Santa’s Trusty Robot Reindeer

A special visit from the Ghost of Christmas Retro-Future

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201112231031051981-tomorrows-home-sm-web.jpg)

When I was a kid I would’ve given just about anything to see a hoverboard under the family Christmas tree. Back to the Future II came out in 1989 (when I was six years old) and the movie promised kids like me a world of hoverboards and ubiquitous product placement by the year 2015. I even occasionally get emails from people who ask if hoverboards are real. These people vaguely remember seeing a short promotional documentary when they were kids about the making of BTTF2, which included a joke about hoverboards from director Robert Zemeckis. With a smirk that was obviously too subtle for the kiddies, Zemeckis claimed that hoverboards were real, but that child safety groups wouldn’t let them be released into stores. I’ve broken many a dear reader’s heart by sending out that link.

Alas, hoverboards still aren’t real (at least not in the way that BTTF2 envisioned them) and I never saw one under our Christmas tree. But the latter half of the 20th century still saw plenty of predictions for the Christmas celebrations of the future — everything from what kind of technologically advanced presents would be under the tree, to how visions of Santa Claus may evolve.

The 1981 book Tomorrow’s Home by Neil Ardley includes a two page spread about the Christmas presents and celebrations of the future. If we ignore the robot arm serving Christmas treats, Ardley pretty accurately describes the rise of user-generated media, explaining the ways in which the household computer will allow people to manipulate their video and musical creations:

Christmas in the future is an exciting occasion. Here the children have been given a home music and video system that links into the home computer. They are eagerly trying it out. The eldest boy is using the video camera to record pictures of the family, which are showing on the computer viewscreen. However, someone else is playing with the computer controls and changing the images for fun. At the same time, another child is working at the music synthesizer, creating some music to go with the crazy pictures.

But what of my parents’ generation, the Baby Boomers? What were they told as children about the Christmases to come? Below we have a sampling of predictions from the 1960s and 70s about what the Christmas festivities of the future would look like. Some of these predictions were made by kids themselves — people who are now in their 50s and 60s.

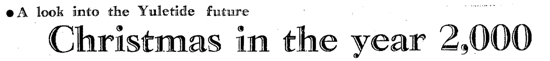

Headline from the November 28, 1967 Gleaner

The November 28, 1967 issue of the Kingston, Jamaica newspaper The Gleaner ran a story by Londoner Carole Williams imagining what Christmas of the year 2000 would look like. It’s interesting that Williams spends the first paragraph acknowledging that the year 2000 could very well be a nightmarish, Orwellian dystopia wherein Santa lies dead in a snowbank:

Christmas in the Big Brother world of George Orwell did not exist at all; Santa Claus was dead. Indeed, he had never lived. Many eminent sociologists are today profoundly pessimistic at a rate of social progress which is carrying mankind swiftly, it seems, towards Big Brother living.

But to take the optimistic view that Christmas 2000 will be just as much a Christian celebration as now leads to interesting speculation. Firstly, Christmas Day 2000 will be the greatest festival ever known simply because of the anniversary. The events of Christmas 1000 will no doubt be recreated with techniques to envisage now, as a centre-piece of global festivity.

Williams continues to describe a jolly world that is connected by a vast network of videophones:

On Christmas Day 2000, greetings will be sent around the world in colour by television, person to person, as simply as a telegram. There will be two TV systems in every home: one for news and entertainment, the other for personal use, linked to telephone networks. Thus Mr Smith in Hong Kong will dial his home in London from his hotel room, say Happy Christmas and watch his children open their presents.

What will be in those bright, bulky packages only Father knows, but he will have had a staggering variety of gifts to choose from. More popular than today, probably, will be travel vouchers — tickets for supersonic weekend tours of, say, Kenya, or Brazil — anywhere where wild animals and vegetation are still free and unchecked. A ticket to Tokyo from London will cost about 100 dollars in the new world currency. 100 dollars will represent perhaps one week’s pay for a medium-grade computer operator.

Very young children will find midget colour TV sets, no larger than today’s transistor radios, in their Christmas stockings, and tiny wire recorders. Toys will probably be of the do-it-yourself variety — building go-karts powered by selenium cells, with kits for making simple computer and personal radars (of the type chests will use in Blind Man’s Buff). Teenagers will get jet-bikes, two seater hovercraft and electronic organs, the size of a small desk, that will compose pop tunes as well as play them.

The piece also explains that the most glorious Christmas celebration won’t even occur on the earth. Remember that this was 1967, two years before humans would set foot on the moon.

The most extraordinary Christmas in the year 2000 will without a doubt be the one spent by a group of men on the moon — scientists and astronauts of maybe several nations carried there in American and Russian rockets, establishing the possibility of using the moon as a launch-pad for further exploration.

They will be digging for minerals, looking at planets and earth through electronic telescopes so high-powered that they will be able to pick out the village of Bethlehem. Their Christmas dinner will be from tubes and pill bottles, and it is extremely unlikely that any alcohol at all will be allowed — or an after-dinner cigar.

