Samuel Morse’s Reversal of Fortune

It wasn’t until after he failed as an artist that Morse revolutionized communications by inventing the telegraph

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Morse-imaginary-gallery-painting-631.jpg)

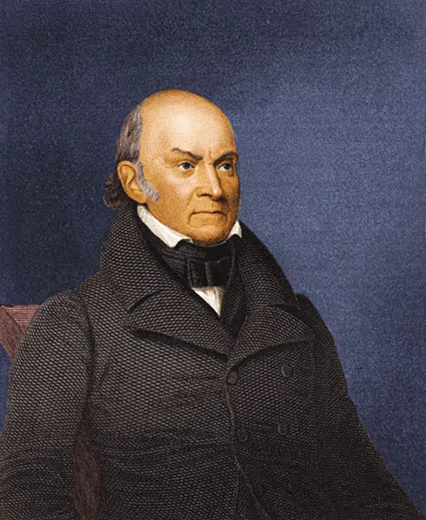

In November 1829, a 38-year-old American artist, Samuel F. B. Morse, set sail on a 3,000-mile, 26-day voyage from New York, bound for Paris. He intended to realize the ambition recorded on his passport: his occupation, Morse stated, was “historical painter.”

Already esteemed as a portraitist, Morse, who had honed his artistic skills since his college years at Yale, had demonstrated an ability to take on large, challenging subjects in 1822, when he completed a 7- by 11-foot canvas depicting the House of Representatives in session, a subject never before attempted. An interlude in Paris, Morse insisted, was crucial: “My education as a painter,” he wrote, “is incomplete without it.”

In Paris, Morse set himself a daunting challenge. By September 1831, visitors to the Louvre observed a curious sight in the high-ceilinged chambers. Perched on a tall, movable scaffold of his own contrivance, Morse was completing preliminary studies, outlining 38 paintings hung at various heights on the museum walls—landscapes, religious subjects and portraits, including Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, as well as works by masters including Titian, Veronese and Rubens.

Working on a 6- by 9-foot canvas, Morse would execute an interior view of a chamber in the Louvre, a space containing his scaled-down survey of works from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Not even the threat of a cholera outbreak slowed his pace.

On October 6, 1832, Morse embarked for New York, his unfinished painting, Gallery of the Louvre, stowed securely below deck. The “splendid and valuable” work, he wrote his brothers, was nearing completion. When Morse unveiled the result of his labors on August 9, 1833, in New York City, however, his hopes for achieving fame and fortune were dashed. The painting commanded only $1,300; he had set the asking price at $2,500.

Today, the newly restored work is on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. through July 8, 2012.

In the six years since Morse had left Paris, he had known seemingly endless struggles and disappointments. He was now 47, his hair turning gray. He remained a widower and still felt the loss of his wife, Lucretia, who had died in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1825, three weeks after the birth of their second son. “You cannot know the depth of the wound that was inflicted when I was deprived of your dear mother,” he wrote to his eldest daughter, Susan, “nor in how many ways that wound has been kept open.” He welcomed the prospect of marrying again, but halfhearted attempts at courtship had come to nothing. Moreover, to his extreme embarrassment, he was living on the edge of poverty.

A new position as professor of art at New York University, secured in 1832, provided some financial help, as well as studio space in the tower of the university’s new building on Washington Square, where Morse worked, slept and ate his meals, carrying in his groceries after dark so no one would suspect the straits he was in. His two boys, meanwhile, were being cared for by his brother Sidney. Susan was in school in New England.

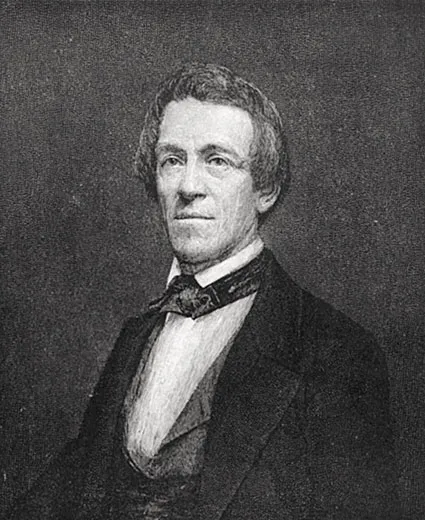

For a long time Morse had hoped to be chosen to paint a historic scene for the Rotunda of the Capitol in Washington. It would be the fulfillment of all his aspirations as a history painter, and would bring him a fee of $10,000. He openly applied for the honor in letters to members of Congress, including Daniel Webster and John Quincy Adams. Four large panels had been set aside in the Rotunda for such works. In 1834, in remarks on the floor of the House he later regretted, Adams had questioned whether American artists were equal to the task. A devoted friend of Morse, and fellow expatriate in Paris during the early 1830s, novelist James Fenimore Cooper, responded to Adams in a letter to the New York Evening Post. Cooper insisted that the new Capitol was destined to be a “historical edifice” and must therefore be a showplace for American art. With the question left unresolved, Morse could only wait and hope.

