Annihilate the enemy. That was Adolf Hitler’s standing order to his elite Waffen-SS as the Wehrmacht sought to break the Allies’ tightening grip in late 1944 by crashing through enemy lines in an audacious counteroffensive that would become known as the Battle of the Bulge. The Führer’s edict was enforced in the ice-encrusted fields outside the Belgian city of Malmedy. On the afternoon of December 17, a battle group of the armored First SS Panzer Division ambushed a band of lightly armed U.S. troops. The overwhelmed American GIs’ only option was to raise white flags.

The Nazis accepted their surrender and assembled the American prisoners. Most, they mowed down with machine guns. They used their rifle butts to crush the skulls of others. Those seeking refuge in a café were burned alive or shot. Earlier that day, outside the nearby town of Honsfeld, an American corporal named Johnnie Stegle was randomly selected from a line of captives by an SS soldier who summoned his best English to yell, “Hey, you!” Then he raised a revolver to Stegle’s forehead, killing him instantly. By day’s end, the toll exceeded 150, with 84 murdered at the deadliest of those encounters: the ill-famed Malmedy Massacre.

The stories of those murdered prisoners of war might never have been told, but 50 Americans played dead or overcame their wounds and later recounted the fate of their executed compatriots. Once the fighting was done, the Americans tracked down 75 of the culprits, from generals to rank-and-file German soldiers. Their trial in the spring and summer of 1946, held in the former concentration camp in Dachau, Germany, was among the most intensely followed of the era. The charges included 12 alleged war crimes committed in the general area of Malmedy over the course of a month, resulting in the deaths of 350 unarmed American POWs and 100 Belgian civilians. In July 1946, all but one of the defendants was pronounced guilty, with 43 condemned to death and 22 to life in prison.

The Allies saw Malmedy as a metaphor for Nazi heinousness and American justice. The frozen corpses of slaughtered POWs had been retrieved and carefully autopsied. Intrepid U.S. investigators gathered evidence and conducted in-depth interviews of survivors from both sides. Military prosecutors laid out a vivid portrait not just of this act of barbarity, but of the modus operandi of the SS, the most savage of Hitler’s war-makers.

An alternative telling of the story arose during and after the proceedings, however, that made it the most controversial war-crimes trial in U.S. history. The new version of the incident flipped the script, casting as malefactors the Army investigators, prosecution team and military tribunal. In this story, American interrogators cruelly tortured the German defendants—they were said to have kicked their testicles and wedged burning matches under their fingernails—and the German confessions were coerced. The United States was out for vengeance, this theory held, which shouldn’t have been surprising given that some of the investigators were Jews. Yes, war was brutal, but any atrocities committed that December day in 1944 should be laid at the feet of the Nazi generals who issued the orders, not the troops who followed them. Yes, America had won the war, and it was imposing a classic victor’s justice. The primary advocates of this alternative narrative were the chief defense attorney, the convicted perpetrators and their ex-Nazi supporters, some U.S. peace activists and, most surprising, the junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy.

