Savoring Pie Town

Sixty-five years after Russell Lee photographed New Mexico homesteaders coping with the Depression, a Lee admirer visits the town for a fresh slice of life

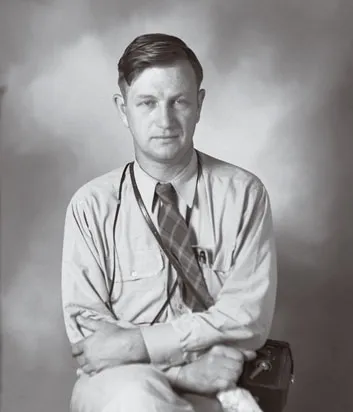

The name alone would make a stomach-growling man wish to get up and go there: PieTown. And then too, there are the old photographs—those moving gelatin-silver prints, and the equally beautiful ones made in Kodachrome color, six and a half decades ago, at the heel of the Depression, on the eve of a global war, by a gifted, itinerant, government, documentary photographer working on behalf of FDR’s New Deal. His name was Russell Lee. His Pie Town images—and there are something like 600 of them preserved in the archives of the Library of Congress—portrayed this little clot of high-mountain-desert New Mexico humanity in all of its redemptive, communal, hard-won glory. Many were published last year in Bound for Glory, Americain Color 1939-43. But let’s get back to pie for a minute.

“Is there a particular kind you like?” Peggy Rawl, coowner of PieTown’s Daily Pie Café, had asked sweetly on the phone, when I was still two-thirds of a continent away. There was clatter and much talk in the background. I’d forgotten about the time difference between the East Coast and the Southwest and had called at an inopportune hour: lunchtime on a Saturday. But the chief confectioner was willing to take time out to ask what my favorite pie was so that she could have one ready when I got there.

Having known about PieTown for many years, I was itching to go. You’ll find it on most maps, in west-central New Mexico, in CatronCounty. The way you get there is via U.S. 60. There’s almost no other way, unless you own a helicopter. Back when Russell Lee of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) went to Pie Town, U.S. 60—nowhere near as celebrated a highway as its more northerly New Mexico neighbor, Route 66, on which you got your kicks—called itself the “ocean to ocean” highway. Big stretches weren’t even paved. Late last summer, when I made the trek, the road was paved just fine, but it was still an extremely lonesome two lane ribbon of asphalt. We’ve long licked the idea of distance and remoteness in America, and yet there remain places and roads like PieTown and U.S. 60. They sit yet back beyond the moon, or at least they feel that way, and this, too, explains part of their beckoning.

When I saw my first road sign for PieTown outside a New Mexico town called Socorro (by New Mexico standards, Socorro would count as a city), I found myself getting cranky and strangely elevated. This was because I knew I still had more than an hour to go. It was the psychic power of pie, apparently. Again, I hadn’t planned things quite right—I’d left civilization, which is to say Albuquerque—without properly filling my stomach for the three-hour haul. I was muttering things like, They better damn well have some pie left when I get there. The billboard at Socorro, in bold letters, proclaimed: HOME COOKING ON THE GREAT DIVIDE. PIE TOWNUSA. I drove on with some real resolve.

Continental Divide: this is another aspect of PieTown’s strange gravitational pull, or so I have become convinced. People want to go see it, taste it, at least in part, because it sits right on the Continental Divide, at just under 8,000 feet. PieTown, on the Great Divide—it sounds like a Woody Guthrie lyric. Something there is in our atavistic frontier self that hankers to stand on a spot in America, an invisible demarcation line, where the waters start to run in different directions toward different oceans. Never mind that you’re never going to see much flowing water in PieTown. Water, or, more accurately, its lack, has much to do with PieTown’s history.

The place was built up, principally, by Dust Bowlers of the mid- and late 1930s. They were refugees from their busted dreams in Oklahoma and West Texas. A little cooperative, Thoreauvian dream of self-reliance flowered 70 and 80 years ago, on this red earth, amid these ponderosa pines and junipers and piñon and rattlesnakes. The town had been around as a settlement since at least the early 1920s, started, or so the legend goes, by a man named Norman who’d filed a mining claim and opened a general store and enjoyed baking pies, rolling his own dough, making them from scratch. He’d serve them to family and travelers. Mr. Norman’s pies were such a hit that everybody began calling the crossroads PieTown. Around 1927, the locals petitioned for a post office. The authorities were said to have wanted a more conventional name. The Pie Towners said it would be PieTown or no town.

