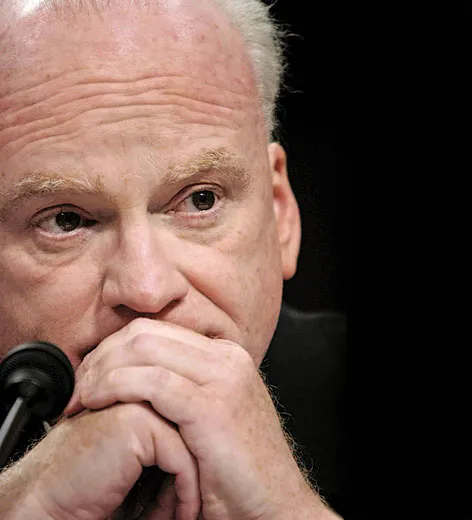

Richard Clarke on Who Was Behind the Stuxnet Attack

America’s longtime counterterrorism czar warns that the cyberwars have already begun—and that we might be losing

The story Richard Clarke spins has all the suspense of a postmodern geopolitical thriller. The tale involves a ghostly cyberworm created to attack the nuclear centrifuges of a rogue nation—which then escapes from the target country, replicating itself in thousands of computers throughout the world. It may be lurking in yours right now. Harmlessly inactive...or awaiting further orders.

A great story, right? In fact, the world-changing “weaponized malware” computer worm called Stuxnet is very real. It seems to have been launched in mid-2009, done terrific damage to Iran’s nuclear program in 2010 and then spread to computers all over the world. Stuxnet may have averted a nuclear conflagration by diminishing Israel’s perception of a need for an imminent attack on Iran. And yet it might end up starting one someday soon, if its replications are manipulated maliciously. And at the heart of the story is a mystery: Who made and launched Stuxnet in the first place?

Richard Clarke tells me he knows the answer.

Clarke, who served three presidents as counterterrorism czar, now operates a cybersecurity consultancy called Good Harbor, located in one of those anonymous office towers in Arlington, Virginia, that triangulate the Pentagon and the Capitol in more ways than one. I had come to talk to him about what’s been done since the urgent alarm he’d sounded in his recent book, Cyber War. The book’s central argument is that, while the United States has developed the capability to conduct an offensive cyberwar, we have virtually no defense against the cyberattacks that he says are targeting us now, and will be in the future.

Richard Clarke’s warnings may sound overly dramatic until you remember that he was the man, in September of 2001, who tried to get the White House to act on his warnings that Al Qaeda was preparing a spectacular attack on American soil.

Clarke later delivered a famous apology to the American people in his testimony to the 9/11 Commission: “Your government failed you.”

Clarke now wants to warn us, urgently, that we are being failed again, being left defenseless against a cyberattack that could bring down our nation’s entire electronic infrastructure, including the power grid, banking and telecommunications, and even our military command system.

“Are we as a nation living in denial about the danger we’re in?” I asked Clarke as we sat across a conference table in his office suite.

“I think we’re living in the world of non-response. Where you know that there’s a problem, but you don’t do anything about it. If that’s denial, then that’s denial.”

As Clarke stood next to a window inserting coffee capsules into a Nespresso machine, I was reminded of the opening of one of the great espionage films of all time, Funeral in Berlin, in which Michael Caine silently, precisely, grinds and brews his morning coffee. High-tech java seems to go with the job.

But saying Clarke was a spy doesn’t do him justice. He was a meta-spy, a master counterespionage, counterterrorism savant, the central node where all the most secret, stolen, security-encrypted bits of information gathered by our trillion-dollar human, electronic and satellite intelligence network eventually converged. Clarke has probably been privy to as much “above top secret”- grade espionage intelligence as anyone at Langley, NSA or the White House. So I was intrigued when he chose to talk to me about the mysteries of Stuxnet.

“The picture you paint in your book,” I said to Clarke, “is of a U.S. totally vulnerable to cyberattack. But there is no defense, really, is there?” There are billions of portals, trapdoors, “exploits,” as the cybersecurity guys call them, ready to be hacked.

“There isn’t today,” he agrees. Worse, he continues, catastrophic consequences may result from using our cyberoffense without having a cyberdefense: blowback, revenge beyond our imaginings.

“The U.S. government is involved in espionage against other governments,” he says flatly. “There’s a big difference, however, between the kind of cyberespionage the United States government does and China. The U.S. government doesn’t hack its way into Airbus and give Airbus the secrets to Boeing [many believe that Chinese hackers gave Boeing secrets to Airbus]. We don’t hack our way into a Chinese computer company like Huawei and provide the secrets of Huawei technology to their American competitor Cisco. [He believes Microsoft, too, was a victim of a Chinese cyber con game.] We don’t do that.”

