Ruth McGinnis: The Queen of Billiards

Back when pool was a serious sport that grabbed the attention of the nation, one woman smoked the competition

:focal(626x487:627x488)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/3e/253e29fe-c298-45df-a88b-47380fc6f2e0/image014.jpg)

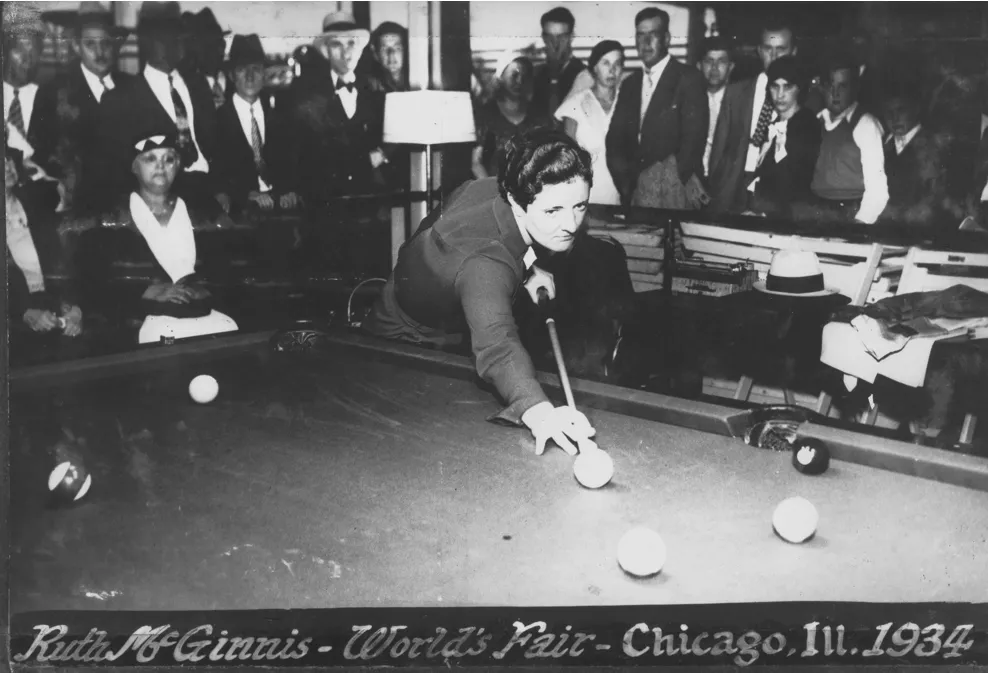

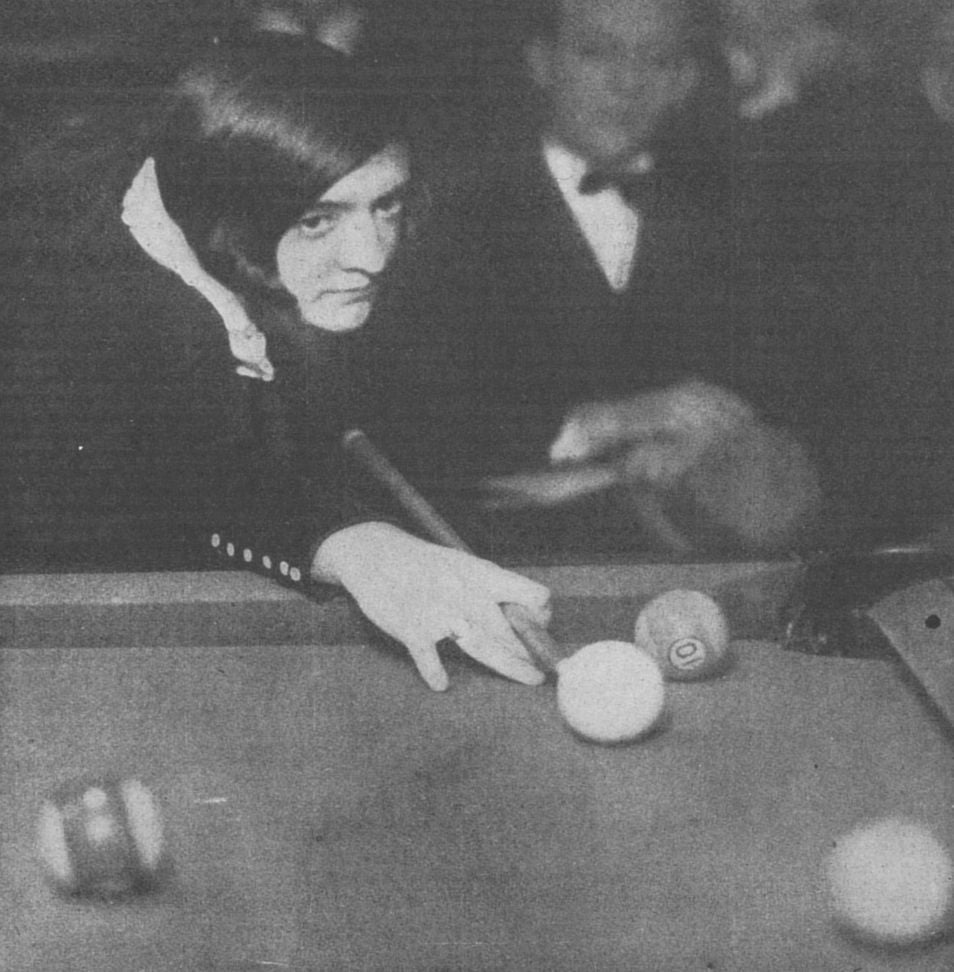

One January day in 1938, a slight, wide-eyed woman named Ruth McGinnis walked into the Arcadia, a pool hall in Washington, D.C, where six of the district’s most accomplished players waited to play her. McGinnis powdered her hands. She picked up her cue. The men tried to act nonchalant, but as they watched McGinnis dispatch their friends one after another, they shifted nervously from foot to foot.

McGinnis played a straightforward game, not chatting or joking with anyone as she played, the balls clacking cleanly as she cleared the table. The manager teased that he should borrow a bowling ball from the alley next door and paint a big 8 on it, so the men stood a chance. But it was a weak joke. And she beat them all.

