Sacrifice Amid the Ice: Facing Facts on the Scott Expedition

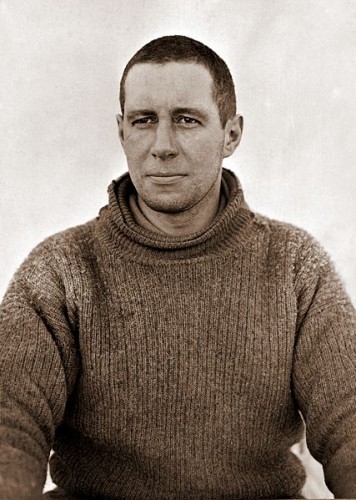

Captain Lawrence Oates wrote that if Robert Scott’s team didn’t win the race to the South Pole, “we shall come home with our tails between our legs”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120516011032Lawrence_Oates_captain-scott-small.jpg)

![]()

For Lawrence Oates, the race to the South Pole had a portentous start. Just two days after the Terra Nova Expedition left New Zealand in November 1910, a violent storm killed two of the 19 ponies in Oates’s care and nearly sank the ship. His journey ended almost two years later, when he stepped out of a tent and into the teeth of an Antarctic blizzard after uttering ten words that would bring tears of pride to mourning Britons. During the long months in between, Oates’s concern for the ponies paralleled his growing disillusionment with the expedition’s leader, Robert Falcon Scott.

Oates had paid one thousand pounds for the privilege of joining Scott on an expedition that was supposed to combine exploration with scientific research. It quickly became a race to the South Pole after the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, already at sea with a crew aboard the Fram, abruptly changed his announced plan to go to the North Pole. “BEG TO INFORM YOU FRAM PROCEEDING ANTARCTIC—AMUNDSEN,” read the telegram he sent to Scott. It was clear that Amundsen would leave the collecting of rock specimens and penguin eggs to the Brits; he wanted simply to arrive first at the pole and return home to claim glory on the lecture circuit.

Born in 1880 to a wealthy English family, Lawrence Oates attended Eton before serving as a junior officer in the Second Boer War. A gunshot wound in a skirmish that earned Oates the nickname “Never Surrender” shattered his thigh, leaving his left leg an inch shorter than his right.

Still, Robert Scott wanted Oates along for the expedition, but once Oates made it to New Zealand, he was startled to see that a crew member (who knew dogs but not horses) had already purchased ponies in Manchuria for five pounds apiece. They were “the greatest lot of crocks I have ever seen,” Oates said. From past expeditions, Scott had deduced that white or gray ponies were stronger than darker horses, though there was no scientific evidence for that. When Oates told him that the Manchurian ponies were unfit for the expedition, Scott bristled and disagreed. Oates seethed and stormed away.

Inspecting the supplies, Oates quickly surmised that there was not enough fodder, so he bought two extra tons with his own money and smuggled the feed aboard the Terra Nova. When, to great fanfare, Scott and his crew set off from New Zealand for Antarctica on November 29, 1910, Oates was already questioning the expedition in letters home to his mother: “If he gets to the Pole first we shall come home with our tails between our legs and make no mistake. I must say we have made far too much noise about ourselves all that photographing, cheering, steaming through the fleet etc. etc. is rot and if we fail it will only make us look more foolish.” Oates went on to praise Amundsen for planning to use dogs and skis rather than walking beside horses. “If Scott does anything silly such as underfeeding his ponies he will be beaten as sure as death.”

After a harrowingly slow journey through pack ice, the Terra Nova arrived at Ross Island in Antarctica on January 4, 1911. The men unloaded and set up base at Camp Evans, as some crew members set off in February on an excursion in the Bay of Whales, off the Ross Ice Shelf—where they caught sight of Amundsen’s Fram at anchor. The next morning they saw Amundsen himself, crossing the ice at a blistering pace on his dog sled as he readied his animals for an assault on the South Pole, some 900 miles away. Scott’s men had had nothing but trouble with their own dogs, and their ponies could only plod along on the depot-laying journeys they were making to store supplies for the pole run.

Given their weight and thin legs, the ponies would plunge through the top layer of snow; homemade snowshoes worked only on some of them. On one journey, a pony fell and the dogs pounced, ripping at its flesh. Oates knew enough to keep the ponies away from the shore, having learned that several ponies on Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition (1907-1909) had fallen dead after eating salty sand there. But he also knew some of his animals simply would not hold up on any lengthy journey. He suggested to Scott that they kill the weaker ones and store the meat for the dogs at depots on the way to the pole. Scott would have none of it, even though he knew that Amundsen was planning to kill many of his 97 Greenland dogs for the same purpose.

