A Sensational Murder Case That Ended in a Wrongful Conviction

The role of famed social reformer Jacob Riis in overturning the verdict prefigured today’s calls for restorative justice

:focal(396x259:397x260)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/24/c22480df-067b-41eb-962a-9d50e9349c5b/untitled-1.jpg)

It seemed New York City had its own Jack the Ripper. In April 1891, the mutilated body of Carrie Brown, a former self-styled actor, turned up in what the New York Times called a “squalid” lodging house of “unsavory reputation.” The fame that eluded her in life found her now, with the newspapers eagerly serving up lurid details, factual or not. Brown supposedly once recited a scene from Romeo and Juliet atop a saloon table. Her penchant for quoting the bard, coupled with her age—she was 60—earned her the nickname “Old Shakespeare.”

She also, it appears, had worked as a prostitute, which along with the heinousness of the crime, including an X carved into her skin, fueled comparisons to the depredations of Jack the Ripper, who had begun terrorizing London three years before and would murder between 5 and 12 women. Jack the Ripper was so widely notorious even then that Thomas Byrnes, chief of detectives in the New York City Police Department, had boasted they would catch the London serial killer within 36 hours. As if on cue, his men arrested a suspect in Brown’s murder in 32 hours. He was a middle-aged Algerian sailor named Ameer Ben Ali.

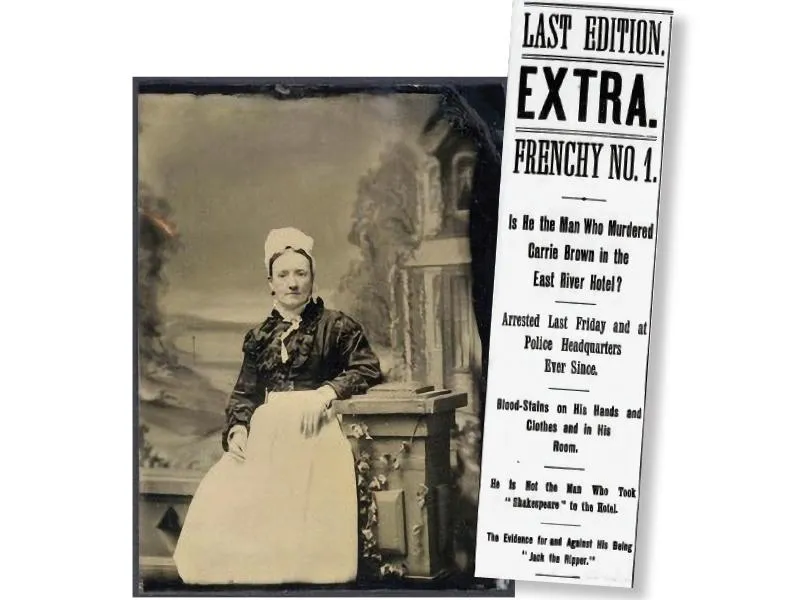

The closely watched trial in the Court of General Sessions lasted one week. The evidence against Ben Ali, known to many reporters as Frenchy, was thin and contradictory. He had previously admitted to larceny—he’d stolen a watch—and had been cited for vagrancy, and he did stay at the hotel where Brown was killed on the night in question. Witnesses testified that they had seen a trail of blood leading from Brown’s hotel room to Ben Ali’s. The hotel proprietors said Brown checked in with a man in his 30s of foreign descent, but they also said he was light-haired and possibly German.

Ben Ali had dark hair, and during the trial he denied knowing the victim. Speaking mainly in Arabic through an interpreter, he wept and swore his innocence before Allah. The jury deliberated for two hours. “‘Frenchy’ Found Guilty,” announced a headline in the Times.

Over the years Ben Ali appealed the conviction and applied for pardons, without success, and the whole sordid matter would have been forgotten if not for the dogged skepticism of several men, in particular the photographer, reporter and social reformer Jacob Riis.

Known for detailing the poverty of New York City’s slums in words and images, Riis was considered revolutionary for the compassion and dignity he showed his subjects in his 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives, today recognized as a classic. Its stark photographs documented the dangerous and degrading conditions of poor immigrant neighborhoods. Riis was familiar with these neighborhoods not just from his work as a police reporter for the Tribune and Evening Sun but also from his own experience in his early 20s as a struggling Danish immigrant.

Riis was working for the Evening Sun the April night Brown was murdered, and he visited the scene of the crime. He did not testify at the trial, but he would later insist that a central part of the case against Ben Ali was false: There was no blood trail. In an affidavit submitted to the court in 1901, Riis wrote that “to the best of my knowledge and belief there were no blood spots on the floor of the hall or in and around the room occupied by ‘Frenchy’ on the night of the murder.” That account would apparently be substantiated by Charles Edward Russell, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for the New York Herald. In a 1931 article in Detective Magazine, he recalled arriving on the scene of the Brown murder with another reporter, most likely Riis, and seeing no blood between the rooms occupied by Brown and Ben Ali.

Other exculpatory evidence surfaced only after the trial. Russell also recalled that the Herald received a letter from a seaman who said a shipmate of his was onshore the night of the murder and returned to the ship with bloody clothes. George Damon, a wealthy New York businessman, wrote in a 1901 affidavit that one of his servants had gone missing the night of the crime and had left behind bloody clothing and a key to the hotel before fleeing. Damon did not come forward at the time of the trial.

In the years after his confinement, at Sing Sing prison, the stories about Ben Ali that appeared in the newspapers were mostly favorable, according to George Dekle, a former Florida prosecutor whose book about the Ben Ali case comes out in August. The Times, reminding readers in 1897 that the evidence against Ben Ali was circumstantial, said the French ambassador and the consul general were calling for the man’s release. Meanwhile, Ben Ali reportedly grew despondent and in 1893 was moved to the New York State Asylum for Insane Criminals at Matteawan. Finally, in 1902, New York Gov. Benjamin Odell Jr. commuted Ali’s sentence, and Ali was taken to New York City. He was said to return to Algeria or France. In Odell’s papers, he cites Riis’ affidavit as influencing his decision.

Contemporary accounts point to other factors in the governor’s decision. Daniel Czitrom, co-author of the 2008 book Rediscovering Jacob Riis, believes that Damon’s affidavit was of primary importance to the governor. For his part, Dekle stresses the influence of French officials. Overall, though, scholars say Riis played a central role in obtaining Ben Ali’s freedom.

Through his books, articles and national lecture tours, Riis continued to draw attention to persistent poverty, especially among new immigrants, and the roles that government, religion and private philanthropy should play in reform. Riis advocated for new housing designs that addressed fire safety, sanitation and overcrowding. He helped establish public parks, promoted early childhood education and worked with health officials to document the spread of diseases. Riis died of heart disease in 1914 at age 65, a pioneer in the use of photography to inspire social reform.

Today’s appetite for restorative justice, especially the freeing of the wrongfully convicted, echoes Riis’ efforts more than a century ago. In 1988, the cause received a boost from The Thin Blue Line, the Errol Morris documentary film about a man mistakenly convicted of murder in Texas. Another impetus came the next year—the use of DNA evidence. Suddenly it was less difficult to prove innocence. Since then, more than 2,780 convictions, 38 percent of them for murder, have been reversed, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, a database run by a consortium of university research centers and law schools. In the 169 years prior to 1989, the registry shows, fewer than 500 convictions were overturned. One of those was unusually significant—that of Ben Ali, believed to be the first U.S. case in which a journalist, none other than Jacob Riis, helped free an imprisoned man.