 a year from 1968 to the present, with 5 percent compound interest it would today be worth $231,282.80.

Various activist groups in Memphis even now trace their concerns to those of King and of the sanitation workers. There are many, including the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center, the Memphis Coalition of Concerned Citizens, One Memphis One Vision, the Fight for $15 campaign (for a higher minimum wage), a drive to organize university workers, and two competing Black Lives Matters groups. Members of all of them, and many other people besides, came together dramatically on July 10, 2016. They were angry over recent police shootings such as those of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Philando Castile in Minnesota, and a local man named Darrius Stewart. A group of some 200 marchers, led by an activist named Frank Gottie, were walking from the National Civil Rights Museum toward the Criminal Justice Center downtown when they crossed paths with Michael Rallings, the recently named interim director of the Memphis Police Department, near the FedExForum arena. Rallings, who had been en route to an interview at WLOK-AM, a venerable gospel music radio station, stopped to speak with them.

Rallings, who today is the police chief, told me that Gottie “had a megaphone and asked me if I wanted to say anything. I said I recognize this is your protest, I just want everybody to be peaceful.” When they turned away from the Criminal Justice Center and toward the bridge that carries Interstate 40 across the Mississippi River to Arkansas, Rallings sped there in his car.

They had blocked traffic by the time he arrived, and he waded into the crowd with two other officers, also African- American. Rallings told me that he associates the bridge with “jumpers” who are sometimes successful in killing themselves by plunging into the Mississippi, and was worried that if pushing or shoving erupted, people could fall.

Rallings walked through the crowd, often getting yelled at but trying to start a conversation.

I Am a Man!: Race, Manhood, and the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was first and foremost a struggle for racial equality, but questions of gender lay deeply embedded within this struggle. Steve Estes explores key groups, leaders, and events in the movement to understand how activists used race and manhood to articulate their visions of what American society should be.

“I just kept thinking about King and Selma, Alabama, and how a negative incident [here in Memphis] could have made Selma look small.” (Civil rights demonstrators heading to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in south Selma, were attacked by police in 1965, with scores injured.) Rallings, who was born in 1966 and grew up in Memphis, said, “Being an African-American male, my parents and grandparents obviously shared stories of everything that surrounded the civil rights movement, so I was very familiar with the possibilities of how bad things could actually become. I didn’t want that to happen ever again in my city, and definitely not on my watch.”

To the demonstrators who wanted a dialogue, Rallings said, “We can’t talk on the bridge, we gonna have to get off the bridge....We ended up leading the march. Me and some other officers ended up in locked arms with several, and we walked off the bridge. A lot of folks in front of us, they saw the movement and moved in front of us. On the way down they discussed having a follow-up meeting. The time and location was all negotiated as we walked on the bridge. That was almost a two-mile walk, and we were all tired, and so my officers brought water to the protesters. We just wanted a peaceful resolution to a tense situation.”

Up to 2,000 people took part in the protest, according to the police—the biggest demonstration in Memphis since the sanitation workers struck in 1968.

**********

Could a line be drawn from Selma in 1965 and the sanitation workers’ strike in 1968 to the activism of today? Shahida Jones, an organizer of Black Lives Matter in Memphis, was quite sure it could. The fight is still for black liberation, she said—“all the ways we’re marginalized and all the ways we’re trying to get free.” Specifically, the group is focused on abolishing money bail, on what she called transformative justice in the school system (“ways [to] address performance and behavioral issues in school systems that don’t result in suspension or jail”), and on the decriminalization of marijuana. Memphis has too many low-paying jobs with few or no benefits, she said. It is still a city with widespread black poverty; those with money, racially speaking, have hardly changed at all. True, today’s solid waste workers make $17 to $19 an hour, a big improvement. But the city’s marked income inequality—the particular concern of King at the end of his life, the problem that brought him to Memphis—remains strikingly intact.

Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge was named for a Confederate general who had also been a Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. A monument near downtown Memphis featured a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, also a Confederate general who had been the Grand Wizard, or national chair, of the Ku Klux Klan—and a slave trader, to boot. (It was removed by the City of Memphis in December.)

One morning last fall Charlie Newman, a lawyer and longtime civic figure who has played a role in numerous good causes over the years, drove by the monument on his way to work. He reported to me that three police cruisers were stationed there, evidently to dissuade anyone who might want to do the statue harm. Though Newman is best known for his work on projects that preserved green space and created trails around the city, before then he played a role in a national civil rights drama with Memphis at the center.