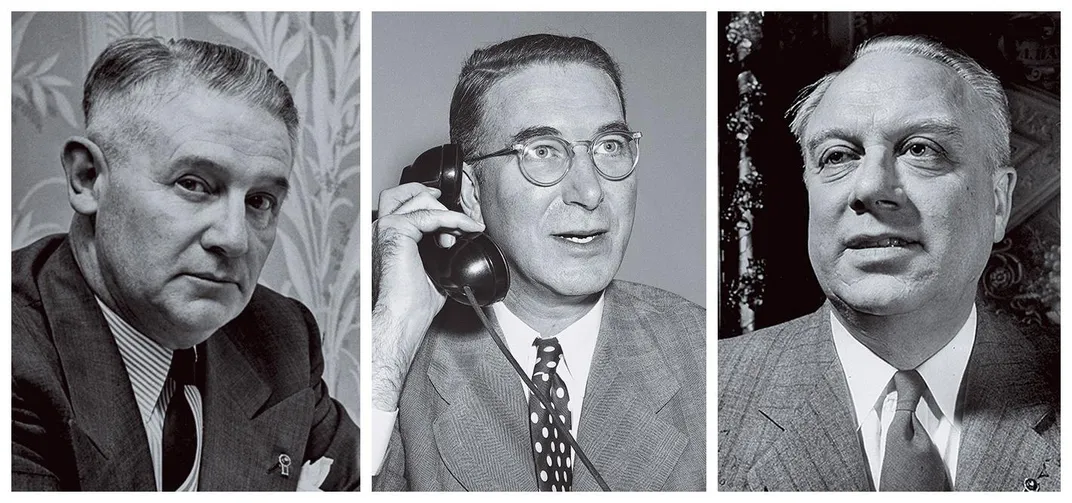

Three years after the verdicts, the Army appointed a commission to sort out the conflicting interpretations of the Malmedy prosecutions. That probe spawned more lurid news accounts of alleged coercion of testimony and mistreatment of the German inmates, which led the Army to name yet another review panel. With political pressure building, in March 1949 the Senate convened a special investigatory subcommittee made up of Raymond Baldwin of Connecticut, Estes Kefauver of Tennessee and Lester Hunt of Wyoming. McCarthy, who’d been intensely interested from the start, was granted special authorization by the panel to sit in as an observer.

At the time, McCarthy was less than halfway through his first term in the Senate, and he hadn’t yet launched the reckless crusade against alleged Communists that would turn his name into an “ism.” Relegated to the status of a backbencher after Democrats took control of the Senate in 1949, McCarthy was thirsting for a cause that would let him claim the spotlight. The cause that this ex-Marine and uber-patriot picked—as an apologist for the Nazi perpetrators of the bloodiest slaughter of American soldiers during World War II—would, more than anything he had done previously, define him for his fellow senators and anybody else paying close attention. But so few were paying him heed that no alarms were sounded, and in short order his Malmedy trickery was overshadowed by his campaign against those he branded as un-American, an irony that lends special meaning to this forgotten chapter in the making of Joe McCarthy.

* * *

McCarthy’s obsession with Malmedy has been a mystery to historians. Why would he jeopardize the war-hero reputation that had helped him prevail in his bid for the U.S. Senate? Why focus on an episode most people were eager to forget? Clues about his behavior reside in the personal and professional papers the senator’s widow left to Marquette University, his alma mater, 60 years ago, but which had been under lock and key until his family made them available exclusively to this author. Those records, along with others provided by the American military, offer insights into the complex machinations that drove this senator who recognized no restraints and would do anything to win.

His fascination grew out of a seemingly genuine fear that Germans were being mistreated in the wake of the war. It was an unusual posture for a returning GI, although he’d fought the Japanese as a Marine in the South Pacific, never the Nazis. During his 1946 Senate campaign, he’d charged that more than 100,000 German POWs were dying from “ill treatment and lack of food.” And while it was a step too far for many to think that the U.S. armed services might take revenge on their former enemy, it wasn’t for the senator who would be dubbed “Low Blow Joe.” In his wartime diary, which was among the papers I reviewed, he made clear how little use he had for America’s military brass, whom he called “mental midgets.” McCarthy himself never explained why he got entangled in the Malmedy affair, but his wife, Jean, seemed to speak for him when she insisted that his intent throughout was noble. “Joe felt this was a brand of ‘justice’ that could be turned against us in the future,” she wrote in an unpublished memoir buried in the senator’s files at Marquette University. “This was not a popular opinion to hold.” It was his willingness to stake out an unpopular stand like that, Jean added, that made her fall in love with Joe.

Those same files show that, while his opponents and some journalists had dismissed McCarthy’s claims that he was a tail gunner and bona fide hero during his World War II service, he was both, albeit with caveats. Officially, he served as a land-based intelligence officer, but he repeatedly volunteered for combat flights, some fraught with peril. And while he was an unabashed self-promoter, exaggerating details of his missions and the number of them he flew, his documents and Marine Corps records suggest that he deserved each of his 11 medals, commendations and ribbons. All of which makes his siding with the Malmedy murderers even more perplexing.

With McCarthy, however, nothing was ever simple, and his political ambitions always factored in. He was himself one-quarter German, and people with Germanic roots made up majorities in 41 of 72 Wisconsin counties. While it’s unfair to assume those constituents supported those who carried out the massacre, many German-Americans nonetheless believed that not all German soldiers should be tainted as butchers. John Riedl, managing editor of the Appleton Post-Crescent, told friends that he was the one who’d talked McCarthy into attacking the Malmedy prosecutors, convincing him that German-American farmers would thank him. But McCarthy, who came from that farm country, didn’t need coaxing.

