Score One for Roosevelt

“Football is on trial,” President Theodore Roosevelt declared in 1905. So he launched the effort that saved the game

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110920125013VonGammon-500x244.jpg)

On an apple-crisp fall day in 1897, an 18-year-old University of Georgia fullback named Richard Von Gammon launched himself into Virginia’s oncoming rush and vanished beneath a heap of players. He was the only one who didn’t get up. Lying flat on the field at Atlanta’s Brisbane Park, he began to vomit as his teammates circled around him. His skin grew pale and translucent as parchment. One witness recalled that he “raised his eyes in mute appeal, his lips quavered, but he could not speak.” The team doctor plunged a needle full of morphine into Von Gammon’s chest and then realized the blood was coming from the boy’s head; he had suffered a skull fracture and concussion. His teammates placed him in a horse-drawn carriage headed for Grady Hospital, where he died overnight. His only headgear had been a thick thatch of dark hair.

Fatalities are still a hazard of football—the most recent example being the death of Frostburg State University fullback Derek Sheely after a practice this past August—but they are much rarer today. The tragedy that befell Richard Von Gammon at the turn of the 20th century helped galvanize a national controversy about the very nature of the sport: Was football a proper pastime? Or, as critics alleged, was it as violent and deadly as the gladiatorial combat of ancient Rome? The debate raged among Ivy League university presidents, Progressive Era reformers, muckraking journalists and politicians. Ultimately, President Theodore Roosevelt, a passionate advocate of the game, brokered an effort to rewrite its rules.

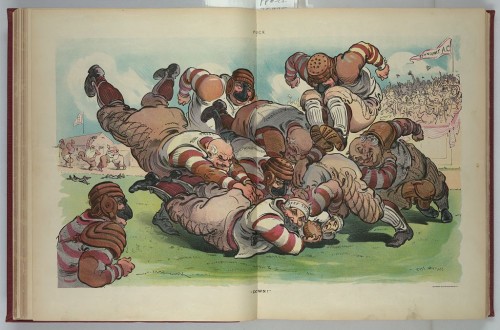

In its earliest days, through the 1870s, football bore a closer resemblance to rugby than to the sport we watch today. There was no passing. Kicking the ball was the most efficient way to score, and blocking was illegal. Players clashed without the benefit of any protective gear, and frequent pileups allowed them to throw punches and jab eyes—melees that only bolstered the spectators’ enthusiasm. The line of scrimmage was introduced in the early 1880s, but that didn’t diminish the violence. “They saw real fighting,” read one account of the 1884 Princeton-Yale game, “savage blows that drew blood, and falls that seemed as if they must crack all the bones and drive the life from those who sustained them.” As players devised new strategies, including the “flying wedge”—a play in which the offense tried to spear its way downfield, surrounding the ballcarrier in a V formation—the brutality only increased. In 1894, when Yale battled Harvard, the carnage included a broken nose, a snapped collarbone, an eye gouged badly enough that it spurted blood, and a collision that put one player into a coma.

Football’s various critics began to coalesce. E.L. Godkin, the editor of the Nation, opined that the Harvard-Yale contest was as deadly as the Union assault at Cold Harbor during the Civil War. The New York Times, once a booster of the sport, now fretted about its “mayhem and homicide” and ran an editorial headlined “Two Curable Evils”—the first being the lynching of African-Americans, the second being football. Harvard president Charles W. Eliot argued that if football continued its “habitual disregard of the safety of opponents,” it should be abolished. After the high-profile death of Richard Von Gammon, Eliot amplified his attacks, dismissing Harvard’s intercollegiate athletics as “unintelligent.” He also took aim at a fellow Harvard man, Theodore Roosevelt, then the assistant secretary of the Navy, condemning his “doctrine of Jingoism, this chip-on-the-shoulder attitude of a ruffian and a bully”—referring not only to Roosevelt’s ideas on foreign policy, but also to his advocacy of football.