After violence broke out during King’s first march to support striking sanitation workers, on March 18, he planned a second one for April 4, 1968. But the city got a federal court to issue an injunction against it. King needed help lifting the injunction and the law firm Burch Porter & Johnson, where Newman worked, offered its services. A well-known photograph shows five men heading to court on April 4: King advisers James Lawson and Andrew Young, the firm’s Lucius Burch, Charlie Newman and their partner, Mike Cody.

Over lunch at the Little Tea Shop, an unprepossessing restaurant a few blocks from his law offices, Newman talked about the incident. He had gone to the Lorraine Motel to speak to King on April 3, the day before the court date, said Newman, and had sat on the edge of the same bed visitors now look at behind glass at the National Civil Rights Museum. “I’d seen him once before, in college. He had an almost visible aura about him, an energy I’ve never seen before or since. He was one of the few indispensable men or women. If we hadn’t had him, I’m not sure we would have made it through that period.”

That night, King delivered his last speech. In court the next day, Newman and company prevailed—the city would have to allow the march. But the victory was short-lived. As the team was walking back from court to the office, Newman heard sirens, he said, and then the news: King had been shot.

Newman graduated from Memphis High School before heading to Yale for both his bachelor’s and law degrees, but he was born in Mississippi. Such is life in these parts that the middle name of this progressive activist is Forrest, after the Confederate general. Charles Forrest Newman. “My great-grandfather was in the Battle of Antietam at 19 to 20 years old, and he named his first child, my grandfather, Charles Forrest—Forrest’s reputation was in its ascendancy. So my parents named me for my grandfather.”

Memphis today is 64 percent African-American. Pressured by a group led by activist Tami Sawyer, the city council last August expressed its support for removal of the Nathan Bedford Forrest statue, as well as one of Jefferson Davis in a different park. But they were thwarted by Tennessee Historical Commission, a state group that must approve any changes to public monuments. Then, in December 2017, the City claimed victory: it transferred ownership of the parks where the monuments were located to a nonprofit entity, said this allowed them to get rid of the statues, and promptly did.

Charlie Newman was not upset.

"Memphis is still struggling with the consequences of hundreds of years of slavery and de facto slavery," he told me. "Forrest was a military genius of a sort, but before that he was a slave trader of the worst sort, who made a fortune buying and selling human beings. He then used that genius to defend slavery.”

"The descendants of people he bought and sold shouldn’t have to explain to their children why he’s still being honored with the most prominent statue in town."

