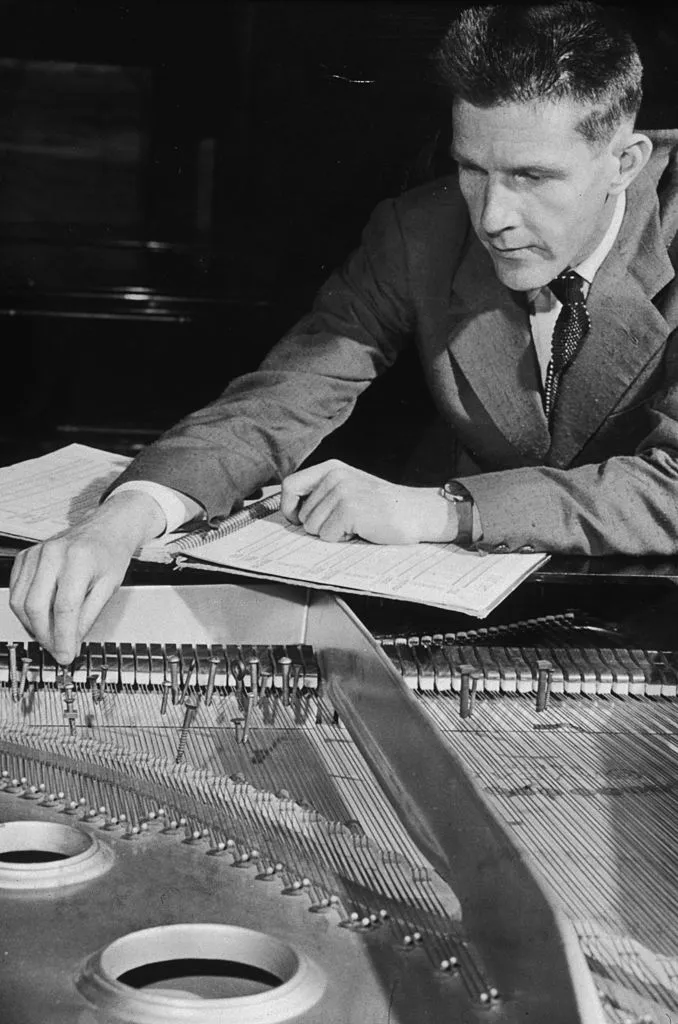

How Composer John Cage Transformed the Piano—With the Help of Some Household Objects

With screws and bolts placed between its strings, the ‘prepared piano’ offers up a wide range of sounds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/f6/89f63979-935b-41b8-ab8a-2414b7ce502a/hauschka_performs_prepared_piano.jpg)

Every musician has a particular set of tasks and warm-ups before a performance or practice session—oiling the valves, rosining the bow, tuning, long tones, scales, stretches. For Kelly Moran, a composer and pianist based in New York City, this ritual includes peering inside the lid of the piano to carefully place screws and bolts of various sizes in between the delicate strings.

Moran composes for a technique known as the prepared piano, in which everyday household items are used to alter the sound of any given note on the instrument. While screws and bolts are Moran’s objects of choice, other potential preparations include paper clips, straws and pencil erasers. Placed on the 230 strings inside the piano, these objects muffle or choke the timbre of the sound produced when a key on the keyboard is pressed.

Moran was first exposed to prepared piano while studying composition and music technology at the University of Michigan, and was immediately intrigued by its transformative potential. “The instrument that I had been playing my entire life suddenly sounded completely different and fresh, and it was something that really interested me,” she says. “That’s when I got interested in working the piano and generating sound in unconventional ways.”

In an age in which music is increasingly produced exclusively using electronic sounds, and live instruments, when they do appear, are so often electronically manipulated, the prepared piano plays the unique role of an instrument that creates sounds that feel electronically altered using an acoustic manipulation.