A more troubling theory popular with his critics holds that McCarthy’s actions regarding Malmedy were driven by anti-Semitism. As evidence, they pointed to his casual and frequent use of anti-Jewish slurs, which even his closest friends acknowledged to biographers. Les Chudakoff, his lawyer, was “a Hebe.” A Jewish businessman McCarthy suspected of cheating him was “a little sheeny.” And, according to Army General Counsel John Adams, the senator repeatedly referred to a Jewish staffer he disdained as a “no good, just a miserable little Jew.” Then there was the support McCarthy got from notorious Jew-haters like radio commentator Upton Close, and the backing McCarthy gave to fascist activist William Dudley Pelley. “There was scarcely a professional American anti-Semite who had not publicly endorsed the senator,” said Arnold Forster, who followed the situation in real time as the general counsel at the Anti-Defamation League.

For years, friends recounted how McCarthy would pull out his copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, saying, “That’s the way to do it.” But, they were quick to add, that was just Joe being provocative. Now, the Malmedy hearings suggested a deeper-seated anti-Semitism. Why else would this one senator among 96 crusade to save the worst of Hitler’s shock troopers? Why single out Jewish investigators who, McCarthy claimed during the hearings, “intensely hate the German people as a race” and had formed what amounted to a “vengeance team?”

The view that McCarthy’s reaction to the Malmedy prosecution was partly rooted in anti-Semitism was reinforced the following year, when he led a smear campaign against Anna Rosenberg, a Hungarian-born Jew and WWII heroine who was tapped by Defense Secretary George Marshall to raise troops for the Korean War. McCarthy’s allies included the Holocaust-denying Ku Klux Klansman Wesley Swift, who said the nominee was not merely a “Jewess” but “an alien from Budapest with Socialistic ideas.” In the end, Republicans on the Armed Services Committee joined Democrats in unanimously approving the nomination, and McCarthy himself was forced to do an about-face, not just ending his bid to defeat Rosenberg but voting to confirm her.

McCarthy again faced accusations of an anti-Jewish fixation when, in 1953, he went after alleged Communist subversives at the Army base at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Of 45 civilians suspended by the Army as possible security risks, 41 were Jews, whereas only 25 percent of the base’s overall civilian workforce was Jewish, according to the Anti-Defamation League. McCarthy claimed that he was following the military’s lead in picking his targets, but several witnesses who appeared at his hearings said the senator was singling out Jews.

The senator’s defenders, however, pointed out that he had Jewish friends and Jewish staffers (most notoriously the pugnacious lawyer Roy Cohn), and that he advocated for Israel while decrying Soviet suppression of Jews. Notorious xenophobe and onetime presidential candidate Agnes Waters went so far as to accuse the senator of being a “crypto Jew,” claiming that “McCarthy” was a pseudonym used to disguise a Jewish surname. His friend Urban Van Susteren called McCarthy out when he thought he was wrong, including when he used the slur “Hebe,” but he insisted that McCarthy found anti-Semitism personally abhorrent.

Van Susteren, in my view, overstated the case. Anti-Semitism did factor into McCarthy’s attacks against the Malmedy prosecutors and his defense of the perpetrators, and so did opportunism. The incident, after all, put him on the center stage he coveted, and gained him favor with the political right that was becoming his base of support. The Wisconsin senator didn’t have it in for Jews specifically any more than he did gays, “pinkos,” East Coast intellectuals, Wall Street mavens, Washington insiders, political journalists, or anyone else he disdained and could vilify to score political points. Scapegoating is part of every bully’s playbook, and it’s why McCarthy became the archetype for demagogues who came after him. It was a game. He would savage an opponent in the afternoon and that evening invite him or her for a drink. He presumed his targets knew the way sport worked.

* * *

Whatever combination of incentives drew McCarthy to the cause of the Malmedy killers, once he got involved, he convinced himself that what he was saying was not just right, but righteous. He was standing up not for Nazi assassins but against a “shameful episode” of retributive justice by the U.S. military. The fuel for his attacks came in letters air-mailed or hand-delivered from a parish priest, an ex-Nazi lawyer, and others in the American zone of a divided Germany, along with friends like Milwaukee industrialist Walter Harnischfeger. They laid out allegations of American abuse and insisted the prisoners get clemency. McCarthy bought the claims, which also were sent to, and generally ignored by, other members of Congress. He championed proposed pardons. And once the Senate investigation got underway in the spring of 1949, he dominated the proceedings that he was supposed to be merely observing. McCarthy’s name turned up in the transcripts of the hearings 2,683 times, compared with 3,143 for Baldwin, 578 for Hunt and 184 for Kefauver.