**********

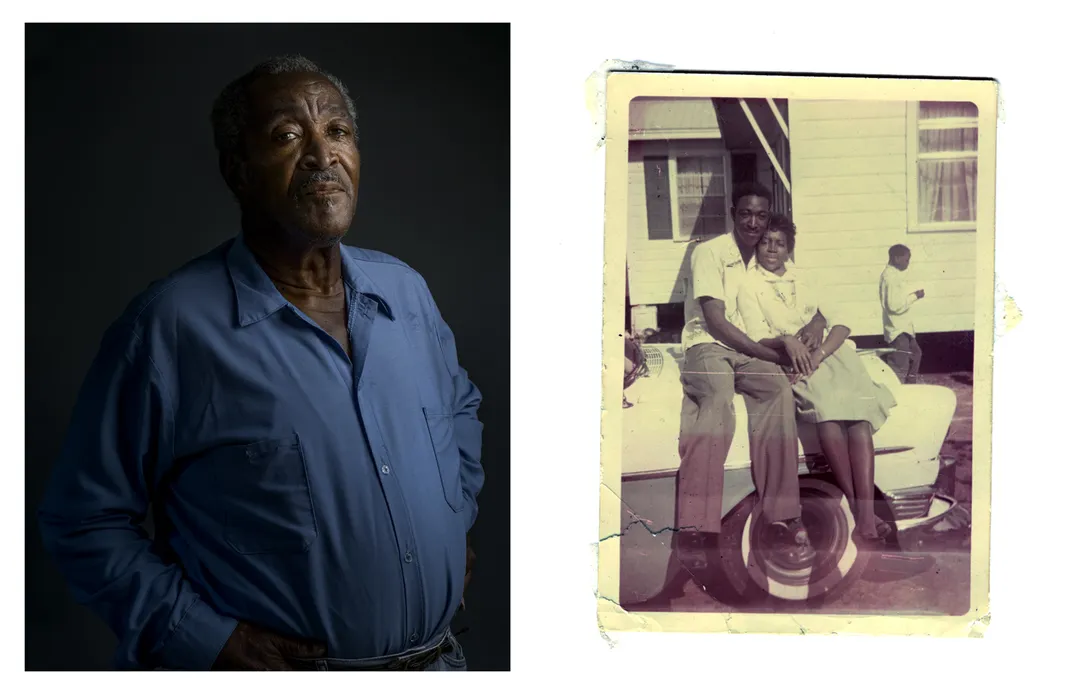

Across town, the lunch crowd had packed the Miss Girlee Soul Food Restaurant, owned and run by the family of retired sanitation worker Baxter Leach. I’d met Leach at the mayor’s announcement breakfast, and he has often been the public face of the surviving striking workers. He spoke at the national Teamsters meeting in Las Vegas in 2016, and in 2013 addressed fast-food workers in New York City who were considering joining a union. On the wall at Miss Girlee are photos of him and other workers with President Obama in 2011, and with Stevie Wonder; he once spent a week with Jesse Jackson and his Rainbow Coalition. Behind the counter stood his wife and his oldest son; his vivacious granddaughter, Ebony, brought us plates of chicken, greens and corn bread. I asked Leach, who was at the next table with others, if he supervises the employees.

“I don’t do nothin’!” he said. “I talk with my friends.”

Later he spoke about how it used to be. The trucks had crews of four or five; the only white employees were drivers, who didn’t have to do the hard work of fetching buckets of garbage from behind people’s houses. One of his crewmates had lost a leg when a car crashed into the back of the truck. Another lost two toes in a different incident. After a shift, white workers were the only ones allowed to shower at the depot; everybody else had to ride the bus home stinking.

As for the strike, it had been a huge trauma. After violence broke out, some 4,000 National Guardsmen had flooded the city. They lined the streets at subsequent marches, their rifles fitted with bayonets pointed at demonstrators. Scabs had been brought in to pick up trash; some of the strikers fought with them. The strikers knew there were spies among them, reporting to the police and the FBI; they also knew that not all the workers were supporting the marches. (Leach, Alvin Turner and others I spoke to assert that not all the old-timers singled out for recognition recently had actually joined the strike.) But Leach said he never regretted the strike for a second: “Things was just so bad. Something had to change.”

**********

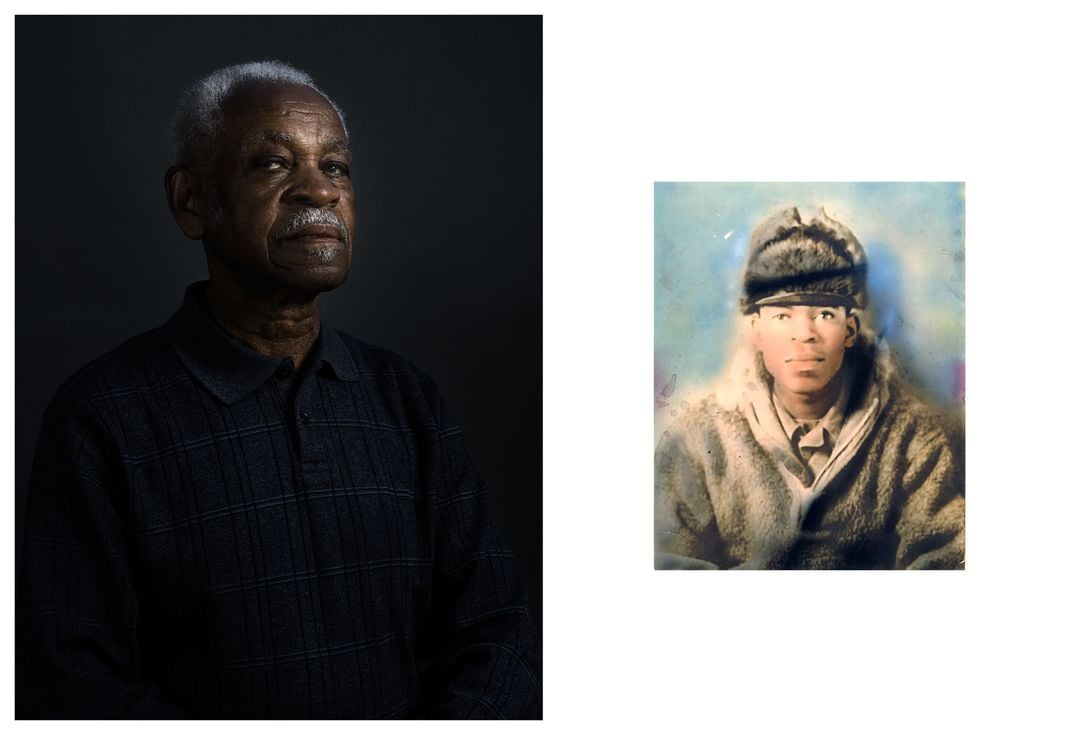

A month or so after that day in his restaurant, Leach called his old friend James Riley, 75, in Chicago. Leach urged him to drive down from Chicago to join a photo shoot for this article. Riley, 75, is pictured in a gathering of strikers holding signs with the famous slogan from the strike, “I Am a Man.” The iconic photo is on display in the National Civil Rights Museum. Riley’s proud of that image and so is Christopher, his son, who is in the clothing business: He had T-shirts made with the image emblazoned on the front. James and Christopher Riley arrived to have their photos taken at the Memphis AFSCME hall.

