Understanding the Lasting Allure of the Rosetta Stone

An Egyptologist explains the importance of the artifact

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rosetta631.jpg)

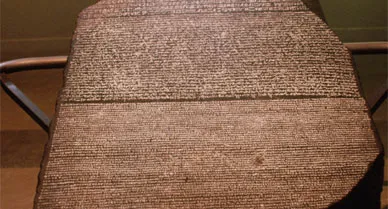

Nearly two centuries after a Frenchman decoded hieroglyphs on an ancient granite stone, opening the proverbial door into the arts, language and literature of Egypt's 3,000-year-old civilization, the allure of the Rosetta stone has yet to fade. Egyptologist John Ray of Cambridge University, the author of a new book, The Rosetta Stone and the Rebirth of Ancient Egypt, explains why.

Today, many people regard the Rosetta stone as little more than a metaphor. How is it that the actual artifact retains its significance?

I think the Rosetta stone is really the key, not simply to ancient Egypt; it's the key to decipherment itself. You've got to think back to before it was discovered. All we knew about the ancient world was Greece, Rome and the Bible.

We knew there were big civilizations, like Egypt, but they'd fallen silent. With the cracking of the Rosetta stone, they could speak with their own voice and suddenly whole areas of history were revealed.

The stone was discovered by the French during a battle with the British in Egypt in 1799 and taken to the tent of General Jacques Menou. When was the stone's significance fully understood?

Even Menou, and some of the people with him, understood it. Napoleon took with him not only soldiers and engineers, but a whole team of scholars.

Now some of the scholars were in the tent with Menou and they could read the Greek. The Greek text is at the bottom of the Rosetta stone. At the very end of the Greek text, it says copies of this decree are written in hieroglyphs and in demotic—which is the language of ordinary Egyptians of that time—and in Greek, and will be placed in every temple.

So that was the "eureka" moment? If you could read the Greek, you could decipher the other two languages?

The Greek text was saying that the funny hieroglyphs at the top of the Rosetta stone said the exact same thing as the Greek text. Suddenly there was a very strong hint that the Rosetta stone was the key.

Did the decoding of the stone instantly open up a window on an entire ancient culture? Did ancient Egypt and all its literature suddenly emerge as a kind of open book, there for the translating?

Yes and no. The real decipherment was done by the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion. Now Champollion, he lived in France after it had lost a world war. If you are on the losing side of a world war, the whole of that society is going to be split with enemies, people distrusting you. So Champollion had a lot of enemies and a lot of people who were simply jealous of him. So it was really a generation before anybody was certain that Champollion had got it right.

The one that knew that he got it right was Champollion himself. Towards the end of his life, he went to Egypt and he went into tombs and temples, and suddenly, he could read those inscriptions—they started to make sense.

And of course, he rushes up and down Egypt going from one temple, one tomb to another and he collapses from overwork. So the trip to Egypt did two things for him. One is that it convinced him that he was right, even if his enemies weren't convinced, and the other thing is it wrecked his health, and it eventually killed him. He died [at age 41, on March 4, 1832] after a string of heart of attacks.

Can you think of any modern-day equivalent of the stone? Has any other encryption had such a powerful effect?

One is the decipherment of Linear B, the script from Crete. That was done by a man called Michael Ventris in the 1950s. Ventris didn't have a Rosetta stone. All he had were the inscriptions themselves. They were short. They were written in a language nobody knew and a script that nobody could read. But bit-by-bit, painstakingly, Ventris cracked the code. The text [was] largely an inventory of agriculture—sheep and goats and things like that. But it's the most amazing decipherment.

Are there other languages that have yet to be translated? Are we still seeking a Rosetta stone for any other culture?

Yes we are. There are three of them. One is the Indus, which are inscriptions from the Punjab in Pakistan, and they haven't been deciphered at all.

The next one is Etruscan, and Etruscan comes from central Italy.

The third one comes from the Sudan and it is called Meroitic. We can read that, as well, because it is written in a kind of Egyptian script. But again we can't identify the language. Now in the last couple of months a Frenchman has published a study reckoning that there, in fact, is a descendent of that language still being spoken in the Nile and the Saharan region somewhere. If he's right, he could be our next Rosetta stone.

If you could imagine it: what if our civilization went the way of the Ancient Egyptians, and our language was lost to future generations, our alphabet rendered indecipherable and our literature unreadable? What do you suppose would turn out to be the Rosetta stone that would decode the 21st Century?

It might well be a big monumental inscription that gets dug up, like a memorial in the cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. Something like that.

But the thing that worries me—really worries me—is that when I was researching my book, I found we know an awful lot about Champollion. We know it because he wrote letters in pen and ink and people kept those letters.

Now, we send e-mails. We do a document, we exit and we save the changes, but the original changes have all gone. And if, at some point, we can't do computer technology, if we can't read disks and things like that, it's lost. We could end up with a real blank, in our generation, in our historical record.

So the next Rosetta stone might actually need to be made of stone because somebody could press a button and that would be it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)