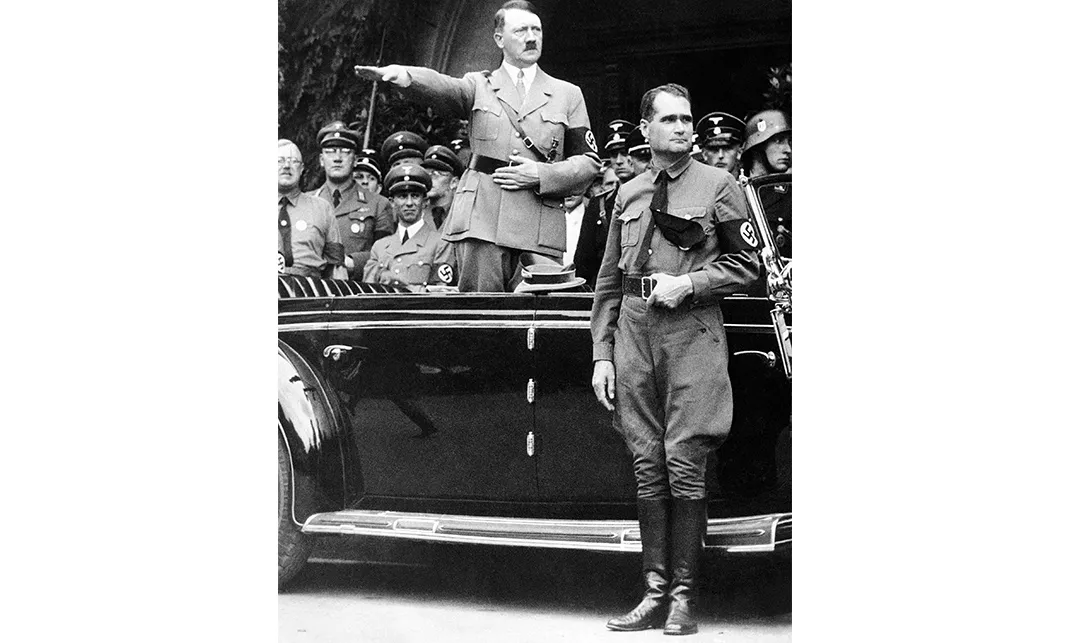

Rudolf Hess’ Tale of Poison, Paranoia and Tragedy

Why are packets of food that belong to the Nazi war criminal sitting in a Maryland basement?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/13/5d13cf7c-50a6-4882-a9c8-6255065fd6a0/oct14_h04_rudolfhess.jpg)

In August 1945, an Army major named Douglas Kelley was handed one of the most sought-after assignments in his profession: examining the most prominent Nazis who’d been taken prisoner of war. Kelley, a psychiatrist trained at Berkeley and Columbia, had been treating American soldiers in Europe for combat stress. He saw his new job as a chance to “learn the why of the Nazi success,” he later wrote in his book 22 Cells in Nuremberg, “so we can take steps to prevent the recurrence of such evil.”

Before the historic war-crimes trials in Nuremberg, Kelley spent five months interviewing the 22 captive defendants at length, giving them Rorschach and other tests and collecting possessions they’d surrendered. He particularly enjoyed matching wits with Hermann Goering, Hitler’s second in command, whom he treated for an addiction to paracodeine.

It was at the Nuremberg prison that Kelley interviewed Rudolf Hess, beginning in October 1945. Hess was a special case. Once Adolf Hitler’s deputy and designated successor, he’d been in custody for more than four years, far longer than the others. When Kelley talked to him, Hess would shuffle around his cell, slip into and out of amnesia and stare into space. But when Kelley asked why he’d made his ill-fated solo flight to England in the spring of 1941, Hess was clear: The British and the Germans should not be fighting each other, but presenting a united front against the Soviets. He had come to broker a peace.

“I thought of the colossal naiveté of this Nazi mind,” Kelley wrote in an unpublished statement, “imagining you could plant your foot on the throat of a nation one moment and give it a kiss on both cheeks the next.” Hess saw himself as an envoy, and was shocked when the British took him prisoner. As the months passed, he came to suspect that his captors were trying to poison him, so he took to wrapping bits of his food and medications in brown paper and sealing them with a wax stamp, intending to have them analyzed for proof that he was being abused. He also wrote a statement about his captivity that totaled 37 double-spaced pages.

When Kelley returned to the United States, he boxed up everything from his work at Nuremberg—his notes, the tests, inmates’ belongings, including X-rays of Hitler’s skull, paracodeine capsules confiscated from Goering, and Hess’ food packets and statement—and took it home to Santa Barbara, California.

