Scattered Actions: October 1861

While the generals on both sides deliberated, troops in blue and gray fidgeted

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-Death-Edward-Baker-631.jpg)

As the nation was remaking itself politically, it was doing so technologically as well. The new Union Army Balloon Corps began building a fleet and hiring aeronauts to survey enemy movements from the air. Reconnaissance balloons would enable Union regiments to fire artillery accurately, even while unable to see the enemy from the ground.

Western Union completed its transcontinental telegraph system that October 150 years ago, allowing telegrams to be sent coast to coast for the first time. Within days, the 18-month-old Pony Express, which had sped messages from Missouri to California and back (it delivered Lincoln’s first inaugural address in just under eight days), was officially shuttered.

The month saw only scattered military action as generals on both sides deliberated their next move. An 8th Illinois Infantry private complained in his diary: “If they keep us this way much longer we will be tender as women.” Not that women were so tender; the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child wrote in a letter that “this imbecile, pro-slavery government does try me so, that it seems as if I must shoot somebody.”

On October 12, several Confederate ships, led by a metal-sheathed ram, attacked five Union vessels off the coast of New Orleans, running two of them aground. The victory cheered New Orleans residents, including Clara Solomon, a 16-year-old girl who wrote in her diary the next day: “Thus have the insolent blockaders and invaders received another most signal rebuke for their insane attempt to subjugate this free and indomitable people.”

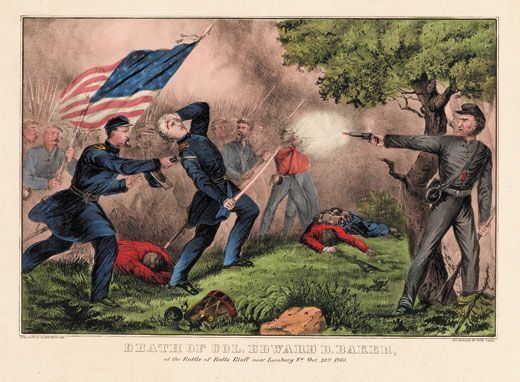

A greater defeat awaited Union forces on the 21st. At Ball’s Bluff on the Potomac River, Union Col. Edward D. Baker, a friend of the president’s, led his soldiers in a charge up the cliff, only to be pushed back into the river, incurring 921 casualties, including himself, out of 1,700. (Confederate casualties numbered only 155.) The rout prompted the establishment of a Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, which would grow into an influential investigative body of Congress.

On October 25, at Greenpoint, New York, the keel was laid for a 987-ton ironclad turret gunboat called the Monitor. “The most gigantic naval preparations have been made by the enemy,” Confederate war clerk John Beauchamp Jones confided to his diary, “and they must strike many blows on the coast this fall and winter.”

On the 31st, Pvt. David Day of the 25th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry wrote that his regiment was heading to “the Sunny South.” He knew, of course, that no vacation lay in store. “Probably some of us have seen our friends for the last time on earth, and bade them the last good-bye,” he added. “But we will go forward to duty, trusting in God, and hoping for the best.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)