While he preferred to be the one asking questions, he was himself subjected to grilling by military lawyers, investigators and subcommittee senators. How could he be so sure about The Progressive magazine’s allegations that Nazi prisoners had been abused when the article’s bylined author later said that it was in fact written by an antiwar activist, and that much of it was exaggerated? What about McCarthy’s other “sources,” who, McCarthy said, had witnessed beatings but who later, on the stand, recanted their tales of tortured prisoners and biased investigators? It quickly became clear how ill-prepared the Wisconsin senator was, in contrast to the thoughtful experts he was challenging. His case in tatters, McCarthy turned to what would become his default tactic whenever he was cornered: His adversaries were two-faced, he raged, and a lie detector could prove it.

“I think you are lying,” he told Lt. William Perl, the chief Malmedy investigator, a European-born Jew and a staunch defender of the Army’s approach. “I do not think you can fool the lie detector. You may be able to fool us.” Perl, a psychologist as well as an attorney who’d helped smuggle 40,000 Jewish refugees to Palestine before fleeing Vienna for the United States in 1940, made clear he wasn’t intimidated by McCarthy. He agreed to subject himself to the polygraph but wondered sardonically, “Why [have] a trial at all? Get the guys, and put the lie detector on them. ‘Did you kill this man?’ The lie detector says ‘Yes.’ Go to the scaffold. If it says, ‘No’—back to Bavaria.”

McCarthy knew the subcommittee would decline his lie-detector demand, because members rightly doubted the machine’s accuracy and because fairness would dictate giving the test not just to the interrogators but to the SS inmates, who were unlikely to accept. His polygraph bluff gave McCarthy an excuse to storm out of the proceedings. “I feel that the investigation has degenerated to such a shameful farce that I can no longer take part therein and I am today requesting the expenditures subcommittee chairman to relieve me of the duty to continue,” he told Baldwin and the others. The truth is that neither the subcommittee nor anyone else in Congress had pushed him to sit in on the Malmedy proceedings or was fazed that he was quitting. But the always-eager press did care, and so, even before McCarthy addressed his fellow senators, he was ready with a news release blasting his colleagues. “I accuse the subcommittee of being afraid of the facts,” he said. “I accuse it of attempting to whitewash a shameful episode in the history of our glorious armed forces.”

Baldwin, a former three-term governor of Connecticut who had been talked by colleagues into serving as chairman, responded with characteristic understatement: “The chairman regrets that the junior Senator from Wisconsin, Mr. McCarthy, has lost his temper and with it, the sound impartial judgment which should be exercised in this matter.”

McCarthy was irrepressible. He said America’s treatment of the Malmedy prisoners made it “guilty of adopting many of the very same tactics of which we accuse Hitler and Stalin.” He condemned the Army for “brutalitarianism,” and he challenged the integrity of subcommittee members. The Armed Services Committee took an unorthodox action of its own, unanimously approving a vote of confidence in Baldwin. We “take this unusual step,” they explained, “because of the most unusual, unfair, and utterly undeserved comments” made by Senator McCarthy. Signing the measure were such lions of the chamber as Lyndon Johnson, Harry F. Byrd, William F. Knowland and Styles Bridges, who would become one of McCarthy’s staunchest allies in the 1950s. Everyone but McCarthy got the point.

The subcommittee, meanwhile, pursued its mission to determine whether the Army had been fair in probing the massacre at Malmedy. The three senators interviewed 108 witnesses, from the SS perpetrators and their defense team to investigators, prosecutors, judges, religious leaders and others on all sides. Everyone McCarthy asked the panel to talk to it did, and it extended him the unusual courtesy of letting a non-member cross-examine witnesses. Prisoners were checked out by Public Health Service doctors and dentists, looking for signs of abuse.

In its final report, issued in October 1949, the subcommittee criticized the military for using mock trials with a fraction of the prisoners to elicit confessions or soften up suspects (“a grave mistake”), and for the official use of mass military trials that lumped officers with subordinates (“they should be indicted and tried separately”). But it was even more plain-spoken in its primary conclusions: There was little if any beating, kicking or other brutalization of prisoners. They’d been given plenty of food, water and medical attention. Their trials were fair. And, most important in explaining why such charges had been raised, then re-raised, the subcommittee said they sprung from a coordinated campaign of misinformation involving ex-Nazis and possibly Communists in Germany, along with an “extreme” pacifist organization in America, the National Council for the Prevention of War.

