A grand tour of Rome’s iconic sculptures often includes a few staples: the Vatican Museums’ writhing Laocoön; the Capitoline Museums’ Dying Gaul, taking his last breath; and Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina, with those indelible fingerprints left on the goddess’s leg.

But some statues that dot the Italian capital are lesser known. They may not offer much to look at, but they always have a lot to say. Six sculptures in particular, each with its own personality and name, were installed in Rome’s center around the time of the Renaissance and quickly became sites to express political discontent. Locals tacked disgruntled but clever verses onto the busts, writing satires that bemoaned the pope, the city’s bourgeoisie and the corrupt nature of those who held power. As a group, Abate Luigi, Pasquino, Il Facchino, Madama Lucrezia, Marforio and Il Babuino earned the nickname of Rome’s statue parlanti, or talking statues, not because they actually spoke, but because they gave the people a physical way to have an anonymous voice.

Of the six, it is Pasquino, the alleged head and torso of a Greek hero—likely the Mycenaean king Menelaus, carrying the body of fallen warrior Patroclus—that rose to the forefront. Mounted just steps away from the Piazza Navona, the statue stands near the Via Papalis, a papal processional route that was once “one of the most desirable and prestigious [Roman] streets on which to live or to have a business,” says Valeria Cafà, a former conservator at the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/19/ca/19cab351-63fd-4cac-95cc-43e971e19dbd/pasquino1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/11/fb/11fbdcdb-f746-4a40-b2f7-cec0679fd094/pasquino2.jpg)

It was in this area that Cardinal Oliviero Carafa decided to build his estate, Palazzo Orsini, around the turn of the 16th century. During construction of this opulent structure, workers found the “turbaned or helmeted head and muscular upper torso and forelegs” of a sculpture, as well as “merely a slice of torso from below the breast to the upper edge of the pubic hair,” writes Leonard Barkan in Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture.

“The malformed and badly damaged figure was immediately recognized as a marble Hellenistic statue,” wrote scholar Christopher Gilbert in a 2015 paper on Pasquino’s rhetorical role. “Carafa had the statue installed in the Piazza Navona during celebrations for [the Feast of Saint Mark] and instituted a ceremonial routine of adorning it in mythic garb so that each year it assumed an ancient guise.” At the annual feast, workers dressed up and restored the torso and head, often in rudimentary ways, with stucco or papier-mâché.

The statue’s name is inspired by a historical figure who might have been “a schoolmaster, a teacher, a cobbler, a barber or some other vocation entirely,” according to Gilbert. Many chroniclers maintained that the real Pasquino was a tailor to the Roman court, someone who had access to the affairs of elite Romans and could serve as what Gilbert called “a folk messenger of sorts.”

Pasquino’s sculpted namesake occupied an “ambiguous role from the very beginning” of its Renaissance rediscovery, says Maddalena Spagnolo, an art historian at the University of Naples Federico II and the author of Pasquino in the Square: A Statue in Rome Between Art and Vituperation. Rome’s residents used the statue to both “support the pope and at the same time criticize the pope and his inner circle,” Spagnolo adds.