“It was that Nazi stuff in the basement,” says his son Douglas Kelley Jr., a retired postal worker. “We all knew it was there.” The archive is now in his basement, in suburban Maryland, between boxes of family photographs and his niece’s artwork. Some of its contents have been published—Jack El-Hai’s recent book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist includes a portrait of Goering that the former Reichsmarschall autographed for Kelley. But the younger Kelley allowed Smithsonian to photograph Hess’ food packets for the first time. The packets, and Hess’ statement, provide a glimpse into the mind of a man who, the elder Kelley wrote in 22 Cells, “will continue to live always in the borderlands of insanity.”

When he first landed in Scotland, Hess wrote, the British people “took care of me very well. They...put a rocking chair near the fireplace and offered me tea. Later, when I was surrounded by British soldiers, a young Tommy got up and gave me a bottle of milk which he had taken along for his guard duty.”

The next day, he requested a meeting with the Duke of Hamilton, in the mistaken belief that the duke would be sympathetic to Hess’ peace plan. Hamilton said he would inform King George VI, but nothing ever came of it. Over the next few weeks, Hess was moved from Scotland to a military installation at Mytchett Place, about 40 miles southwest of London.

“When I arrived...I instinctively distrusted the food,” Hess wrote. “Thus I did not eat or drink anything on the first day.” He grudgingly agreed to the suggestion that he eat with his doctors and guards for reassurance that he wasn’t being poisoned, but then, he said, he was offered food different from theirs. “Once, when I was careless and drank a little bit of milk by myself,” he wrote, “a short time later I got dizzy, had a terrific headache and could not see straight any more. Soon thereafter I got into an hilarious mood and increased nervous energy became apparent. A few hours later, this gave way to the deepest depression and weakness. From then on I had milk and cheese brought into my room every day but merely to deceive the people that I was eating that stuff.”

Of course Hess was interrogated. “My correct answers evidently caused disappointment,” he wrote. “However, loss of memory which I simulated gradually caused satisfaction.” So he feigned amnesia more and more. Eventually, “I got to such a state that apparently I could not remember anything...that was further back than a few weeks.” He concluded that his questioners were trying “to weaken my memory” before a meeting with Lord Chancellor Simon, Britain’s highest-ranking jurist, that June.

To prepare for the meeting, Hess fasted for three days to clear his mind. “I was well enough for a conference lasting two and a half hours, even though I was still under the influence of a small amount of brain poison.” The lord chancellor, however, found Hess’ peace plan unconvincing and his complaints of maltreatment incredible. He left, Hess wrote, “convinced I had become a victim of prison psychosis.”

Soon it wasn’t just brain poison in his food. Hess believed that the British put a rash-inducing powder in his laundry, and that the Vaseline they gave him to treat the rash contained heart poison. He believed the guards added bone splinters and gravel to his meals to break his teeth. He attributed his sour stomach to their lacing his food with so much acid “the skin came loose and hung in little bits from my palate.” In desperation, he wrote, “I scratched lime from the walls in the hope that this would neutralize the other stuff but I was not successful.” When his stomach pains disappeared, it was because “my body readjusted” and so “they stopped giving me any more acid.”

In November 1941, Hess sent a letter asking for a meeting with the Swiss envoy in London, who he thought could intervene on his behalf. “I had hardly mailed the letter,” Hess recalled, “when again huge quantities of brain poison were put in my food to destroy my memory.” The Swiss envoy visited Hess, several times, and agreed to take samples of his medications for a laboratory analysis. When the tests determined that nothing was wrong, Hess concluded that “it was an easy matter for the secret service...to give orders that nothing should be found in them for reasons important to the conduct of the war.”

As the months passed, Hess tried twice to kill himself, by jumping over a staircase railing and by stabbing himself with a butter knife. His obsession with food was unrelenting. When the Swiss envoy visited in August 1943, Hess had lost 40 pounds. In November 1944, Hess petitioned the British for a “leave of absence” in Switzerland to restore his health. It was denied.

When Hess was transferred to Nuremberg in October 1945, he relinquished his food packets under protest and asked Kelley to make sure they were safe. Kelley determined that while Hess suffered from “a true psychoneurosis, primarily of the hysterical type, engrafted on a basic paranoid and schizoid personality, with amnesia, partly genuine and partly feigned,” he was fit to stand trial. More than half a dozen other psychiatrists, from Russia, France, England and the United States, agreed.

Most of the other Nuremberg defendants were sentenced to death, but Hess, convicted of two counts related to crimes against peace, was sentenced to life in prison.

Douglas Kelley Sr. concluded that the Nuremberg defendants represented not a specifically Nazi pathology, but that “they were simply creatures of their environment, as all humans are.” Kelley killed himself on New Year’s Day 1958, swallowing a cyanide capsule in front of his family. (Goering, too, had taken cyanide, after he was sentenced to hang.) Hess spent 40 years complaining of the food and his health at Spandau Prison in western Berlin before he succeeded at what he’d tried twice before. He hanged himself with an extension cord on August 17, 1987. He was 93.