That Senate verdict notwithstanding, the military was already moving to defuse the controversies in West Germany and the United States. Bowing to popular pressure, some of the death sentences of the SS murderers had been commuted, and the rest would be. By the late 1950s all the former SS prisoners would be freed. One of the last to walk out of prison, in December 1956, was Joachim Peiper, commander and namesake of the SS unit that mowed down the surrendering GIs in the fields near Malmedy.

* * *

The narrative that America had reason to apologize for its handling of those murderers has persisted for three-quarters of a century not only in history texts but also in online platforms, thanks in part to the legitimacy conferred on it by the most outspoken member of the U.S. Senate. Some McCarthy defenders viewed Malmedy as a precursor to U.S. mistreatment of Iraq War detainees half a century later, and saw the Abu Ghraib whistle-blowers as following in McCarthy’s footsteps. But in his recent book, The Malmedy Massacre, which draws on newly declassified documents, and in my correspondence with him, European history scholar Steven Remy sets things straight. “Both willfully clueless and supremely self-confident, McCarthy impeded but did not derail a truly fair and balanced investigation of the Malmedy affair,” Remy told me in an email. Col. Burton Ellis, the chief Malmedy prosecutor and one of McCarthy’s favorite targets, remained incensed at McCarthy’s distortions when he looked back three decades after the hearings: “It beats the hell out of me why everyone tries so hard to show that the prosecution[s] were insidious, underhanded, unethical, immoral and God knows what monsters, that unfairly convicted a group of whiskerless Sunday school boys.”

McCarthy’s casting of the SS prisoners as the aggrieved, and U.S. military prosecutors as transgressors, had practical consequences. Germany’s left-wing press and the Anglo-American right echoed his rhetoric and used it to inflame readers against U.S. military occupiers. Virgil P. Lary Jr., a U.S. Army lieutenant who escaped the Malmedy massacre by pretending to be dead, told reporters in 1951, “I have seen persons bent on murdering me, persons who murdered my companions, defended by a United States senator....I charge that this action of Senator McCarthy’s became the basis for the Communist propaganda in western Germany, designed to discredit the American armed forces and American justice.”

But Malmedy was a warm-up act. Even as McCarthy muddied the incident’s historical record, he telegraphed the kind of scorched-earth senator he would become. He embraced conspiracy theories and opted not to vet propaganda when it served his political purposes. He dished to the press, instinctively grasping its hunger for inflammatory phraseology like “whitewash” (it appeared nine times under his name in the hearing transcripts) and epithets like “moron” or “moronic,” and he had a knack for generating headlines by challenging his opponents to submit to a “lie detector” (which appeared 25 times). He intuited that deploying small-seeming fibs might not only go unchallenged but would tilt a narrative in his favor, for instance by referring to the SS slaughterers as younger than they were and therefore more deserving of sympathy. While the youngest were 18, McCarthy went from referring to them as “18 and 19” to “a 15- or 16- or 17- or 18-year old boy.”

Discrediting an accusation might send him into momentary retreat, but he’d soon resurrect the indictment and claim vindication when there was none. His favorite targets were Democrats, but Baldwin learned that Republicans weren’t immune, and that McCarthy didn’t care about the Senate’s rules of decorum. The Connecticut lawmaker had decided before the Malmedy hearings to resign his Senate seat, but the verbal abuse he suffered at McCarthy’s hands made him happier to go, and convinced his biographer that he was “the first victim of ‘McCarthyism.’”

Editor's note: An earlier version of this piece mentioned that McCarthy was one senator among 100. In fact, there were only 96 senators at the time.

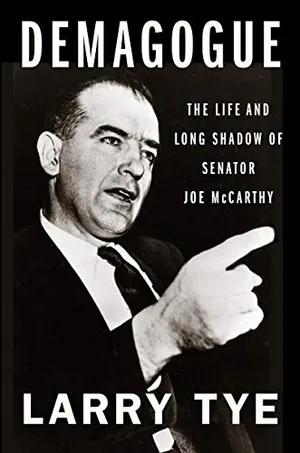

Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy

The definitive biography of one of the most dangerous demagogues in American history, based on first-ever review of his personal and professional papers, medical and military records and recently unsealed transcripts of his closed-door Congressional hearings.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/fc/4ffc718f-017c-4067-933c-311c1a772629/mobile_opener_-_julaug2020_d09_josephmccarthy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/18/241808b6-dd51-415b-a426-2815085f7707/opener-julaug2020_d09_josephmccarthy.jpg)