Williams explains that the religious festivities surrounding Christmas will likely be the same as they were in 1967, but the buildings of worship will be different:

Down on earth, religious celebrations will continue as the have done for the previous two thousand years, but in many cities the churches themselves will have changed; their new buildings will be of strange shapes and design, more functional perhaps than inspirational and hundreds of them will be interdenominational, a practising symbol of ecumenicalism.

Illustration of a robot Santa Claus by Will Pierce (2011)

The Dec 23, 1976 Frederick News (Frederick, MD) looked a little deeper into the future and described Christmas in the year 2176.

Just imagine what Christmas would be like 200 years from now: An electronic Santa Claus would come down the chimney because everyone is bionic and Santa Claus should be, too. Christmas dinner may consist of sea weed and other delicacies from the deep. Mistletoe would only be placed in aristocratic homes because it would be much too expensive for the average family to buy.

There would be no such thing as Christmas shopping, because all the ordering can be done from home by an automatic shopping device.

Children would no longer have to wait so impatiently for the Christmas holiday to officially close schools, because you would only have to unplug the electronic classroom connector each student would have in his home. There would be no worry of what to do with the Christmas tree after the season, because it would have to be replanted and used again the following year.

The Lethbridge Public Library in Canada held a Christmas short story contest in 1977. The winners were published in December 24 edition of The Lethbridge Herald. Little Mike Laycock won first prize in the 9-10 year old category with his story titled, “Christmas in the Future.”

It was the night before Christmas, in the year 2011, and in a castle far away, a man named Claus was scurrying down a gigantic aisle of toys. Now and then he stopped in front of an elf to give him directions.

“Hurrying, hurrying,” he mumbled, “will I ever get some rest?” Finally everything was ready and the elves began to load the sled. Rudolph and all the other reindeer had grown long beards, and were too old to pull the sled anymore. So Santa went out and bought an atomic powered sled. It was a smart idea because in the winter nothing runs like a (John) Deere.

Well, if you could have seen the pile of toys you would have been amazed! There were piles of toys fifteen feet tall! Soon all the toys were loaded. Santa put on his crash helmet, hopped into the sled and brought the cockpit cover down. He flicked a few switches, pressed a few buttons, and he was off. Zooming through the air at sublight speed, he delivered toys to places like China, U.S.S.R., Canada, U.S.A. etc.

He flew over the cities dropping presents. He dropped them because each present had a small guidance system that guided the presents down a chimney. Then parachutes opened and the presents gently touched the ground.

It was snowing heavily and the ground was glittering with beauty. The stars were shining, the moon was full, and there, painted against the sky, was Santa, zooming across the sky in his atomic powered sled.

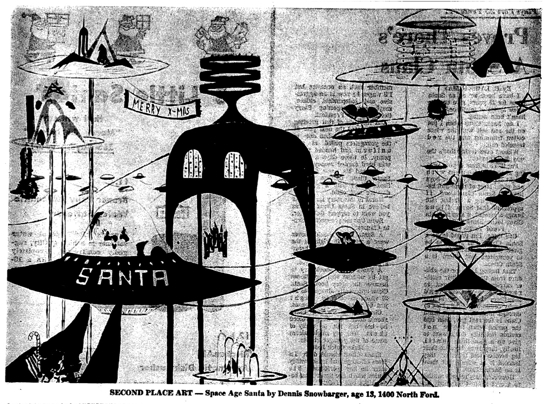

This drawing by 13-year-old Dennis Snowbarger appeared in the November 28, 1963 Hutchinson News (Hutchinson, Kansas). Dennis won second place in a contest the newspaper put on. It would appear that Dennis’s art was inspired by the TV show The Jetsons, whose original 24 episode run was from late 1962 through early 1963.

"Space Age Santa" by 13-year-old Dennis Snowbarger in the November 28, 1963 Hutchinson News

The “Junior Edition” of the San Mateo Times (San Mateo, CA) was promoted as being “by children, for everyone.” In the December 17, 1966 edition of the Junior Edition, Bill Neill from Abbott Middle School wrote a short piece which imagined a “modern Santa Claus” in the year 2001. In Bill’s vision of Christmas future, not only does Santa have an atomic-powered sleigh, he also has robot reindeer!

It is the year 2001. It is nearing Christmas. Santa and all his helpers were making toy machine guns, mini jets (used like a bike), life-size dolls that walk, talk and think like any human, electric guitars, and 15-piece drum sets (which are almost out of style).

When the big night arrives, everyone is excited. As Santa takes off, he puts on his sunglasses to protect his eyes from the city lights. Five, four, three, two, one, Blast Off! Santa takes off in his atomic-powered sleigh and his robot reindeer.

Our modern Santa arrives at his first house with a soft landing. After Santa packs up his portable chimney elevator, fire extinguisher and gifts, he slides down the chimney. These motions are repeated several billion times.

Things have changed. The details of how Santa arrives has changed and will continue to change, but his legend will remain.

Original illustration of robot Santa by Will Pierce.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)