Revolutionary Real Estate

Statesmen, soldiers and spies who made America and the way they lived

America's founding fathers shaped one of history's most dramatic stories, transforming 13 obscure colonies into an emerging nation whose political principles would change the world. But to see them in the household settings they shared with wives and families and in the intimate context of their very different era, is to understand the founders as individuals, extraordinary ones, to be sure, but also men who supped and shaved, wore slippers and read by candlelight. It was also an extraordinary time, but a time of achingly slow communications and travel, primitive and perverse medical care, a moral code that had only begun to condemn slavery, and ways of living that seem today an odd mixture of the charming, the crude and the peculiar.

The founders shared a remarkably small and interconnected world, one that extended to their personal as well as their public lives. When New Jersey delegate William Livingston rode to Philadelphia for the first Continental Congress, for instance, he traveled with his new son-in-law, John Jay, who would be the first chief justice of the United States Supreme Court. The president of that Congress was Peyton Randolph, a cousin of

Thomas Jefferson and mentor of George Washington; another Virginia delegate, George Wythe, had been Jefferson's "faithful Mentor in youth." John Adams and Jefferson first met at the second Philadelphia Congress in 1775; half a century later, after both had lived long and colorful lives, they were still writing to each other.

Of course the name that seems to connect them all is Washington, the era's essential figure. His adjutants included painter (and sometime colonel) John Trumbull; the Marquis de Lafayette, whom he regarded almost as an adopted son; future president James Monroe; and his chief of staff, the precociously brilliant Alexander Hamilton. Among his generals were Philip Schuyler of New York and Henry Knox of Massachusetts. Years later, Washington's first cabinet would include Secretary of War Knox, Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton (by then married to Philip Schuyler's daughter Betsy), Secretary of State Jefferson and Attorney General Edmund Randolph, another Jefferson cousin. Washington appointed Jay to the highest court, and John Adams served as his vice president. It was a world characterized by enduring ties of blood, marriage and political kinship. And imposing, classic architecture.

These pages showcase a variety of historic 18th-century houses. (Neither Washington's Mount Vernon nor Jefferson's Monticello, the best known and most visited of the founder's houses, are included in this excerpt, though they are part of the new book from which it comes, Houses of the Founding Fathers; each deserves an article of its own.) Some were occupied by such important personages as John and Abigail Adams. Others memorialize lesser-known figures, such as America's first spy, Silas Deane of Connecticut, and pamphleteer and delegate to the Continental Congress William Henry Drayton. All the houses are open to the public.

Drayton Hall

Charleston, South Carolina

As a delegate to the Continental Congress, William Henry Drayton of South Carolina took part in a number of acrimonious debates over such important issues as military pensions, British proposals for peace and the Articles of Confederation. Drayton was also outspoken about a suitable way to mark the third anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Thanks to his advocacy, "a very elegant dinner" followed by a "brilliant exhibition" of fireworks won out—the origin of our Fourth of July celebrations.

Once the center of a busy 660-acre plantation—with stables, slave quarters, a poultry house, lime kiln and privy—Drayton's childhood home now stands alone. But it remains the house he knew, largely untouched and authentic—and all the grander for it.

William Drayton never became master of Drayton Hall. His father disinherited him when William stayed in Philadelphia to serve in the Continental Congress rather than coming home to defend South Carolina when British troops invaded in 1779.

The Deshler-Morris House

Germantown, Pennsylvania

"We are all well at present, but the city is very sickly and numbers [are] dying daily," President George Washington wrote on August 25, 1793. As he put it, a "malignant fever" (actually yellow fever) was racing through Philadelphia, the young nation's capital.

A reluctant Washington sought refuge at his Mount Vernon plantation in Virginia, but by the end of October reports from Philadelphia suggested that new cases of the fever were diminishing. In November, the president returned to Pennsylvania, establishing a temporary seat for the executive branch in the village of Germantown, six miles north of the capital. He rented a house from Isaac Franks, a former colonel in the Continental Army who had bought the home after the original owner, David Deshler, died. By December 1, Washington was back in Philadelphia, but he returned to the house—the earliest surviving presidential residence—the following summer.

The Silas Deane and Joseph Webb House

Wethersfield, Connecticut

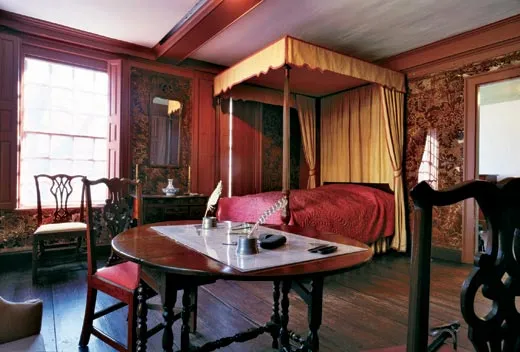

The two houses sit side by side in the port town of Wethersfield, overlooking a bend in the Connecticut River. Their tranquil setting belies an intriguing past.