“I have had more than enough of this cruelty to animals,” Scott replied, “and I’m not going to defy my feelings for the sake of a few days’ march.”

“I’m afraid you’ll regret it, Sir,” Oates answered.

The Terra Nova crews continued with their depot-laying runs, with the dogs becoming “thin as rakes” from long days of heavy work and light rations. Two ponies died of exhaustion during a blizzard. Oates continued to question Scott’s planning. In March of 1911, with expedition members camped on the ice in McMurdo Sound, a crew woke in the middle of the night to a loud cracking noise; they left their tents to discover they were stranded on a moving ice floe. Floating beside them on another floe were the ponies.

The men hopped over to the animals and began moving them from floe to flow, trying to get them back to the Ross Ice Shelf to safety. It was slow work, as they often had to wait for another floe to drift close enough to make any progress at all.

Then a pod of killer whales began circling the floe, poking their heads out of the water to see over the floe’s edge, their eyes trained on the ponies. As Henry Bowers described in his diary, “the huge black and yellow heads with sickening pig eyes only a few yards from us at times, and always around us, are among the most disconcerting recollections I have of that day. The immense fins were bad enough, but when they started a perpendicular dodge they were positively beastly.”

Oates, Scott and others came to help, with Scott worried about losing his men, let alone his ponies. Soon, more than a dozen orcas were circling, spooking the ponies until they toppled into the water. Oates and Bowers tried to pull them to safety, but they proved too heavy. One pony survived by swimming to thicker ice. Bowers finished off the rest with a pick axe so the orcas at least wouldn’t eat them alive.

“These incidents were too terrible,” Scott wrote.

Worse was to come. In November 1911, Oates left Cape Evans with 14 other men, including Scott, for the South Pole. The depots had been stocked with food and supplies along the route. “Scott’s ignorance about marching with animals is colossal,” Oates would write. “Myself, I dislike Scott intensely and would chuck the whole thing if it were not that we are a British expedition.… He is not straight, it is himself first, the rest nowhere.”

Scott's party at the South Pole, from left to righ:, Wilson, Bowers, Evans, Scott and Oates. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Unlike Scott, Amundsen paid attention to every detail, from the proper feeding of both dogs and men to the packing and unpacking of the loads they would carry, to the most efficient ski equipment for various mixtures of snow and ice. His team traveled twice as fast as Scott’s, which had resorted to manhauling their sledges.

By the time Scott and his final group of Oates, Bowers, Edward Wilson and Edgar Evans had reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912, they saw a black flag whipping in the wind. “The worst has happened,” Scott wrote. Amundsen had beaten them by more than a month.

“The POLE,” Scott wrote. “Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected. We have had a horrible day—add to our disappointment a head wind 4 to 5, with a temperature -22 degrees, and companions laboring on with cold feet and hands.… Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have labored to it without the reward of priority.”

The return to Camp Evans was sure to be “dreadfully long and monotonous,” Scott wrote. It wasn’t monotonous. Edgar Evans took a fall on February 4th and became “dull and incapable,” according to Scott; he died two weeks later after another fall near the Beardmore Glacier. The four survivors were suffering from frostbite and malnutrition, but seemingly constant blizzards, temperatures of 40 degrees below zero and snowblindness limited their progress back to camp.

Oates, in particular, was suffering. His old war wound now practically crippled him, and his feet were “probably gangrene,” according to Ross D.E. MacPhee’s Race to the End: Amundsen, Scott and the Attainment of the South Pole. Oates asked Scott, Bowers and Wilson to go on without him, but the men refused. Trapped in their tent during a blizzard on March 16th or 17th (Scott’s journal no longer recorded dates), with food and supplies nearly gone, Oates stood up. “I am just going outside and may be some time,” he said—his last ten words.

The others knew he was going to sacrifice himself to increase their odds of returning safely, and they tried to dissuade him. But Oates didn’t even bother to put his boots on before disappearing into the storm. He was 31. “It was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman,” Scott wrote.

Two weeks later, Scott himself was the last to go. “Had we lived,” Scott wrote in one of his last diary entries, “I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale.”

Roald Amundsen was already telling his tale, one of triumph and a relatively easy journey to and from the South Pole. Having sailed the Fram into Tasmania earlier in March, he knew nothing of Scott’s ordeal—only that there had been no sign of the Brits at the pole when the Norwegians arrived. Not until October 1912 did the weather improve enough for a relief expedition from Terra Nova to head out in search of Scott and his men. The next month they came upon Scott’s last camp and cleared the snow from the tent. Inside, they discovered the three dead men in their sleeping bags. Oates’s body was never found.