“What do we do then?”

“We hack our way into foreign governments and collect the information off their networks. The same kind of information a CIA agent in the old days would try to buy from a spy.”

“So you’re talking about diplomatic stuff?”

“Diplomatic, military stuff but not commercial competitor stuff.”

As Clarke continued, he disclosed a belief we’re engaged in a very different, very dramatic new way of using our cyberoffense capability—the story of the legendary cyberworm, Stuxnet.

Stuxnet is a digital ghost, countless lines of code crafted with such genius that it was able to worm its way into Iran’s nuclear fuel enrichment facility in Natanz, Iran, where gas centrifuges spin like whirling dervishes, separating bomb-grade uranium-235 isotopes from the more plentiful U-238. Stuxnet seized the controls of the machine running the centrifuges and in a delicate, invisible operation, desynchronized the speeds at which the centrifuges spun, causing nearly a thousand of them to seize up, crash and otherwise self-destruct. The Natanz facility was temporarily shut down, and Iran’s attempt to obtain enough U-235 to build a nuclear weapon was delayed by what experts estimate was months or even years.

The question of who made Stuxnet and who targeted it on Natanz is still a much-debated mystery in the IT and espionage community. But from the beginning, the prime suspect has been Israel, which is known to be open to using unconventional tactics to defend itself against what it regards as an existential threat. The New York Times published a story that pointed to U.S.-Israeli cooperation on Stuxnet, but with Israel’s role highlighted by the assertion that a file buried within the Stuxnet worm contained an indirect reference to “Esther,” the biblical heroine in the struggle against the genocidal Persians.

Would the Israelis have been foolish enough to leave such a blatant signature of their authorship? Cyberweapons are usually cleansed of any identifying marks—the virtual equivalent of the terrorist’s “bomb with no return address”—so there is no sure place on which to inflict retaliatory consequences. Why would Israel put its signature on a cybervirus?

On the other hand, was the signature an attempt to frame the Israelis? On the other, other hand, was it possible the Israelis had indeed planted it hoping that it would lead to the conclusion that someone else had built it and was trying to pin it on them?

When you’re dealing with virtual espionage, there is really no way to know for sure who did what.

Unless you’re Richard Clarke.

“I think it’s pretty clear that the United States government did the Stuxnet attack,” he said calmly.

This is a fairly astonishing statement from someone in his position.

“Alone or with Israel?” I asked.

“I think there was some minor Israeli role in it. Israel might have provided a test bed, for example. But I think that the U.S. government did the attack and I think that the attack proved what I was saying in the book [which came out before the attack was known], which is that you can cause real devices—real hardware in the world, in real space, not cyberspace—to blow up.”

Isn’t Clarke coming right out and saying we committed an act of undeclared war?

“If we went in with a drone and knocked out a thousand centrifuges, that’s an act of war,” I said. “But if we go in with Stuxnet and knock out a thousand centrifuges, what’s that?”

“Well,” Clarke replied evenly, “it’s a covert action. And the U.S. government has, ever since the end of World War II, before then, engaged in covert action. If the United States government did Stuxnet, it was under a covert action, I think, issued by the president under his powers under the Intelligence Act. Now when is an act of war an act of war and when is it a covert action?

“That’s a legal issue. In U.S. law, it’s a covert action when the president says it’s a covert action. I think if you’re on the receiving end of the covert action, it’s an act of war.”

When I e-mailed the White House for comment, I received this reply: “You are probably aware that we don’t comment on classified intelligence matters.” Not a denial. But certainly not a confirmation. So what does Clarke base his conclusion on?

One reason to believe the Stuxnet attack was made in the USA, Clarke says, “was that it very much had the feel to it of having been written by or governed by a team of Washington lawyers.”

“What makes you say that?” I asked.

“Well, first of all, I’ve sat through a lot of meetings with Washington [government/Pentagon/CIA/NSA-type] lawyers going over covert action proposals. And I know what lawyers do.

“The lawyers want to make sure that they very much limit the effects of the action. So that there’s no collateral damage.” He is referring to legal concerns about the Law of Armed Conflict, an international code designed to minimize civilian casualties that U.S. government lawyers seek to follow in most cases.

Clarke illustrates by walking me through the way Stuxnet took down the Iranian centrifuges.