That same year, 1834, to the dismay of many, Morse had joined in the Nativist movement, the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic outcry sharply on the rise in New York and in much of the country. Like others, he saw the American way of life threatened with ruination by the hordes of immigrant poor from Ireland, Germany and Italy, bringing with them their ignorance and their “Romish” religion. In Morse’s own birthplace, Charlestown, Massachusetts, an angry mob had sacked and burned an Ursuline convent.

Writing under a pen name, “Brutus,” Morse began a series of articles for his brothers’ newspaper, the New York Observer. “The serpent has already commenced his coil about our limbs, and the lethargy of his poison is creeping over us,” he warned darkly. The articles, published as a book, carried the title Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States. Monarchy and Catholicism were inseparable and unacceptable, if democracy was to survive, Morse argued. Asked to run as the Nativist candidate for mayor of New York in 1836, Morse accepted. To friends and admirers he seemed to have departed his senses. An editorial in the New York Commercial Advertiser expressed what many felt:

“Mr. Morse is a scholar and a gentleman—an able man—an accomplished artist—and we should like on ninety-nine accounts to support him. But the hundredth forbids it. Somehow or other he has got warped in his politics.”

On Election Day, he went down to a crushing defeat, last in a field of four.

He kept on with his painting, completing a large, especially beautiful portrait of Susan that received abundant praise. But when word reached Morse from Washington that he had not been chosen to paint one of the historic panels at the Capitol, his world collapsed.

Morse felt sure that John Quincy Adams had done him in. But there is no evidence of this. More likely, Morse himself had inflicted the damage with the unvarnished intolerance of his anti-Catholic newspaper essays and ill-advised dabble in politics.

He “staggered under the blow,” in his words. It was the ultimate defeat of his life as an artist. Sick at heart, he took to bed. Morse was “quite ill,” reported Cooper, greatly concerned. Another of Morse’s friends, Boston publisher Nathaniel Willis,would recall later that Morse told him he was so tired of his life that had he “divine authorization,” he would end it.

Morse gave up painting entirely, relinquishing the whole career he had set his heart on since college days. No one could dissuade him.“Painting has been a smiling mistress to many, but she has been a cruel jilt to me,” he would write bitterly to Cooper. “I did not abandon her, she abandoned me.”

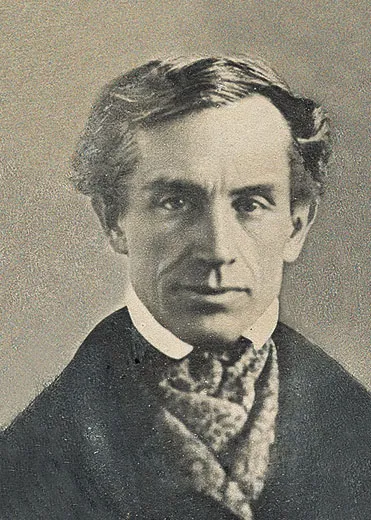

He must attend to one thing at a time, as his father had long ago advised him. The “one thing” henceforth would be his telegraph, the crude apparatus housed in his New York University studio apartment. Later it would be surmised that, had Morse not stopped painting when he did, no successful electromagnetic telegraph would have happened when it did, or at least not a Morse electromagnetic telegraph.

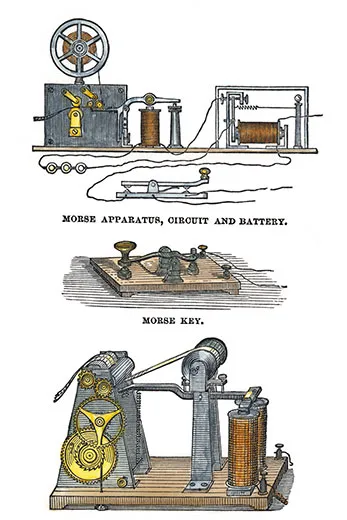

Essential to his idea, as he had set forth earlier in notes written in 1832, were that signals would be sent by the opening and closing of an electrical circuit, that the receiving apparatus would, by electromagnet, record signals as dots and dashes on paper, and that there would be a code whereby the dots and dashes would be translated into numbers and letters.