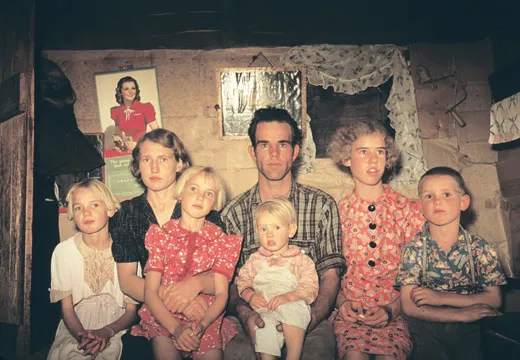

In the mid-’30s, something like 250 families lived in the surrounding area, most of them in exile from native ground gone arid. By the time Russell Lee arrived, in the company of his wife, Jean, and with a trunk full of cameras and a suitcase full of flashbulbs, the town with the arresting name boasted a Farm Bureau building, a hardware and feed store, a café and curio shop, a hotel, a baseball team, an elementary school, a taxidermy business. There was a real Main Street that looked a little like a movie set out of the Old West. Daily, except Sunday, the stagecoach came through, operated by Santa Fe Trail Stages, with a uniformed driver and with the passengers’ luggage roped to the roof of a big sedan or woody station wagon.

Lee came to PieTown as part of an FSA project to document how the Depression had ravaged rural America. Or as the Magdalena News put it in its issue of June 6, 1940: “Mr. Lee of Dallas, Texas, is staying in Pietown, taking pictures of most anything he can find. Mr. Lee is a photographer for the United States department of agriculture. Most of the farmers are planting beans this week.”

Were Lee’s photographs propagandistic, serving the aims of an administration back in Washington bent on getting New Deal relief legislation through Congress and accepted by the American people? Of course. That was part and parcel of the mission of the FSA/OWI documentary project in the first place. (OWI stands for Office of War Information: by the early ’40s, the focus of the work had shifted from a recovering rural America to an entire nation girding for war.) But with good reason, many of the project’s images, like the names of some of those who produced them—Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, Marion Post Wolcott, John Vachon, Gordon Parks, Russell Lee—have entered American cultural myth. The results of their collaborative work—approximately 164,000 FSA/OWI prints and negatives—are there in drawer after drawer of file cabinets at the Library of Congress in a room I have visited many times. (Most of the pictures are now also on-line at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsowhome.html.) Taken together, those images have helped define who we are as a people, or who we’d like to think we are; they amount to a kind of Movietone newsreel looping through our heads.

Lee took plenty of pictures in PieTown of the deprived living conditions; he showed how hard it all was. His pictures weren’t telling lies. And yet his pictures of people like the Caudills almost made you forget the deprived living conditions, forgive them, because the sense of the other—the shared food and good times at all-day community church sings—was so powerfully rendered. In front of Lee’s camera, the Caudills’ lives seemed to narrate the received American story of pluck and determination.

Never mind that I now also knew—in the so-called more rational and objective part of my brain—that the Thoreauvian ideal of self-reliance had foundered badly in this family. For Doris and Faro Caudill (and their daughter, Josie, who was about 8 when Lee took his pictures), the PieTown dream became closer to a nightmare. Faro got sick, got lung trouble, the family moved away (just two years after the pictures were taken). Faro sought work in the city, Faro ran around. An acrimonious divorce ensued. Doris ended up married to another man for 39 years. She even went to Alaska to try the American homesteading dream all over again. There is a beautiful book published several years ago about the Caudills and their saga, but especially about Doris: Pie Town Woman, by Joan Myers, a New Mexico author.

In 1942, when Faro Caudill hitched the gate at his PieTown homestead for the last time, he scrawled on the wood: “Farewell, old homestead. I bid you adieu. I may go to hell but I’ll never come back to you.”

And yet what you also get from Myers’ book about Doris in her very old age, not long from her death, is a deep longing to be there again, to have that life again. She told the author she’d like to have hot and cold running water, though. “As old as I am, I like to take a bath now and then. We would take a bath on Saturday night. We had a number three bathtub. I’d get the water all hot and then I’d bathe Josie and then I’d take a bath and then Faro would take a bath. . . . You kind of wore the water out.”

What happened in this dot of civilization, to go on with PieTown’s history, is that the agricultural dream dried up—quite literally. The good growing years lasted not even a generation. It was the water once more, a grapes of wrath anew, the old Western saga of boom to bust. Somehow, by the ’50s, the climate had seemed mysteriously to shift, just as it had in the places abandoned earlier by those Okies and West Texans and Kansans. The winters became balmier. The snows wouldn’t fall, not like they once did; the earth refused to hold its moisture for the spring planting. The corn and pinto bean fields, which two decades before had yielded rich harvests, as long as its tillers were willing to give to them the sunup-to-sundown work that they demanded, withered. And so, many of those once-exiled families found themselves exiled again. Some of them had already long moved on to cities, to jobs in defense plants and airplane factories. They’d gone to Albuquerque, to California, where the life was said to be easier, the paychecks regular.