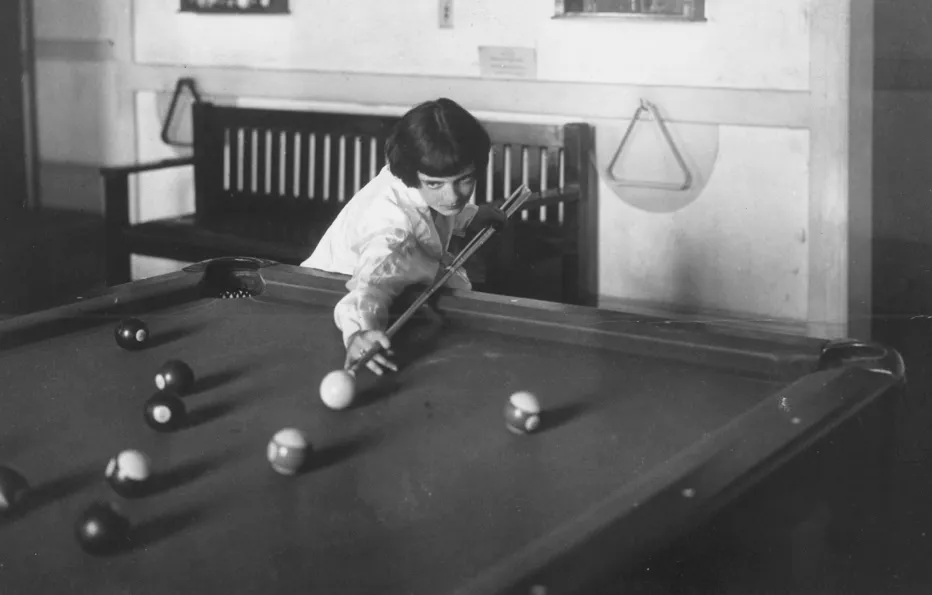

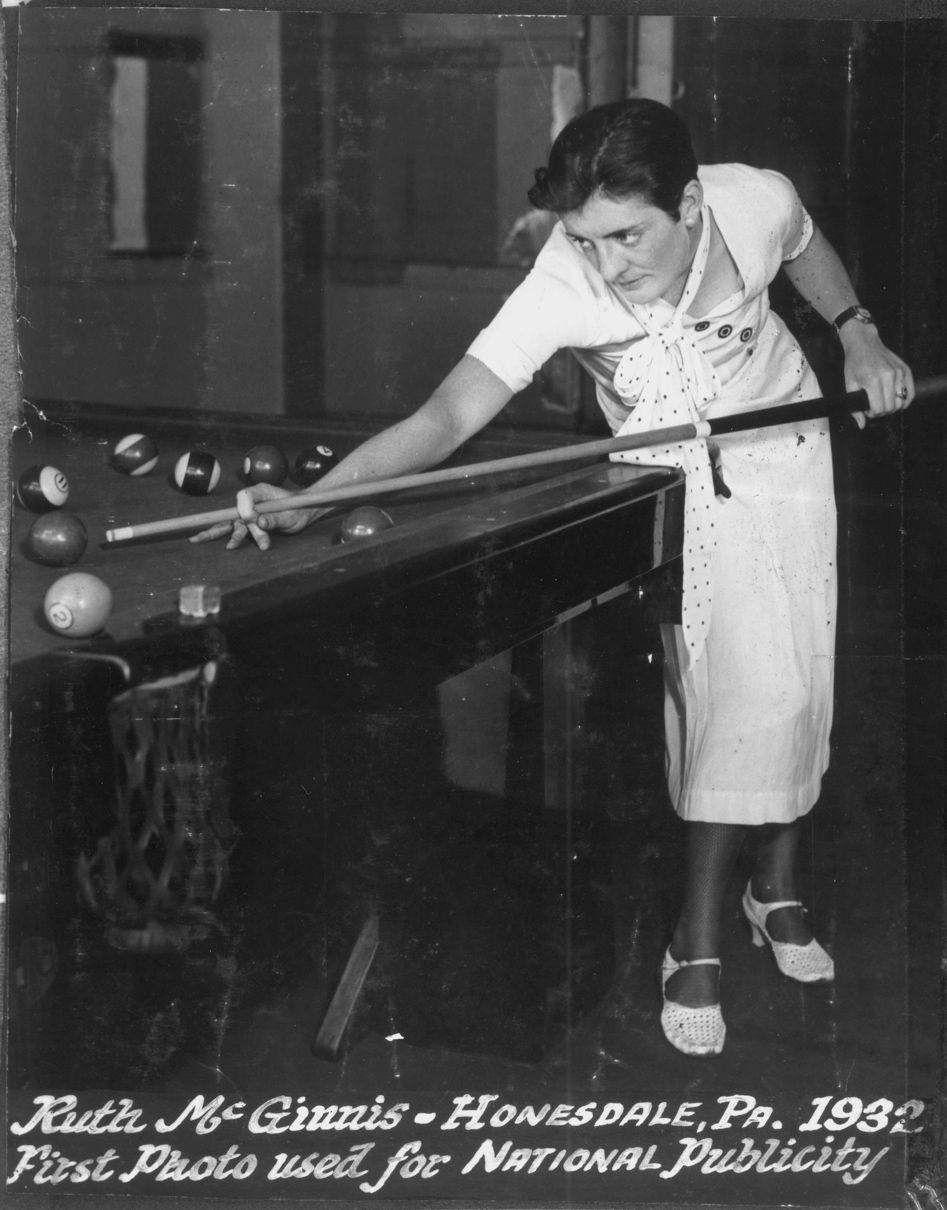

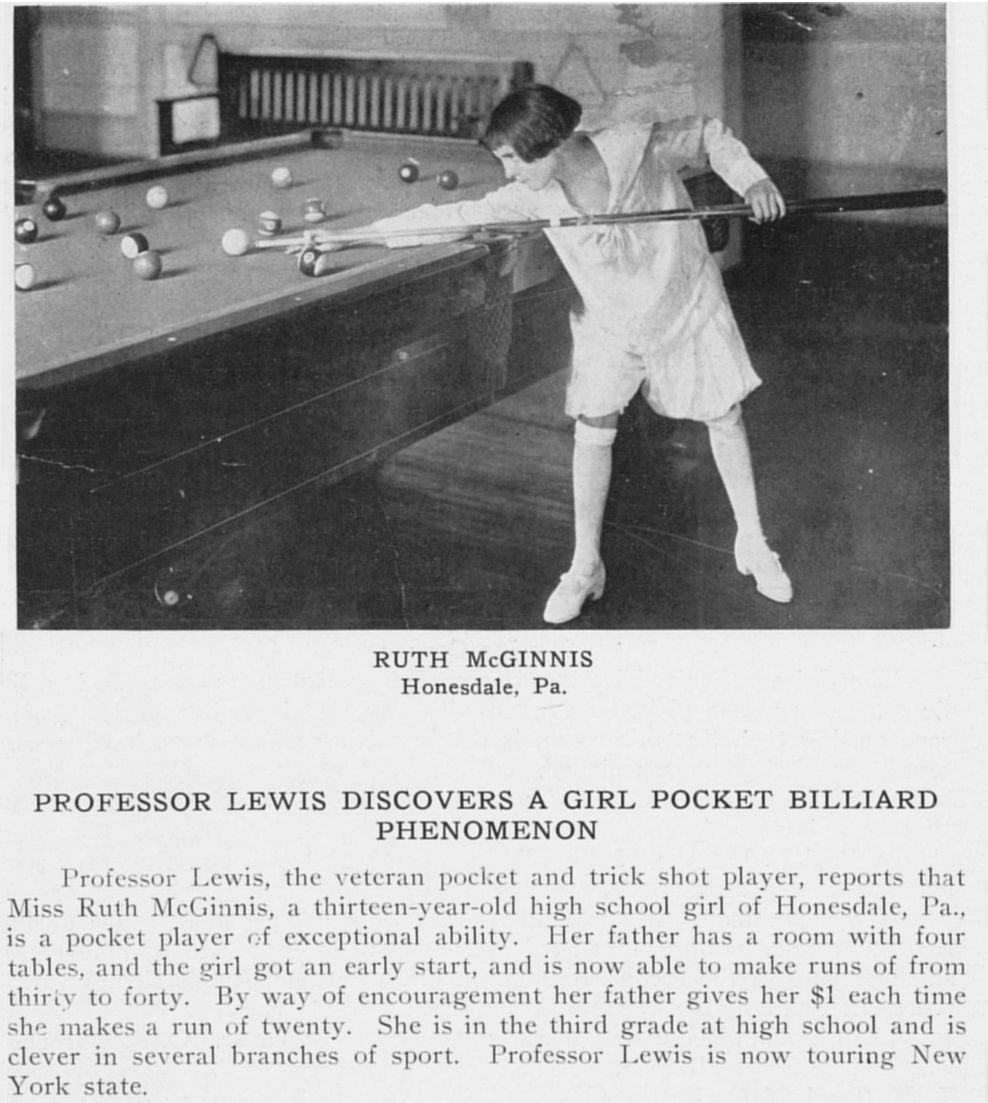

That was just an average day at the tables for McGinnis, who triumphed in the male enclave of the pool room, earning her the nickname "The Queen of Billiards." Born in 1910, she started playing in her family's Honesdale, Pennsylvania, barbershop at 7 years old: her father kept two pool tables for waiting customers, and a soapbox for tiny Ruth to stand on. She excelled.

Pool was a big deal in those days. "You have to understand that pool back in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s was in a very different space in this country than it is now," says pool historian and author R. A. Dyer. "Now the sport is relegated to bars and play in leagues, but most prominent pool players nowadays--their names are not household words. But during McGinnis' age this was not the case. You could find plenty of stories about Ruth McGinnis and other pool players in the New York Times."

McGinnis' game, popular in the 1930s, was straight pool, which is what Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason play in the iconic film The Hustler. (Today, if you walk into an American bar with pool tables, patrons are likely playing 8-ball.) In straight pool, the player calls what ball she will try for—stripes or solids doesn't matter. If she sinks 14 balls in a row or "runs a 14," she can use the 15th to start into another rack and continue shooting.