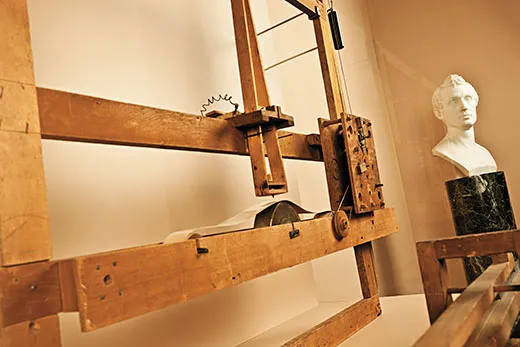

The apparatus he had devised was an almost ludicrous-looking assembly of wooden clock wheels, wooden drums, levers, cranks, paper rolled on cylinders, a triangular wooden pendulum, an electromagnet, a battery, a variety of copper wires and a wooden frame of the kind used to stretch canvas for paintings (and for which he had no more use). The contraption was “so rude,” Morse wrote, so like some child’s wild invention, that he was reluctant to have it seen.

His chief problem was that the magnet had insufficient voltage to send a message more than about 40 feet. But with help from a New York University colleague, a professor of chemistry, Leonard Gale, the obstacle was overcome. By increasing the power of the battery and magnet, Morse and Gale were able to send messages one-third of a mile on electrical wire strung back and forth in Gale’s lecture hall. Morse then devised a system of electromagnetic relays, and this was the key element, in that it put no limit to the distance a message could be sent.

A physician from Boston, Charles Jackson, charged Morse with stealing his idea. Jackson had been a fellow passenger on Morse’s return voyage from France in 1832. He now claimed they had worked together on the ship, and that the telegraph, as he said in a letter to Morse, was their “mutual discovery.” Morse was outraged. Responding to Jackson, as well as to other charges arising from Jackson’s claim, would consume hours upon hours of Morse’s time and play havoc with his nervous system. “I cannot conceive of such infatuation as has possessed this man,” he wrote privately. And for this reason, Cooper and painter Richard Habersham spoke out unequivocally in Morse’s defense, attesting to the fact that he had talked frequently with them of his telegraph in Paris, well before ever sailing for home.

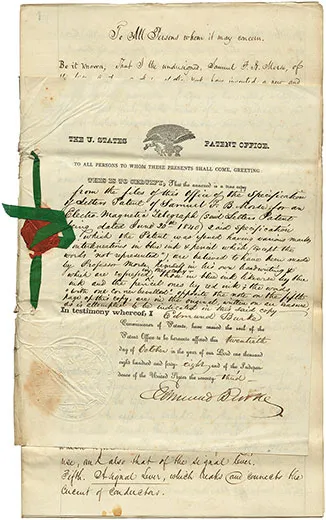

Morse sent a preliminary request for a patent to Henry L. Ellsworth, the nation’s first commissioner of patents, who had been a classmate at Yale, and in 1837, with the country in one of the worst financial depressions to date, Morse took on another partner, young Alfred Vail, who was in a position to invest some of his father’s money. Additional financial help came from Morse’s brothers. Most important, Morse worked out his own system for transmitting the alphabet in dots and dashes, in what was to be known as the Morse code.

In a larger space in which to string their wires, a vacant factory in New Jersey, he and Vail were soon sending messages over a distance of ten miles. Demonstrations were staged successfully elsewhere in New Jersey and in Philadelphia.

There were continuing reports of others at work on a similar invention, both in the United States and abroad, but by mid-February 1838, Morse and Vail were at the Capitol in Washington ready to demonstrate the machine that could “write at a distance.” They set up their apparatus and strung ten miles of wire on big spools around a room reserved for the House Committee on Commerce. For several days, members of the House and Senate crowded into the room to watch “the Professor” put on his show. On February 21, President Martin Van Buren and his cabinet came to see.

The wonder of Morse’s invention was thus established almost overnight in Washington. The Committee on Commerce moved quickly to recommend an appropriation for a 50-mile test of the telegraph.