Roosevelt had been a sickly child, afflicted with severe asthma, and found that rigorous physical activity alleviated both his symptoms and sense of helplessness. He logged long hours at Wood’s Gymnasium in New York City and took boxing lessons. For a time he lived out West and became a skilled and avid hunter, and bristled at any suggestion that he was a blue-blooded dandy. One night in 1884 or ’85, at a bar near the border of what are now Montana and North Dakota, Roosevelt heard a taunt from a fellow patron: “Four eyes is going to treat.” The man approached, his hand clenching his gun, and repeated his order. Roosevelt stood and said, “Well, if I’ve got to, I’ve got to.” He hit the bully quick and hard on the jaw, causing him to fall and strike the bar with his head. While the man lay unconscious, Roosevelt took his guns.

Roosevelt was too short and slight to play football, but he had developed an affinity for the game after he entered Harvard in 1876. It required, he wrote, “the greatest exercise of fine moral qualities, such as resolution, courage, endurance, and capacity to hold one’s own and stand up under punishment.” He would recruit former football players to serve as his “Rough Riders” during the Spanish-American War. As the crusade against football gained momentum, Roosevelt penned an impassioned defense of the sport. “The sports especially dear to a vigorous and manly nation are always those in which there is a certain slight element of risk,” he wrote in Harper’s Weekly in 1893. “It is mere unmanly folly to try to do away with the sport because the risk exists.”

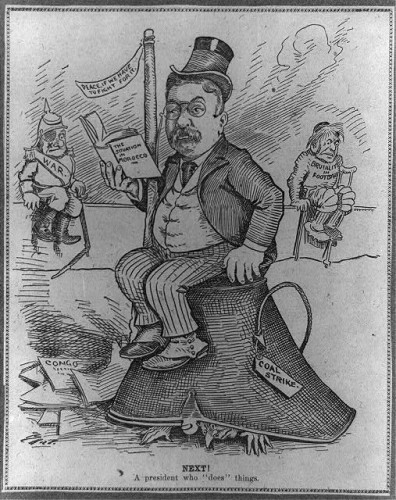

"Brutality in Football" was seen as one of a few high-ranking items on Roosevelt's presidential to-do list. Drawing: the Library of Congress.

But as football-related casualties increased, even Roosevelt recognized that the game would have to be changed in order to be preserved. In 1905, the fourth year of his presidency, 18 players died and 159 suffered severe injuries. During that season one Princeton alumnus tallied, among other wounds, four concussions, three “kicks in the head,” seven broken collarbones, three grave spinal injuries, five serious internal injuries, three broken arms, four dislocated shoulders, four broken noses, three broken shoulder blades, three broken jaws, two eyes “gouged out,” one player bitten and another knocked unconscious three times in the same game, one breastbone fractured, one ruptured intestine and one player “dazed.”

On October 9, Roosevelt convened a football summit at the White House. Attendees included Secretary of State Elihu Root, as well as athletic directors and coaches from Harvard, Yale and Princeton. “Football is on trial,” Roosevelt declared. “Because I believe in the game, I want to do all I can to save it. And so I have called you all down here to see whether you won’t all agree to abide by both the letter and spirit of the rules, for that will help.” The coaches eventually acquiesced. In March 1906, 62 institutions became charter members of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (to be renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association in 1910). Within a few weeks the organization began overhauling the rules of the sport, jump-starting football’s evolution toward its modern form. In time the rule-writers increased the yards necessary for a first down from five to ten, created a neutral zone at the line of scrimmage, limited the number of players who could line up in the backfield to five, prohibited hurdling, established a penalty system and, most important, allowed the forward pass, which lessened the risk of violent pileups.

Roosevelt died in 1919, far too early to see football become America’s most popular sport, but no one involved in the 1905 negotiations forgot what he did for the game. “Except for this chain of events there might now be no such thing as American football as we know it,” wrote William Reid, who coached Harvard during that turbulent time. “You asked me whether President Theodore Roosevelt helped save the game. I can tell you that he did.”

Sources

Books: The Big Scrum, by John J. Miller (HarperCollins 2011), is a fascinating and thorough account of football’s history and Theodore Roosevelt’s role in its evolution.

Articles: “Hears Football Men.” The Washington Post, October 10, 1905; “Deaths From Football Playing.” The Washington Post, October 15, 1905; “Publishes List of Football Injuries.” San Francisco Chronicle, October 13, 1905; “From Gridiron to the Grave.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 31, 1897; “Football Safe and Sane.” The Independent, November 22, 1906. “Pledge to the President.” The Washington Post, October 12, 1905. “Reform Now Sure.” The Boston Daily Globe, November 27, 1905.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)