Sources

Books: Ross D.E. MacPhee, Race to the End: Amundsen, Scott and the Attainment of the South Pole, American Museum of Natural History and Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2010. Robert Falcon Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition: The Journals, Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996. David Crane, Scott of the Antarctic: A Biography, Vintage Books, 2005. Roland Huntford, Scott & Amundsen: The Race to the South Pole, Putnam, 1980.

For Lawrence Oates, the race to the South Pole had a portentous start. Just two days after the Terra Nova Expedition left New Zealand in November 1910, a violent storm killed two of the 19 ponies in Oates’s care and nearly sank the ship. His journey ended almost two years later, when he stepped out of a tent and into the teeth of an Antarctic blizzard after uttering ten words that would bring tears of pride to mourning Britons. During the long months in between, Oates’s concern for the ponies paralleled his growing disillusionment with the expedition’s leader, Robert Falcon Scott.

Oates had paid one thousand pounds for the privilege of joining Scott on an expedition that was supposed to combine exploration with scientific research. It quickly became a race to the South Pole after the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, already at sea with a crew aboard the Fram, abruptly changed his announced plan to go to the North Pole. “BEG TO INFORM YOU FRAM PROCEEDING ANTARCTIC—AMUNDSEN,” read the telegram he sent to Scott. It was clear that Amundsen would leave the collecting of rock specimens and penguin eggs to the Brits; he wanted simply to arrive first at the pole and return home to claim glory on the lecture circuit.

Born in 1880 to a wealthy English family, Lawrence Oates attended Eton before serving as a junior officer in the Second Boer War. A gunshot wound in a skirmish that earned Oates the nickname “Never Surrender” shattered his thigh, leaving his left leg an inch shorter than his right.

Still, Robert Scott wanted Oates along for the expedition, but once Oates made it to New Zealand, he was startled to see that a crew member (who knew dogs but not horses) had already purchased ponies in Manchuria for five pounds apiece. They were “the greatest lot of crocks I have ever seen,” Oates said. From past expeditions, Scott had deduced that white or gray ponies were stronger than darker horses, though there was no scientific evidence for that. When Oates told him that the Manchurian ponies were unfit for the expedition, Scott bristled and disagreed. Oates seethed and stormed away.

Inspecting the supplies, Oates quickly surmised that there was not enough fodder, so he bought two extra tons with his own money and smuggled the feed aboard the Terra Nova. When, to great fanfare, Scott and his crew set off from New Zealand for Antarctica on November 29, 1910, Oates was already questioning the expedition in letters home to his mother: “If he gets to the Pole first we shall come home with our tails between our legs and make no mistake. I must say we have made far too much noise about ourselves all that photographing, cheering, steaming through the fleet etc. etc. is rot and if we fail it will only make us look more foolish.” Oates went on to praise Amundsen for planning to use dogs and skis rather than walking beside horses. “If Scott does anything silly such as underfeeding his ponies he will be beaten as sure as death.”

After a harrowingly slow journey through pack ice, the Terra Nova arrived at Ross Island in Antarctica on January 4, 1911. The men unloaded and set up base at Camp Evans, as some crew members set off in February on an excursion in the Bay of Whales, off the Ross Ice Shelf—where they caught sight of Amundsen’s Fram at anchor. The next morning they saw Amundsen himself, crossing the ice at a blistering pace on his dog sled as he readied his animals for an assault on the South Pole, some 900 miles away. Scott’s men had had nothing but trouble with their own dogs, and their ponies could only plod along on the depot-laying journeys they were making to store supplies for the pole run.

Given their weight and thin legs, the ponies would plunge through the top layer of snow; homemade snowshoes worked only on some of them. On one journey, a pony fell and the dogs pounced, ripping at its flesh. Oates knew enough to keep the ponies away from the shore, having learned that several ponies on Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition (1907-1909) had fallen dead after eating salty sand there. But he also knew some of his animals simply would not hold up on any lengthy journey. He suggested to Scott that they kill the weaker ones and store the meat for the dogs at depots on the way to the pole. Scott would have none of it, even though he knew that Amundsen was planning to kill many of his 97 Greenland dogs for the same purpose.

“I have had more than enough of this cruelty to animals,” Scott replied, “and I’m not going to defy my feelings for the sake of a few days’ march.”

“I’m afraid you’ll regret it, Sir,” Oates answered.