Yet Morse felt he must have government support in Europe as well, and thus was soon on his way over the Atlantic, only to confront in official London the antithesis of the response at Washington. His request for a British patent was subjected to one aggravating delay after another. When finally, after seven weeks, he was granted a hearing, the request was denied. “The ground of objection,” he reported to Susan, “was not that my invention was not original, and better than others, but that it had been published in England from the American journals, and therefore belonged to the public.”

Paris was to treat him better, up to a point. The response of scientists, scholars, engineers, indeed the whole of academic Paris and the press, was to be expansive and highly flattering. Recognition of the kind he had so long craved for his painting came now in Paris in resounding fashion.

For the sake of economy, Morse had moved from the rue de Rivoli to modest quarters on the rue Neuve des Mathurins, which he shared with a new acquaintance, an American clergyman of equally limited means, Edward Kirk. Morse’s French had never been anything but barely passable, nothing close to what he knew was needed to present his invention before any serious gathering. But Kirk, proficient in French, volunteered to serve as his spokesman and, in addition, tried to rally Morse’s frequently sagging spirits by reminding him of the “great inventors who are generally permitted to starve when living, and are canonized after death.”

They arranged Morse’s apparatus in their cramped quarters and made every Tuesday “levee day” for anyone willing to climb the stairs to witness a demonstration. “I explained the principles and operation of the telegraph,” Kirk would later recall. “The visitors would agree upon a word themselves, which I was not to hear. Then the Professor would receive it at the writing end of the wires, while it devolved upon me to interpret the characters which recorded it at the other end. As I explained the hieroglyphics, the announcement of the word which they saw could have come to me only through the wire, would often create a deep sensation of delighted wonder.” Kirk would regret he had failed to keep notes on what was said. “Yet,” he recalled, “I never heard a remark which indicated that the result obtained by Mr. Morse was not NEW, wonderful, and promising immense practical results.”

In the first week of September, one of the luminaries of French science, the astronomer and physicist Dominique-François-Jean Arago, arrived at the house on the rue Neuve des Mathurins for a private showing. Thoroughly impressed, Arago offered at once to introduce Morse and his invention to the Académie des Sciences at the next meeting, to be held in just six days on September 10. To prepare himself, Morse began jotting down notes on what should be said: “My present instrument is very imperfect in its mechanism, and is only designed to illustrate the principle of my invention....”

The savants of the Académie convened in the great hall of the Institut de France, the magnificent 17th-century landmark on the Left Bank facing the Seine and the Pont des Arts. Just over the river stood the Louvre, where, seven years earlier, Morse the painter had nearly worked himself to death. Now he stood “in the midst of the most celebrated scientific men of the world,” as he wrote to his brother Sidney. There was not a familiar face to be seen, except for Professor Arago and one other, the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, who, in those other days at the Louvre, had come to watch him at his labors.

At Morse’s request, Arago explained to the audience how the invention worked, and what made it different from and superior to other such devices, while Morse stood by to operate the instrument. Everything worked to perfection. “A buzz of admiration and approbation filled the whole hall,” he wrote to Vail, “and the exclamations, ‘Extraordinaire!’ ‘Très bien!’ ‘Très admirable!’ I heard on all sides.”

The event was acclaimed in the Paris and London papers and in the Académie’s own weekly bulletin, the Comptes Rendus. In a long, prescient letter written two days later, the American patent commissioner, Morse’s friend Henry Ellsworth, who happened to be in Paris at the time, said the occasion had shown Morse’s telegraph “transcends all yet made known,” and that clearly “another revolution is at hand.” Ellsworth continued:

“I do not doubt that, within the next ten years, you will see electric power adopted, between all commercial points of magnitude on both sides of the Atlantic, for purposes of correspondence, and men enabled to send their orders or news of events from one point to another with the speed of lightning itself....The extremities of nations will be literally wired together....In the United States, for instance, you may expect to find, at no very distant day, the Executive messages, and the daily votes of each House of Congress, made known at Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Portland—at New Orleans, Cincinnati, etc.—as soon as they can be known in Baltimore, or even the opposite extremity of Pennsylvania Avenue!...Abstract imagination is no longer a match for reality in the race that science has instituted on both sides of the Atlantic.”

That he was in Paris made him feel greater pride than ever, Ellsworth conceded. “In being abroad, among strangers and foreigners, one’s nationality of feeling may be somewhat more excusable than at home.”