Like Leach and many other sanitation workers from the time, Riley grew up in Mississippi, the son of sharecroppers. There he made about $3 for ten hours of work; sanitation in Memphis paid $1 to $1.35 per hour and so, at age 23, he moved north. But he grew disillusioned with the job. “Most of them tubs leaked like hell. They had an odor, and when it started leaking, and you put that tub on your shoulder and put it on you it would leak on you and you’d smell like garbage.”

The year after the strike, he quit and again moved north...and so he was not included in the city’s payments to the original strikers.

But H.B. Crockett, 76, was. The Memphis resident retired only three years ago. He too emigrated from Mississippi and left home at age 18. That wasn’t old enough to work for the city, so “I had to put my age up, to 21—I got away with it.”

One of Crockett’s most vivid memories of the strike is the night he heard Martin Luther King’s last speech. “Everybody listened to him—white and black listened to him. I believe it was more black than white that night. It was just packed. He said, I have a dream, I have a dream, I been to the mountaintop, he allowed me to go up there, and I seen the promised land. [When union organizers passed the hat that night,] they took up so much money, they filled ten garbage cans full of money.”

I had hoped to visit another former striker at home in Memphis, but his daughter, Beverly Moore, explained that Alvin Turner, 82, was too sick with cancer to see anybody. She asked me to call instead. He had trouble speaking, and so Moore took the phone and translated. Though her father had worked in sanitation for 25 years, she said, the city had informed him that he wasn’t going to be eligible for the payment, because he was one of the few that had stuck with the old pension plan. Though he was disappointed, she said he wasn’t as bad off as many.

“I tell people all the time my daddy was a garbage man, but he had a businessman’s mentality.” Turner had started some businesses on the side, and made money. Two of Moore’s sisters received PhDs (one was a vice president of Spelman College), and her brother was a successful real estate investor. She herself had recently retired from the U.S. Navy, as a petty officer first class.

She said her father’s proudest moment was when he and some other original strikers visited President Obama at the White House, “and he said he might not have been president had they not taken their stand.”

I called Turner and Moore again a few weeks later to check in, but I was too late: Alvin Turner passed away last September 18, at age 83.

**********

For my Memphis visit, I rented a house on Mulberry Street through Airbnb. Mulberry Street is short, and the house was just a block from the National Civil Rights Museum. When I stepped out the front door, I could see the neon Lorraine sign on the corner of the building. I wanted to get as close to the history as I could, and that seemed like one way. Talking to Charlie Newman seemed like another. When I met Henry Nelson, I found a third.

Nelson, 63, had a long career in Memphis radio. He had been on-air at WLYX, a progressive rock station, on the campus of Southwestern at Memphis (now Rhodes College) and for WMC’s FM-100 (“the best mix of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s”), and he helped start WHRK-97, a hip-hop and R&B station. But when I met him in his large office at the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library, where he is a community outreach and projects specialist for the public library system, he said his main job in life had always been connecting people, finding what they had in common.

Nelson, whose graying hair falls over his shoulder in dreadlocks, is handsome and animated. His office computer was softly playing Tibetan chants.

We talked about his growing up in Memphis. “I come from a family of help,” he said. “My mom was a maid.” His brother Ed was for a while an activist who joined the local Black Power group, the Invaders. “I’m the good son, he’s a son of the streets,” said Nelson. He talked about his history in radio, about the central importance of blues music and Stax Records and Art Gilliam’s WLOK-AM radio near the Lorraine, “the station that was right in the courtyard of the assassination...that became the voice of widening the community.” Stax, he said, “closed down in the early ’70s because of King, because of what happened in the city.” Not long after, “the downtown area was hollowed out...and really it’s still that way.” Memphis post-assassination “became a place of diminished esteem...for people whose esteem was already suffering. Victimization, poverty, lack of hope...it all got worse.”