"When [McGinnis] was 10 or so she ran a 47," says Dyer, "and most pool players that can find their way around a pool table are never going to run a 47 in their entire lives, let alone at age 10, just to put that into context."

National and world title-holder Mary Kenniston has met people over the years who knew McGinnis. "In addition to playing 'like a man.' which was a compliment in those days, she ran hundreds of balls," says Kenniston. "To run a hundred balls is like the milestone for a straight pool player. That means, he's a really good player. Or she's a really good player."

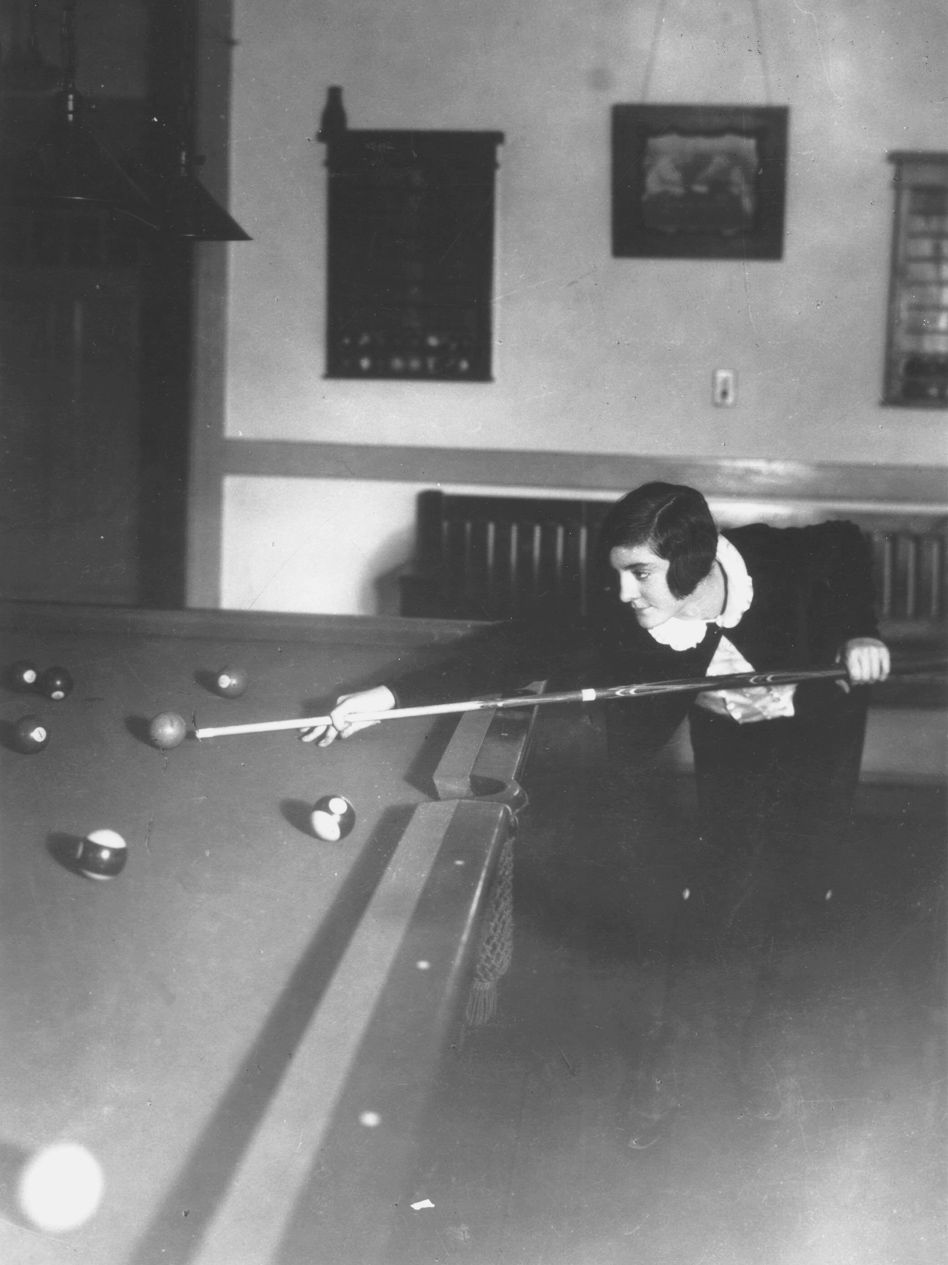

McGinnis studied to become a physical education teacher, but when she graduated from Stroudsburg Teachers' College in 1932, the Great Depression was ravaging America. Lower-end pool halls had become magnets for seediness, where unemployed men whiled hours away. "In the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s, and up until the ’50s, pool rooms were almost exclusively a male domain, associated with men behaving badly," says Dyer. Women faced harassment and struggled to find mentors.

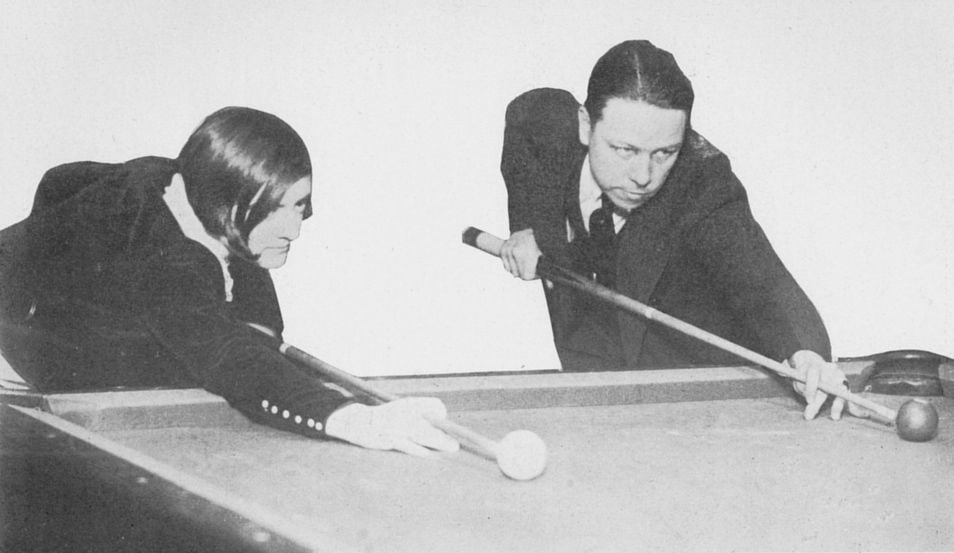

