Ronald Reagan and Moammar Qadhafi

Twenty-five years ago, President Reagan minced no words when he talked about the Libyan dictator

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/United-States-Libya-Moammar-Qadhafi-631.jpg)

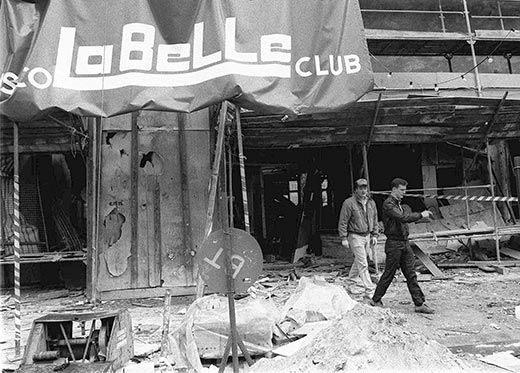

Between 1969, when Col. Moammar Qadhafi took over Libya in a coup, and 2004, when he terminated his country’s nuclear weapons program, U.S.-Libya relations were almost unremittingly hostile. A notable flash point occurred 25 years ago, after a bomb went off on April 5, 1986, in a West Berlin discotheque frequented by U.S. service personnel. Two people, including a U.S. serviceman, were killed, and 204 others were injured. The Reagan administration’s response, both on the ground and at the podium, suggests the tenor of the relationship:

April 9, 1986: news conference

Q: Mr. President, do you have any solid evidence that Qadhafi is responsible for the recent acts of terrorism? And if you are contemplating major retaliation, won’t you be killing a lot of innocent people? I’d like to follow up.

The President: …[W]e have considerable evidence, over quite a long period of time, that Qadhafi has been quite outspoken about his participation in urging on and supporting terrorist acts—a kind of warfare, as he has called it. Right now, however, I can’t answer you specifically on this other, because we’re continuing with our intelligence work and gathering evidence on these most recent attacks, and we’re not ready yet to speak on that...

Q: Mr. President, I know you must have given it a lot of thought, but what do you think is the real reason that Americans are the prime target of terrorism? Could it be our policies?

The President: Well, we know that this mad dog of the Middle East has a goal of a world revolution, Muslim fundamentalist revolution, which is targeted on many of his own Arab compatriots. And where we figure in that, I don’t know. Maybe we’re just the enemy because—it’s a little like climbing Mount Everest—because we’re here. But there’s no question but that he has singled us out more and more for attack, and we’re aware of that. As I say, we’re gathering evidence as fast as we can.

That evidence included intercepted communications implicating the Libyan government in the attack, prompting President Reagan to order air strikes on ground targets there.

April 14, 1986: address to the nation

President Reagan: At 7 o’clock this evening Eastern time air and naval forces of the United States launched a series of strikes against the headquarters, terrorist facilities and military assets that support Muammar Qadhafi’’s subversive activities. The attacks were concentrated and carefully targeted to minimize casualties among the Libyan people, with whom we have no quarrel. From initial reports, our forces have succeeded in their mission...

The evidence is now conclusive that the terrorist bombing of La Belle discotheque was planned and executed under the direct orders of the Libyan regime. On March 25, more than a week before the attack, orders were sent from Tripoli to the Libyan People’s Bureau in East Berlin to conduct a terrorist attack against Americans to cause maximum and indiscriminate casualties. Libya’s agents then planted the bomb. On April 4 the People’s Bureau alerted Tripoli that the attack would be carried out the following morning. The next day they reported back to Tripoli on the great success of their mission...

Colonel Qadhafi is not only an enemy of the United States. His record of subversion and aggression against the neighboring states in Africa is well documented and well known. He has ordered the murder of fellow Libyans in countless countries. He has sanctioned acts of terror in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, as well as the Western Hemisphere. Today we have done what we had to do. If necessary, we shall do it again. It gives me no pleasure to say that, and I wish it were otherwise. Before Qadhafi seized power in 1969, the people of Libya had been friends of the United States. And I’m sure that today most Libyans are ashamed and disgusted that this man has made their country a synonym for barbarism around the world. The Libyan people are a decent people caught in the grip of a tyrant.

The following October, Bob Woodward of the Washington Post reported that the Reagan administration had “launched a secret and unusual campaign of deception designed to convince Libyan leader Moammar Qadhafi that he was about to be attacked again by U.S. bombers and perhaps be ousted in a coup.” Under questioning from White House reporters, Reagan challenged the report (the substance of which the White House would confirm the next day) and changed the subject to Qadhafi.

October 2, 1986: news conference

Q: Well, Mr. President, just to follow up on this: The main burden of the story suggests that your White House, specifically your national security adviser, constructed an operation whereby the free press in this country was going to be used to convey a false story to the world, namely, that Qadhafi was planning new terrorist operations and that we were going to hit him again—or we might hit him again—full well knowing that this was not true. Now, if that’s the case, then the press is being used, and we will in the future not know—when we’re being told information from the White House—whether it’s true or it’s not.

The President: Well, any time you get any of those leaks, call me. [Laughter] I’ll be happy to tell you which ones are honest or not. But no, this was wrong and false. Our position has been one of which—after we took the action we felt we had to take and I still believe was the correct thing to do—our position has been one in which we would just as soon have Mr. Qadhafi go to bed every night wondering what we might do. And I think that’s the best position for anyone like that to be in. Certainly, we did not intend any program in which we were going to suggest or encourage him to do more things, or conduct more terrorist attacks. We would hope that the one thing that we have done will have turned him off on that for good.

Qadhafi frustrated the president’s hope for decades. Notably, a Libyan intelligence agent was convicted in the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, which killed 259 people on the plane, including 189 U.S. citizens, and 11 more on the ground. But in 2003, the Libyan government accepted responsibility for the bombing and set aside funds to pay damages to the victims’ survivors. The following year—in the months before Reagan died, at age 93, on June 5—Libya gave up its nuclear weapons program and normalized relations with the United States.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)