How the Santa Fe Railroad Changed America Forever

The golden spike made the newspapers. But another railroad made an even bigger difference to the nation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/de/49deb03d-09a5-4983-8bfa-c34ae46dd554/untitled-1.jpg)

When the railroad tycoon Leland Stanford slammed home the fabled golden spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in May 1869, to join the Central Pacific to the Union Pacific and complete the country’s first transcontinental railroad, the news electrified the country.* A single word dispatched by telegram to the newspapers—“DONE!”—set off brass bands and bell-ringing across the United States. The new venture, the Pacific Railway, was a heroic achievement, but it was hardly an immediate commercial success, in part because it was never really meant to be: President Abraham Lincoln authorized the undertaking back in 1862 primarily to unite East and West in the hope of making a stronger Union once the Civil War was over.

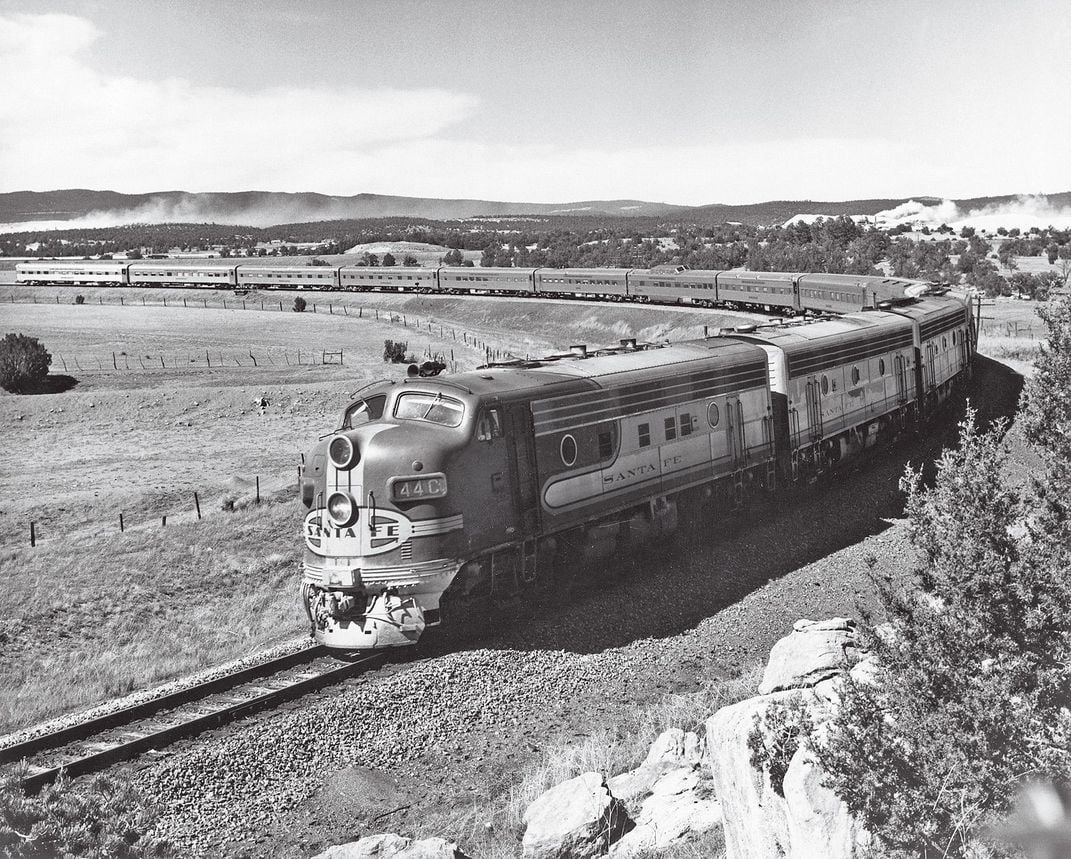

Yet on that score, too, it fell short, leaving the job of unifying the country to the second transcontinental, the Santa Fe, started in Kansas in 1863. Whereas the Pacific Railway relied heavily on federal grants, the Santa Fe raised most of its funds privately. It reached the Pacific in 1887—and helped turn the United States into a single economic powerhouse, linking the industrialized East, the Midwestern heartland and the agricultural glories of the West Coast, all joined in a common market. Still, for some strange reason, the Santa Fe has never received a fraction of the credit that has gone to the Pacific Railway.