But McGinnis, a rare left-hander, found work shooting pool anyway. She logged close to 28,000 miles a season touring the country as part of an industry movement to paint pool as wholesome, says Dyer. The program was called "Better Billiards" and the sponsor, the National Billiard Association of America, paid for McGinnis to visit well-established halls to give a brief talk about pool, do some trick shots, and then take on the local champion. In 1936, Recreation Academy in New Brunswick, New Jersey, put up a special grandstand, and a crowd gathered to watch McGinnis take on local legend Jack Lenhart. The women in the audience clapped as she pocketed ten balls, one after the other, leaving Lenhart in the dust.

"Miss Ruth McGinnis Shows Top Form to Beat Lenhart," ran a headline the next day. Other headlines also show that she didn't require an introduction. "Ruth McGinnis Twice Defeats [World Champion] Ralph Greenleaf," wrote the Allentown, Pennsylvania. Morning Call in 1937. "Miss McGinnis Victor Over Two Boston Men," ran a 1936 headline in the Boston Globe. "Ruth M'Ginnis Wins Cue Test," said a 1938 Baltimore Sun headline. Others marveled at her being a woman: "One Miss Who Knows Her Cue," in 1937; and "Hand That Rocks Cradle Also Wields Mean Cue." Reporters called her Susie Cue, and Queen of Billiards.