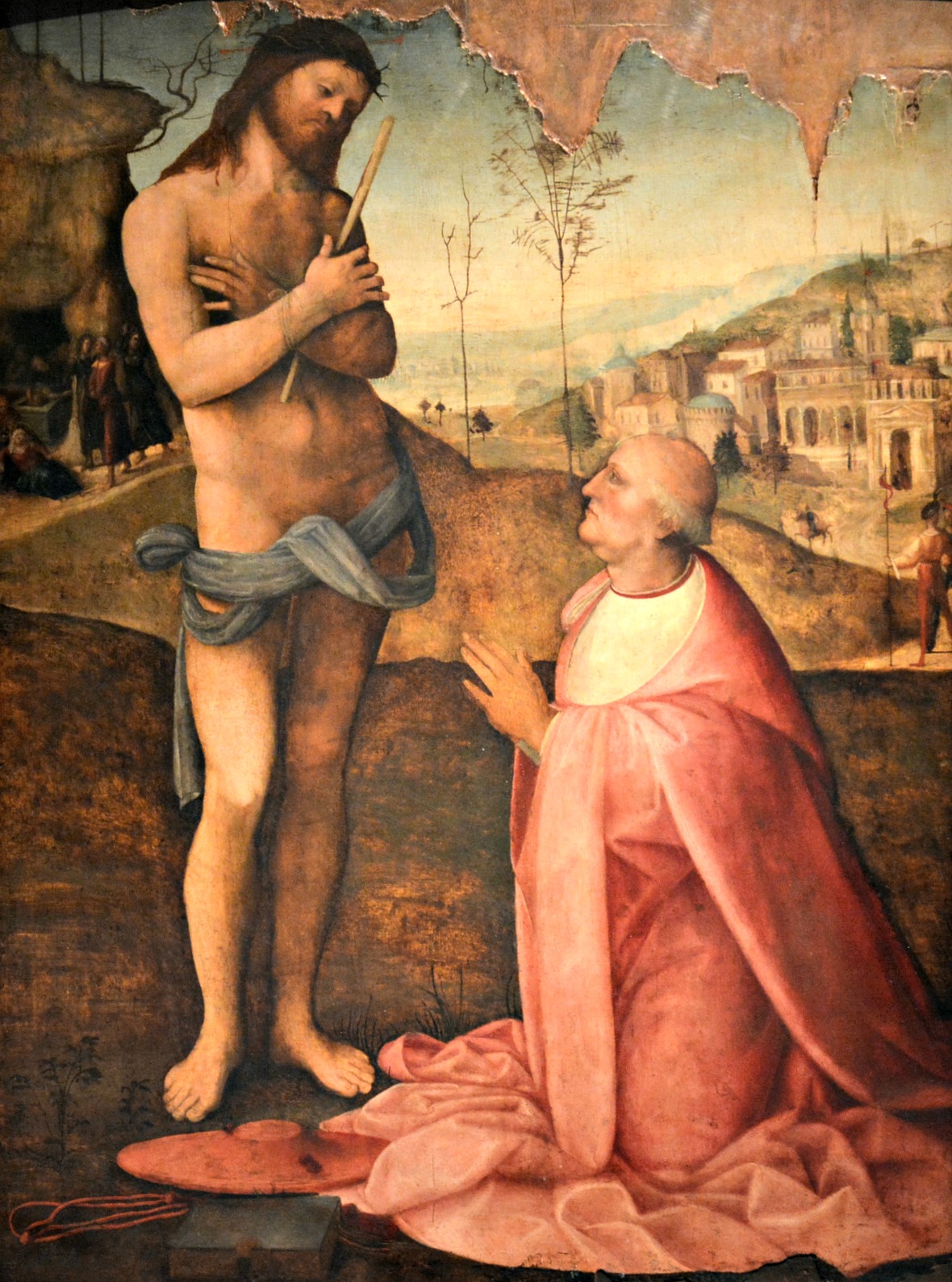

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/df/22/df22227f-0d4d-481b-8002-cc1287dd28b9/pope.jpg)

Despite never serving as pope himself, Carafa was one of the most powerful players in 15th- and 16th-century Rome. Born in Naples in 1430, he was elected cardinal in September 1467 and was known for his “erudition, as well as the integrity and piety of his life,” wrote scholar Anne Reynolds in a 1985 paper. “Although a serious candidate for the papacy on several occasions, Carafa never attained that position. His prestige and authority, however, were unquestionable.”

Pasquino’s mounting in the piazza can be dated to no later than 1501 by literary sources. But Spagnolo speculates that Carafa may have chosen to display Pasquino even earlier, around the time of Pope Alexander VI’s possesso in 1492, when the Christian spiritual leader officially assumed his duties in the city of Rome. On that day, the Borgia pope used the Via Papalis as a ceremonial route, similar to how the ancient Romans conducted their military triumphs through the Campus Martius.

“Everyone who had a house on the Via Papalis was supposed to show joy and agreement for the new pope,” Spagnolo says. Carafa’s installation of Pasquino paid homage to Alexander while simultaneously displaying the cardinal’s “power with this beautiful, huge palace” and accompanying ancient statue.

It didn’t take long for Pasquino to give voice to discontent instead of ceremonial joy. On August 13, 1501, the statue spoke his first words, as recorded in the Latin diary of Johann Burchard, master of ceremonies at the papal court. The lines referenced the Borgia family’s coat of arms (which features an ox), as well as the crest (featuring a wheel) of Cardinal Jorge da Costa, who was thought to be a potential successor to Alexander:

I predicted that you, an ox, would be pope.