While composers such as Henry Cowell experimented with manipulating the strings of the piano during the early 1900s, the history of prepared piano as it is understood today begins with the American composer John Cage. Born in Los Angeles in 1912, Cage is one of the most celebrated and provocative avant-garde composers of the 20th century. His oeuvre can only be summarized as one of truly wild and wide-ranging experimentation. His most famous work, "4’33’’", instructs the performer to sit in silence for the duration of the four minute, 33 second piece; in other pieces, Cage abandons traditional music notation in favor of multicolored squiggly lines and shapes, as in his 1958 vocal work "Aria."

Cage struggled with the harmonic limitations of the piano, and not being able to play between the twelve pitches of the chromatic scale. His background in the music scene of the West coast led him towards an interest in tonalities outside of what the traditional piano had to offer. “California, unlike the East coast, was very much connected to the Orient,” says Laura Kuhn, the director of The John Cage Trust. “So his influences really came from being exposed to the ideas of the far East, rather than the West.”

As Cage explains in a foreword to Richard Bunger’s The Well-Prepared Piano, he was inspired to begin altering the piano while working as an accompanist for a dance class in Seattle. Tasked with writing music to accompany a performance by the dancer Syvilla Fort, Cage lamented the lack of room on stage for percussion instruments. “I decided that what was wrong was not me but the piano,” he writes in the foreword.

Cage stuck to screws and bolts for "Bacchanale," his 1940 composition and the first for prepared piano, but he gradually grew more ambitious in his preparations. His most famous prepared piano work, "Sonatas and Interludes," is a collection of 20 shorter works with objects including screws, bolts, nuts, rubber and plastic. His choice of preparations adds a strikingly percussive nature to the lower register of the piano, while the prepared notes in the upper register have a darkened, ethereal timbre.

Cage gave very specific instructions as to how the instrument should be prepared, detailing exactly what sort of object should be used on each string and how far along the string each object should be placed. According to Kuhn, he would at times sit in on rehearsals of his prepared piano works and advise the pianist on making adjustments to the preparations.

Moran is far from the only contemporary composer creating music with the prepared piano technique. Prepared piano has appeared in the works of Brian Eno, Aphex Twin, and even The Velvet Underground, who used paper clips as a preparation in their song “All Tomorrow’s Parties.” In the realm of classical music, the German composer Volker Bertelmann, known more commonly as Hauschka, works with a wide variety of preparations, including ping pong balls, rolls of tape, bottle caps, clothespins, Tic Tacs, tambourines, metal balls and magnets. Some preparations, like the clothespins, are affixed on a particular spot on the desired string, while others, like the tambourine, are laid across the strings of a register spanning an octave or so, creating a delightful rattle.

“I think preparing the piano is a decision for sound as well as an abstraction of the instrument itself,” Haushka told XLR8R in 2014. “In essence, you can add layers that create the sound of an orchestra.”

The sonic qualities imbued by preparation vary from composer to composer—Hauschka’s menagerie of objects create a soundscape that feels as if he is conducting a large and unusual ensemble, rather than sitting at the piano bench, while Moran’s preparations have a trance-like, bell-ringing quality. The effect of preparations also varies from instrument to instrument, as Cage discovered when he began performing his prepared piano compositions in a variety of locales.

“When I first placed objects between piano strings, it was with a desire to possess sounds,” writes Cage. “But, as the music left my home and went from piano to piano and from pianist to pianist, it became clear that not only are two pianists essentially different from one another, but two pianos are not the same either. Instead of the possibility of repetition, we are faced in life with the unique qualities and characteristics of each occasion.”

Beyond Moran and Hauschka, there are few people writing music for prepared piano today, and the legacy of the technique primarily lies with Cage. "[He] was antithetical to academic development of music,” Kuhn says. “He used to say, ‘two people doing the same thing is one too many.’” Far from aping Cage’s work, though, Hauschka and Moran both continue to tread new ground and distinguish themselves as present-day prepared piano composers.

“At first, I was a little intimidated by the idea that if I were to write something for prepared piano, there would immediately be comparisons drawn between me and John Cage,” says Moran. “At a certain point, I felt that I had developed my voice as a composer and felt more comfortable expressing myself and coming at it from my own perspective.”