“What does this incredible Stuxnet thing do? As soon as it gets into the network and wakes up, it verifies it’s in the right network by saying, ‘Am I in a network that’s running a SCADA [Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition] software control system?’ ‘Yes.’ Second question: ‘Is it running Siemens [the German manufacturer of the Iranian plant controls]?’ ‘Yes.’ Third question: ‘Is it running Siemens 7 [a genre of software control package]?’ ‘Yes.’ Fourth question: ‘Is this software contacting an electrical motor made by one of two companies?’” He pauses.

“Well, if the answer to that was ‘yes,’ there was only one place it could be. Natanz.”

“There are reports that it’s gotten loose, though,” I said, reports of Stuxnet worms showing up all over the cyberworld. To which Clarke has a fascinating answer:

“It got loose because there was a mistake,” he says. “It’s clear to me that lawyers went over it and gave it what’s called, in the IT business, a TTL.”

“What’s that?”

“If you saw Blade Runner [in which artificial intelligence androids were given a limited life span—a “time to die”], it’s a ‘Time to Live.’” Do the job, commit suicide and disappear. No more damage, collateral or otherwise.

“So there was a TTL built into Stuxnet,” he says [to avoid violating international law against collateral damage, say to the Iranian electrical grid]. And somehow it didn’t work.”

“Why wouldn’t it have worked?”

“TTL operates off of a date on your computer. Well, if you are in China or Iran or someplace where you’re running bootleg software that you haven’t paid for, your date on your computer might be 1998 or something because otherwise the bootleg 30-day trial TTL software would expire.

“So that’s one theory,” Clarke continues. “But in any event, you’re right, it got out. And it ran around the world and infected lots of things but didn’t do any damage, because every time it woke up in a computer it asked itself those four questions. Unless you were running uranium nuclear centrifuges, it wasn’t going to hurt you.”

“So it’s not a threat anymore?”

“But you now have it, and if you’re a computer whiz you can take it apart and you can say, ‘Oh, let’s change this over here, let’s change that over there.’ Now I’ve got a really sophisticated weapon. So thousands of people around the world have it and are playing with it. And if I’m right, the best cyberweapon the United States has ever developed, it then gave the world for free.”

The vision Clarke has is of a modern technological nightmare, casting the United States as Dr. Frankenstein, whose scientific genius has created millions of potential monsters all over the world. But Clarke is even more concerned about “official” hackers such as those believed to be employed by China.

“I’m about to say something that people think is an exaggeration, but I think the evidence is pretty strong,” he tells me. “Every major company in the United States has already been penetrated by China.”

“What?”

“The British government actually said [something similar] about their own country. ”

Clarke claims, for instance, that the manufacturer of the F-35, our next-generation fighter bomber, has been penetrated and F-35 details stolen. And don’t get him started on our supply chain of chips, routers and hardware we import from Chinese and other foreign suppliers and what may be implanted in them—“logic bombs,” trapdoors and “Trojan horses,” all ready to be activated on command so we won’t know what hit us. Or what’s already hitting us.

“My greatest fear,” Clarke says, “is that, rather than having a cyber-Pearl Harbor event, we will instead have this death of a thousand cuts. Where we lose our competitiveness by having all of our research and development stolen by the Chinese. And we never really see the single event that makes us do something about it. That it’s always just below our pain threshold. That company after company in the United States spends millions, hundreds of millions, in some cases billions of dollars on R&D and that information goes free to China....After a while you can’t compete.”

But Clarke’s concerns reach beyond the cost of lost intellectual property. He foresees the loss of military power. Say there was another confrontation, such as the one in 1996 when President Clinton rushed two carrier battle fleets to the Taiwan Strait to warn China against an invasion of Taiwan. Clarke, who says there have been war games on precisely such a revived confrontation, now believes that we might be forced to give up playing such a role for fear that our carrier group defenses could be blinded and paralyzed by Chinese cyberintervention. (He cites a recent war game published in an influential military strategy journal called Orbis titled “How the U.S. Lost the Naval War of 2015.”)

Talking to Clarke provides a glimpse into the brand-new game of geopolitics, a dangerous and frightening new paradigm. With the advent of “weaponized malware” like Stuxnet, all previous military and much diplomatic strategy has to be comprehensively reconceived—and time is running out.

I left Clarke’s office feeling that we are at a moment very much like the summer of 2001, when Clarke made his last dire warning. “A couple people have labeled me a Cassandra,” Clarke says. “And I’ve gone back and read my mythology about Cassandra. And the way I read the mythology, it’s pretty clear that Cassandra was right.”

Editors Note, March 23, 2012: This story has been modified to clarify that the Natanz facility was only temporarily shut down and that the name “Esther” was only indirectly referenced in the Stuxnet worm.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)