And now I say that you will die if you leave this place.

The wheel, keeping pace with the herdsman, will follow.

The same message was then posted throughout different parts of the city, where it certainly had the intended effect.

“The pope was impressed by what he read on the paper on Pasquino, and he was very superstitious,” Spagnolo says. “He read this, and he decided to never leave Rome again.”

The problem with Pasquino has always been to what extent scholars can say that pasquinades, as the messages left near the statue are called, represented the feelings of the people rather than warring political factions. One fact is certain, according to Spagnolo: All of the political invectives against the pope that were tacked onto the talking statues and later published by scholars were “not written by poor people, but by people who were very much [involved in the] papal court.”

Famed satirist and self-described “Scourge of Princes” Pietro Aretino even “claimed Pasquino’s voice as his own,” wrote scholar Laurie Shepard in a 2016 journal article. This dispels the notion of the statue as the true spokesperson of the Roman populace, as he represented only a small segment of those already in the know. In fact, his messages may have been planted to further the aims of the powerful few. As Spagnolo points out, the initial pasquinade that kept Alexander in Rome for the rest of his life was planned by allies inside the Vatican.

Prominent pasquinades often skewered powerful families and the current pope, who was criticized for whatever his preferred method of corruption was. Under Urban VIII, who served as pope from 1623 to 1644 and was a member of the prominent Barberini family, Pasquino offered a succinct bon mot: “What the barbarians did not do, the Barberinis did.” This comment was likely a reaction to Urban’s choice to strip bronze from the Pantheon, “the only ancient Roman building that had survived more or less intact” into the 17th century, as Oxford Reference notes. The pope used the metal to build fortifications at Castel Sant’Angelo, arguing that it “was more important to defend the Holy See than to keep the rain out of the Pantheon porch.”

Laurie Nussdorfer, an emeritus historian at Wesleyan University, says the pasquinade was “a really wonderful comment from … people in the city that these antiquities are theirs. It’s not okay for the pope to just come in there and do things with them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/a4/a4a45ec3-eade-439a-b300-1866dbc6d7ae/marforio_-_palazzo_nuovo_-_musei_capitolini_-_rome_2016_2.jpg)

Yet the perennial tension of where these messages originated persists. Spagnolo attributes the confusion in part to dissimulation, which was the papal court’s modus operandi. In many ways, she explains, the pasquinades were “the product of a cultivated milieu that imitated the language of the mob but expressed the views of one faction … or another and did not aim to attack the authority of the papacy.”

Wherever the satires came from, it was inevitably the common people who faced punishment if they were discovered with a pasquinade in hand. The authors were “impossible to find,” Spagnolo says, but even those who kept the notes in their pocket, repeated them to others or copied them could be found guilty of a crime. As Nussdorfer wrote in a 1987 journal article, in 1636, an aristocrat “lost his head in Rome merely for possessing a manuscript of pasquinades that made fun of Urban VIII’s government.” Proximity to Pasquino and his rhetoric carried inherent danger—but just how much danger depended on the level of power one had.

“It struck me in looking at the history of graffiti that there is a very deep culture of humor in Rome in particular and a deep culture of scratching the surface of public buildings and public statuary,” Gilbert tells Smithsonian magazine. “In the Renaissance itself, which was a moment of revival of art and architecture in an attempt to restore the glory of Rome, … you get a tradition of defacing all of that architecture.”

This defacement ruined Pasquino’s chances of one day being displayed in a museum, where the statue could perhaps be restored to its former glory. In the early 19th century, rampant debate over whether the statue should be moved to a museum ensued. Due to fear of backlash and never-ending pasquinades, and in recognition of the sculpture’s popular status (a descriptor derived from the Latin word populus, or the people), officials decided Pasquino was meant to stay in the piazza.