Educated at Yale, Silas Deane opened a law office in Wethersfield in 1762. He served in the Continental Congress in 1774 and 1775, and was appointed by Benjamin Franklin and Congress' Committee on Secret Correspondence to travel to France in 1776 "to transact such Business, commercial and political, as we have committed to his care." He was to pose as a merchant, but covertly solicit money and military assistance from France. Deane arranged for the export of eight shiploads of military supplies to America and commissioned the Marquis de Lafayette a major general. But Deane was later accused, falsely it seems, of misusing funds and spent a decade in exile in Europe. He died mysteriously in 1789 on board a ship headed home.

The house next door to "Brother Deane's" also had Revolutionary connections. Samuel B. Webb, son of its builder, fought at the battles of Bunker Hill and Trenton and became an aide-de-camp to General Washington, who by happenstance would spend time at the Webb House in the spring of 1781, meeting with French military officers to plan the final phase of the Revolutionary War.

John Adams' "Old House"

Quincy, Massachusetts

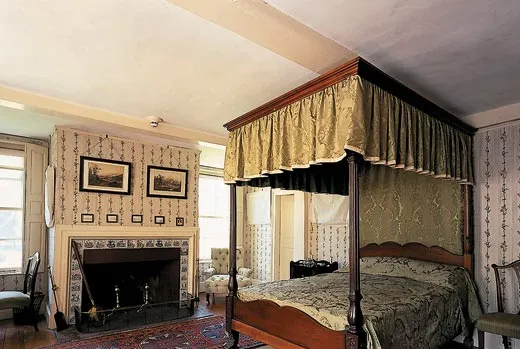

John and Abigail Adams bought the home they would call "Old House" in September 1787 while still in England, where John was serving as minister to the Court of Saint James's. When they moved into the house the following spring, they found it confining. To Abigail it resembled a "wren's nest" with all the comfort of a "barracks." The couple added a kitchen ell and inserted two windows to overlook the garden, but just as they settled in, John was elected vice president. He served eight years (1789-1797) in that office and four more as president (1797-1801). Before returning to Massachusetts, the Adamses enlarged Old House, almost doubling its size.

Adams died at age 90, on July 4, 1826—within hours of Thomas Jefferson and 50 years to the day after signing the Declaration of Independence—confident that the experiment the founding fathers had launched would succeed.

George Mason's Gunston Hall

Mason's Neck, Virginia

If you drive the bear from his lair, don't expect him to be happy.

No longer young, George Mason found himself in Richmond, engaged in a pitched parliamentary battle of the sort he despised. Before the Revolution, he had withdrawn from elective politics, nervous about his health and impatient with other men's inflated oratory. Yet like so many of his generation, George Mason (1725–1792) had come back into public life to fight for his ideals and interests.

In the autumn of 1788, he was taking part in one final debate about the shape of the new American government. The Virginia Assembly had convened to ratify the Constitution, which Mason had helped draft the previous year in Philadelphia. But the irascible old militia colonel was there to oppose it, and his harsh arguments disappointed his colleagues. Unwilling to compromise, Mason found himself witnessing the ratification of the Constitution, which lacked what he thought were essential changes regarding individual rights and the balance of powers.

The embittered Mason retreated to his plantation on Dogue's Neck. Eventually, his personal promontory would be renamed Mason's Neck in honor of the old Patriot. But in his lifetime, his determined opposition to the Constitution cost Mason dearly.

From his formal garden, Mason's vista reached to the Potomac, a quarter mile away. He could watch ships departing from his own wharf, carrying his cash crop, tobacco, off to market. He himself had often embarked there on the short journey upstream to dine with George Washington at Mount Vernon. The men had a friendship of long standing. Though Mason had not been trained as a lawyer, Washington had called upon his renowned legal expertise in untangling property disputes, as well as for the revolutionary thinking that would prove to be Mason's most important legacy. The two men served as members of the Truro Parish Vestry, overseeing construction of the Pohick church, where their families worshipped together. In a 1776 letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, Washington summed up their relationship, calling Mason "a particular friend of mine."

Yet what Washington had termed their "unreserved friendship" came to an abrupt end after the events of 1788. The two had had other differences over the years, but the thin-skinned Washington broke off the friendship when Mason opposed ratification. After becoming president a few months later, Washington delegated one of his secretaries to respond to Mason's letters. More pointedly, he referred to Mason in a note to Alexander Hamilton in imperfect Latin as his "quandam [former] friend."

Alexander Hamilton's The Grange

New York, New York

As he sat at his desk writing, Alexander Hamilton could hardly help but think of his eldest son, Philip, namesake of his wife's father, General Philip Schuyler. Two years earlier, the nineteen-year-old boy had died in a duel—and now here his father was, putting pen to paper under the heading "Statement of the Impending Duel." Hamilton was readying for his own confrontation at dawn the following morning.

He expected an outcome quite different from what had befallen his son. Throughout his life, Hamilton had overcome great odds to succeed where other men might have failed. Not that he anticipated the fall of his challenger, the sitting vice president, Aaron Burr; in fact, as he wrote, "I have resolved . . . to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire." Hamilton was forty-nine years old, and after years immersed in political controversies, he was out of government service. His old mentor George Washington was five years buried. His chief political nemesis, Thomas Jefferson, was ensconced in the President's House. And the Federalist party that Hamilton had helped establish seemed to be marching inexorably into irrelevance.