Nelson is also a writer, and in April he published an essay in Memphis Magazine about his older sister, Mary Ellen. She worked at the Lorraine Motel and was there the day King was shot and killed. In fact, she appears in a famous photo. On the second-floor balcony, next to the fallen civil rights leader, several members of King’s entourage point at the rooming house where the shot came from; below, on ground level, amid other employees, the motel’s owners, Walter and Loree Catherine Bailey, and police, a woman holds her hand over her mouth. It is Mary Ellen. In addition to working on the motel switchboard and in its kitchen, she cleaned rooms. In fact, she told her brother, the housekeeping cart outside King’s room in the photo was hers.

Mary Ellen soon relocated to Lansing, Michigan, where she lives today, a retired school bus driver and mother of four. Nelson notes that she never liked talking about what happened.

Raka Nandi, collections manager and registrar at the National Civil Rights Museum, commented to Nelson that while “many people want to insert their story into the lives of historical figures or celebrities...Mary Ellen did not want to cheapen her memory of this moment by being perceived in this way.” Though Nelson thought Mary Ellen was finally ready to speak about that day and gave me her number, the half-dozen texts and voicemails I left went unanswered.

**********

Elmore Nickelberry, 85, is referred to without exception in Memphis as “Mr. Nickelberry.” As one of the last sanitation workers who experienced the strike, he is the city’s go-to man when somebody like me asks to interview an original worker. My turn came one evening last July. Terence Nickelberry, his son, oversees the north solid waste depot, and we sat in his office while we waited for his father to get his truck. About his workers, Terence said, “If you haven’t got sprayed with urine [shot out from a bottle under pressure], smacked with a limb or smeared with feces, you haven’t been doing your job.”

His father, when I met him, was a dignified, lean man who shook my hand and introduced me to his work partner, Sean Hayes, 45—who also called him Mr. Nickelberry. The three of us climbed into the front of Nickelberry’s truck and headed toward downtown. I was surprised by the cool air emanating from the dashboard. “You have AC?” I asked.

“For some reason it’s working,” replied Nickelberry wryly. The truck started picking up garbage nearby Sun Studio, on Union Avenue—where Elvis was discovered. Like Mike Griffin’s rig, it had hydraulic lifts on the back that raised the city-supplied garbage bins and tipped them into the hopper at the rear. Sometimes Nickelberry waited in the cab while Hayes brought the bins to the truck, tipped them in, then returned them to the curb, but often he got out to help. We headed down Monroe then crossed over Danny Thomas Boulevard, toward AutoZone Park stadium, where the Memphis Redbirds play baseball, and the tall buildings of downtown. We stopped outside a fire station; Hayes and Nickelberry went in for a while to chat with the guys. I was getting the feeling this might not be the hardest route in Memphis Solid Waste.

Nickelberry stayed chatty when he got back in the truck. Like Griffin, he wanted to tell me about the bad stuff that sometimes happened when the bins got tipped into the truck and then compressed. Bottles of paint thinner would explode and spray. Kitty litter that wasn’t tied up in a plastic bag would cover the workers with foul dust, causing them to break out in hives. “You never know what’s inside those cans until you dump ’em,” he said. We headed south, toward the civil rights museum, and when we were near I asked Nickelberry where Clayborn Temple was— I had yet to pay a visit. “I’ll show you on the way back,” he said. An hour later, he diverged from his route, traveled across a few blocks where buildings had been razed and not yet replaced, and then parked the garbage truck across from a beautiful big church. He put the truck in park, climbed down, and told me to follow.

“I want you to take pictures of that,” said Nickelberry, indicating the main door of the Romanesque Revival building. (I’d been shooting photos with my camera as we went.) “We ran in there when the police chased us” during the march. “And take a picture of that”—he pointed at a window that had been broken, he thought, when the police shot tear gas into the sanctuary, flushing everybody out. “The police hit me on the arm and ran me down to the river,” he said.

We took a short walk to the vacant lot across the street, which I knew the city plans to turn into the I Am a Man memorial park. (Recently the city added posters to the side of garbage trucks that read, I AM MEMPHIS.) Nickelberry hadn’t heard about the park, but he liked the idea. He also approved of the way Clayborn Temple was being renovated. Originally a segregated Presbyterian church, it belonged to the A.M.E. Church (which named the building after its bishop) by 1968. The protest march led by King had started from there on March 28, as had numerous marches earlier in the strike.

It was late when we headed back to the depot. Nickelberry told me that once he received his payment from the city, he actually might retire. That’s when it occurred to me that the reason he was still working was possibly that without a pension, he had to. I asked him, but he didn’t want to comment. Was the $70,000 from the city enough, I asked?

“I don’t think it’s enough,” said Mr. Nickelberry. “But anything’s better than nothing.”

(Additional reporting by Aaron Coleman)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.