Created by an act of Congress, the Pacific Railway proved to be the Apollo program of its day, a massive publicly funded project that existed largely to demonstrate an important point: A railroad could indeed make it to San Francisco.

This was a remarkable accomplishment, but Congress didn’t know what to do with the line once it got there. Promoters paid little attention to building up the freight and passenger traffic needed to succeed financially. Northern congressmen, seeking to retain the benefits of the line for the Union, ensured that it crossed the continent at Chicago’s latitude; the placement exposed the tracks to blizzards that would halt trains for weeks, and sent them through some of the West’s more desolate terrain, well away from the majesty of the Rocky Mountains that might have been attractive to tourists and mining interests alike. In addition, the Pacific initially lacked intersecting “feeder” lines, which would have contributed valuable passengers and freight. And most of the towns that sprang up along the railway were of the “hell-on-wheels” variety, notorious for saloons and bordellos, that flourished only briefly as town-by-town track-laying moved on.

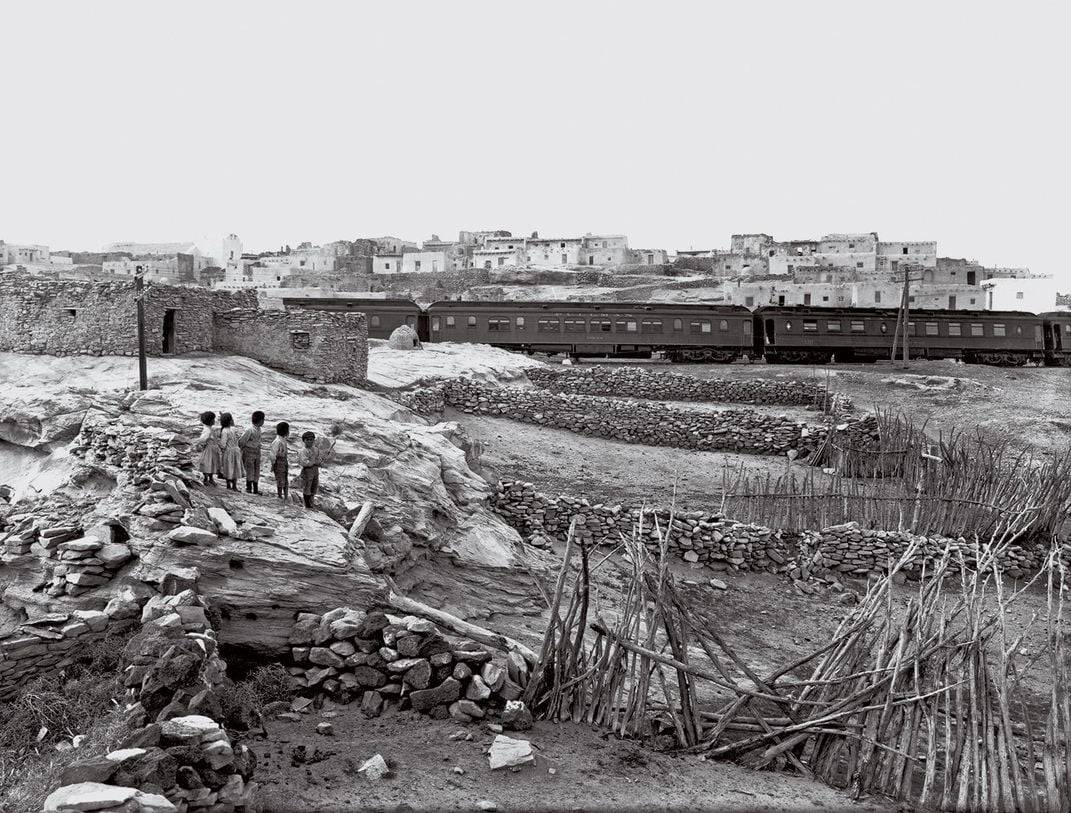

The Santa Fe was different. It tried to choose routes that would generate the traffic to cover construction costs, and it selected sites that were likely to grow after the rail arrived. The company acquired open land at low cost—and then sold it at a nice markup after the rail line enhanced the land’s value. Railroad executives chose the town site, laid out squared-off streets, and often ran their tracks down the middle to create a “right” side (with respectable businesses) and a “wrong” side (with the saloons). It placed its railroad station in the center of town. Unlike the hell-on-wheels towns, Albuquerque and El Paso were built to last.

A corporation in the modern style, the Santa Fe was funded by private investors and run by a professional manager, William Barstow Strong, a veteran railroad man with kindly eyes and an Old Testament beard that ran well down his chest. A big believer in big, he operated by one principle. “A railroad to be successful must also be a progressive institution,” he wrote. By progressive he did not mean politically. “It cannot stand still....If it fails to advance, it must inevitably go backward and lose ground already occupied.” His answer to every business question was to lay down track, and then lay down some more.

The Santa Fe was nonetheless beset by challenges. In the early days, when financing was uncertain, it was slow to lay track across Kansas. When it finally reached Colorado in 1873, the state was still so empty—Denver was the only city of any size, its population roughly 5,000—and much of the terrain still so uncharted, it was hard to know where to place tracks. Worse for the Santa Fe, it came into the state near the tiny trading center of Pueblo, a hundred miles south of Denver.