This attention countered social norms of the time, when women athletes were considered "a spectacle—not serious athletes," says Alison M. Wrynn, a professor at California State, Long Beach who studies sports and gender. She says that the most accomplished female athlete of this era, Babe Didrikson Zaharias, medalled in track and field at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, but that during most of the rest of the 1930s, struggled to find a sport to play professionally. (She eventually helped found the LPGA.) Didrikson was such a predominant athlete that promoters believed she could compete with McGinnis at pool, and that the combined celebrity would prove a draw. So in 1933, the two played a much-hyped six-day pool match. Didrikson was no match for McGinnis, who won, 400-62. (Later, McGinnis, who also excelled at other sports, toured with Didrikson's basketball team.)

Tournament play of the time was restricted to men, who competed for purses that Dyer says could reach into the thousands of dollars, not including the side wagers that players might place. Sports reporters covered high-level matches, and hundreds of fans would gather to watch high-level competition in bigger pool halls, says Dyer, who notes that world professional champion Ralph Greenleaf performed for thousands of spectators, and even in a Broadway theater.

McGinnis, who was paid for her part on the tour, played primarily in exhibition contests, which could have anywhere from dozens to hundreds of audience members. Despite opposition to her invasion of a men’s club—one reporter wrote that old timers would “turn over in their graves if they had learned that pool had gone petticoat”—McGinnis kept going, and winning. In 1937, she beat Greenleaf in a 6-block match. From 1933 to 1939, McGinnis only lost 29 out of 1,532 matches, a winning percentage of 0.976. She had a high run of 128. With accomplishments like that, she was considered the World Women’s Champion.

The lack of an official designation wasn't easy for her. She sometimes played local female champions, but they were never anywhere near a match for her. "I have to play men because there is no competition among women," she explained in 1932. "Women can enter tournaments in every other sport. That makes my title of world's champion seem meaningless."

Contemporary commentary reflected the pressure McGinnis felt. She noted that because she had to maintain propriety, ten-foot tables (rather than her preferred nine-foot ones) irked her. A male player could "put his legs all over the table—I can't," she said. One reporter wrote that McGinnis was probably single because "while most men will brave the rolling pin, few would allow the reach advantage offered by a pool cue." And while a sports columnist wrote that Greenleaf acknowledged in 1938 that she was "a great woman player, probably the best," he added, "she's still just a woman and can't top the run of good men players."

The criticism may have stung, but it didn't stop her from proving him wrong. "She proved that women could play almost as well as men in a game that previously had been exclusively male--straight pool," says Michael Shamos, the author of The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. Dyer agrees. "The fact that she couldn't play in tournaments was not a knock on her ability," he says. "It was a knock on where we were as a nation at that time."

"I get a big kick out of beating men because they always seem so anxious to show their superiority," McGinnis said in 1940. "Most of them play as though it were a matter of life or death. If I played that way I'd be a case for an institution in a few weeks."

McGinnis competed in the New York state meet in 1942, the first woman in a major tournament. She defeated a man in a third-round match, but lost in the end, 125 to 82. In 1948, she became the first woman ever to compete for the world pocket billiard title. She died in 1974, and was inducted into the Billiard Congress of America’s Hall of Fame in 1976. A sign honoring her stands in Honesdale, and today, McGinnis is seen as a forbear of female pool greats like Dorothy Wise, Jean Balukas, Kenniston, Allison Fisher, and Jeanette Lee.

"Let's put it this way," says Kenniston. "98 percent of [men] don't think a woman can beat them doing anything. And the other two percent are just so stunned that they'd want to pay and watch you play."

"Ruth McGinnis was America's first truly important woman pool player," Dyer says. "Keep in mind that women for much of the sport's history were not fixtures in public poolrooms, nor were they even welcome in them. In fact, many of pool's followers then believed that women were physically and mentally incapable of excelling at the sport. And then Ruth McGinnis came along and proved all of them wrong, and in the most dramatic way imaginable. She made headlines throughout America as a winning sensation, as a woman who could stand up to the very best men. In this very important way Ruth McGinnis broke down barriers in what had been a quintessentially male endeavor."

For her part, McGinnis didn't see herself as particularly gifted. She thought others could do what she did. "Women should play this game," McGinnis told a reporter. "They have a fine touch, and that's what is required."

"She wasn't just eye candy," says Kenniston. "She could play, is what I was told. And that's a quote. I heard that a thousand times. She could really play."