Hamilton reviled Burr and what he stood for. Or rather what he did not stand for, as Hamilton had been heard to observe that Burr was "unprincipled, both as a public and private man." It was a matter of honor for him to stand up to Burr, although viewed from a more modern perspective, it was a fool's errand, since Hamilton had nothing whatever to prove. His life had been filled with accomplishments. After success as General Washington's adjutant, he had won admiration for his bravery at the Battle of Yorktown. In civilian life he had served in the congress under the Articles of Confederation, then cowritten with James Madison and John Jay the essays in The Federalist, which were instrumental in winning ratification of the Constitution. As the first secretary of the treasury (1789–1795), he created a plan for a national economy, established a national bank, devised a means of funding the national debt, and secured credit for the government. Many people disliked Hamilton—his politics favored the rich, and he himself was vain and imperious, never suffered fools gladly, and had a dangerously sharp tongue—but no one questioned his intelligence or his commitment to the American cause.

But Hamilton wasn't writing about what he had done. His mind was on the impending duel and what he had to lose. "My wife and Children are extremely dear to me," he wrote, "and my life is of the utmost importance to them, in various views."

Hamilton's recent fade from public life had had two happy consequences. Now that he had time to devote to his law practice, his financial fortunes rose as his client list expanded, welcoming many of the most powerful people and institutions in New York. His private life had also taken a happy turn. Over the twenty-four years of his marriage, his wife, Betsy, had presented him with eight children, for whom she had assumed primary responsibility. But he had begun to appreciate anew the joys of family. Of late he had engaged in fewer extramarital distractions—some years before, one of his affairs had exploded in America's first great sex scandal.

And he sought a new contentment at the Grange, the country estate he had completed two years before in Harlem Heights. The events of the morning of July 11, 1804, changed all that. Contrary to his plan, Hamilton discharged his weapon; Burr also fired his. Hamilton's shot crashed into the branch of a cedar tree some six feet over Burr's head, but his opponent's aim was true. The Vice President's bullet penetrated Hamilton's abdomen on his right side, smashing a rib and passing through the liver before being halted by the spine. His lower body paralyzed, the dying man was taken to the mansion of a friend in lower Manhattan.

A message was dispatched to Betsy Hamilton (the gravity of her husband's injury was kept from her at first), and she hurried south from the Grange. The journey of nine miles required almost three hours, but with their seven surviving children, Betsy arrived in time to find she had been summoned to a death watch. His physician dosed him liberally with laudanum to dull the pain, but Hamilton survived only until the next afternoon when, at two o'clock, he breathed his last.

The Owens-Thomas House

Savannah, Georgia

Although born to a noble French family, Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier was certifiably a Founding Father. All Americans seemed to understand that instinctively: after not having set foot on American soil for forty years, "the friend of Washington" received a great outpouring of popular sentiment upon his arrival late in the summer of 1824. Day after day, the sixty-seven-year-old Frenchman met with a universal welcome of speeches, parades, endless toasts, banquets, and cheering crowds.

The Marquis de la Fayette (1757–1834) arrived in America as a nineteen-year-old volunteer (de la Fayette officially became Lafayette after a 1790 French decree abolishing titles). The young man had been a captain in the French dragoons when he embraced the cause of the American revolt, in 1775. Drawing upon his inherited wealth, he purchased and outfitted a ship, La Victoire, which landed him in South Carolina in 1777. A month later he met George Washington, and the two men established an immediate and enduring bond. The Frenchman was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine and experienced the harsh winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge. After a respite in France, where he helped persuade his government to recognize the new nation and provide military aid, he returned to America in 1780 and played a hero's role at Yorktown, in the war's deciding battle. Back in Europe after the close of the war, he was imprisoned in the wake of his country's revolution, but his America connections remained important to him. During Lafayette's incarceration, the wife of the American minister to France, Mrs. James Monroe, arrived at the La Force prison in Paris in the official carriage of the U.S. Legation, demanding—and obtaining—the release of Madame Lafayette.

Much later, Lafayette welcomed the letter from James Monroe. "The whole nation," wrote the President on February 24, 1824, "ardently desire[s] to see you again." Lafayette accepted Monroe's invitation. Instructions were issued by Congress that General Lafayette should expend not one cent on his tour (much of his wealth had been confiscated during the French Revolution). A stop he made in Savannah reflected the kind of celebration he met with. In three days he was feted by the city's leaders, dedicated two monuments, and stayed in one of the city's most elegant homes.

Another sometime visitor to America designed the mansion Lafayette visited, known today as the Owens-Thomas House.

Excerpted from Houses of the Founding Fathers by Hugh Howard, with original photography by Roger Strauss III. Copyright 2007. Published by Artisan, New York. All rights reserved.

Books

Houses of the Founding Fathers: The Men Who Made America and the Way They Lived by Hugh Howard, Artisan, 2007