The Terra Nova crews continued with their depot-laying runs, with the dogs becoming “thin as rakes” from long days of heavy work and light rations. Two ponies died of exhaustion during a blizzard. Oates continued to question Scott’s planning. In March of 1911, with expedition members camped on the ice in McMurdo Sound, a crew woke in the middle of the night to a loud cracking noise; they left their tents to discover they were stranded on a moving ice floe. Floating beside them on another floe were the ponies.

The men hopped over to the animals and began moving them from floe to flow, trying to get them back to the Ross Ice Shelf to safety. It was slow work, as they often had to wait for another floe to drift close enough to make any progress at all.

Then a pod of killer whales began circling the floe, poking their heads out of the water to see over the floe’s edge, their eyes trained on the ponies. As Henry Bowers described in his diary, “the huge black and yellow heads with sickening pig eyes only a few yards from us at times, and always around us, are among the most disconcerting recollections I have of that day. The immense fins were bad enough, but when they started a perpendicular dodge they were positively beastly.”

Oates, Scott and others came to help, with Scott worried about losing his men, let alone his ponies. Soon, more than a dozen orcas were circling, spooking the ponies until they toppled into the water. Oates and Bowers tried to pull them to safety, but they proved too heavy. One pony survived by swimming to thicker ice. Bowers finished off the rest with a pick axe so the orcas at least wouldn’t eat them alive.

“These incidents were too terrible,” Scott wrote.

Worse was to come. In November 1911, Oates left Cape Evans with 14 other men, including Scott, for the South Pole. The depots had been stocked with food and supplies along the route. “Scott’s ignorance about marching with animals is colossal,” Oates would write. “Myself, I dislike Scott intensely and would chuck the whole thing if it were not that we are a British expedition.… He is not straight, it is himself first, the rest nowhere.”

Scott's party at the South Pole, from left to righ:, Wilson, Bowers, Evans, Scott and Oates. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Unlike Scott, Amundsen paid attention to every detail, from the proper feeding of both dogs and men to the packing and unpacking of the loads they would carry, to the most efficient ski equipment for various mixtures of snow and ice. His team traveled twice as fast as Scott’s, which had resorted to manhauling their sledges.

By the time Scott and his final group of Oates, Bowers, Edward Wilson and Edgar Evans had reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912, they saw a black flag whipping in the wind. “The worst has happened,” Scott wrote. Amundsen had beaten them by more than a month.

“The POLE,” Scott wrote. “Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected. We have had a horrible day—add to our disappointment a head wind 4 to 5, with a temperature -22 degrees, and companions laboring on with cold feet and hands.… Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have labored to it without the reward of priority.”

The return to Camp Evans was sure to be “dreadfully long and monotonous,” Scott wrote. It wasn’t monotonous. Edgar Evans took a fall on February 4th and became “dull and incapable,” according to Scott; he died two weeks later after another fall near the Beardmore Glacier. The four survivors were suffering from frostbite and malnutrition, but seemingly constant blizzards, temperatures of 40 degrees below zero and snowblindness limited their progress back to camp.

Oates, in particular, was suffering. His old war wound now practically crippled him, and his feet were “probably gangrene,” according to Ross D.E. MacPhee’s Race to the End: Amundsen, Scott and the Attainment of the South Pole. Oates asked Scott, Bowers and Wilson to go on without him, but the men refused. Trapped in their tent during a blizzard on March 16th or 17th (Scott’s journal no longer recorded dates), with food and supplies nearly gone, Oates stood up. “I am just going outside and may be some time,” he said—his last ten words.

The others knew he was going to sacrifice himself to increase their odds of returning safely, and they tried to dissuade him. But Oates didn’t even bother to put his boots on before disappearing into the storm. He was 31. “It was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman,” Scott wrote.

Two weeks later, Scott himself was the last to go. “Had we lived,” Scott wrote in one of his last diary entries, “I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale.”

Roald Amundsen was already telling his tale, one of triumph and a relatively easy journey to and from the South Pole. Having sailed the Fram into Tasmania earlier in March, he knew nothing of Scott’s ordeal—only that there had been no sign of the Brits at the pole when the Norwegians arrived. Not until October 1912 did the weather improve enough for a relief expedition from Terra Nova to head out in search of Scott and his men. The next month they came upon Scott’s last camp and cleared the snow from the tent. Inside, they discovered the three dead men in their sleeping bags. Oates’s body was never found.

Sources

Books: Ross D.E. MacPhee, Race to the End: Amundsen, Scott and the Attainment of the South Pole, American Museum of Natural History and Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2010. Robert Falcon Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition: The Journals, Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996. David Crane, Scott of the Antarctic: A Biography, Vintage Books, 2005. Roland Huntford, Scott & Amundsen: The Race to the South Pole, Putnam, 1980.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)