Where RFK Was Killed, a Diverse Student Body Fulfills His Vision for America

At the site of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, the kids at a Los Angeles public school keep his spirit alive

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/36/47366699-a754-40d3-9ee5-b34e8b420463/janfeb2018_q11_rfkphotoessay.jpg)

His fight may have been cut short before they were born, but he would have recognized the struggles they face: the children of janitors and gardeners, dishwashers and security guards, Mexican, Salvadoran, Korean, Filipino, their adolescent yearnings and hardships percolating through the most densely populated corner of Los Angeles. Shortly after midnight on June 5, 1968, when Senator Robert F. Kennedy delivered his final address, he was standing in their library—then the Embassy Ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel—celebrating his victory in California’s Democratic primary and deploring “the division, the violence, the disenchantment with our society.” Moments later, exiting through the hotel pantry, Kennedy was assassinated by gunman Sirhan Sirhan.

Today more than 4,000 students inhabit those grounds, a campus of six learning centers, kindergarten through 12th grade, that operate as the Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools.

In this era of historical reassessment, of re-examining the figures worthy of a pedestal, RFK seems an enduringly relevant namesake for a school serving the sons and daughters of Los Angeles’ foreign-born working poor. A 40-foot-tall portrait of the slain presidential candidate—painted by Shepard Fairey—looms over a central courtyard. Other murals, plaques and framed black-and-white photographs documenting the life and times of Robert Kennedy crowd the interior walls. A display case of campaign buttons (bearing the slogans “Viva Kennedy” and “Kennedy is the remedy”) graces the foyer of the school’s auditorium—once the site of the Ambassador Hotel’s storied nightclub and celebrity watering hole, the Cocoanut Grove. Even the campus mascot, the Bobcats, is a nod to the liberal folk hero.

“I was reading up about him a few weeks ago,” says 16-year-old Jocelyn Huembes, a junior at RFK’s Ambassador School of Global Leadership. “I read that he was a really social justice-y type of person. And that’s kind of what I believe in.”

Although the tumult of the 1968 presidential race—and the anguish of a second Kennedy assassination—can seem impossibly distant to a teenager in 2018, the thread running from RFK’s agenda to Jocelyn’s hopes and challenges is not hard to untangle. Her mother, who is from El Salvador, works as an in-home caregiver for the elderly; her father, a carpet installer from Nicaragua, was deported when she was a child. Two older brothers, caught up in gangs, have urged her not to repeat their mistakes. Jocelyn takes four AP classes—U.S. history, English, Spanish, environmental science—yet because she and her mom share a studio apartment with another family, she does not have a bedroom or a desk or even a lamp to herself.

“Sometimes I have to turn the lights out because they want to go to sleep,” says Jocelyn, who dreams of becoming a pediatrician. “So if I have a lot of homework that’s really important, I go to the bathroom. I turn on the lights, close the door and sit on the toilet.”

**********

Once a playground for Hollywood royalty, as well as actual kings and queens and sultans from around the globe, the Ambassador, then owned by the J. Myer Schine family, fell on hard times after RFK’s murder, and in 1989 it closed, ending 68 years of pomp and high jinks. The Los Angeles Unified School District, in the grip of an overcrowding crisis, pondered buying the 23.5-acre site. But before the district could act, a developer from New York, Donald Trump, and his business partners purchased the land. “L.A. is going to be very hot,” he said in 1990, unveiling plans to build what would have been the nation’s tallest skyscraper, a 125-story tower, where the hotel once stood.

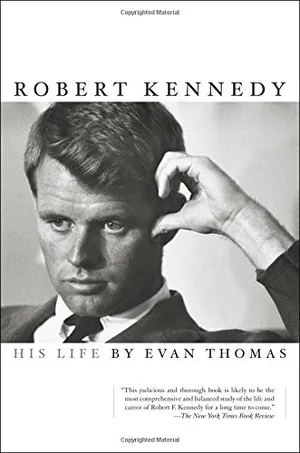

Robert Kennedy: His Life

Thomas's unvarnished but sympathetic and fair-minded portrayal is packed with new details about Kennedy's early life and his behind-the-scenes machinations, including new revelations about the 1960 and 1968 presidential campaigns, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and his long struggles with J. Edgar Hoover and Lyndon Johnson.

Thus began a decade-long legal and public relations brawl: L.A. educators going up against the formidable American enthusiasm for real estate development, while a generation of neighborhood kids who had to slog across town to attend school waited on the sidelines. Seizing the property initially by eminent domain, the school district ultimately prevailed. Trump complained in a deposition that the LAUSD had grabbed the land “as viciously as in Nazi Germany.”

There would be more litigation, brought by preservationists seeking to combat the city’s disposable approach to architecture and even by the attorney for Sirhan Sirhan, long after his conviction, who wanted to perform acoustical tests on the spot where his client ambushed the senator. But the school district, which did not want a crime scene as the centerpiece of its new campus, razed much of the property, including that infamous pantry. “There could be no better memorial to my father than a living memorial that educates the children of this city,” Max Kennedy said at the 2006 groundbreaking for what would become a $579 million project.

**********

So tightly packed are the surrounding neighborhoods of Koreatown and Pico-Union that the student body, 94 percent Latino and Asian, is drawn from just 1.5 square miles. Some are English learners. Most qualify for free lunch. Nearly all who attend college will be the first in their family to do so.

Sumaiya Sabnam, an 11th grader whose mathematical ability and civic activism have already earned her a $20,000 college scholarship, walks to school wearing a hijab, doing her best to tune out the taunts occasionally hurled her way on the street. “Math makes me feel calm, like, ‘OK, there’s an answer to something,’” says Sumaiya, whose father served as a top official for a national political party in their native Bangladesh but here drives a taxi.

Samantha Galindo’s trip home often involves a detour through Beverly Hills, where her Mexican-born father works nights as a janitor—his third job of the day. “Part of the reason I do good in school is that I want to get him out of that life, where he has to work multiple jobs, because it’s starting to take a toll on him,” says Samantha, who does her homework on a jolting Metro bus, then cleans offices alongside her dad until 10 p.m.

Every six months, Aaron Rodriguez shows up at school not knowing whether his mother will make it home from her check-ins with Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials or be deported to Guatemala. “She’ll tell me, ‘Oh, I have court today: If anything happens, I love you,’” says Aaron, a 17-year-old artist and animator, who once poured his feelings into a colored-pencil sketch of a blazing sun trapped behind a barred window. Aaron finds special meaning in another RFK mural, completed by the artist Judy Baca in 2010, that runs 55 feet across the library wall, just above the spot where Kennedy delivered that last victory speech. The image that stays with him, says Aaron, is that of RFK “standing over a crowd of people—and all of them are reaching out toward him and they’re all different skin tones.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.