The leading treatise on this subject in Strong’s day, Arthur Mellen Wellington’s The Economic Theory of the Location of Railways, strongly advised against building any line that didn’t lead to or from a well-populated city. By “well populated,” Wellington meant a New York or Boston, and certainly not Pueblo. Moreover, the Santa Fe did not have Colorado all to itself. A rival company, the Denver and Rio Grande, had started in Denver back in 1872 with the idea of following the Rio Grande River to reach the Pacific in Mexico. It was presided over by a dashing Civil War hero, the Union Gen. William J. Palmer. Over the next decade, Strong and Palmer engaged in a heady game of spy versus spy, tracking each other’s movements, intercepting telegrams and decoding messages, and, at one point, even disguising a surveyor as a Mexican shepherd complete with sheep to make topographical measurements in secret. Each sought to claim not just Colorado, but the entire Southwest out to California, as well as Mexico.

In the course of their competition, they came into direct conflict at a variety of places. In the Royal Gorge outside of Pueblo, they fought perhaps the biggest railroad war in U.S. history, as each man sought exclusive access to one of the richest silver mines in the west, at Leadville. Each side raised an army of ragtag soldiers to scare the other off, and nearly as many lawyers. The war ran two years, and didn’t end until Jay Gould, the godlike robber baron who dominated the railroad industry, personally pressed for a “treaty” that would grant Leadville to the Rio Grande and the open territory to the south to the Santa Fe. With each side bleeding money, and both threatened by Gould’s ability to drive them out of business, they agreed.

That looked like a bitter defeat for the Santa Fe—until the Rio Grande’s silver was soon exhausted, while the land of the Southwest increased in value once it was reached by rail. At the same time Strong was building west from Kansas, he was also building east, reaching Chicago in 1886, making it the westward gateway to the destinations the Santa Fe was adding. The most desirable of these was Los Angeles, which the Santa Fe reached in 1887. As it happened, another line was already in Los Angeles by then: the Southern Pacific, an outgrowth of the earlier Central Pacific, which ran its own line to Chicago through its hub in San Francisco. The Santa Fe’s arrival sparked a frenzied rate competition with the Southern Pacific, each side trying to undercut the other, that ultimately dropped the price of a $125 ticket from Chicago to Los Angeles down to a single, solitary dollar.

