Sabotage in New York Harbor

Explosion on Black Tom Island packed the force of an earthquake. It took investigators years to determine that operatives working for Germany were to blame

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111101100023munitions-explosion-new-york-harbor.jpg)

All was dark and quiet on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, not far from the Statue of Liberty, when small fires began to burn on the night of July 30, 1916. Some guards on the island sent for the Jersey City Fire Department, but others fled as quickly as they could, and for good reason: Black Tom was a major munitions depot, with several large “powder piers.” That night, Johnson Barge No. 17 was packed with 50 tons of TNT, and 69 railroad freight cars were storing more than a thousand tons of ammunition, all awaiting shipment to Britain and France. Despite America’s claim of neutrality in World War I, it was no secret that the United States was selling massive quantities of munitions to the British.

The guards who fled had the right idea. Just after 2:00 a.m., an explosion lit the skies—the equivalent of an earthquake measuring up to 5.5 on the Richter scale, according to a recent study. A series of blasts were heard and felt some 90 miles in every direction, even as far as Philadelphia. Nearly everyone in Manhattan and Jersey City was jolted awake, and many were thrown from their beds. Even the heaviest plate-glass windows in Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn shattered, and falling shards of glass preceded a mist of ash from the fire that followed the explosion. Immigrants on nearby Ellis Island had to be evacuated.

Peter Raceta, the captain of a flatbottom barge in the harbor, was in the cabin watching the fire on Black Tom with two other men. “When the explosion came, it seemed as if it was from above—zumpf!—like a Zeppelin bomb,” he told a reporter from the New York Times. “There were five or six other lighters alongside mine at the dock, and a tug was just coming up to drag us away.… I don’t know what became of the tug or the other lighters. It looked as if they all went up in the air.” Of the two men he was with, she said, “I didn’t see where they went, but I think they must be dead.”

Watchmen in the Woolworth building in Lower Manhattan saw the blast, and “thinking their time had come, got down on their knees and prayed,” one newspaper reported. The Statue of Liberty took more than $100,000 worth of damage; Lady Liberty’s torch, which was then open to visitors who could climb an interior ladder for a spectacular view, has been closed ever since. Onlookers in Manhattan watched as munition shells rocketed across the water and exploded a mile from the fires on Black Tom Island.

Flying bullets and shrapnel rendered firefighters powerless. Doctors and nurses arrived on the scene and tended to dozens of injured. The loss of life, however, was not great: Counts vary, but fewer than ten people perished in the explosions. However, the damage was estimated at more than $20 million, (nearly half a billion dollars today), and investigations eventually determined that the Black Tom explosions resulted from an enemy attack—what some historians regard as the first major terrorist attack on the United States by a foreign power.

Firefighters were unable to fight the fires until the bullets and shrapnel stopped flying. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In the days after the blasts, confusion reigned. Police arrested three railroad-company officials on charges of manslaughter, on the assumption that the fires began in two freight cars. Then guards at the pier were taken in for questioning; on the night of the explosions, they had lit smudge pots to keep mosquitoes away, and their carelessness with the pots was believed to have started the fires. But federal authorities could not trace the fire to the pots, and reports ultimately concluded that the blasts must have been accidental—even though several suspicious factory explosions in the United States, mostly around New York, pointed toward German spies and saboteurs. As Chad Millman points out in his book, The Detonators, there was a certain naivete at the time—President Woodrow Wilson could not bring himself to believe that Germans might be responsible for such destruction. Educated, industrious and neatly dressed, German-Americans’ perceived patriotism and commitment to life in America allowed them to integrate into society with less initial friction than other ethnic groups.

One of those newcomers to America was Count Johann Von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to Washington. He arrived in 1914 with a staff not of diplomats, but of intelligence operatives, and with millions of dollars earmarked to aid German war efforts by any means necessary. Von Bernstorff not only helped obtain forged passports for Germans who wanted to elude the Allied blockade, he also funded gun-running efforts, the sinking of American ships bringing supplies to Britain, and choking off supplies of phenol, used in the manufacture of explosives, in a conspiracy known as the Great Phenol Plot.

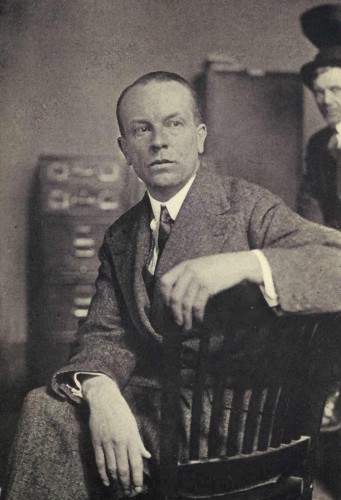

One of his master spies was Franz Von Rintelen, who had a “pencil bomb” designed for his use. Pencil bombs were cigar-sized charges filled with acids placed in copper chambers; the acids would ultimately eat their way through the copper and mingle, creating intense, silent flames. If designed and placed properly, a pencil bomb could be timed to detonate days later, while ships and their cargo were at sea. Von Rintelen is believed to have attacked 36 ships, destroying millions of dollars worth of cargo. With generous cash bribes, Von Rintelen had little problem gaining access to piers—which is how Michael Kristoff, a Slovak immigrant living in Bayonne, New Jersey, is believed to have gotten to the Black Tom munitions depot in July of 1916.

German Master Spy Franz Von Rintelen and his "pencil bomb" were responsible for acts of sabotage in the United States during World War I. Photo: Wikipedia

Investigators later learned from Kristoff’s landlord that he kept odd hours and sometimes came home at night with filthy hands and clothing, smelling of fuel. Along with two German saboteurs, Lothar Witzke and Kurt Jahnke, Kristoff is believed to have set the incendiary devices that caused the mayhem on Black Tom.

But it took years for investigators to piece together the evidence against the Germans in the bombing. The Mixed Claims Commission, set up after World War I to handle damage claims by companies and governments affected by German sabotage, awarded $50 million to plaintiffs in the Black Tom explosion—the largest damage claim of any in the war. Decades would pass, however, before Germany settled it. In the meantime, landfill projects eventually incorporated Black Tom Island into Liberty State Park. Now nothing remains of the munitions depot save a plaque marking the explosion that rocked the nation.

Sources

Books: The Detonators: The Secret Plot to Destroy America and an Epic Hunt for Justice by Chad Millman, Little, Brown and Company, 2006. American Passage: This History of Ellis Island by Vincent J. Cannato, HarperCollins, 2009. Sabotage at Black Tom: Imperial Germany’s Secret War in America, 1914-1917, Algonquin Books, 1989.

Articles: “First Explosion Terrific” New York Times, July 31, 1916. “How Eyewitnesses Survived Explosion” New York Times, July 31, 1916. “Woolworth Tower Watchmen Pray” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 31, 1916. “Many Explosions Since War Began” New York Times, July 31, 1916. “Millions of Persons Heard and Felt Shock” New York Times, July 31, 1916. “N.Y. Firemen Work in Rain of Bullets” New York Times, July 31, 1916. “No Evidence of Plot in New York Explosion, Federal Agents Assert” Washington Post, July 31, 1916. “Statue of Liberty Damaged by Giant Ammunition Explosions” Washington Post, July 31, 1916. “Rail Heads Face Arrest in Pier Blast at N.Y.” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 1, 1916. “Black Tom Explosion” Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security, by Adrienne Wilmoth Lerner. http://www.faqs.org/espionage/Bl-Ch/Black-Tom-Explosion.html The Kiaser Sows Destruction: Protecting the Homeland the First Time Around by Michael Warner. Central Intelligence Agency https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol46no1/article02.html

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)