But the town never died out entirely. Those who’d stayed behind made a living by any means they could: drilling wells, grazing cows, running mom and pop businesses, opening cafés called the Pie-O-Neer, recently reopened, or the Break 21. And new homesteaders always seemed to arrive, willing to try out the PieTown dream.

The highway had already taken me through and around the parched mountains and mesas and across a vast moonlike tract from the Pleistocene age called the Plains of San Agustin. The land had begun to rise again, almost imperceptibly at first, and then rather dramatically. It was still desert, but the land looked more fertile now. That was mostly illusion.

I couldn’t find any town at first. The “town” looked like no more than a wide spot in the road, with the Daily Pie Café and the post office and an art gallery just about the only visible enterprises. I just had to adjust my eyes, I just had to give it time—to find the drilling business, the realty office selling ranchettes, the mobile home campgrounds, the community center, the several churches, the fist of simple homes that stood along the old main street before they relocated U.S. 60, the long-closed old log hotel still standing on the old U.S. 60, home now to bats and spiders and snakes. Russ and Jean Lee had lodged there while he’d made his pictures.

I just had to look around to find the town cemetery—windblown, weedy, ghostly, beautiful. There were graves piled with stones, and under them were Americans who had lasted 90 and more years.

I walked into the offices of the Alegres Electric Company, a husband and wife operation owned by Judy and Bob Myers. They are both licensed electricians. The shop was in a little mud-dried house with a brown tin corrugated roof across the macadam from the Daily Pie. In addition to their electrical business, the Myers were also offering trail mix and soft drinks and flashlight batteries. “Hikers come through on the Divide,” Judy explained. She was sitting at a computer, a classic-looking frontier woman with deep facial lines set in a leathery tan. She said that she and her husband had chased construction jobs all over the country, and had somehow managed to raise their kids while doing it. They’d found PieTown four or five years ago. They intended to stick. “As long as we can keep earning some kind of living here,” Judy said. “As long as our health would hold.” Of course, there are no doctors or hospitals nearby. “I guess you could call us homesteaders,” Judy said.

I encountered Brad Beauchamp. He’s a sculptor. He had topped 60. He was staffing the town Tourist and VisitorInformationCenter. There was a sign with those words in yellow lettering on the side of an art gallery. There was a big arrow and it directed me to the rear of the gallery. Beauchamp, instantly friendly, ten years a Pie Towner, is a transplant from San Diego, as is his wife. In California, they’d had a horse farm. They wanted a simpler life. Now they owned 90 acres and a cabin and an array of four-footed animals. They were making their living as best they could. Beauchamp, a lanky drink of water recovering from a bicycling accident, talked of yoga, of meditation, of a million stars in the New Mexico sky. “I’ve worked real hard on . . . being calm out here,” he said.

“So are you calmer?”

“I’ve got such a long way to go. You know, when you come to a place like this, you bring all your old stuff with you. But this is the place. We’re not moving.”

Since the sculptor was staffing the visitor’s center, it seemed reasonable to ask if I could get some PieTown literature.

“Nope,” he said, breaking up. “That’s because we don’t have any. We have a visitor information center, but nothing about PieTown. We do have brochures for a lot of places in the state, if you’d like some.”

Outside the post office, on the community bulletin board, there was a hand-scrawled notice: “Needed. Support from Community for Pie Festival. 1) Organize a fiddle contest. 2) Help set up on Friday 10 Sept.” The planners of the all-day event were asking for volunteers for the big pie-eating contest. Judges were needed, cleanup committees. There would be the election of a Pie queen and king. Candidates for the title were being sought. Sixty-four years before, photographer Lee had written to his boss Roy Stryker in Washington: “Next Sunday at Pietown they are having a big community sing—with food and drink as well—it lasts all day so I’m going to be sure to be here for that.” Earlier Stryker had written to Lee about PieTown: “[Your] photographs, as far as possible, will have to indicate something of what you suggest in your letter, namely: an attempt to integrate their lives on this type of land in such a way as to stay off the highways and the relief rolls.”

There had been no passage of years. It was as if the new stories were the old stories, just with new masks and plot twists.

And then there was the Daily Pie. I’ve been to some restaurants where a lot of desserts were listed on the menu, but this was ridiculous. The day’s offerings were scrawled in a felt-tip pen on a big “Pie Chart” above my head. In addition to regular apple, there was New Mexican apple (laced with green chili and piñon nuts), peach walnut crumb, boysen berry (that’s the spelling in Pie Town), key lime cheesecake (in Pie Town it’s a pie), strawberry rhubarb, peanut butter (it’s a pie), chocolate chunk crème, chocolate walnut, apple cranberry crumb, triple berry, cherry streusel, and two or three others that I can no longer remember and didn’t write down in my notebook. The Pie Chart changes daily at the Daily Pie, and sometimes several times within a day. A red dot beside a name meant that there was at least a whole other pie of that same kind back in the kitchen. And a 1 or a 2 beside a name meant there were just one or two slices left, and apparently wouldn’t be any more until that variety came up in the cycle again.