Passengers flooded to Los Angeles, boosting the population of the once-sleepy town from roughly 11,000 in 1880 to at least 50,000 by 1890. The speed of this growth set a Los Angeles record that has never been equaled, and dozens of other nearby cities such as Pasadena, San Bernardino and Riverside shot up with it. A brand-new word appeared to capture the real estate explosion—“Boom!”—usually with exclamation mark attached.

The Santa Fe’s arrival created Southern California as a coveted destination for Easterners and Midwesterners, and marked the culmination of the famous injunction to “Go west!” Fevered promoters marketed greater Los Angeles as paradise, and it pretty much was: a place of eternal sunshine, studded with exotic palm trees and bright with roses year-round. It was an Eden from which navel oranges could be shipped in the Santa Fe’s ventilated or refrigerated boxcars to delight Americans everywhere. “The Santa Fe made Southern California,” says Richard White, a railroad historian. “And Southern California made the Santa Fe.”

The railroad’s success had other consequences. It helped to double Chicago’s population in the 1880s, making it the nation’s lumberyard and stockyard in the process. Chicago’s central location inspired a sales innovation, the Montgomery Ward & Co. mail-order catalog, founded in 1872, which delivered by train goods from anywhere directly to customers everywhere, skipping retail stores and allowing Americans to get in on the latest big-city fashions. After the Santa Fe arrived in Chicago, the catalog fattened up to more than 240 pages, offering an astounding 10,000 items.