Acclaim from the savants and the press was one thing, progress with the French government was another. America’s minister to France, Lewis Cass, provided Morse with a “most flattering” letter of introduction to carry on his rounds, but to no effect. After his eighth or ninth call at the office of the Ministre de l’Intérieur, Morse was still able to speak to no one above the level of a secretary, who asked only that he leave his card. “Every thing moves at a snail’s pace here,” he lamented a full two months after his day of glory at the Académie.

Morse, who had intended at midsummer to stay no more than a month in Paris, was still there at the start of the new year, 1839, and with Kirk’s help, still holding his Tuesday levees at the rue Neuve des Mathurins. That there was no decline in interest in his invention made the delays even more maddening.

It would be at home in America that his invention would have much the best chance, Morse decided. “There is more of the ‘go-ahead’ character with us....Here there are old systems long established to interfere, and at least to make them cautious before adopting a new project, however promising. Their railroad operations are a proof in point.” (Railroad construction in France, later starting than in the United States, was moving ahead at a much slower pace.)

By March, fed up with the French bureaucracy, embarrassed by the months wasted in waiting and by his worsening financial situation, Morse decided it was time to go home. But before leaving, he paid a visit to Monsieur Louis Daguerre, a theatrical scenery painter. “I am told every hour,” wrote Morse with a bit of hyperbole, “that the two great wonders of Paris just now, about which everyone is conversing, are Daguerre’s wonderful results in fixing permanently the image of the camera obscura and Morse’s Electro-Magnetic Telegraph.”

Morse and Daguerre were of about the same age, but where Morse could be somewhat circumspect, Daguerre was bursting with joie de vivre. Neither spoke the other’s language with any proficiency, but they got on at once—two painters who had turned their hands to invention.

The American was amazed by Daguerre’s breakthrough. Years before, Morse had attempted to fix the image produced with a camera obscura, by using paper dipped in a solution of nitrate of silver, but had given up the effort as hopeless. What Daguerre accomplished with his little daguerreotypes was clearly, Morse saw—and reported without delay in a letter to his brothers—“one of the most beautiful discoveries of the age.” In Daguerre’s images, Morse wrote, “The exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it....The effect of the lens upon the picture was in a great degree like that of a telescope in Nature.”

Morse’s account of his visit with Daguerre, published by his brothers in the New York Observer on April 20, 1839, was the first news of the daguerreotype to appear in the United States, picked up by newspapers all over the country. Once Morse arrived in New York, having crossed by steamship for the first time, aboard the Great Western, he wrote to Daguerre to assure him that “throughout the United States your name alone will be associated with the brilliant discovery which justly bears your name.” He also saw to it that Daguerre was made an honorary member of the National Academy, the first honor Daguerre received outside France.

Four years later, in July of 1844, news reached Paris and the rest of Europe that Professor Morse had opened a telegraph line, built with Congressional appropriation, between Washington and Baltimore, and that the telegraph was in full operation between the two cities, a distance of 34 miles. From a committee room at the Capitol, Morse had tapped out a message from the Bible to his partner Alfred Vail in Baltimore: “What hath God wrought?” Afterward others were given a chance to send their own greetings.

A few days later, interest in Morse’s device became greater by far at both ends when the Democratic National Convention being held at Baltimore became deadlocked and hundreds gathered about the telegraph in Washington for instantaneous news from the floor of the convention itself. Martin Van Buren was tied for the nomination with the former minister to France, Lewis Cass. On the eighth ballot, the convention chose a compromise candidate, a little-known former governor of Tennessee, James K. Polk.

In Paris, the English-language newspaper, Galignani’s Messenger, reported that newspapers in Baltimore were now able to provide their readers with the latest information from Washington up to the very hour of going to press. “This is indeed the annihilation of space.”

In 1867, Samuel Morse, internationally renowned as the inventor of the telegraph, returned to Paris once more, to witness the wonders displayed at the Exposition Universelle, the glittering world’s fair. At age 76, Morse was accompanied by his wife Sarah, whom he had married in 1848, and the couple’s four children. So indispensable had the telegraph become to daily life that 50,000 miles of Western Union wire carried more than two million news dispatches annually, including, in 1867, the latest from the Paris exposition.

More than a century later, in 1982, the Terra Foundation for American Art, in Chicago, purchased Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre for $3.25 million, the highest sum paid until then for a work by an American painter.

Historian David McCullough spent four years on both sides of the Atlantic as he researched and wrote The Greater Journey.