I settled on a piece of New Mexican apple, which was a lot better than “tasty.” It was zingy. And now that I’ve sampled my share of PieTown’s finest selections, I’d like to relay a happy fact, which is probably implicit anyway: at the Daily Pie Café—where so much of PieTown’s current life unfolds— they serve much more than pie. Six days a week they make a killer breakfast and a huge lunch, and two days a week they dish until 8 p.m., and on Sundays, the pièce de résistance, they’re glad to work you over with one of those all-afternoon, old-fashioned turkey, ham or roast-beef dinners with potatoes and three vegetables that your grandmother used to make, the kind that got sealed lovingly in family albums and in the amber of memory.

For three days I took my meals at the Daily Pie, and as it happened, I became friendly with an old-timer named Paul Painter. He lives 24 miles from PieTown, off the main road. Six days a week—every day that it’s open—Painter comes in his pickup, 48 miles round trip, most of it by dirt road, arriving at the same hour, 11 a.m. “He’s steady as a damn stream coming out of the mountain,” said Mike Rawl, husband of Daily Pie Café pie chef Peggy Rawl, not to mention the café’s greeter, manager, shopper, cook and other co-owner. Every day Painter puts in the same order: big steak (either rib-eye or New York strip), three eggs, toast and potatoes. He’ll take two hours to dine. He’ll read the paper. He’ll flirt with the waitresses. And then he’ll drive home. Painter is deep in his 70s. His wife died years ago, his kids live away. He told me that he spends every day and night alone, except for those several hours at the café. “Only way I know what day of the week it is, is from a little calendar I keep right by the light bulb in my bedroom,” he said. “Every night I reach over and make a check. And then I turn out the light.”

Said Rawl one day in his café, after the rush of customers: “I’ve thought about it a lot. I think the very same impulses that brought the homesteaders out here brought us out. My family. They had the Dust Bowl. Here you’ve got to come out and buy a tax license and deal with insurance and government regulations. But it’s the same thing. It’s about freedom, the freedom to leave one place and try to make it in another. For them their farms got buried in sand. They had to leave. Back in Maryland it never really seemed like it was for us. And I don’t mean for us, exactly. You’re helping people out. This place becomes part of the town. I’ve had people running out of gas in the middle of the night. (I’ve got a tank out back here.) You’re a part of something. That’s what I mean to say. It’s very hard. You have to fight it. But the life here is worth the fight.”

I went around with “Pop” McKee. His real name is Kenneth Earl McKee. He has a mountain man’s untrimmed white beard. When I met him, his pants were held up by a length of blue cord, and the leather of his work boots seemed soft as lanolin. He had a little heh-heh caving-in-on-itself laugh. He has piercing blue eyes. He lives in a simple home not even 200 yards from where, in the early summer of 1940, a documentarian froze time in a box on a pine board elementary school stage.

Pop McKee, past 70, is one of the last surviving links to Russell Lee’s photographs. He is in many of Russell Lee’s PieTown photographs. He is that little kid, third from right, in the overalls at the PieTown community school, along with his cousin and one of his sisters. The kids of PieTown are singing on a makeshift stage. Pop is about 8.

In 1937, Pop McKee’s father—Roy McKee, who lies in the town cemetery, along with his wife, Maudie Bell—had driven a John Deere tractor from O’Donnell, Texas, toward his new farming dream, pulling a wagon with most of the family possessions. It took him about five days. Pop asked me if I wanted to go out to the old homestead. I sure did. “I guess we will then,” he said, cackling.

“Life must have been so hard,” I said, as we drove to the homestead. It was out of town a little ways.

“Yeah, but you didn’t know it,” he said.

“You never wanted a better life, an easier one?”

“Well, you didn’t know no better one. A fellow doesn’t know a better one, he won’t want one.”

At the homeplace, a swing made from an old car seat was on the porch. It was a log house chinked with mortar. Inside, the dinnerware was still in a beautiful glass cabinet. There were canned goods on a shelf. No one lived at the homeplace, but the homeplace still somehow lived.

“He had cows when he died,” Pop said of his dad, who made 90 in this life.

“Did you tend him at the end?”

“He tended himself. He died right over there, in that bed.”

All of the family was present that day, May 9, 2000. Roy McKee, having come out to PieTown so long ago, had pulled each grown child down to his face. He said something to each one. And then turned to the wall and died.