Pasquino’s fate differs from that of Marforio, the second-most famous of the talking statues and the only one housed in a museum: namely, Rome’s Capitoline Museums. A first-century reclining statue of a male god, likely the personification of the ocean or a river, the statue was discovered in the Forum of Augustus in the 16th century. It was first placed near the Piazza Venezia before being moved to its current home on the Capitoline Hill in the late 1500s. The hulking Marforio had a teasing, almost antagonistic relationship with Pasquino. The pair often sparred with each other in note form. In 1589, when the Tiber River flooded, Pasquino supposedly prayed to be placed up with Marforio in a protected spot. But the verdict was that the Roman people would not allow it. After all, says Spagnolo, Pasquino had a “sad and smelly tongue.”

The talking statues began to seep their way into the quotidian culture of Rome, of note even to foreign visitors. In 1667, Austrian lawyer Joahann Theodor Sprenger wrote about a trio of the sculptures, delineating their various audiences:

Pasquino has two rivals, one the Facchino on Via Lata,

the other Marforio on the Capitoline.

Pasquino is addressed to the aristocrats,

Marforio to the middle class,

Facchino to the peasants.

Much like Pasquino, each artwork carried its own folkloric connotation. Il Facchino portrayed a traditional Renaissance-era worker who toted fresh water from home to home. The sculpture’s origin is unknown, though observers once claimed that Michelangelo himself sculpted the humble water-bearer.

Madama Lucrezia, located by the Palazzo Venezia, is a colossal Roman bust that stands nearly ten feet tall. The statue depicts either the Empress Faustina or, more likely, the Egyptian goddess Isis. She takes her name from Lucrezia d’Alagno, a favorite of Alfonso V of Aragon. When Alfonso died in 1458, d’Alagno came to Rome, settling near the statue’s current home.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e3/57/e3573309-bd4d-4a80-aaaf-ef94e0e0825f/faccino.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/32/f3324057-63f8-413f-8718-c5291e188589/lucrezia.jpg)

In typically gendered fashion, Madama Lucrezia, as the only female talking statue, is occasionally referred to as Pasquino’s paramour, Spagnolo says. But she also held an important political role in the eyes of the people. When French troops established the Roman Republic in 1798 and forced the pope into exile, Madama Lucrezia was toppled off her pedestal and plastered with the words “I can’t stand anymore.”

Abate Luigi, perhaps the most surprising candidate for talking statue status given his lack of a head, may have depicted a magistrate when he was created in the late imperial period. An inscription on the sculpture’s base does some of the talking for him:

I was once a citizen of ancient Rome,

and now everyone calls me Abbot Luigi.

I achieved eternal fame with Marforio and Pasquino with the urban satires.

I was insulted, disgraced and buried,

but here, I have a new life that is finally secure.

The last of the six talking statues is Il Babuino, or the baboon. Part of a fountain, the reclining sculpture of the faun Silenus was commissioned by merchant Alessandro Grandi around 1576. It soon took on a life and reputation of its own, leading locals to rename the street on which it stood from Via Clementina (an homage to Pope Clement VI) to Via del Babuino.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/18/cc/18cce2ec-d2d2-46c6-8803-20b64e936c47/abateluigi.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/da/5fda5e90-33bd-40db-afd5-29f7f8d796f6/babuino.jpg)

What makes Rome’s talking statues so remarkable is how much history they contain. Each sculpture carries the stories of the pasquinades affixed to its surface, as well as its own creation centuries or even millennia ago. It is a testament to Rome’s ever-present vitality that these statues remain in use today. As Google Arts & Culture notes, “Pasquino’s base is still covered in anti-government poems, snarky asides about enemies and complaints about community affairs.”

While scholars can’t confirm that Pasquino was always a site of genuine political protest, he endures as a beacon of hope, a physical space that offers power, however imagined, to the disenfranchised. In one prescient and touching pasquinade, Pasquino addressed his own role of serving as a voice of the people for as long as possible:

Xerxes’ army had not nearly as much wealth

As I have papers: I will soon become a bookseller.

No man in Rome is better than me. I ask for nothing from anyone else;

I am not wordy. I sit here and I’m silent.

You who wish to hang a song on this filled-up wall:

Be quick—I will be naked in a short time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c6/34/c6340ec3-85a8-48d9-a4a8-72871156c972/pasquino_02.jpg)

:focal(960x795:961x796)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b4/a2/b4a2501d-760c-4b50-9e98-c5547dc2fc2e/rome-pasquino-may-2009.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/elizabeth2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/elizabeth2.png)