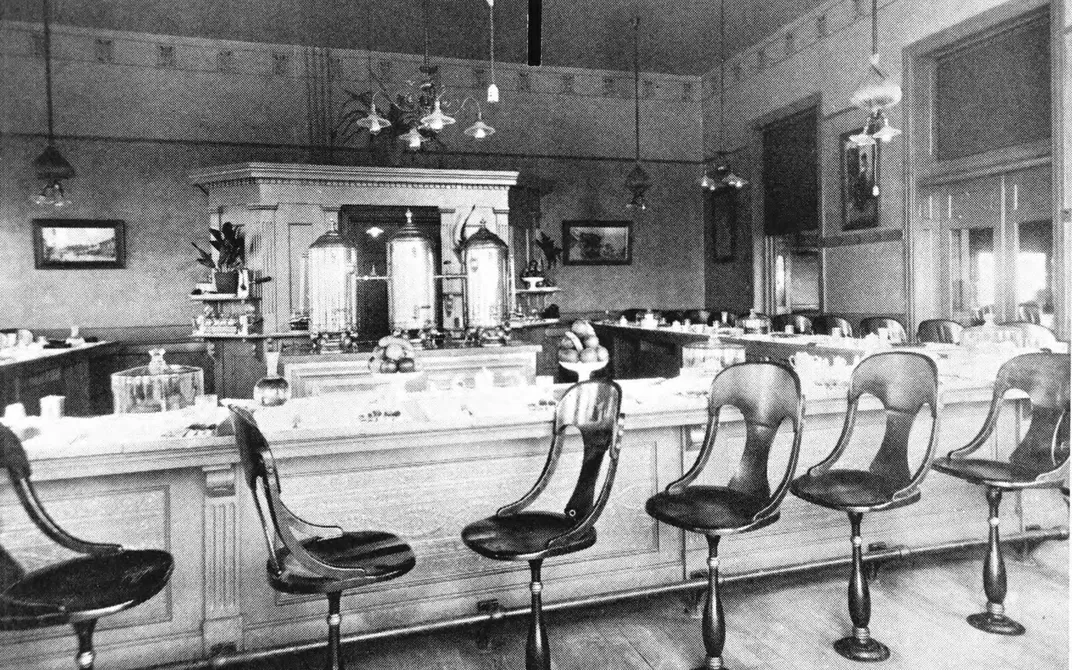

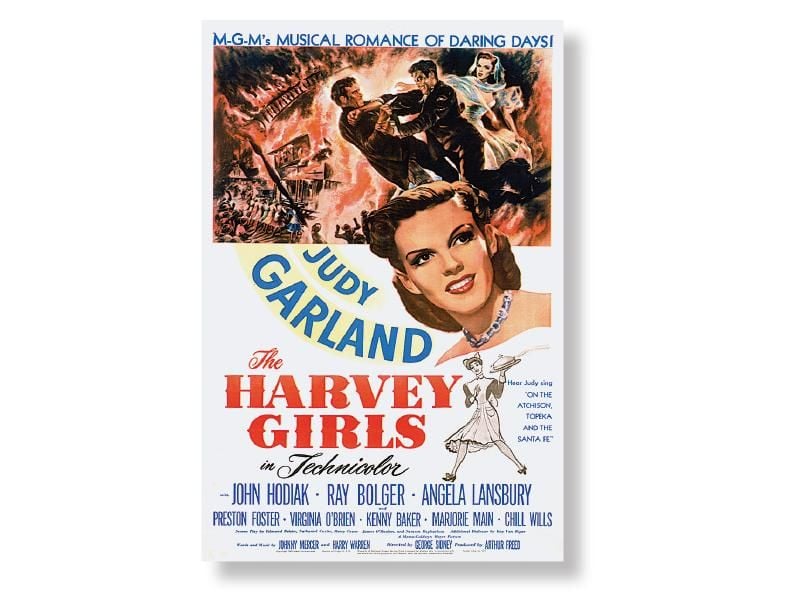

With the line at full steam between two burgeoning cities, the Santa Fe gave rise to another innovation that would become a fixture of the American landscape: the chain restaurant. In partnership with New York restaurateur Fred Harvey, high-end Harvey House eateries appeared every hundred miles wherever the Santa Fe ran, serving a million meals a month early in the next century.

The Santa Fe played a seminal role in the success of the movie business, itself a force that shaped the national character. After a New Jersey filmmaker, David Horsley, arrived in Hollywood to make westerns in the year-round sunshine early in the new century, D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille followed, making Los Angeles the dream factory for the nation.

As for Strong himself, the real dreammaker, he was forced to resign from the Santa Fe in 1889—his ambitious track-laying had outpaced the company’s revenues. Although raised in the Midwest, Strong retired in Los Angeles, settling in a modest bungalow. In declining health, he died there on August 3, 1914, at age 77. His obituary in the Los Angeles Times mentioned little about Strong’s railroad career, noting instead that he had a “forceful handshake” that suggested a “gratuitous humanity.”

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels

Nearly all were sent to prison or killed. But not before they pulled off some of the biggest train robberies ever

By Teddy Brokaw

The Great Rondout Train Robbery • 1924

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/28/662850f1-c965-4c23-8806-f6551286f394/ss3.jpg)

Roy Gardner's Roseville Robbery • 1921

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/fc/21fcdcca-db77-4d8b-a5ac-737f1b522f32/ss4.jpg)

Mineral Range Railroad Robbery • 1893

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/df/cadfbd1e-73fb-4577-b298-024250b9071e/ss1.jpg)

Hudson River Railroad Robbery • 1869

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/ed/b6ed8300-19d7-4d56-952f-c82d97cf381c/ss2.jpg)

The Reno Gang's Adams Express • 1868

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/af/6caf4c79-9436-42ec-b14e-5043cea69693/ss5.jpg)

*Editor's Note, June 30, 2021: This article initially said that the golden spike joining the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads was driven home in Promontory Point, Utah. In fact, the railroads were joined in Promontory Summit, Utah.